Susie Thomas

Xiaolu Guo’s first novel in English has a chronological structure: the protagonist’s visa is for one year only, so the migrant meter starts ticking from the moment she lands in Heathrow from Beijing. As the title suggests, A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers is concerned with language, and the narrator’s attempt to make herself understood as she finds her way around the city. Although it isn’t arranged alphabetically, it is divided into dictionary entries of key words, beginning with initial impressions: typically she notes the English obsession with the weather, the strangeness of the food and the contrast between her expectation of London (‘should be like Emperor’s city’) and the ‘tacky reality’.

Like many new to the city before her she is lost: ‘How I finding important places including Buckingham Palace or Big Stupid Clock?’ The narrator soon realises that nobody in England can be bothered to learn how to pronounce her name ‘properly’ (a term she struggles to comprehend). So, she calls herself Z, and comes to be called Z. Later entries reflect the philosophical changes Z undergoes as she considers the meaning of ‘self’, ‘identity’, ‘freedom’ and ‘isolation’. She begins to question western concepts: how can they value both ‘privacy’ and ‘intimacy’ at the same time? The gain in knowledge and sophistication is also felt as a loss of innocence and spontaneity.

Above all, A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers is an A-Z of London. There are no monuments, after the briefly entertained and soon abandoned attempt to go to Westminster. There are no pilgrimages to Chinatown and only one visit to a Chinese restaurant, which ends in embarrassment. Despite this, the novel is a love letter to London, as the place where Z becomes an artist. Her epiphanies take place in greasy spoons, pubs, and in Hackney public library.

Nuttington House in Brown Street

The hostel where Z is booked to stay on her arrival is ‘prison looking’.

Sixteen pounds for per bed per day. With sixteen pounds, I live in top hotel in China with private bathroom. Now I must learn counting the money and being mean to myself and others. Gosh.

She looks for a cheap flat on LOOT. But all the flats are ‘dirty and damp and smelly’. She thinks that London is a ‘refugee camp’.

Holborn

Holborn. First day studying my language school. Very frustrating.

And the more she learns the worse it gets. Why does English grammar privilege the individual over the place? Why do they have tenses?

Hyde Park

On her way back to the hostel after her first language class, Z loses her way and gets caught up in the Stop the War march of 2003: ‘Many smiles. They feel happy in sunshine.’

She looks at the biggest demonstration in postwar British history through the lens of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book.

A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture… A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence.

She wonders what the demonstrators expect to achieve with their pleasant day out: ‘if people here want to against war in Iraq, they needing have civil war with their Tony Blair’.

Tottenham Hale

Z’s first lodging in London is a kind of halfway house:

House is two floors, lived by Cantonese family: housewife, husband who works as chef in Chinatown, and 16-year-old-British-accent son.

Z only speaks Mandarin so there isn’t much communication between her and the host family.Everything inside the house is traditional and not much fun: they work all the time and nothing grows in the back garden, which is covered in concrete. It is as if they don’t want to put down roots.

Z doesn’t feel at home there and she is intimidated by the locals:

Every night I coming out Tottenham Hale tube station and walking home shivering. I scared to pass each single dark corner. In the place, crazy mans or sporty kids throwing stones to you or shouting to you without reasons. Also, the robbers robbing the peoples even poorer than them. In China we believe “rob the rich to feed the poor”. But robbers here have no poetry.

Cine-Lumiere, South Kensington

Guo is a filmmaker as well as a novelist, so perhaps it is no surprise that her heroine wants to go to the flicks. She meets the man who becomes her lover after a screening of Fassbinder’s Fear Eats the Soul, about the love affair between a Moroccan immigrant worker and an older German widow. She thinks: ‘A man in this country save me, take me, adopt me, be my family, be my home’. How wrong can she be?

Kew Gardens

Their first date is in Kew Gardens, which Z loves, at first: ‘lotuses and bamboos is growing in India garden, plum trees and stone bridge is growing in Japanese garden. Where is my Chinese garden?’

She moves in with her lover as the result of a misunderstanding:

‘I want see where you live,’ I say.

You look in my eyes. ‘Be my guest.’

Our long-shabby Hackney Road

His house is old, ‘standing lonely between ugly new buildings for poor people’. But at the back there is a little garden: ‘the noisy London being stopped by brick wall…. Plants and sculptures on sunshine.’

Z attributes much of her new vocabulary to her lover’s teaching. He is an anarchist, and a sculptor of the human body; a bisexual drifter who is twenty years older than she is. The lover, directly addressed as ‘you’ throughout the novel, remains unnamed, suggesting her ambivalent feelings. Z tells us that Anon is her favourite poet and the book is prefaced by the disclaimer: ‘Nothing in this book is true, except for the love between her and him’. But rendering the lover anonymous also seems like an attempt to efface him. His anonymity is particularly ironic, given that Z so often conceives of their relationship as an antithesis between her Chinese value of the ‘collective’ and ‘the group’ against his Western individualism and belief in the ‘self’.

Chop Chop Hackney

Z starts to belong in Hackney. She doesn’t feel homesick for China: above all, she is glad to have escaped her domineering mother, who told her that she was an ugly peasant girl whom nobody would want to marry. But she does miss Chinese cooking and one evening she takes her lover out to eat.

Restaurant has very plain looking. White plastic table and plastic chairs and white fluorescent lamp. Just like normal government work unit in China…. I swear I never been so rude Chinese restaurant in my entirely life. Why Chinese people becoming so mean in the West?

Brick Lane Market

The only problem between the couple is food: he is a vegetarian and she is an avid carnivore, who was always hungry as child growing up in a poor town in South China. On Sundays she wants to shop in the supermarket but he isn’t keen: “Hmm, right. Let’s worship in Sainsbury’s every Sunday”.

You take me to Brick Lane market. It is really a rubbish market. All kind of second-hand or third-hand radios, old CDs, used furniture, broken television set … I wonder if all these things made in China.

You walk in the rubbish market with your old brown leather jacket and your dirty old leather shoes…. But you look great with these rubbish costumes in the rubbish market.

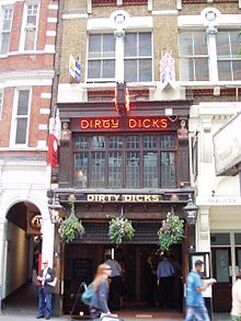

Dirty Dick’s, Liverpool Street

While her lover is away for a few days, Z decides to visit an English pub.

I sit in pub alone, trying to feel involving in the conversation. It seem place of middle-aged-mans-culture. … While I sitting here, many singles, desperately mans coming up saying, “Hello darling”. But I not your darling. … Some is drinking huge pint Lager, is like pee.

A young man buy me beer. He is the only good looking one.

I say: “ I feel so delightful drinking with you. Your face and words are very noble”.

The man surprised and happy. He stops his drinking.

“Noble, eh?”

A while. He say: “Love, you only think my words are noble because I can speak English properly – …but it is my mother tongue”.

Columbia Road Flower Market

Z’s favourite place is Columbia Road flower market, where her lover takes her so she can plant a little Chinese garden in Hackney.

We brought the small little sprouts of Chinese cabbage at home. Eight little sprouts all together. … We watering Chinese cabbage sprouts every morning, loyal and faithful, like every morning we never forgetting brushing our teeth. Seeing tiny sprouts come out, my heart feel happy. Is our love. We plant it.

Seven Seas, Hackney

Z discovers her own language in a greasy spoon, run by a Cypriot cooking full English breakfasts.

I love these oily oily café around Hackney. Because you can see the smokes and steams coming out from the coffee machine or kitchen all day long. That means life is being blessed.

She reads a headline in the newspaper: ‘Lost For Words -– The Language of an Endangered Species’ about the death of the last speaker of womans-only language, Nushu, ‘the language used by Chinese women to express their innermost feelings’. Z thinks: ‘Maybe this notebook which I use for putting new English vocabularies is a Nushu’; this becomes, of course, The Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers that we read.

Between Brick Lane and Bethnal Green Road

Z’s lover finds his own family heavy going and he doesn’t want to have any kids himself. But he takes her to visit an old Bengali mother and her ten children:

Is big three-floor house with ten little rooms. Five childrens are from same mother, and another five childrens are from another woman but with same man.

The father is dead but they all just get on with their life. Z doesn’t understand how a mother can raise ten children without a husband.The Bengali mother can’t speak English but she teaches Z how to be independent.

Unlike Fassbinder’s film, there is little prejudice against Z amongst the community in Hackney. The fear that eats the soul results from her insecurity: ‘The fear of without home. Maybe that why I love you? I am building the Great Wall around you and me because I am too scared to lose the home. I have been living in that big fear since my childhood’.

Berwick Street

At first, Z feels shame about sex: ‘Is such taboo in China. I never really know what is sex before. Now I naked everyday in the house, and I can see clearly my desire.’ It is the lover’s language that seduces her: ‘I think you are a noble man with noble words’ (Has she been to the pub?) She tells him: ‘I want learn most beautiful English words because you are beautiful’. The erotic and the linguistic are closely paralleled: she learns about tenses, pronouns and plurals through reading porno mags, the instructions on a packet of condoms, and the box of a vibrator.But the discovery of her desire is also felt as a threat to her independence: ‘My whole body is your colony’. At this point, Z decides to educate herself in westernism and goes to a peepshow.

Soho, Berwick Street. My feet can’t move away from a sex shop. Some leather bras with two hole in middle, some leather belt, some handcuff…

Z is so mesmerised she goes back another day and pays twenty pounds to see a live show. ‘While I am standing there watching, I desire become prostitute. … To take my body away from dictionary and grammar and sentences’. She resents her lover’s power over her, just as she resents being colonised by the English language.

Rupert Street

But Z’s lover introduces her to a lot of good stuff: Frida Kahlo, Hanif Kureishi, Virginia Woolf, Bette Midler. One night he takes her to a little cinema on Rupert Street:

You take me watch documentary films double bill. Two crazy women in one night.

The first film is about Mae West: ‘an extremely successful Hollywood star, always make audiences happy and laughing.’ The second film is Billie on Billie: ‘She is extremely sad face, hopeless expression. From the film I learned her struggled by childhood, her prostitution mother, her sex abuse when she twelve years old, her drug and alcohol, her poor dignity being a black. …. A strange fruit. I want leave the cinema to cry. I feel her pain in my heart.’

She wants to become ‘Mae West, be her courage, her bravery, her humour, her creativity, her challenge to the world’ but fears she is ‘not even painful Billie. I am just obscure nobody with name starts from Z’.

Hackney Town Hall Library

Z’s lightbulb moment occurs when she reads Gustave Flaubert on the Greeks devoting themselves to art without even knowing where the next day’s bread might come from: ‘Let us be Greeks!’ She decides to dedicate her life to something serious, not just making shoes like her parents.

I’d like to write about you, one day. I’d like to write about this country. People say one should separate one’s real life from one’s art work… So one can has less pain, and be able to see the world soberly. But I think this is very selfish attitude. I like what Flaubert said about Greeks. If you are a real artist, everything in your life is part of your art.

South Kensington again

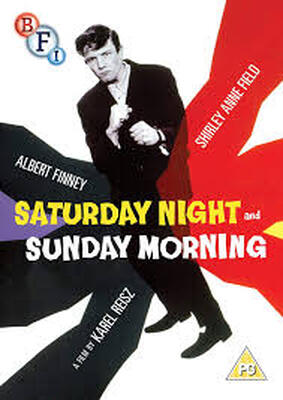

The last film they watch is Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Z sees her lover in Albert Finney’s frustrated, restless character and she identifies with the young woman who desperately wants a home. Their relationship is bookended by movies.

It is only towards the end of the novel that she asserts her cultural independence, telling him: ‘“You never really pay attention to my culture. You English once took over Hong Kong, so you probably heard that we Chinese have 5,000 years of the greatest human civilization ever existed in the world … Our Chinese invented paper so your Shakespeare can write two thousand years later. Our Chinese invented gunpowder for you English and Americans to bomb Iraq”’. Her lover stares at her and has ‘no words’.

Back in Beijing

In the epilogue Z calls her mother from Beijing to say that she is not coming home to their small town. Her mother is furious and Z thinks: ‘Sometimes I wish I could kill her. Her power control, for ever, is just like this country.’

Even in Beijing Z feels out of place: ‘everybody talks about buying cars and houses, investing in new products…. I can’t join in their conversations.’

She is homesick for London: ‘where I had my most confused days and my greatest passion and my brief happiness and my quiet sadness.’

Biographical readings of A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers could be reductive: this carefully structured novel, with its web of allusions, is not a collection of diary jottings but a work of art. Guo has written many novels, made films, taught in New York, Paris and Berlin; and lives with her husband and daughter in Hackney.

Susie Thomas has written about British authors from Aphra Behn to ER Braithwaite. Her most recent volume is So We Live: The Novels of Alexander Baron, which she co-edited with Andrew Whitehead and Ken Worpole.

All rights to the text remain with the author.