Madhu Singh

The year was 1935, and India was struggling to break free after almost two centuries of British domination. Indian nationalism of various hues had charged the imagination of the elites and the masses alike. Ideas of socialism and revolution were in the air. Influenced by Marxism and inspired by the success of the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, writers in India were shifting their earlier Gandhian stance in favour of a more revolutionary ideology.

Strong nationalist feelings had begun to emerge in literature, reflecting – according to the Urdu scholar and communist Ralph Russell – an empathy for the poor and a questioning of existing customs as well as desire for liberation from foreign rule and indigenous elites. The novels written during this momentous period in Indian nationalism played an important role in imagining and embodying the radical vision of anti-colonial nationalism, though the ‘nation-centredness’ of this new generation of Indian novelists was tempered by a cosmopolitan outlook and experience.

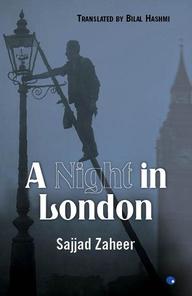

Located at this moment in literature and politics was Sajjad Zaheer’s Urdu novel London ki Ek Raat [A Night in London], written in1935 and first published three years later. It depicted the angst of the young men (and the underground gentlemen revolutionaries) who, angered by repressive British policies in India, engaged in anti-imperialist activities while in London. In this heyday of Indian nationalism, London had become ‘a hot bed of radical anti-colonial activity’(Ranasinha 2007).

Located at this moment in literature and politics was Sajjad Zaheer’s Urdu novel London ki Ek Raat [A Night in London], written in1935 and first published three years later. It depicted the angst of the young men (and the underground gentlemen revolutionaries) who, angered by repressive British policies in India, engaged in anti-imperialist activities while in London. In this heyday of Indian nationalism, London had become ‘a hot bed of radical anti-colonial activity’(Ranasinha 2007).

Not all the young men who arrived in London were politically charged. Many preferred to spend their time in leisurely pursuits and often stayed back in Britain for unreasonably long periods. Quite a few of them, as depicted in this novel, studied for the Indian Civil Service examinations with dreams of being collectors or magistrates of some province back home.

From the 1870s, universities such as Oxford and Cambridge had begun to admit Indian students. Some became, in Kipling’s mocking phrase, more English than English, while others arrived at a stage of political awakening and alienation through which they became articulate and ardent champions of Indian freedom (Trivedi 2007). Besides being a centre of their educational aspirations, London (and Paris, too) had become known for its vibrant cosmopolitan and intellectual culture.

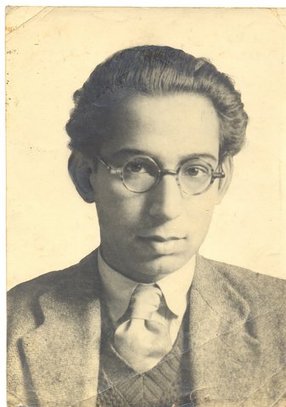

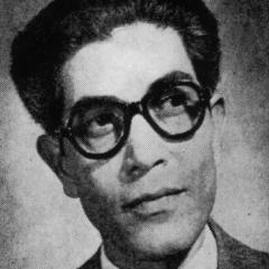

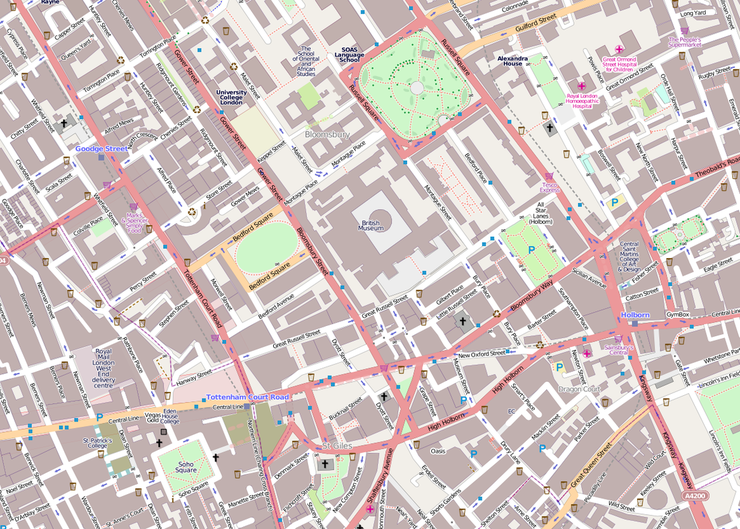

Born into an upper class family of Lucknow in 1905, Sajjad Zaheer, was one of the pioneers of the Progressive Writers’ Movement in India – a movement which dates from a meeting in November 1934 at the Nanking Restaurant in Denmark Street, close to both Bloomsbury and Soho. He spent almost a decade in Britain, gaining a master’s degree at Oxford and then embarking on a career in law at Lincoln’s Inn. All this was amid the furore caused by the publication in 1935 of a collection of short stories, Angare [Burning Embers]. Zaheer had co-authored this volume with his friends Ahmed Ali, Rashid Jahan, and Mahmudulzafar. The book was banned by the United Provinces state government in India for having ‘hurt the religious susceptibilities of a section of the community’. Dubbed inflammatory in nature, Angare was a critique of the culture and community from which the authors’ sprang and of Indian society in general.

In London, Sajjad Zaheer came into contact with several leftist writers and intellectuals and was influenced by socialist thought. London ki Ek Raat was Zaheer’s second work of fiction, a novelette of a hundred and fifty pages, and was written in Urdu in spite of his English education and his grounding in European literary traditions. It was an experiment in fiction writing that adopted a variety of avant garde European styles and techniques and was also the first novel to display the ideologies and aspirations of Indian youth in the political context of India.

In his foreword to the novel, Sajjad Zaheer modestly stated:

This book can hardly be called a novel or a story. If you wish to see one aspect of the life of Indian students in Europe you may read it. The greater part of it was written in London and Paris, and on the ship returning to India. That was more than two years ago. Now when I read through the manuscript I hesitate to send it to the printer. (Russell)

Written under the influence of James Joyce’s Ulysses and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, it captured – as the title suggests – the events of a single evening in London. On a broader level, it recreated the life of Indian students in London who spent time in cafes and coffee houses in and around the Bloomsbury area, smoked cigarettes, discussed Marxism and socialism, criticised British imperialism, condemned racism, entered into affairs with white girls and lived lavishly on money sent to them by their affluent families back home.

The novel opens on a cold and foggy evening in the London of the 1930s. Thick fog envelops everything like a wet blanket, making breathing difficult. The streets are dim, street lights struggle hard with the darkness which is fast approaching. Despite the cold, the roads are jammed with motor cars, lorries and buses and people hurriedly returning home from offices and factories.

The Bloomsbury area is abuzz with students and intellectuals, artists and poets and visitors from all over. The clock says it’s ten past six in the evening. At Russell Square underground station, Azam waits for his girlfriend, Jane, who has promised to come but hasn’t. Newspaper vendors shout headlines: ‘Jobless Workers Assemble at Hyde Park’, ‘Ten British Soldiers Stop Ten Thousand “Natives” from Violence’, ‘A British Soldier Hurt and Fifteen Natives Die’ … . Distressed at the plight of Indians (natives!) back home, his mind strays towards his country.

His thoughts are soon interrupted as his friend Rao, a law student, walks out of the station. Both head towards the local pub for a glass of beer before making it to the party hosted by their friend Naim ud din who is pursuing a PhD. At the pub they encounter the conflicting nature of the public’s response to India: the unequivocal support to the cause of freedom by a couple of British factory workers and also a drunkard’s arrogance and racism towards Indians seen in the derogatory remarks made towards Gandhi.

At Naim’s party , the gramophone plays loud music and young men and women dance to its tune. Over innumerable glasses of wine and lemonade, cups of tea and coffee, and amid spirals of cigarette smoke, heated discussions cover a variety of topics ranging from women’s freedom in European societies compared to the status of Indian women, alienation from one’s culture and tradition among the Indians living in England, the gradual decline of British imperialism, anti-colonial and anti-imperial nationalism and resistance, socialist revolution and communism. Ideological differences become evident and scores are pursued through lively argument.

All the while, the host Naim finds convivial company in an English woman, Sheila Green, and falls deeply in love with her. It is their first meeting. Much to his anguish, Sheila Green confides her love and admiration for her Indian friend and lover, Hiren Pal, a final year medical student who left for India eighteen months previously to fulfil his commitment towards his motherland. She has lost contact with him and is heartbroken. Soon after the loud music, dancing and brawling is interrupted by an angry landlady and the party disperses.

In the second part of the novel, while the guests depart Sheila Green stays back at Naim’s request. Through long flashbacks into her past, Naim – and the readers – become acquainted with a long and passionately romantic prequel to her story, of the time she and Hiren spent together in a small Swiss village. This is quite different in tone to the first part of the novel and is apparently autobiographical in nature. As Sheila’s story comes to an end, Naim tries to console her. Then, as morning approaches, she puts on her hat and coat and says goodbye to her host. Naim returns to his armchair and sits there motionless. ‘The fire had gone right out, and the room was getting colder and colder. The watery light of morning like a thief on tiptoe, began to steal in through the window’ (Russell 258).

Sajjad Zaheer’s son-in-law and biographer has suggested Zaheer, while in London, did indeed develop an interest in a young lady and has suggested that he based the character of Hiren Pal on his own experience. As with Hiren, Sajjad Zaheer too was influenced by Marxist and socialist teachings. For young radical nationalists like Hiren – and Zaheer – idealism was not ‘an indifference to material things, the religious life, devotion to God, but the fight in this world against greed lust and the power to oppress and tyrannize over others, the fight against ignorance and stupidity and deceit, the fight to awaken the sleeping melodies which a man cannot hear unless he has a generous heart and an alert mind and a healthy body’. The latter part of the novel is significant in its use of modernist techniques of stream of consciousness and interior monologue in Sheila Green’s romantic flashbacks of her passionate relationship in Switzerland. It also focusses on Hiren’s deep rooted commitment to the nationalist cause which even his love for Sheila could not diminish. His mission in life transcended his love for her, for he believed that the there were things in his life more important than love.

This novelette remained very controversial in the eyes of its critics. Sajjad Zaheer’s one time friend, Ahmed Ali – the only writer in the true sense of the term among the Progressive Writers’ Association – disparagingly opined that London ki Ek Raat was ‘an unsuccessful attempt at a novel’ because of its ‘romantic predisposition’. Sajjad Zaheer, he says ‘discredits his own credo of a Marxist line in Progressivism’ (Ali 1974). On the other hand, critics like Syed Ehtesham viewed it favourably, stating that despite its limited canvas, it addressed the anguish and restlessness of youth living in India or in England not to be found in any other contemporary novel. Ralph Russell, too, considered this novel as ‘a good book viewed simply as literature, with realistic characterization, convincing dialogues and vivid descriptive power’.

London ki Ek Raat can be seen as one of the earliest examples of anti-colonial, anti–imperialist nationalist writing. At the core of the novel lies a deep ideological thought process that aimed at social transformation and national liberation. Hiren’s passionate critique of the Indian society at large is an appropriate example of this spirit:

When a nation is enslaved, when eighty percent of its people cannot get enough to eat, when sickness and disease and epidemic are so rife that a really healthy man is hard to find, where education is confined to handful of people, where even children look like faded flowers, where in most faces you can read hunger, starvation, poverty, distress, idleness, stupidity , ignorance—and in the rest a repulsive sort of prosperity—in such a country to look for idealism would be the height of stupidity.

Sajjad Zaheer’s London navigated between ‘the houses of European modernism and his burgeoning political radicalism’ and forged ‘a global transnational vision’ and may be remembered for its radical departure from the then current trends in Urdu literature.

London ki Ek Raat is also, however, a truly autobiographical novel. Sajjad Zaheer’s son-in-law, Ali Baqar, recounts that while visiting London with Zaheer, he had the opportunity to meet the real Sheila Green. And she looked as beautiful as she is described in the novel. It brings to mind the famous lines written by Zaheer’s close friend, the well known Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz:

Aur bhi hain gham zamane mein mohabbat ke siva

Raahatein aur bhi hain vasl ki raahat ke siva

Mujh se pehli si mohabbat mere mehboob na maang.(There are other sufferings in the world besides love,

There are other pleasures besides the pleasures of union.

Do not ask from me, my love, for that love again.)

London ki Ek Raat has been published for the first time in an English translation, as A Night in London. The translator is Bilal Hashmi. A partial translation by the Urdu scholar Ralph Russell is available online.

Dr Madhu Singh is Associate Professor in the Department of English and Modern European Languages at the University of Lucknow.

Works Cited and Consulted

Ali, Ahmed – ‘The Progressive Writers’ Movement and the Creative Writers in Urdu’ in Marxist Influences and South Asian Literature, ed. Carlo Coppola Michigan: Michigan State University, 1974

Ahmad, Talat – Literature and Politics in the Age of Nationalism: The Progressive Writers Movement in South Asia, 1932-56, New Delhi: Routledge, 2009

Baqar, Ali – Roshni ka Safar: Sajjad Zaheer, New Delhi: Saransh Prakashan, 2000.

Coppola, Carlo – ‘The Angare Group: The Enfant Terribles of Urdu Literature’, Annual of Urdu Studies, 1981

Rais, Qamar – Sajjad Zaheer, New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2008.

Ranasinha, Ruvani – South Asian Writers in the Twentieth Century Britain: Culture in Translation, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2007

Russell, Ralph – How Not to Write the History of Urdu Literature, and Other Essays on Urdu and Islam, Delhi; New York: Oxford University Press, 1999

——- ‘Sajjad Zaheer: A Selection from Landan ki Ek Raat’, Annual of Urdu Studies

Silvestri, Michael – ‘The Sinn Fein of India’: Irish Nationalism and the Policing of Revolutionary Terrorism in Bengal’, Journal of British Studies, 39/4, 2000, pp.454-486.

Trivedi , Harish – ‘Colonial Influence, Postcolonial Intertextuality: Western Literature and Indian Literature’, Forum for Modern Language Studies, 43/2, 2007, pp.121-133

Zaheer, S Sajjad – London ki Ek Raat. Roshni ka Safar: Sajjad Zaheer, ed. Ali Baqar, New

Delhi: Saransh Prakashan, 2000

All rights to the text remain with the author.