David Ashford

(University of Surrey, UK)

The Literary London Journal, Volume 10 Number 2 (Autumn 2013)

[Clicking on the images in this essay brings up a large, high-quality version of the image]

The temple is perfected on the killing of the architect. The masterword being withheld, his assailants strike the skull three times, with plumb-rule, level and maul. In recoil, passes from south to north, between pillars of brass (each bears a ball: the giving and receiving of strength), to the east and: collapses to a pavement (chequered, white and black flag). The body is buried on top of a hill. The grave is a secret marked with a sprig of acacia.

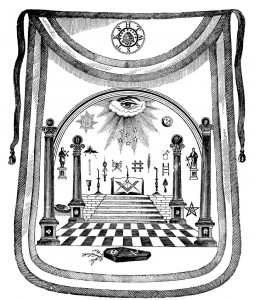

This is the Third Degree. To acquire the name of a Master-Mason, the Initiate must proceed through a diagrammatic map or plan; the story of the architect plays out on a schematic representation of the temple-complex, a mnemonic device surely inspired by the method of loci, or Memory Palace, spoken of in the Rhetorica ad Herrenium. ‘Persons desiring to train this faculty (of memory) must select places and form mental images of the things they wish to remember’, wrote Cicero (Book II, lxxxvi, 351-4). In so doing, practitioners produce an imaginary architecture they enter at will, a series of spaces that contain objects. In order to recall the content, say, of a speech, a speaker proceeds from room to room, revisiting the memorial placed in each (Yates 1-2). To enact the pattern on a Mason’s Carpet is to reactivate a sort of memory board; lost to Western Europe for several centuries, artefacts like this were the information technology of the Ancient World. Apparently introduced into Masonic practice by James Anderson in the years between 1723 and 1729, the image of the ‘Legend of the Temple’ does not merely signify but realises the resurrection of classical learning taking place in that period. In practicing the narrative space mapped out upon the floor, the man is reconfigured as mason, the mind is restructured in line with new or rather revived conceptions of classical space members of the group were then producing in London. The topographical and psychological spaces of the city that rose from the ashes of the Great Fire converged upon the monumental (From the Latin monere: ‘to mind’).

Given this last point, it is unsurprising that the Brotherhood of Free and Accepted Masons have figured so prominently in that body of London writing since labelled psycho-geographical – a term coined by Guy Debord of Lettrist International in 1955 to describe the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on emotions and behaviour of individuals. From the beginning, in texts such as Iain Sinclair’s Lud Heat (1975), Peter Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor (1985), Stewart Home’s Mind Invaders (1991) and Alan Moore’s From Hell (1989), the spaces of this secret society have been central to psycho-geographical literature in the UK; the extent to which Masonic theory and practice have produced the physical and psychological spaces of the modern metropolis has been a recurring theme. In Peter Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor, for instance, the churches of the Freemason Nicholas Hawksmoor are explicitly identified with contemporaneous transformations in literary form that would ultimately result in the novel:

I have finished six Designes of my last Church, fastned with Pinns on the Walls of my Closet so that the Images surround me and I am once more at Peece. In the first I have the Detail of the Ground Plot, which is like a Prologue in a Story; in the second there is all the Plan in a small form, like the disposition of Figures in a Narrative; the third Draught shews the Elevation, which is like the Symbol or The of a Narrative, and the fourth displays the Upright of the Front, which is like to the main part of the Story; in the fifth there are designed the many and irregular Doors, Stairways and Passages like so many ambiguous Expressions, Tropes, Dialogues and Metaphoricall speeches; in the sixth there is the Upright of the Portico and the Tower which will strike the Mind with Magnificence, as in the Conclusion of a Book. (Ackroyd 205)

But what to make of the fact that Hawksmoor’s neo-classical buildings are the subject of what is unmistakably a gothic narrative? For this is a book of uncanny doubling. Hawksmoor has been re-imagined as a police officer stalking the dark phantom of himself – an eighteenth-century architect represented as shadow to the Enlightenment. Having been commissioned to build monuments to the rational religion, championed by his master Christopher Wren, he has instead produced structures that incorporate satanic secrets: ‘I, the Builder of Churches, am no Puritan nor Caveller, nor Reformed, nor Catholick, nor Jew, but of that older Faith which sets them dancing in Black Step Lane’ (Ackroyd 20). In fact, the whole body of psycho-geographical literature on Masonic architecture could be characterised as a subgenre of the gothic. Sinclair’s study of Hawksmoor draws heavily upon the fiction of HP Lovecraft, and Moore implicates the churches in the Ripper Murders that took place two-hundred years after they were built. But on the face of it these uncompromisingly neo-classical buildings are not what one might consider an obvious setting for a genre of literature that has (from its inception) been inextricably bound up with the architectural style known as Gothic Revival. Horace Walpole – the creator of The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic Story – also commissioned the original gothic folly: the suburban castle up on Strawberry Hill. Indeed, according to one critical introduction to the genre, the most obvious justification for the use of ‘gothic’ as a literary term was by analogy with the movement in architecture, which also began in the mid-eighteenth century (Clery 21). The existence of a significant contemporary sub-genre that situates gothic narratives in enlightenment forms of thought, invests neo-classical space with gothic gloom, crystallises the suspicion now surrounding the term: the recognition that ‘Gothic as an aesthetic term has been counterfeit all along’ (Hogle 14).

In seeking to explain how Hawksmoor’s churches – and neo-classical spaces more generally – became generators for everything the New Architecture was meant to exclude, the following essay must cast light on questions that continue to animate gothic studies. The neo-classical spaces explored in much recent psycho-geographical fiction were produced in the decades immediately preceding the taste for gothic, or rather neo-gothic, in literature and architecture, and the present study should therefore be helpful in the ongoing attempt to establish that process whereby the gothic became gothic. I begin with a consideration of Hawksmoor’s life and work; rejecting the idea that either are inevitably grist for a gothic mill, I situate this church project within the context of the rebuilding and expansion of London after the Great Fire, arguing that the churches, as part of the wider history of Masonic activity in the capital, require a re-evaluation of what we understand by the urban uncanny. In so doing this essay will be pursuing the path beaten out by Julien Wolfreys and Roger Luckhurst, the pioneers in this new field of gothic studies, while seeking to extend this further into territory as yet unexplored.

It is the prototype of the Ripper Tour. The fourth chapter of Alan Moore’s From Hell takes the reader on a coach-ride across London, offering insights into the murders that took place in the Fall of 1888. But this tour is set before the event – and is conducted by ‘Jack the Ripper’. ‘We must consider our great work in ALL its aspects’, explains the killer to his coachman (Chapter 4, 8). His commission to remove ‘certain women’ who threaten the crown is merely the occasion for creative engagement with the patterns of history and myth that make up the modern metropolis (Chapter 4, 8). Beginning at Kings Cross, where Queen Boadicea died in battle with the Roman Empire, the tour proceeds to Hackney, where Saxons toasted Ivalde Svigdur, the man who killed the moon, then Bunhill Fields and the obelisk on the grave of Daniel Defoe. In the course of this the guide will interpret London’s built-environment as a monument to the primordial rebellion of men against matriarchal power. In the view of Jack the Ripper, ‘’Tis in the war of Sun and Moon that Man steals Woman’s power; that Left brain conquers Right … that reason chains insanity’ (Chapter 4, 21). This misappropriation of woman’s prophetic power finds its most forceful expression in the five chains set into the stone about the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral. Formerly the site of a temple sacred to Diana the current structure is now said to be a temple to the Sun, named after that ‘staunch misogynist’ beaten by the goddess at Ephesus: ‘Here is DIANA chained, the soul of womankind bound in a web of ancient signs’ (Chapter 4, 35).

In From Hell, the city’s architecture emerges as an aeon-long conspiracy on the part of the male principle, involving the manipulation of stone and symbol. The violence that follows later in the graphic-novel will therefore not admit of only one solution. As in a detective story, everyone in the region is a suspect, having both motive and means (the entire city being exposed as systematic form of misogyny), but in contrast to, say, a story by Agatha Christie, Moore’s graphic-novel refuses to resolve the ontological uncertainty the genre opens up, stating that the Ripper must be recognised as a super-position: the sum of all the possibilities presented by London in 1888 (Appendix 2, 16). The Ripper ultimately turns out to be, not William Gull, but the single point upon which the oppressive energies generated by the architectural structures mapped in Chapter Four converge. The tour concludes in the centre of the mosaic of the sun beneath the dome of St Paul’s. Having marked on a street-map each building visited in the course of their journey through London, the Ripper asks his coach-man to join the dots: and discovers an ‘earthbound constellation’ (Chapter 4, 19). The pattern is the five-pointed star, ‘pentacle of Sun God’s obelisks and rational male fire, wherein unconsciousness, the Moon and Womanhood are chained’ (Chapter 4, 36).

Most of the points on this map indicate the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor – and his ‘cheerless soul’, his ‘personality encoded into stone’, emerges as the moving spirit behind the Masonic conspiracy (Chapter 4, 32). Even St. Paul’s – designed by the original Grand Master of the Lodges, Christopher Wren – seems to be included in Moore’s pattern because Hawksmoor played a part in its creation (Chapter 2, 14). In fact, Moore acknowledges that much in this chapter was chiefly inspired by a meditation on the psycho-geographical properties of the Hawksmoor churches: the narrative poem Lud Heat by Iain Sinclair. In this book, Sinclair develops Alfred Watkin’s theory of ley-lines: his belief that prehistoric landmarks of the British Isles are aligned in a such a way as to produce huge invisible networks, and that such alignments are still there even in urban landscapes: ‘There are curious facts linking up orientatof force active in this city’ (Sinclair 18-9). This would produce a triangle in the east. If churches to the west and south were to be included the result is an irregular polygon. Sinclair likens this to the ‘symbol of Set, instrument of castration or tool for making cuneiform signs’ (16). The pattern is further complicated by sub-systems of obelisks (towers at St Luke, Old Street, St John, Horselydown and the obelisk of Thothmes III on the Embankment).

This network of ley-lines is rather less ion with the ley system illustrated by some London churches’ (Watkins 25). According to Sinclair, each of Hawksmoor’s ‘great churches’ is ‘an enclosure of force, a trap, a sight-block, a raised place with an unacknowledged influence over events created within the shadow-lines of their towers’ (Sinclair 20). If one were to mark out the total plan of churches on a map – like that provided in the book by Sinclair’s friend and fellow-poet Brian Catling – one could trace ‘lines of influence, the invisible rods spectacular than the pentacle-star discovered by Moore, and one can detect a shade of frustration (in his Appendix to From Hell) in the note in which he discovers the arbitrary nature of the map created by Sinclair and Catling:

After weeks of research and a day-long trip around key points of the diagram, only one point eluded me, this being the point on Sinclair’s map that is labelled ‘Lud’s Shed’. Even though I knew that the spot must be somewhere in the suburbs of Hackney, near to the London Fields, I could locate no reference to any such place as Lud’s Shed. Finally, in despair, I contacted Mr Sinclair himself, who informed me that the inclusion of Lud’s Shed at that point in the diagram had been a personal reference shared between himself and Mr Catling. (Moore Appendix I, 11).

In later editions of Lud Heat, this mysterious spot, marked on the chart with the Eye of Horus, is rather more clearly designated: it is Iain Sinclair’s house on Albion Drive.

In contrast, Moore is at pains to stress that every one of the points on his Ripper Trail has a historical rather than a merely personal significance: each has been ‘verified’ (Appendix I, 11). But this fact only serves to highlight the extent to which one must struggle to elicit any pattern – occult or otherwise – from the alignment of Hawksmoor churches alone. ‘He was the force behind the operation, the planning was in his hands’, insists Sinclair: ‘So that what we are talking about is not accident’ (14). But this faith in the strategic capacity of the architect is simply not compatible with the historic background on his church project, given at the start of Lud Heat. Here Sinclair notes that the Act of Parliament of 1711 provided taxes for the acquisition of sites, burial grounds, and parsonages, and that there was the round notion of 50 churches – but when the Commission of the Building of the New Churches discharged the Surveyors, Hawksmoor and John James, in 1733, only a dozen had been completed (13). If the occult network of sight-lines Sinclair describes truly were intended by the architect it was far from being realised. How then is one to explain the tenacity of this myth in the psycho-geographical fiction of the UK?

In part the existence of this myth must be seen to testify to the overwhelming illusion of power and mystery projected by the architecture of Nicholas Hawksmoor. His brief was to achieve ‘the most Solemn & Awfull Appearance both without and within’ (00). And it is worth noting in this context that, contrary to suspicions entertained by the psycho-geographers, the nature of this project, thus defined by John Vanbrugh, must have displeased Hawksmoor politically because (as Kerry Downes points out) the architect was an outspoken Whig (Downes 105). The Act of Parliament in 1711 had been pushed through by the Tories, in response to the clergy’s fears that the non-conformist sects that had played such an important part in the revolution of the previous century were now flourishing in the East End. The creation of Anglican church-buildings in these new neighbourhoods (fifty of them!) was intended to stamp out a political threat. The churches would reassert the authority of the state religion in spaces that the government had long since lost the opportunity to shape and control. This is precisely why this aggressively expansive church-building project was so soon halted. In 1714 the return of the Whigs to power, following the succession of George I, put the project under new management, hostile to the objectives that had motivated their predecessors and determined to restrict the number of churches built to those that were already in hand. The churches began as objects that were hated by their reluctant parishioners, and at certain moments in their subsequent history have become quite transparently what they always were. When French refugees living in Whitechapel protested in the eighteenth century at the decline in their trade, the troops that crushed the uprising were barracked in Christ Church. That Hawksmoor’s churches continue to project this illusion of state control – blamed in contemporary psycho-geographical literature for crimes resulting from the state’s failure to prevent economic and societal breakdown – is a perverse measure of the extent to which the architect had succeeded in fulfilling his brief. ‘These are centre of power for those territories’, notes Sinclair; ‘sentinel, sphinx-form, slack dynamos abandoned as the culture they supported goes into retreat. The power remains latent, the frustration mounts on a current of animal magnetism, and victims are still claimed’ (15).

From the start, writers have struggled to speak of the aesthetic effects achieved in the churches without resort to the term gothic – whether in the literary or architectural sense. In 1734 the Palladian critic James Ralph condemned the church buildings as ‘Gothique heaps of stone, without form or order’ – criticism rejected by Hawksmoor for the improper ‘use of the word Gothick to signifye every thing that displeases him, as the Greeks and Roman calld every Nation Barbarous that, were not in their way of Police and Education’ (Downes 160). But long after the rehabilitation of the term with the Gothic Revival, contemporary writers tend to speak of the churches in much the same way as Ralph. In Moore’s From Hell, the Ripper claims that, ‘Hawksmoor cut stone to hold shadows; a Gothic trait, though Hawksmoor’s influences were somewhat … older’ (Moore 2.14). The observation echoes the depiction of Hawksmoor’s work as an Art of Shadows in Ackroyd’s novel: ‘It is only the Darknesse that can give trew Forme to our Work and trew Perspective to our Fabrick, for there is no Light without Darknesse and no Substance without Shaddowe’ (Ackroyd 5).

This characterisation is not without basis in fact. In the course of creating the London Underground Headquarters building and Senate House for the University of London (in the streets immediately behind St George Bloomsbury), Charles Holden reflected on the properties of his building material, Portland Stone. In addition to being resilient and resonant of London’s past, he noted that no other stone can at once be stained so dark by the atmosphere and yet weather so white when exposed to rain. Hawksmoor cannot have been unaware of the striking chiascuro effect he would achieve in setting recessed windows into walls that would shine out all the more brightly about them, white and flat.

But to suggest that this art of shadows, if it be such, is equivalent to the gloom of the gothic-horror is misleading. In spite of often-cramped urban settings, Hawksmoor’s churches produce spaces, inside and out, that are open, airy and light. To walk about Christ Church, Spitalfields after a shower is to experience the polar opposite of what Moore has described in From Hell, when ‘even on the brightest days, the surrounding streets are drowned and lost in its shadow’ (Appendix 1, 16). Christ Church shines too brilliantly to look at; the surrounding streets illuminated by the light it reflects. If Moore is right in suggesting that the tower has a ‘subliminal menace’, this cannot be explained by relating this structure to what is meant by gothic in either literature or architecture. As Kerry Downes points out: that the churches remind us of gothic structures is incidental. At Wapping, for instance, ‘From the west the tower appears to burst upwards from the ground, splitting the pediment in two with a force we usually associate with the soaring lines of Gothic towers; yet the conscious origins of Hawksmoor’s towers do not seem to be Gothic’. In fact, in most instances the derivation is demonstrably classical: ‘he arrived at the forms of the two Stepney steeples wholly by means of Renaissance or Antique detail’ (Downes 121).

To underline this point: Hawksmoor’s churches are fundamentally unlike gothic buildings. Though both share a similar upward momentum, the gothic is diffuse where Hawksmoor is concentrate. Throwing out arches, buttresses, flying-buttresses, gothic supports its giddy ascent by striving for a lightness that is achieved through dispersal of the outward thrust generated by weight of roof and spire. Hawksmoor’s churches, in contrast, marshal energy not to be released. Load-bearing elements are typically emphasised, appearing too big for the weight that they support: pillars, pilasters and piers, too massy or long, project an upward force that is stressed through out-sized cornices, through elements above this pedestal which seem too far set back, too light a load for the emphatic machinery beneath; basement windows push up out of the earth, headed by colossal triple key-stones; roman-arches punch up through string-line and cornice, puncture the pediment. These building are at once energetic and oppressive; what looks to be an unstoppable momentum skyward – is held, pent up, in torsion. Tectonic forces strain within a feeling for form, an impending subterranean outburst remains just under control.

To understand where Hawksmoor’s churches are coming from, consider the first proposal he produced in response to the Commission’s request for ‘one general design or Forme’ for the churches. His hypothetical plan for a ‘Basilica After the Primitive Christians’ is a sketch in pencil and sepia ink with thin blue wash to indicate sacred precincts, of a Roman palace in a graveyard complex, which attempts a reconstruction of the ‘Manner of Building the Church as it was in ye fourth Century in ye purest times of Christianity’ (De La Ruffiniere du Prey 38-52). Hawksmoor was taking church-architecture back to its origin, to the moment the new faith emerged from the catacombs (subterranean pagan burial grounds in which it had been compelled to shelter in the first centuries of persecution) in order to begin adapting Roman basilicas for the Christian ritual. The result is a bricolage – cobbling together of pre-existing architectural elements – of symbols and structures – developed by pagan cultures from across the Ancient World. Considered in relation to Hegel’s thoughts on the origins of architecture, Hawksmoor’s project must be seen to be repeating that first imitation and above-ground blossoming of a buried architecture that Hegel considers no ‘positive building but rather the removal of a negative’ (Hegel 649). Hawksmoor had taken architecture back to the beginning – not merely to the beginning of Christian architecture – but to the original re-production above-ground of that emptying that makes a space for the dead. According to Hegel, the pyramid marks the point at which architecture became a positive procedure but ceased to possess an independent meaning, was itself emptied, negated. ‘In this way pyramids though astonishing in themselves are just simple crystals, shells enclosing a kernal, a departed spirit, and serve to preserve enduring body and form’, writes Hegel. ‘Therefore in this deceased person, acquiring presentation on his own account, the entire meaning is concentrated; but architecture, which previously had meaning independently in itself as architecture, now becomes separated from meaning and, in this cleavage, subservient to something else’ (653).

Incorporating Roman altars, Etruscan urns, Egyptian obelisks, horologions, pyramids, the Mausoleum of Kos, into structures that would represent the triumph of a rational faith over pagan magic, Hawksmoor was attempting to manipulate signs that could not be relied upon to stimulate the one idea which their erection aimed at arousing, ‘for they can just as easily recall all sorts of other things’ (Hegel 636). Hawksmoor could not realistically hope to impose limits upon the signifying potential of the resulting bricolage – a fact that might have occurred to him had he questioned the Protestant assumption that the first centuries of the Christian Era were ‘ye purest’. As Edward Gibbon would later demonstrate, this was the great age of heresy, a time of flamboyant hybrids. Indeed, it is tempting to connect its syncretic approach to religion with that syncretic architecture Hawksmoor emulated. ‘Relate them to the four Egyptian protector-goddesses, guardians of the canopic jars’, writes Sinclair. ‘I associate these churches with rites of autopsy on a more than local scale’ (28). In the light of Hegel’s thoughts on the beginning of architecture, Sinclair’s comparison of the pyramids set into the ground near the eastern churches to the brains removed from a mummy is most suggestive. Like Egyptian coffins, the churches are inactive engines, layers upon layers of symbol that insist on interpretation. But despite being endlessly open-ended, the brutally forceful, formal properties of these churches will not concede any reading (however outré) to have been unforeseen or unintended by the architect. They are perfect mechanisms for the production of paranoia.

Hawksmoor’s proposed and actual use of pyramids, sphinxes, obelisks, sacrificial altars must seem incompatible with our ideas of the eighteenth century as an age that privileged reason over traditional wisdom, and this is reflected in some of the recent fiction inspired by the architect. In Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor, the protagonist is depicted as diametrically opposed to the rationalism embodied in that novel by Sir Christopher Wren. In the course of a visit to Stonehenge the two characters are shown talking at cross-purposes for the best part of a chapter; oblivious to the pleasure his student is taking in what he feels to be a space for blood sacrifice, Wren runs about the structure taking measurements, expressing his delight at being able to say that logarithms are a British invention. But the exceptional nature of Hawksmoor’s work is not so defined in other psycho-geographical fiction. The binary in Ackroyd is very much what one might expect in a gothic novel: forces repressed by a scientific culture return to haunt the present. In contrast, the most remarkable feature of writing by Moore, Sinclair and Home is the extent to which all of this break with the familiar gothic paradigm. St Paul’s is part of the pattern in From Hell. The British Museum and the Observatory at Greenwich are significant in the survey in Lud Heat. And in the psycho-geographical bulletins of Stewart Home, the entire world-heritage site at Greenwich, consisting of buildings designed by Inigo Jones, John Webb, Nicholas Hawksmoor and Sir Christopher Wren, stands accused of being a Masonic conspiracy to harness energies of the ‘ley-line’ more generally known as the Prime Meridian, to conjure the British Empire into existence, and later to reinforce the power of an ‘Occult Establishment’ (see the bulletins of the London Psychogeographical Association reproduced in Home). In this deliciously paranoid material, Hawksmoor is presented not as atypical but archetypal. His acknowledged interest in Egyptian hieroglyphs, freemasonry, his proposed and actual use of magical funerary objects, is not opposed to but intrinsically a part of the movement toward neo-classicism in the culture of the period.

Surprisingly, the most recent architectural historian to have written extensively on Hawksmoor might endorse this assessment. ‘It may seem paradoxical that, despite the early eighteenth century’s appeal to reason, this was also the period of rapid growth in freemasonry as an institution, whose attraction lay in its apparent mystery, ritual, secrecy and quest for hidden truth,’ writes Vaughan Hart. ‘Nevertheless, behind this cultivation of ancient mysteries and signs lay a rational approach to religion based on the non-sectarian theology of Deism’ (98). Thus, the occult history of the Masons written up and published by John Anderson has been very closely modelled on the history of architecture advanced by Wren and Newton. And even the most freakish use of pagan funerary objects in Hawksmoor’s projects – the Mausoleum set upon the tower of St George Bloomsbury – can be seen to have had its origin in a sketch Hawksmoor produced for the last of Wren’s tracts on architecture. His interest in the Christian Basilica was merely part of a more general interest, on the part of those architects working with Wren, in recovering alternative traditions of architecture that might provide the Reformed Church of England with a form of building suitable to its needs, that would reflect its break with the medieval past.

Hawksmoor’s mechanisms for paranoia, installed to secure a psycho-geographical hold upon non-conformist parishes of the East End, can be traced back to the creative procedures developed by the Wren Office as a whole: in response to their collective failure to impose a rational plan upon the City of London. ‘They had so favourable an opportunity to Rebuild London ye most August Towne in ye world,’ complained Hawksmoor in his letter to Dr Brooke in 1712, ‘and either have Keept it to its old Dimention, or if it was reasonable to let it swell to a Larger, they ought for ye Publick good to Guided it into a Regular and commodious form, and not have sufferd it to Run into an ugly inconvenient self destroying unweildly Monster’. He was referring to the Great Fire of 1666, an event that visited a devastation that was unprecedented upon the historic centre of the largest city in Europe. The Great Fire wiped out 13,200 houses, the Royal Exchange, the Custom House, the halls of the City’s Companies, the Guild Hall and nearly all the City buildings, St Paul’s Cathedral, and eighty-seven of the parish churches. In total the bill was reckoned at more than £10 million, and 80,000 people were made homeless (Tinniswood 4, 101). The work of a thousand years had been wiped out, leaving nothing but names. The weeks that followed were to witness concerted attempts to overcome this profound erasure of urban topography: rationalised street-plans that simplified and geometrised the city, thereby rendering the new alien spaces immediately graspable.

The most famous, most influential, of the Fire Maps was created by Christopher Wren (King’s Surveyor of Works from 1669). His plan presented a radical break with the informality of the medieval city, introducing an inventive combination of new ideas for town-planning. In the west, the plan calls for an asterisk street-plan over the region about Fleet Street: a piazza in the centre from which lines of straight main-streets radiate out. To the East, the plan envisages the grid pattern now standard in the United States, but with much wider streets cutting through this at a diagonal from the piazza about St Paul’s Cathedral. These extend to a series of other asterisk patterns, or star-bursts, towards the Tower; the greatest of which contains the Royal Exchange. The plan opens up clear lines of sight within the city – many culminating in monuments to the power of the State – an official building, or a statue or a church. But the scheme was defeated by ‘the obstinate Averseness of great Part of the Citizens to alter their Old Properties, and to recede from building their Houses again on the old Ground and Foundations’ (Wren et al 269). If the view in the Wren family memoir Parentalia (1750) is an accurate representation of the Surveyor’s own opinions on this subject, it would seem that Wren shared, or even inspired, the belief of his assistant Hawksmoor: ‘By these Means, the Opportunity, in a great Degree, was lost, of making the new City the most magnificent, as well as commodious for Health and Trade of any upon Earth’ (269).

But citizens had good reason for distrust. London had been the heart of the English Revolution that had been put down only a few years previously with the Restoration of the Stuart Dynasty and was therefore perceived by courtiers such as John Evelyn as an urban space that was politically malfunctional. London is a ‘City consisting of a wooden, northern, and inartificiall congestion of Houses’, he wrote, before the Great Fire, in 1659, ‘as deformed as the minds & confusions of the people’ (Evelyn 9). The total transformation of space proposed in the plans would accordingly reshape the political principles of the populace; they would reform the bad character of the capital. Based on the models established in Paris and Rome, the Fire Maps created by these Royalist planners were specifically geared to extend the power of the State into everyday life. The men who laid out the new Rome, for instance, called main streets viae militares, or military ways, and Palladio had explicitly said, ‘the ways will be more convenient if they are made everywhere equal; that is to say, that there be no place in them where armies may not easily march’. Indeed, as the architectural historian Lewis Mumford insists: ‘This uniform oversized street […] had a purely military basis’ (369). In opening up lines of sight in the city, these plans were not just expressing the values of a culture that equated reason with light, but were facilitating the army’s movement through a space of political opposition, while frustrating the guerrilla tactics that had enabled a small group of puritan radicals to wreak havoc in the City just a few years earlier; they were enabling the monarch to monitor the populace, while impressing upon them his overwhelming power, through the monuments to Church and State which would terminate each axial route.

The Monument to the Great Fire provides by far the clearest insight into how the Surveyor conceived of his project. This structure incorporates a shaft into the central pillar, with spaces to slot lenses along the length. There is a laboratory basement beneath and a hatch in the ornament on the top. The building is in fact a device known as a fixed telescope (Jardine xi-xiv, 315-21). The Monument is a scientific instrument for the measurement of time and space. It is hard to imagine a clearer way to signal a total break with the messy contingency of the medieval past than this object, raised upon the spot that saw the Great Fire begin in closely packed wooden streets about a bread-oven. But in the relief, carved upon the western panel, the powers of reason and scientific endeavour are utterly identified with an authoritarian monarch, the one king in English history to rule successfully without Parliament as though by Divine Right. Each radial street-pattern or star-burst on the Fire Map, evinces the same ideological premise that underpins the Masques of Ben Jonson, or the painted ceiling under which these took place in the Banqueting Hall – the conflation of reason with the totalitarian political order imposed by the power of a Sun-King.

Having lost this historic opportunity to reform the medieval tangle of streets within the ‘liberties’ of London, the king’s town-planners were restricted to a superficial reordering of the urban environment. Royal proclamations insist that houses be built with brick instead of timber, to prevent against fire, that certain routes be widened and straightened, and that all the buildings should be built to a uniform pattern, the height of each building relating to its function and location (Wren 269). The end result was something that presented the appearance of the most modern city in Europe, built of brick and Portland stone, in a uniform and rational architectural style – but which was overlaid upon the old street-plan, an urban environment still fundamentally medieval or gothic. This disjunction is at its most pronounced in the centrepiece to the re-built London, St. Paul’s Cathedral.

After a false start (strange proposals for a complexs of detached buildings – produced in order to comply with an initially low-budget – that later evolved into Trinity College Library (Cambridge) and the hemispherical dome at St Stephen Walbrook), Wren produced a large scale model in wood of a neo-classical building that would have been the most radical cathedral structure in Western Europe. Drawing upon Bramante’s unrealised plans for St Peter’s Cathedral in the Vatican and the subsequent work of Michelangelo, Wren’s Great Model offered a definitive break with the gothic style. Where the plan of the former cathedral of St Paul’s was based on a Latin cross with long aisles suitable for processions, the plan of the Great Model is based upon a Greek cross – a square with the inner corners cut off – that would permit everyone in the church to see and hear everything without internal obstruction, reflecting the reformed religion’s emphasis on the spoken Word. Instead of a steeple propped up with buttresses, the Great Model called for a technologically innovative dome. And rather than an exterior broken up by flying buttresses (to hold up the wall), the Great Model presented clear-cut forms, flat surfaces that possess real volume and bulk. According to Parentalia, ‘the Surveyor in private Conversation, always seem’d to set a higher Value on this Design, than any he had made before or since; as what was labour’d with more Study and Success’ (Wren 282).

But in a sequence of events that echoes the lost opportunity to rebuild London, the Great Model was rejected by the Clergy on the basis that it was ‘not enough of a Cathedral-fashion; to instance particularly, in that, the Quire was design’d Circular’ (Wren 282). Wren therefore turned his thought to creating the plan now known as the Warrant Design; apparently put together in haste from a much earlier design for repairing the existing gothic cathedral, the proposal secured the consent Wren required in order to proceed, though the Great Model represented that which ‘he would have put in Execution with more Chearfulness, and Satisfaction to himself than the latter’ (Wren 282). If the final result looks rather more like the Great Model than the Warrant Design, this is because the architect had the king’s permission ‘to make some Variations, rather ornamental, than essential’, to reconcile, ‘as near as possible, the Gothick to a better Manner of Architecture’ (Wren 282-3). Examine the walls: these present the illusion of a solid block, consisting of two storeys like the Banqueting Hall of Inigo Jones, rather than the Great Model; but the upper storey is entirely façade, a blank wall to conceal the flying buttresses required by the plan, only there to bulk out the outer wall. Examine the dome – this is not a load-bearing cupola like St Peter’s (the plan rendered that impossible), but a sort of shell about a structure rather resembling the octagonal lantern above the late-medieval Ely Cathedral. What appears to be a dome is a skin made of lead and keyed to a concealed cone of brick (which supports the stone lantern above) with a scaffold of wood. In the cathedral as built we have a gothic structure: a Latin cross, lantern tower, flying buttresses. But with variations (rather ornamental than essential) that conceal this historic failure on the part of the King and King’s Surveyor to build a temple that would have embodied, rather than merely projected, the tyranny of political enlightenment. In order to maintain the illusion the cathedral had been transformed into a rational space, Wren had been compelled to develop an architecture that relied upon a sort of visual magic, a trompe de l’oeil.

From the start this discrepancy was to have peculiar and far-reaching consequences for the way in which Londoners have experienced their city. Take this passage from a Daniel Defoe’s Colonel Jack (1722)

Run, Jack, says he, for our lives; and away he scours, and I after him, never resting, or scarce looking about me, till we got quite up into Fenchurch-street, through Lime-street, into Leadenhall-street, down St. Mary-Axe, to London-Wall, then through Bishopsgate-street, and down Old Bedlam into Moorfields. … So away he had me through Long-alley, and cross Hog-lane, and Holloway-lane, into the middle of the great field, which, since that, has been called the Farthing Pie-house Fields. There we would have sat down, but it was all full of water; so we went on, crossed the road at Anniseed Cleer, and went into the Field where now the Great Hospital stands … (43)

Note the listing of place-names. As Cynthia Wall demonstrates, in her study of the Literary and Cultural Spaces of Restoration London (1998), this is typical in writing from this period – symptomatic of the shock induced by the erasure of the metropolis in the Great Fire. In Defoe city streets are still being named in order to grasp a terrain suddenly made strange. But there is more here: an effect like that of double-exposure, as Jack seems to run through two cities at once, superimposing the image of a past London onto the present: ‘historical past, the London known; and the passing of that past, the London destroyed’ (Wall 24). It is as though the prose is haunted by the gothic street plan that persisted beneath the modern superstructure. In presenting the illusion of a total aesthetic revolution without having truly achieved it, the rebuilding of London had produced precisely those conditions that Anthony Vidler, in a book on the architectural uncanny, considered to be ripe for uncanny sensations: ‘this uncanny’, wrote Freud, ‘is in reality nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression…. The uncanny [is] something which ought to have remained hidden but has come to light’ (Freud 241).

The reason the eighteenth-century literature of terror acquired a specifically gothic architecture is – at least in part – the result of a suppression at once brutal and incomplete. The neo-classical reconstruction of London had rendered the medieval ghost-like: killed organic forms that had evolved over a thousand years of communal struggle – but then left the grave shallow: had even formulated the aesthetic required for its return as revenant, no longer a living thing but an historical curio. Consider Wren’s St Mary Aldermary, Hawksmoor’s St Michael Cornhill, Vanbrugh’s Castle Maze Hill, the spire planned for Westminster Abbey or the towers by Hawksmoor on the western end. These buildings offered a concession to sentiment, an antiquarian inclination that anticipated the Gothic Revival. Note that Ruskin shared Wren’s hatred of buttresses, that Pugin’s Palace of Westminster resembles Hawksmoor’s western towers rather more than sections of Westminster Abbey actually built by Henry III. The Revival preferred an eighteenth-century fantasy of gothic architecture to the real thing, the simulacrum of the medieval produced to please modern taste by the Wren School.

But there is insufficient space to discuss this. The purpose of this essay is to explore the mechanisms that produce the unheimlich. Perhaps the most interesting implication of Vidler’s architectural uncanny is that incessant reference to avant-garde technique without the originating ideological impulse, the appearance of revolution stripped of social redemption, must produce a space doubly haunted – by every ghost the architects have not successfully laid – and by every apparition they have raised rather than made real. Such a distinction (not spelt out in Vidler’s book) would represent in architectural terms those crucial distinctions that Freud insists upon in his famous essay on ‘The Uncanny’ (1919): (1) The uncanny feeling that can be traced ‘without exception to something familiar that has been repressed’, and

(2) the uncanny ‘associated with the omnipotence of thoughts, with the prompt fulfilment of wishes, with secret injurious powers and with the return of the dead’ (247).

Freud notes that the former kind of uncanny is not of frequent occurrence in real life. As most of the examples offered are taken from the realm of fiction, the implication seems to be that this uncanny is usually aroused by imaginative writing – and this is interesting given the extent to which this particular variety of uncanny has dominated the gothic genre. It is the latter sort of uncanny that is much more likely to belong to actual experience (248). Such uncanny effects are often and easily produced, writes Freud, ‘when the distinction between imagination and reality is effaced, as when something we have hitherto regarded as imaginary appears before us in reality or when a symbol takes over the full functions of the thing it symbolizes’. He suggests that this ‘is the factor which contributes not a little to the uncanny effect attaching to magical practices’ (244). And Freud confesses that he would ‘not be surprised to hear that psychoanalysis, which is concerned with laying bare these hidden forces, has itself become uncanny to many people for that very reason’ (243). Of course ‘we must not let our predilection for smooth solutions and lucid exposition blind us to the fact that the two classes of uncanny experience are not always sharply distinguishable’ (249). His description of the first class as one in which the frightening element is something repressed that recurs, certainly recalls the epigraph to Sinclair’s Lud Heat, ‘All perils, specially malignant, are recurrent’ (Fredu 241; Sinclair 13. The epigraph is from De Quincy, On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts, an appendix to which recounts the history of the Ratcliffe Highway Murders). But what is distinctive about psychogeographical fiction is clearly to be connected to the second class: – an attention to those ‘magical practices’ that are capable of reactivating a superstitious conviction in the omnipotent psychokinetic capacities of the practitioner.

In closing I should like to observe that, though the phenomenon that is here explored has been occluded in the English ‘gothic’ tradition, to such an extent that one is hard pressed to speak of it without resorting to terms that must mislead, the attention Freud bestows equally upon the uncanny we associate with the revenant and that we would relate to occult practices, serves to highlight the prominence of the latter in German literature. If the earliest gothic fiction in England is clearly a legacy of the historical rupture produced by the middle-class rejection of feudalism, Catholicism and Europe – the horror resulting from fear of being subsumed by a resurrected past in the attempt to acquire that power – much of the contemporary literature of terror produced in the Holy Roman Empire concentrated upon subjects that have only recently received ‘gothic’ treatment in the UK. Friedrich Schiller’s Der Geisterseher (1789. English: The Ghost-Seer) had represented the agents of the Inquisition (Jesuits) and the agents of Modernity (Freemasons and Illuminati) as doubles of each other. The former are sufficiently familiar from the English tradition to require no comment. The latter appear to be unique in this period to the European tradition, and so might need some explaining. The rogue Mason in Schiller’s novel tapped into the fear that groups were psychologically manipulating people with visual and aural tricks, involving magic lanterns, magnets, electrical devices and gunpowder. ‘Once the mind of initiates had folded under the stress of inexplicable mysteries,’ explains Robert Miles, in his recent survey of this fiction, ‘their minds would be putty in the hands of their masters, who plotted the overthrow of monarchies across Europe’ (51).

Schiller’s novel gave rise to many imitations, such as The Necromancer by Carl Friedrich Kahlert (trans. 1795), The Victim of Magical Delusion by Cajetan Tschink (trans. 1795) and Horrid Mysteries by Karl Grosse (trans. 1796), which as their titles suggest focus on the uncanny effects to be achieved by agents of modernity manipulating an occult science. These were read with interest in England, but the writers of this country were ultimately to ignore Masons and Illuminati, in order to focus their creative paranoia upon the Jesuits (note the changes made in Anne Radcliffe’s adaptation of Schiller’s novel, The Italian (1797)). The Promethean figures that emerge after the French Revolution might signal an initial move on the part of English writers toward the European tradition; it is certainly very interesting to note that Ingolstadt, site of Dr Frankenstein’s experiments, is said to be the birthplace of the Illuminati (Miles 51). But to see so much, and such significant, ‘gothic’ fiction upon the Freemasons themselves appear suddenly from the late-seventies might suggest that a historic transition is taking place and that the coordinates of the ‘gothic’ are now being realigned to reflect a more general shift in attitudes toward the Enlightenment.

Of the four recent authors picked out in this essay, three are clearly heavily immersed in the sixties counterculture that saw a wholesale rejection of the modern project. And it is in the writing of these three – Sinclair, Moore and Home – that we see Masonic Lodges (identified by the philosopher Jurgen Habermas as central to the development of civic society) represented as agencies of horror not because they are a buried secret but because they are the established fact (Habermas 35). The positive publicity that the revenant has received in postmodern philosophy appears to be having interesting consequences for a genre of fiction that has relied heavily, in the English-speaking tradition at least, on the revenant to inspire terror. The contemporary situation is captured perfectly by a moment Moore describes in the notes to his novel, when he remembers addressing ‘Chaos magicians, Wiccans and assorted Diabolists’ in a public room formerly reserved for the local Freemasons (Moore Appendix 1, 28). What will the future hold for the ‘gothic’ genre now that the mainstream manifests such sympathy for the Devil? In psycho-geographical fiction we have one answer at least. The victor too has a compulsion to repeat. Blood is required by the agents of the Light.

Works Cited

Ackroyd, Peter. Hawksmoor. London: Penguin,1993.

Cicero. De Oratore, De Fato, Paradoxa Stoicorum, Partitiones Oratoriae. With an English translation by E. W. Sutton and H. Rackham. (Loeb Classical Library). 2 vols. London, Heinemann, 1942.

Clery, E. J. ‘The genesis of ‘Gothic’ fiction’, The Cambridge Guide to Gothic Fiction. Ed. Jerrold E. Hogle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Defoe, Daniel. Colonel Jack (1722). Ed. Samuel Holt Monk. London: Oxford University Press, 1965.

De La Ruffiniere Du Prey, Pierre. ‘Hawksmoor’s “Basilica After the Primitive Christians”: Architecture and Theology’. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 48.1 (1989): 38-52.

De Quincy, Thomas. On Murder Considered As One of the Fine Arts. London: Holerth Press, 1924.

Downes, Kerry. Hawksmoor. London: Praeger, 1970.

Evelyn. Character of England, As it was Lately Presented in a Letter, to a Noble Man of FRANCE. London: 3rd Edition, 1659.

Freud, Sigmund. ‘The Uncanny’ (1919), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works. Vol. XVII. Trans. James Strachey. London: Hogarth Press, 1955.

Habermas, Jurgen. The Structural Transformations of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (1962). Cambridge: MIT Press, 1989.

Hart, Vaughan. Nicholas Hawksmoor: Rebuilding Ancient Wonders. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002.

Hawksmoor, Nicholas. Letter to Dr Brooke. 1712.

Hegel, G. W. F. Aesthetics. Vol. II. Trans. T. M. Knox. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974.

Hogle, Jerrold E., ed. ‘Introduction’, Cambridge Guide to Gothic Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Home, Stewart. Mind Invaders. London: Serpent’s Tail, 1997.

Jardine, Lisa. On a Grander Scale: The Outstanding Life of Sir Christopher Wren. New York: HarperCollins, 2002.

Miles, Robert. ‘The 1790s: Effulgence of Gothic’. Cambridge Guide to Gothic Fiction. Ed. Jerrold E. Hogle. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 41-62.

Moore, Alan. From Hell. London: Knockabout Gosh Books, 1989.

Mumford, Lewis. The City in History. New York: Harbinger, 1961.

Sinclair, Iain. Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge. London: Granta, 1998.

Tinniswood, Adrian. By Permission of Heaven: The Story of the Great Fire of London. London: Jonathan Cape, 2003.

Vidler, Anthony. The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992.

Wall, Cynthia. The Literary and Cultural Spaces of Restoration London. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Watkins, Alfred. The Old Straight Track. London: Abacus, 1970.

Wren, Sir Christopher, Christopher Wren, Junior and Stephen Wren. Parentalia: or, Memoirs of the family of the Wrens … chiefly of Sir Christopher Wren. London: T. Osborn and R. Dodsley, 1750.

Yates, Frances. The Art of Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966, 2001.

To Cite This Article:

David Ashford, ‘The Mechanics of the Occult: London’s Psychogeographical Fiction as Key to Understanding the Roots of the Gothic’. The Literary London Journal, Volume 10 Number 2 (Autumn 2013). Online at http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/autumn2013/ashford.html.