Gill Davies

1 From Transylvania to London

The critical discussion of Dracula has emphasised the importance of place in structuring the narrative and developing the themes of the novel. Stephen Arata and others have shown how the geography of the novel echoes contemporary fears about global economic competition and builds on racial anxieties, particularly in its opposition of East and West. Dracula is a novel about crossing borders, encountering the alien and driving it back; it is also about dangerous, unrestrained movement and the need for confinement of the threatening ‘other’. In this article, I will concentrate on the way in which the detailed geography of London is deployed to highlight a number of imperial and national anxieties. These anxieties are mapped on to some of the key places in the fin de siecle / modern metropolis. The location map and the four detailed maps at the end of this article show the key movements and locations in the text.

There are references throughout the novel to the four compass points, but especially to east and west. This opposition is a familiar one in the construction of London and it had gathered particular ideological and emotional force by the time Dracula was published. Social explorers, novelists, philanthropists and sociologists had developed this discursive opposition since the 1880s. The West End was the centre of government, wealthy residences and leisure, while the East End was ‘unknown England’, ‘the nether world’, ‘outcast London’, ‘the abyss’. In addition,

West End with its government offices served as a site for imperial spectacle: during her Golden Jubilee in 1887, Queen Victoria… was carted around the major thoroughfares, escorted by an Indian cavalry troop. Meanwhile, another kind of imperial spectacle was staged in the East End. The docks and railway termini of the East End were international entrepots for succeeding waves of immigrants, most recently poor Jews fleeing the pogroms of Eastern Europe.[1]

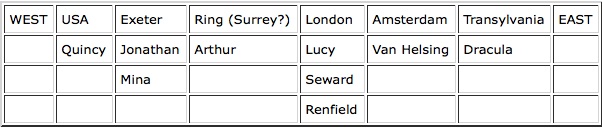

In Dracula, Stoker reiterates this sense of London as both heart and image of the Empire, using its familiar locations to heighten fears of invasion, contamination and disease. Dracula is, of course, from the east, and regularly associated with it. He comes ashore on the east coast at Whitby and takes a house at Purfleet on the Thames at the eastern edge of London. As several critics have shown, Dracula’s association with the East End links him with foreigners, especially Jews from eastern Europe and ‘oriental’ foreigners, as well as with an area associated in the public mind with crime and violence. Indeed, the novel gives us a band of sturdy western Europeans along with the American, Quincy, combining to reject the eastern Other. The broad locations of the novel match the moral authority and destiny of the main characters and can be schematically represented as:

There is a clear spectrum of value, moving from west to east. Jonathan and Mina share a basic innocence and moral superiority with Quincy. Arthur’s family home is the Godalming estate at Ring, presumably south-west of the capital, and he stays in the West End at the Albemarle in Piccadilly when in London. Dracula’s chief antagonist, Van Helsing has to come from the continent, though from a neighbouring and protestant country, since the ‘innocence’ of England is critical to the dramatic exegesis: Van Helsing is a bulwark against Dracula because he has an understanding of the supernatural and vampire lore that is not possible for an Englishman. The extensive movement that we find in the novel (from the provinces, across Europe, from America) is all to and from London, the ‘world city’.[2] London is the heart of the novel, but also of the empire and the nation. Dracula threatens to consume its blood and cut off the circulation of its capital. Although he is linked to the East End and the moral panics associated with it, Dracula is at his most dangerous in the West End.

The concentration on London is contextualised by the opening sections of the novel in which Jonathan Harker travels east across Europe. His account highlights the border between the civilised west and the dangerous orient. (Even his train is one hour late, as civilisation is left behind.) Budapest is seen as the dividing point between east and west: he crosses the Danube into “the traditions of Turkish rule”.[3] Castle Dracula is “in the extreme east of the country, just on the borders of three states” so that Dracula’s liminality is emphasised. In addition, Transylvania is uncharted and Jonathan cannot get “the exact locality of the Castle Dracula as there are no maps of this country as yet to compare with our own Ordnance Survey maps” (10). By contrast, the count makes good use of the modern communications and maps that are the product of the great imperial project. For Victorian readers the lateness of the trains demonstrates the backward and primitive nature of this country – “the further east you go the more unpunctual are the trains” (11). And only a few pages later, Jonathan finds Dracula “lying on the sofa, reading, of all things in the world, an English Bradshaw’s Guide” (34) which will guarantee his easy movement around the country. Also on the table is “an atlas which I found opened naturally at England, as if that map had been much used” (36). The places Dracula has marked in the atlas are very significant: Purfleet, Exeter, and Whitby. In the plot, they are the places where he will live and find his first victims (Lucy at Whitby, Renfield in the asylum next to the house at Purfleet) and the address of his solicitor (Exeter) which is also the town where Mina is working as schoolteacher. It is important that Dracula has already planned these locations, basing himself in London at the centre and spreading his influence out north east and south west. Most of the main characters are brought together by Dracula, in his plot, before they join together to try to defeat him.

Dracula’s desire for economic power is affirmed when he asks Jonathan about legal transactions; how many solicitors he can have for “banking” and “shipping” (43). His will be a business empire, though the goods he will ship initially are boxes of soil plus himself. We are told (45) that he is writing, among others, to Coutts & Co. London, a bank with very rich and important customers, including the royal family — another sign of Dracula’s ambition and his threat to the symbols of national power. The house that Jonathan has found for Dracula is called Carfax. He explains this as deriving from the fact that “the house is four-sided, agreeing with the cardinal points of the compass” (34). This is another reference to mapping and to Dracula’s plans to use the geography of London to conquer it. According to Leonard Wolf, another derivation is not “quatre face” but “carrefour”, a crossroads, “a place where four roads meet”,[4] reinforcing Dracula’s position at the centre and his plan to access each corner of the city.

Soon after, Jonathan finds the Count in his coffin, recently fed, and comments that “This was the being I was helping to transfer to London, where, perhaps for centuries to come, he might, amongst its teeming millions, satiate his lust for blood, and create a new and ever widening circle of semi-demons to batten on the helpless” (67). Of course, this provokes fear for the empire and the race, but the key word here is “transfer”. Dracula himself is represented as goods or money to be transferred legally by this English solicitor to the heart of London, an extended analogy between Dracula and the threat of foreign capital. (Compare Moretti’s very useful discussion of the vampire and capital where he points out that Dracula was published after “twenty long years of recession”.)[5] The novel thus indirectly expresses contemporary concerns about the state of the British economy and competition from abroad. Dracula is the parasite (the speculator, represented so often as a Jew)[6] waiting to benefit from England’s decline.

Then, in the library, Jonathan finds,

. . . a vast number of English books, whole shelves full of them… all relating to England and English life and customs and manners. There were even such books of reference as the London Directory, the ‘Red’ and ‘Blue’ books, Whitaker’s Almanack, the Army and Navy Lists, and . . . the Law List. (30)

The London Directory is a business list; the Red Books listed all the state pensioners from the courts and civil service; the Blue Books were Parliamentary records and reports; Whitaker’s had been since 1868 a directory of information on the British government and social structure; and the Army, Navy and Law lists included the names of officers, qualified solicitors, barristers, judges and so on. What Dracula has accumulated, like a terrorist, is a compendium of the institutions and people involved in all the important areas of British society: business; government; the civil service; the armed forces; the legal system . As Dracula himself says,

Through them I have come to know your great England; … I long to go through the crowded streets of your mighty London, to be in the midst of the whirl and rush of humanity, to share its life, its change, its death and all that make it what it is.’ (31)

Dracula’s interest in the centres of power (financial, political, legal, military) is threatening because of his total knowledge of the institutions and practices of the modern imperial state. Stoker marshals discourses and imagery similar to those we are familiar with now in the ‘war against terrorism’ and the ‘axis of evil’: the threat of shape-changing terrorists from the east, among us and invisible, countered by an Anglo-American alliance. In 1897, it is an image of what Arata calls ‘reverse colonisation’:

In the marauding invasive Other, British culture sees its own imperial practices mirrored back in monstrous forms. Stoker’s Count Dracula … frightens[s] not least because [his] characteristic actions — appropriation and exploitation — uncannily reproduce those of the colonising Englishman.[7]

Dracula’s journey west to the financial capital of the empire is thus a literal transgression of boundaries and a frightening reversal of imperial expansion. Even before the action of the novel moves to London, a powerful set of oppositions and images has been established. Once in London, the spatial meanings are elaborated and intensified.

2 Dracula in London

Various characters converge on London at the same time as the Count. The maps and key (see end) illustrate how important the geography of London is to the representation of Dracula’s growing power. The Hon.Arthur Holmwood stays at the Albemarle Hotel in Piccadilly when he is in town (See Piccadilly map). His and Quincy’s “old pal” (79) Jack Seward is now running the asylum at Purfleet (the west/east axis). Lucy, having written to Mina from an address in Chatham Street, Southwark (presumably a town house near to her father’s business) has returned to Hillingham, the family home in north London, with her mother (the north/south axis). It is near Hampstead Heath, scene of Lucy’s later vampiric outings, and the churchyard where she is buried, at ‘Kingstead'(See Hampstead map). The proximity of the characters to each other, and the ease of modern communication by train and telegraph make it easy for Seward to drop over for an afternoon from Purfleet, or for Van Helsing to come over quickly from the Great Eastern Hotel at Liverpool Street in the east of the city to Hillingham, or from the Berkeley Hotel in Piccadilly in the west (See East End map). Small details, which would be known to many readers, are used to build the sense of Dracula’s monstrous invasion of a familiar space. For example, when Seward arranges to meet Lucy away from her house so as not to worry her ailing mother, they go to Harrods — ‘the Stores’ (138), already a popular place for a respectable woman to be seen.

From early on, Dracula causes disturbance in the west end of the city, where wealth, fashion and leisure are based. First of all, Berserker, a Norwegian wolf in the Zoo in Regents Park, escapes after an encounter with Dracula, then returns with a cut on the head but docile (165). The wolf gets as far as Hillingham where it frightens Lucy and her mother, appearing at the broken window (173-4) (See Regent’s Park and Hampstead maps). This disturbance in the north western reaches of the city is the first indication that Dracula’s influence is spreading from the east. (It is echoed in Lucy’s name, Westenra.) There may be further significance in the introduction of Regent’s Park Zoo. In plot terms, it would have been sufficient to have a wolf escape, but Stoker gives us the lengthy Pall Mall Gazette interview with a keeper (165-171) in his cottage ‘in the enclosure behind the elephant-house.’ Why so much detail? Jonathan Schneer points out that the Zoo was a conscious emblem of Britain’s imperial victories, with animals from every corner of the globe. By the end of the century, ‘visiting the zoo had become a common form of popular recreation. More than half a million people attended annually.'[8] Thus to locate Dracula in the zoo is not only to identify his animalistic and dangerous drives, but also to point up his threat by placing him in relation to a popular imperial signifier.

A more serious disturbance occurs when Dracula begins to “go through the crowded streets of your mighty London” (31) as he had earlier anticipated. Mina and Jonathan have returned to London, after his lengthy period of convalescence in Exeter. Almost immediately Jonathan suffers a relapse after seeing Dracula in Piccadilly (206ff.). This area has become the focal point of the action and represents the high point of Dracula’s power as he achieves his expressed wish to blend into the crowd, to be undetectable as a foreigner (See Piccadilly map). From this point in the novel, Dracula acquires the characteristics of the figure of the flaneur and moves through the city with the powerful freedom associated with that figure. In adopting many of the features of the flaneur, Stoker links Dracula with the quintessential European city type, rather than with the primitive, decadent aristocrat from Transylvania. At the opening of the novel, Dracula is firmly placed as part of ‘old’ Europe, now in terminal decline: associated with peasants, superstition, primitive transport and so on. He is ” a tall old man, clean-shaven save for a long white moustache, and clad in black from head to foot “(25). But once in London he looks quite different: ” a tall, thin man with a beaky nose and black moustache and pointed beard” (207). As well as ‘modernising’ the vampire by associating him with the metropolis, Stoker may be tapping into the prejudices of his readers by linking him to the flaneur. By the end of the nineteenth century, the flaneur’s point of view in the city was firmly established as that of “a man walking, as if alone, in its streets.”[9] The flaneur has a freedom, separateness and protection in the anonymous, complex life of the city and, as a lone figure, is able to penetrate and understand the city because of his detachment. For a largely conservative readership, unable through work and domestic responsibilities to access such freedom, this is a dangerous image. It is also, we may assume, a threatening one. Benjamin stressed the alienation of the flaneur, describing his point of view as,

. . . the gaze of the alienated man. It is the gaze of the flaneur, whose way of life still conceals behind a mitigating nimbus the coming desolation of the big-city dweller. The flaneur still stands on the threshold — of the metropolis, as of the middle class. Neither has him in its power yet. In neither is he at home. He seeks refuge in the crowd.[10]

If we examine the episode in Piccadilly in more detail, it seems clear that this is a pivotal moment in the text. Jonathan and Mina have been strolling, after Mr Hawkins’s funeral, visiting the fashionable and safest parts of the city. They have taken a bus to Hyde Park Corner, visited Rotten Row, and then they walk down Piccadilly. Mina sees Jonathan staring at a man looking at a girl:

I was looking at a very beautiful girl in a big cart-wheel hat, sitting in a victoria outside Giuliano’s, when I felt Jonathan clutch my arm so tight that he hurt me . . . . He was very pale, and his eyes seemed bulging out as, half in terror and half in amazement, he gazed at a tall, thin man … who was also observing the pretty girl. He was looking at her so hard that he did not see either of us, and so I had a good view of him. His face was not a good face; it was hard, and cruel, and sensual . . . . He kept staring; a man came out of the shop with a small parcel, and gave it to the lady, who then drove off. The dark man kept his eyes fixed on her, and when the carriage moved up Piccadilly he followed in the same direction, and hailed a hansom. (206-8)

Dracula demonstrates the flaneur’s freedom to stare, and to follow. He is, in a sense, ‘above’ the small preoccupations of urban life, shopping and so forth. He is directly contrasted with Jonathan whose gaze is powerless and who nearly faints and has to go and sit down in Green Park where he falls into a feminine sleep. Dracula’s movement through London, having access to “the helpless” and in particular to beautiful young women, suggests that the growth of the metropolis, its huge gathering of people, and the introduction of greater freedom for women, only makes the work of evil, pollution and vice easier. He is very far west now and operating in the fashionable heart of London. Piccadilly, Rotten Row and Green Park are traditional locations for the rich, near to the home of the Royal Family, and the centre of Government. In addition, as Walkowitz points out, by this time,

the West End of Mayfair and St James had undergone considerable renovation; from a wealthy residential area it had been transformed and diversified into the bureaucratic center of empire, the hub of communications, transportation, commercial display, entertainment and finance. In the process, a modern landscape had been constructed – of office buildings, shops, department stores, museums, opera, concert halls, music halls, restaurants and hotels – to service not only the traditional rich of Mayfair but a new middle class of civil servants and clerks living in such areas as Bayswater and the nearby suburbs.[11]

These civil servants and clerks, reading Dracula, would get a particular frisson from their awareness of the significance of this location. The flaneur is, of course, specifically a bohemian or upper class figure; a man with leisure and income and as such is quite threatening to the bourgeois work ethic and the ideology of Stoker’s wage-earning readers. Untrammelled by family and responsibilities, he is suspiciously ‘free’. Taken along with Dracula’s foreignness (not to mention his monstrosity), this makes him a troubling figure for a lower middle and middle class readership. In a later note, Benjamin refers to the “case in which the flaneur completely distances himself from the type of the philosophical promenader, and takes on the features of the werewolf restlessly roaming a social wilderness”.[12] This insight is a fascinating link with the figure of the vampire, not very different from the werewolf. And it fits Dracula very well when we remember his animal teeth and the predatory and animalistic way in which he looks at the woman. (He also of course has an affinity with Berserker, the wolf in the Zoo.)

The next major shock in the novel is Lucy’s becoming a predator on children. London is beginning to be encircled by Dracula’s creations and familiars: the wolf in the west, Renfield in the east, and now Lucy in the north (Hampstead Heath (213ff)). This is reinforced by the pattern of distribution of Dracula’s fifty boxes of soil. At the chapel in Carfax, van Helsing and company find only twenty nine boxes left (300). Where are the twenty one boxes that were taken away from Carfax by the carters who live in the east and south of the city (Snelling in Bethnal Green, Smollett in Walworth)? It becomes clear that they are meant to encircle London. As Harker says,

If then the Count meant to scatter these ghastly refuges of his over London, these places were chosen as the first of delivery, so that he might later distribute more fully. The systematic manner in which this was done made me think that he could not mean to confine himself to two sides of London. He was now fixed on the far east of the northern shore, on the east of the southern shore, and on the south. The north and west were surely never meant to be left out of his diabolical scheme — let alone the City itself and the very heart of fashionable London in the south-west and west. (311)

And so it turns out: he discovers nine boxes have been taken to a house in Piccadilly. If Piccadilly is the “very heart of fashionable London”, now only the City, the north and the west remain to be colonised and that is already being accomplished. Is there any significance beyond the broad compass points of the places that Stoker chooses for Dracula’s imperial conquest? Chapter 20 is very specific about where the boxes are taken, including reference to the deeds to houses that Dracula has bought (358). He sends six boxes to 197 Chicksand St., Mile End New Town. This fictional address in Whitechapel / Stepney would have had particular resonance in 1897. Not only was it one of the working class areas that had been the focus of concerns about poverty and crime, it was also associated with immigrants who came in through the docks, especially Jewish and other people from the East. Since the 1870s, the East End had been a site for panics about working class degradation, crime and disease. It was also the focus for fears of immigration, expressed in anti-semitic and orientalist discourses.

Moreover, Whitechapel would be remembered by Stoker’s readers for the 1888 Jack the Ripper murders (four women were murdered in Whitechapel and Spitalfields, the fifth nearby in the City). In Judith Walkowitz’s discussion of the journalistic construction of the Ripper murders, she comments that it constitutes ” a male-directed fantasy, [close] in tone and perspective to the literature of urban exploration and the male Gothic.”[13] The representation of London in Dracula and the location of some of its key moments draws significantly on the discourses that surrounded the Whitechapel murders, adding a contemporary frisson to the figure of the vampire. Newspapers described Whitechapel as,

a notorious, poor locale, adjacent to the financial district (the City) and easily accessible from the West End . . . . To middle-class observers, Whitechapel was an alien place, a center of cosmopolitan culture and entrepot for foreign immigrants and refugees . . . . [T]he middle classes of London were far less concerned with the material problems of Whitechapel than with the pathological symptoms they spawned, such as street crime, prostitution, and epidemic disease.[14]

The Times saw Whitechapel and the East End as a source of contamination, using an analogy with organic material that echoes Stoker’s choice of boxes of soil for Dracula’s self-reproduction:

We have long ago learned that organic refuse breeds pestilence. Can we doubt that neglected human refuse as inevitably breeds crime, that crime reproduces itself like germs in an infected atmosphere, and becomes at each successive cultivation more deadly.[15]

The remaining places where boxes are deposited also have significance. Six are taken to Jamaica Lane, Bermondsey, suggesting a foothold for Dracula in a commercial and small scale industrial working class area close to the river and the docks. This fictional address — ‘Jamaica’ — signifies its colonial links and financial importance. The remaining nine boxes are taken to a house in Piccadilly at the heart of the fashionable West End. This house, which Dracula has bought, gives him a commanding position adjacent to political and gentlemen’s clubs (it is just “beyond the Junior Constitutional” (316), probably based on the Junior Athenaeum on the corner of Down Street and Piccadilly) and overlooking Green Park (356). It is also significantly at the west end of Piccadilly, near to Buckingham Palace Gardens. In the contrasting locations for Dracula’s boxes we can perhaps also see the lingering influence of the panics about, and mythologising of, the Ripper. Amongst various suspects and scapegoats (including the figure of the fanatical and violent Jew) was the theory that the Ripper was a respectable professional West End man with a divided personality – a Jekyll and Hyde figure. Stevenson’s novella, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde had been published in 1886 with a stage version in 1888. Journalists used the literary reference to promote the idea of the Ripper as an alternative West End monster. Thus we can perhaps see the juxtaposition of Whitechapel and Piccadilly in the novel as Stoker borrowing from fiction and from recent events to centre anxieties on Dracula. Certainly, contemporary speculation about the identity of the Ripper – a mad doctor, an aristocrat, a Jew – has some striking parallels with the cast of Dracula. Dracula himself is an aristocrat, linked physiognomically and ideologically with Jews, and closely associated with the mad house at Purfleet. It takes a team including an English aristocrat and two doctors to defeat him. The estate agents tell Arthur (now Lord Godalming) that a ‘Count de Ville'[16] bought the house “paying the purchase money in notes ‘over the counter’, if your lordship will pardon us using so vulgar an expression” (326). The ‘”vulgar expression” suggests that we should read Dracula as counter-jumper, rather than an English gentleman, and not one of us. As well as indicating Dracula’s aristocratic origins, if we translate the French literally it also suggests that he is ‘man of the town or city’ . Dracula is perfectly at home in London in ways that none of his opponents can ever be. Jonathan is a provincial solicitor, Arthur belongs in Surrey (Godalming), Van Helsing in Holland, and Quincy in the American west. It takes their concerted efforts to force him out of London and back to Transylvania.

Links to Maps

Key to maps (numbered east to west)

1. Purfleet, Essex. Dr Seward’s asylum and Dracula’s house, Carfax

2. ‘197 Chicksand Street, Mile End New Town’ ( Mile End Road, Whitechapel) – location of 6 boxes from Carfax

3. ‘Jamaica Lane’, Bermondsey – location of 6 boxes

4. Fenchurch Street Station (trains from Purfleet)

5. Liverpool Street Station (boat trains from Holland)

6. Great Eastern Hotel, Liverpool Street (Van Helsing stays here)

7. ‘Chatham Street’ Southwark (Lucy staying here p.71)

8. King’s Cross Station (unloading of boxes from the Whitby train)

9. Regent’s Park and Zoological Gardens

10. Hampstead Heath (site of Lucy’s attacks on children)

11. ‘Kingstead’ churchyard (Lucy buried here)

12. ‘Hillingham’ – Lucy’s family home

13. ABC café near Piccadilly Circus (Jonathan p.318)

14. Sackville Street (estate agent)

15. Albemarle Hotel, Piccadilly (Arthur writes from here p.134)

16. Berkeley Hotel, Piccadilly (Van Helsing stays here, and Jonathan p.317)

17. ‘Giuliano’s’, Piccadilly (first London sighting of Dracula p.206-7)

18. Dracula’s house, Piccadilly

19. Jonathan and Mina’s walk from Hyde Park Corner, in Rotten Row, then down Piccadilly p.206

20. ‘The Stores’, Knightsbridge (Lucy meets Dr Seward p.138)

Endnotes

[1] Judith R Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London Virago 1992 p.26.

[2] ‘London, the World City’ is the title of Asa Briggs’s chapter in Victorian Cities, 1963

[3] Bram Stoker, Dracula 1897; Penguin 1979 p.9. All other references are to this edition.

[4] Leonard Wolf (ed.), The Essential Dracula, Plume 1993 p.31

[5] Franco Moretti, Signs Taken For Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms 1983 (in Glennis Byron (ed.), Dracula – Contemporary Critical Essays, Macmillan New Casebooks 1999 p.46)

[6] Even by association. His return travel arrangements are made in Galatz by “a Hebrew of rather the Adelphi type, with a nose like a sheep, and a fez” (415).

[7] Stephen Arata, Fictions of Loss in the Victorian Fin de Siécle: Identity and Empire, Cambridge UP 1996 p.108.

[8] Jonathan Schneer, London 1900: The Imperial Metropolis, Yale UP 1999; 2001 p.99

[9] Raymond Williams, The Country and the City, Paladin 1973 p.280.

[10] Walter Benjamin, ‘Baudelaire, or the streets of Paris’, The Arcades Project, trans.H. Eiland & K McLaughlin Harvard UP 1999 p.10.

[11] Walkowitz, 1992 p.24.

[12] The Arcades Project, p. 417-8.

[13] Walkowitz, p.192

[14] Walkowitz p.193

[15] The Times, 2 October 1888 quoted in Walkowitz p. 195

[16] A generic name for an aristocrat, see Wolf’s note in The Essential Dracula p.326

To Cite This Article:

Gill Davies, ‘London in Dracula; Dracula in London’. Literary London: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Representation of London, Volume 2 Number 1 (March 2004). Online at http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/march2004/davies.html. Accessed on [date of access].