Susan Trangmar

(Central Saint Martins University of the Arts, London, UK)

The Literary London Journal, Volume 10 Number 1 (Spring 2013)

[Clicking on the images in this essay brings up a large, high-quality version of the image]

To follow the dark paths of the mind and enter the past, to visit books, to brush aside their branches and break off some fruit. (Woolf, The Waves 605)

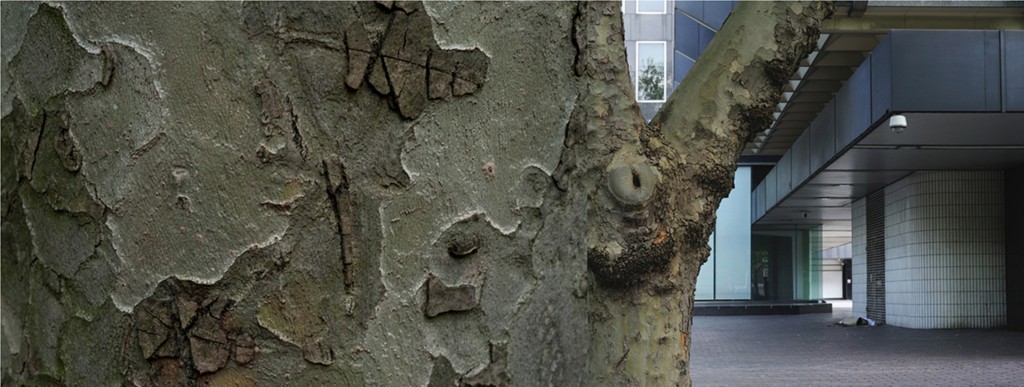

<1>In 2009 I began to photograph London plane trees in central London. The urban street tree is a ubiquitous presence, and we are all familiar with those landscape photographs in which the presence of the tree serves as no more than a formal prop in pictorial composition or as a single decorative specimen on architectural plans in order to fill so called ‘empty space’. However, the street tree serves many different purposes; it can act as marker of place, as register of time passing or as object of reverie, functioning as part of a matrix of signs and objects within the urban environment. In my photographic project ‘A Forest of Signs’, I am interested in ways that the street tree acts as both focus and frame for our perception and experience of the city. In so doing, the tree is a key figure in the construction of an urban imaginary through photography.

<2>It so happens that the institution in which I work – Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design – moved from Charing Cross Road and Southampton Row to Kings Cross in September 2011 after over 150 years of history in this part of central London. Perhaps my late act of walking, looking and photographing street trees was unconsciously anticipating this departure. After all, I studied at Saint Martins and have spent a large part of my working life traversing these streets. It was while photographing and considering the longevity of urban trees in relation to place, that I remembered having read Virginia Woolf’s Night and Day in the early 1980s and connected her characters rambling through the streets of Westminster, the Strand, Holborn and Bloomsbury with my own peripatetic reveries. Going on to re-read Woolf’s novels and short stories during this period gave me, amongst other things, an historical perspective on this project, for some of the trees I have passed, scrutinised and photographed may well have been noticed by her.

<3>Virginia Woolf’s writing is rich with descriptions of London life and lives in the early twentieth-century, but it is the image of the tree shot through the fabric of her writing that I began to notice. Trees for Woolf are a central image – a metaphor for the organic patterning of perception, memory and embodied experience, as witness and companion to the experience of place and as motif for the flux of time and being.

<4>So as Woolf would have walked, imagined and wrote, so I have walked, imagined and photographed. I became aware that my activity of photographing – and perhaps this is true of Virginia Woolf’s activity of writing also – partly acts as a defence against what is being lost to the past whilst at the same time acting as a bridge to the future. Reading Woolf’s fiction and essays has accompanied my working process, stimulating my thought at one remove. And so, in a strange way, Woolf’s writings concerning trees have come to shadow invisibly my photographs.

<5>What follows is an oblique dialogue between my urban encounters with trees through the medium of photography and passages from Virginia Woolf’s writing concerning processes of looking, imagining and writing through the figure of the tree.

<6>It is perhaps important to state here that the genres of literary writing and photography each retain their own integrity; I am not claiming that Woolf’s writing is structured like photography or that photography is structured like a literary narrative. Nor could I ever attempt through photography to match the poetic complexity of Woolf’s writing; rather I am interested in how photography and literature might inform one another.

<7>Whilst making these photographic images, therefore, I have found certain aspects of Woolf’s writing useful to consider:

- The simultaneity of thought and image as an embodied experience

- The spatial organisation of language (both visual and linguistic), which gives rise to a movement backwards and forwards between perception and recollection, a process which constitutes an experience of duration

- The ‘otherness’ or ‘indifference’ of the world which confronts us with our own absence (what Woolf calls ‘constitutive absence’, or the world without us)

- ‘Formlessness’ and the act of representation

<8>In discussing the composite images which make up ‘A Forest of Signs’, I have adopted the phrase ‘divided glance’, used by Woolf in her last novel Between the Acts, which refers to imaginative thought (or daydream) coinciding with visual perception in a simultaneous registering of the real and the imaginary. Woolf writes:

she felt on her face the divided glance that was half meant for a beast in a swamp, half for a maid in a print frock and white apron (8)

In the ‘divided glance’ that Mrs Swithin gives to Grace the maid, subjective fantasy and the external world (as well as nature and civilisation) occupy the same moment of perception. For my purpose, this phrase refers to the construction of the photographic composites in ‘A Forest of Signs’; central to the ‘divided glance’ in these images is the cut or break which both divides and unites elements of the natural world and urban architecture within the frame without attempting to camouflage this break. One image is grafted onto another. Further, it can be used to describe the pedestrian’s visual perspective on trees within the urban mosaic of the street.

<9>To begin with, how do we see as we walk? Here is Woolf’s description of the experience of urban street walking from her essay ‘Street Haunting : A London Adventure’ and how we see as we do so:

When the door shuts on us […] the shell like covering which our souls have excreted to house themselves, to make for themselves a shape distinct from others, is broken and there is left of all these wrinkles and roughnesses a central oyster of perceptiveness, an enormous eye. How beautiful a street is in winter! It is at once revealed and obscured […]. But after all, we are only gliding on the surface. The eye is not a miner, not a diver, not a seeker after buried treasure. It floats us smoothly down a stream; resting, pausing, the brain sleeps as it looks. (2)

<10>Vision is shaped by how we participate in the social space of the street; the eye may indeed float us along, but it also darts to and fro, responding to the flux of light and attentive to colour and movement in the field of vision. Our individual pace, crowds, the weather or time of day are some of the things which determine our rhythm of movement. If as streetwalker we decide to pause and photograph on the street, then purposeful observation breaks up the flow. The activity of the pedestrian street photographer is an embodied one; the scattered contingency of perception and event becomes consciously formalised – first through the physical point of view of the photographer, as a body amongst bodies, and secondly through the point of view of the camera. The fluidity of the travelling eye is arrested as an image is framed through the camera and the glancing moment comes to be spatialised as visual composition.

<11>The act of framing a scene or object through photography introduces a break, separating that which lies inside the frame from that which lies outside. The resulting image is always a fragment in relation to other fragments which are themselves open ended. Bernard in The Waves watches the mirror reflection of the hairdresser as his hair is cut and he meditates upon those of his generation cut down by another kind of cold steel:

withered and how soon forgotten! Upon which I saw an expression in the tail of the eye of the hairdresser, as if something interested him in the street. (693)

From one eye to another, Bernard’s noticing the distracted glance of the hairdresser onto the street outside, beyond his view, brings him back from a melancholy brooding upon death to the prosaic and inevitable change in everyday life:

Tuesday follows Monday: Wednesday, Tuesday. Each spreads the same ripple. The being grows rings, like a tree. Like a tree, leaves fall. (696)

This awareness of the world in constant motion (both the tree and the freneticism of the city), acknowledges a reality always going on beyond the frame of our immediate vision and beyond our ability to grasp it fully.

<12>Architecture frames the city in many different ways. The glass walls lining contemporary city streets, for example, allow us to look back behind us at the way we might have come. In the mirrored reflection we catch sight of the street from an oblique perspective, in a way which our everyday visual habits overlook. What we see is linked to the time of day, for the city has its routines of inhabitation; early in the morning, at night or the weekend, is the time of the dispossessed, street dwellers and the army of workers that maintain the city streets. Recording the reflected image, the camera sees what we might otherwise not see, and we see the trees, themselves witnesses to the unseen of the city.

<13>The street tree mediates between the passage of traffic and the buildings which line the street. On the threshold between entrance to internal space and exposure to public space, it shares this intermediate space with pedestrians. These trees often exceed our lifetime and can also outlive buildings so readily demolished through property speculation. Their existence may then draw attention to a dysfunctional architectural relic or pattern of streets now vanished. The city has its blind spots, curious empty corners, pockets of leftover space. The presence of such trees (often overlooked) stands between the abandoned architectural site and the meaningful social space, calling attention to the forgotten in our collective experience. In her essay ‘The Docks of London’, Woolf writes:

When suddenly, after acres and acres of this desolation one floats past an old stone house standing in a real field, with real trees growing in clumps, the sight is disconcerting. Can it be possible that there is earth, that there were once fields and crops beneath this desolation and disorder? Trees and fields seem to survive incongruously like a sample of another civilization among the wall-paper factories and soap factories that have stamped out old lawns and terraces. (194)

<14>As living things, trees are registers of seasonal and climate change, responsive to light, wind and temperature. They are marked by perpetual rubbing, abrading and scoring by people, objects, the elements, by what Woolf refers to as the ‘common life’ – a major preoccupation of her work. The composite photograph can draw attention to the co-presence of various traces of elemental weathering and the material effects of passing time. This attention to materiality as a measure of time features strongly in Woolf’s writing, as in Jacob’s Room:

The sun had already blistered the paint on the backs of the green chairs in Hyde Park; peeled the bark off the plane trees; and turned the earth to powder and to smooth yellow pebbles. Hyde Park was encircled, incessantly, by turning wheels. (228)

Human progress continually circles around itself, not moving forwards but echoing the turning of the seasons and the seasonal shedding of the plane tree.

<15>Incessant movement, ceaseless change; the common life on the street is a perpetual process of passing bodies, connecting gazes, crossings, recognitions and, equally, non-engagement, non-recognition. We pass along the street, fleetingly present, we do not endure. To stop for a while, linger and observe, to look and listen allows a mingling of interior to exterior in our sense experience of urban life. If we do this, we become aware that there are times on the street when a sudden hush descends, or the streets are emptied of human presence and the world is suddenly acutely visible as existing beyond us, without us:

Listless is the air in an empty room, just swelling the curtain; the flowers in the jar shift. One fibre in the wicker armchair creaks, though no one sits there […] Pickford’s van swung down the street. The omnibuses were locked at Mudie’s corner.[…] And then suddenly all the leaves seemed to raise themselves.

Jacob! Jacob! Cried Bonamy, standing by the window. The leaves sank down again. (247)

<16>Woolf most poignantly evokes absence in Jacob’s Room through the slight movements of inanimate objects in an empty room in contrast to the busyness of the street outside. The leaves of the tree outside suddenly rise as if enacting a last breath upon which the name of the departed floats, suspended. Time is held in the balance before the leaves sink down once more.

<17>There is an analogy here between how in the act of reading we connect the sequence of events described by Woolf above and how we are drawn to interpret a visual image over time. As the written sentences carry us backwards and forwards between interior and exterior, so doubling and repetition in photographic composition keeps the gaze moving and returning, backwards and forwards, activating the imperative to look again, to absorb and dwell in the image. The eye shifts, something has changed, but something remains the same. This restless leaving and returning of the gaze is a visual evocation of intertwined organic processes of thinking in looking, and looking in thinking, and of how perception, conscious and unconscious thought are interwoven in time.

<18>The singular nature of the street tree seems to arise from the paradox that its organic vitality is nevertheless rooted to the spot. It exists as an entity planted in a landscape of our making and like us it lives and changes, but the tree draws from and expands into the space around it whilst remaining relatively immobile. This grounded constancy gives the tree an autonomy in which it seems to stand apart, oblivious to our transient existence:

In Spring, the garden urns, casually filled with windblown plants, were gay as ever. Violets came, and daffodils. But the stillness and the brightness of the day were as strange as the chaos and tumult of night, with the trees standing there, and the flowers standing there, looking before them, looking up, yet beholding nothing, eyeless and so terrible. (To the Lighthouse 368)

Not only are the trees and flowers blind to our being, they will go on after we are gone. Woolf uses the figure of the tree as a motif for metaphysical enquiry elsewhere, pursuing this meditation not only upon the possibility of a world indifferent to us, but also one existing without our consciousness of it. In The Years, she writes:

She had been thinking, Am I that, or am I this? Are we one, or are we separate-something of the kind.

‘Then what about trees and colours?’ she said, turning round.

‘Trees and colours?’ Sara repeated.

‘Would there be trees if we didn’t see them?’ said Maggie. ‘What’s “I”?’ (120)

<19>The world is strange, unruly and indifferent to our presence. And here the photograph exposes this ineradicable difference, organising elements in the visual plane such that we can grasp a relationship between ourselves and the world and we know we exist through this dialogue. It is as photograph that the image of the tree looks back at us confirming our being. Made into an image, it is no longer alien.

<20>Many of Woolf’s characters are themselves urban dwellers, often in movement, filtering their thoughts and feelings through an immersed experience of the city. A particular place may be intimately tied to a thought in passing, leading to a constitution of self which is open to the transience of the elements, a self which is itself elemental and metamorphosing, chrysalis-like:

Then he got up and went; we all got up; we all went. But I pausing, looked at the tree, and as I looked in Autumn at the fiery and yellow branches, some sediment formed; I formed; a drop fell; I fell – that is, from some completed experience I had emerged. (The Waves 669)

<21>Trees are deeply rooted in Woolf’s writing as metaphor for the self – as an elaboration of the porous boundary between the human and non-human elements, and as metaphor for the wandering patterns of an organic mind, ceaselessly seeking order out of chaos through language. She writes:

the mind grows rings; the identity becomes robust; pain is absorbed in growth. (The Waves 673)

<22>Trees can figure as images of inner revitalisation, but once the shutter of the eye opens onto the world (a photographic analogy familiar to Woolf) the exposed external otherness of trees constitutes a limit, the visual evidence of the tree in the world evoking distance and separation:

Where did thought begin?

In the feet? she asked. […] She closed her eyes. Then against her will something in her hardened. It was impossible to act thought. She became something; a root; lying sunk in the earth; veins seemed to thread the cold mass; the tree put forth branches, the branches had leaves. ‘– the sun shines through the leaves,’ she said, waggling her finger. She opened her eyes in order to verify the sun on the leaves and saw the actual tree standing out there in the garden. Far from being dappled with sunlight, it had no leaves at all. She felt for a moment as if she had been contradicted. For the tree was black, dead black. (The Years 114)

<23>At other times, the tree is brought into play to evoke psychic and physical disintegration. In Mrs Dalloway, Septimus’ shell-shocked derangement leads to a break down of boundaries between the self and the world:

But they beckoned; leaves were alive; trees were alive. And the leaves being connected by millions of fibres with his own body, there on the seat, fanned it up and down; when the branch stretched, he too, made that statement. (26)

<24>There is also organic dissolution constantly beckoning:

But afterlife, the slow pulling down of thick green stalks so that the cup of the flower, as it turns over, deluges one with purple and red light. Why, after all, should one not be born there as one is born here, helpless, speechless, unable to focus ones eyesight, groping at the roots of the grass, at the toes of the Giants? As for saying which are trees, and which are men and women, or whether there are such things, that one wont be in a condition to do for fifty years or so. There will be nothing but spaces of light and dark, intersected by thick stalks and rather higher up perhaps, rose shaped blots of an indistinct colour – dim pinks and blues – which will, as time goes on, become more definite, become – I don’t know what. (‘The Mark on the Wall’ 780)

<25>The threat of formlessness and disintegration is both articulated and resolved through the act of writing or photographing. And once more the image of trees play a vital part in making sense of experience which threatens to overwhelm:

It is the effort and the struggle, it is the perpetual warfare, it is the shattering and piecing together – this is the daily battle, defeat or victory, the absorbing pursuit. The trees scattered, put on order; the thick green of the leaves thinned itself to a dancing light. I netted them under with a sudden phrase. I retrieved them from formlessness with words. (The Waves 684)

<26>Towards the end of The Waves, Woolf writes:

‘A weight has dropped into the night,’ said Rhoda, ‘dragging it down. Every tree is big with a shadow which is not the shadow of the tree behind it. (605)

One might read this enigmatic statement as a felt weight of darkness which falls like a pall over the present, but I would suggest that in these words Woolf summons up a shadow cast by a tree which falls not from behind but emanates from the future, foreshadowing the present. Just as Woolf’s writings from the past have come to shadow my activity of photographing trees, so these same trees of central London for Woolf would have represented a living present which contained implicitly within them a future. Photographing or writing of trees within this city, which is changing as I change, establishes a multiplicity of connections, of possible pasts and futures within what Woolf calls the ‘common life’. To do so establishes a way of dwelling in the city in which it writes me as I write it, and in which the project of photographing trees in public spaces inscribes the elusive private dream within the common collective dream as ‘a forest of signs’:

And all the lives we ever lived

And all the lives to be,

Are full of trees and changing leaves. (To the Lighthouse 351)

All images © Susan Trangmar 2012

Works Cited

Woolf, Virginia. Between the Acts. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press, 1998.

—. ‘The Docks of London’ in Selected Essays. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press, 2009.

—. Jacob’s Room. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press, 2008.

—. ‘The Mark On The Wall’ in A Haunted House: The Complete Shorter Fiction. London: Vintage Books, 2003.

—. Mrs Dalloway. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1992.

—. Street Haunting: A London Adventure. Harmondsworth: Pocket Penguin, 2005.

—. The Waves. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1992.

—. To The Lighthouse. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1992.

—. The Years. London: Vintage Books, 2004

To Cite This Article:

Susan Trangmar, ‘“A Divided Glance”: A Dialogue Between the Photographic Project ‘A Forest of Signs’ and the Figure of the Tree in Virginia Woolf’s Writing’. The Literary London Journal, Volume 10 Number 1 (Spring 2013). Online at http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/spring2013/trangmar.html. Accessed on [date of access].