Jonathon Green

The author William Pett Ridge, born a Kentish station-master’s son in 1859, arrived in London in 1880. There he worked as a railway clerk, while attending evening classes at what would be today’s Birkbeck College. Ten years later he published his first paid work, sketches of life in London for the St James Gazette. Presumably for fear of his more regular income, he signed his pieces ‘Warwick Simpson’. His first novel, A Clever Wife, appeared in 1895. The editor of the Bookman, Arthur St John Adcock, acknowledged that the novel ‘made more stir than most first novels do’ but thereafter the reviewers seem to have ignored him.

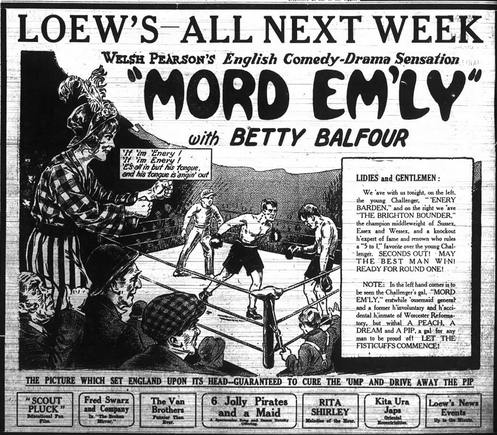

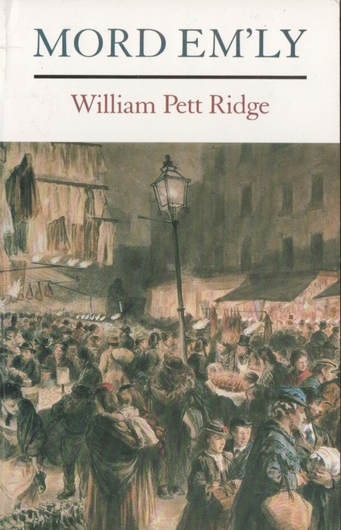

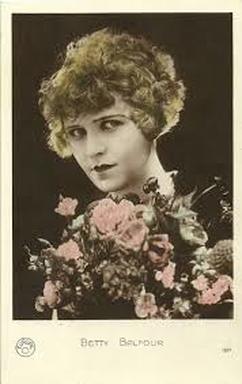

Only in 1898, with his fifth novel, Mord Em’ly, came popular success and his first best-seller. Pett Ridge must have been fond of this breakthrough hit. In 1922 he presented a miniature edition to the still recently created Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House, given to Her Majesty by a grateful nation. It was some 4.4 cm x 0.7 cm, bound in red morocco with gilt lettering on its spine and the royal monogram on its front; E.H. Shepherd, illustrator of Winnie the Pooh, produced a suitably sized bookplate. The library also contained four Bibles, a Shakespeare and 200-plus editions of contemporary British literature. In the same year the book was screened as a silent movie. It starred Betty Balfour, who appeared on the billboards as ‘Britain’s Queen of happiness’ and ‘The British Mary Pickford’. Abandoning the print edition’s Cockney phonetics, it was called Maud Emily, though the re-release preferred Me and My Gal.

Pett Ridge, like Ms Balfour a celebrity who is effectively forgotten today, was an undoubted success at the time, but his genre of writing might not have been automatically associated with royalty. Alongside such as Arthur Morrison, author of Tales of Mean Streets (1896) and A Child of the Jago (1894), Pett Ridge (1859–1930) was bracketed with the ‘Cockney novelists’, those authors, not necessarily East Enders themselves, who wrote of the tough but often unvanquished lives of those who were, and who, were one to be cynical, added a literary gloss to the popular west End pursuit of slumming.

Pett Ridge, like Ms Balfour a celebrity who is effectively forgotten today, was an undoubted success at the time, but his genre of writing might not have been automatically associated with royalty. Alongside such as Arthur Morrison, author of Tales of Mean Streets (1896) and A Child of the Jago (1894), Pett Ridge (1859–1930) was bracketed with the ‘Cockney novelists’, those authors, not necessarily East Enders themselves, who wrote of the tough but often unvanquished lives of those who were, and who, were one to be cynical, added a literary gloss to the popular west End pursuit of slumming.

But where several of his contemporaries, Morrison perhaps the most pessimistic, made you reach for the carving knife (assuming you had yet to pawn it or hadn’t already left it buried between the drink-sodden shoulder-blades of some other wretched sociopath and very likely one’s husband), Pett Ridge went for laughs. A humourist. His portraits – a somewhat dandified young man, all centre-parting, bow tie and braid-trimmed velvet jacket – might not make it obvious, but that was his reputation. The Times obit regretted his ‘kindly presence and never-failing humour’; he bantered with a visiting Mark Twain (introduced to the great man as ‘the Mark Twain of England’, he swiftly made a correction: ‘What he meant to say was that you are the Pett Ridge of America’), he was clubbable (J.M. Barrie nominated him for the Garrick), he did after-dinner speeches to the joy of all. He wrote sixty-plus books and two memoirs. His gravestone declares him ‘novelist and friend of the Cockneys’. It was all a long way from his beginnings: a guinea-a-week clerk for the railways.

Back on the mean streets the laughs were rare and probably malicious, but not in Pett Ridge’s fantasies. If anyone created the myth of the chirpy cockney sparrer it was he. And none chirpier than Mord Em’ly. The word feisty had been coined a few years earlier; it was just in time. It comes from the obsolete English fist, a small dog, yappy, snappy and bounding with energy, with an underpinning of dialect feist, to strut about, to flirt or show off. Mord was all that. And then some.

She wasn’t, in fact, a cockney proper – her home turf was The Cut, near Waterloo and the Old Vic and thus just south of the Thames – but for her creator’s purposes she might as well have been. Mord is of course poor, her mother a nervous wreck and her father (whom mother pretends is dead) ‘away’ (i.e. in prison) but if she runs in the streets as the junior member of the all-girl Gilliken Gang, there is no malice let alone hard-core criminality in her. Nor in the gang whose leader subsequently joins the Salvation Army. They harass the local boys but the violence is verbal – and witty – rather than physical. We are not talking Crips or Bloods. Nor even the Forty Elephants, a notorious and long-lived all-girl gang of south London shoplifters – the ‘Elephants’ referred to their base; the Elephant and Castle. Still, a girl gang in 1898… Dicky Perrott ‘The Child of the Jago’ in Morrison’s eponymous novel sees crime as an escape from wretchedness, but Mord Em’ly, a Naughty Nineties Cyndi Lauper, is above all out for fun, enjoying life, and giving as good, if not better than she gets:

‘How old might you be?’ ‘I might be a ‘undred and forty-nine,’ said Mord Em’ly … ‘I am jest close upon thirteen.’

Mord’s world is gentler than that of the Jago (in real life Old Nichol Street, just off Brick Lane, and notorious as one of the most violent and impoverished roads in London), and her slang reflects it. Mord Em’ly offers 48 examples of slang and A Child of the Jago 120. There are no overlaps. Pett Ridge’s slang is, as it were, of the open air, the friendly if bantering chat and the daylight; Morrison’s of the back room, the surreptitious, guarded plot and the night.

There is none of Dicky Perrott’s gutter cant in such words and phrases as act the giddy goat, soft (a weakling), slope off or scoot, song and dance (a fuss), bit of all-right, stony (broke), bounder, old baggage, put up one’s dooks (i.e. fists), give someone what-for, get the hump and the once-familiar query how’s the enemy? i.e. ‘what’s the time?’ It often appears as interjections: cheese it!, give over!, drop it!, buck up!, I don’t think, s’elp me greens!, language! Mord likes a vivid image: someone has ‘a face on ’im like half-past six’. Such ‘soft’ slanging is not there to represent some idea of femininity, and thus ‘weakness’ – her verbal sophistication can outwit virtually every male she meets – but her essentially ‘civilian’ status. Her jailbird father, a pitiful figure whose return home is greeted with anything but enthusiasm by our heroine, would have used a very different vocabulary.

Language and what modernity terms attitude make her indomitable. She is poor, working class, she lives that life, but she gives no quarter. She is always, unconquerably, herself. Never more so than when, sent off by her mother on behalf of the family budget, she arrives in still bourgeois Peckham to become a maid.

‘This, dears,’ said the youngest sister, ‘ is the little girl who has come after the place. She looks willing, and my idea is that we might take her for a month, at any rate. Her mother is a good worker.’

‘I expect Letty is right,’ said one of the elder sisters. ‘ What is your name, my girl ?’

‘Mord Em’ly.’

Name interpreted by the youngest sister.

‘Oh, you must really learn to pronounce distinctly. You should say Maud, and then wait for a moment, and then say Em-ily.’

‘All very well,’ said Mord Em’ly, ‘ if you’ve got plenty of time.’

‘Are you a hard worker, my girl ?’

‘Fairish, miss. I ain’t afraid of it, anyway.’

‘I think we shall decide to call you Laura if you stop with us.’

‘Whaffor ?’ demanded Mord Em’ly.

‘We always call our maids Laura,’ explained the eldest of the ladies complacently. ‘It’s a tradition in the family. And my youngest sister there, Miss Letitia, will look after you for the most part. My other sisters are engaged in—er— literature; I myself, if I may say so without too much confidence, am responsible for’—here the eldest sister looked in a self-deprecatory manner at the toe of her slippers— ‘art.’

‘My sister Fairlie,’ went on the eldest lady in a lecturing style, and pointing with her forefinger, ‘ writes under the pen name of ‘George Willoughby,’ and has gained several prizes, some of them amounting to as much as one guinea. My sister Katherine pursues a different branch. Her speciality to use a foreign expression, is the subject of epitaphs—queer epitaphs, ancient epitaphs, pathetic epitaphs, singular epitaphs, amusing—’

‘Talking about epitaphs,’ interrupted Mord Em’ly, ‘ how much do I get a year for playing in this piece ?’

Unsurprisingly Number 18 Lucella Road, SE does not hold her long. The bright lights of Walworth are far more alluring.

What matters is freedom and after a series of misadventures which include reform school (and she is to an extent ‘reformed’, or certainly enough to gain her discharge), the book ends as she sails off with the one boy who, still on her own terms, she has permitted to woo her. They are destined for a new life in that emblematic land of liberty: Australia (not yet self-advertised as ‘the lucky country’ but to Mord, ‘a good deal like South London, only better.’) Walworth may have teemed with Mords but real-life London would have trampled their joyous self-sufficiency. Like his cockneys, Mord’s merry life is Pett Ridge’s fantasy: its only hope was to journey to what was still a fantasy land.

Given how many of his contemporaries remain recognisable, important names, it is odd that Pett Ridge fell so quickly between history’s cracks. As his fellow-author Michael Moorcock described him, in London Peculiar (2012), he was ‘the most famous literary Londoner of his day. He walked everywhere. He knew the city from suburbs to centre. He knew everyone, an energetic social reformer, he was a good friend of HG Wells, JM Barrie, WS Gilbert, Jerome K Jerome, E Nesbit and many contributors to the Pall Mall Gazette, The Idler, Westminster Gazette, journals of what we’d today call the moderate left. All testified to his experience and talent. “There is nobody else in London,’ said JM Barrie, ‘with his unique literary ear”.’

Yet he has effectively vanished. Why? It cannot have simply been his desire to create laughter rather than guilty tears. P.G. Wodehouse, whose career was beginning as Pett Ridge’s drew to its close, has survived magnificently. Perhaps those middle-class Londoners who wished to read about their contemporaries to the East were not ready for a cheery portrait. The gutsy urban ‘sparrer’ was less to their taste than the crushed sufferer, susceptible to the interference of do-gooding ‘missionaries’ and duly grateful for their condescension. The East End woman was either reeling from her violent husband’s fists or belt, neglecting her children or drowning herself in the bottle – often all three at once; worse still she might be walking the streets. She was object, not subject and whether literally or metaphorically, she did not answer back.

If this was as much a fantasy as was Pett Ridge’s portrait of Mord Em’ly, it was the one that contemporary readers preferred. Later critics were no more enthusiastic. Even if they had side-stepped the mawkish stereotypes, the Cockney novelists were now dismissed: their humour was disdained as sentimental and their jokes as no more than facetious; the whole package was simply an attempt to make West Enders feel less guilty. Their best-known names – Henry Nevinson, Edwin Pugh, Arthur Morrison and others – simply disappeared from the literary canon. There was no reason, and so it proved, for William Pett Ridge to prove an exception to the rule.

Jonathon Green is the world’s leading lexicographer of Anglophone slang. His work can be found online at www.greensdictofslang.com. He is currently working on a study of the relationship of women and slang, with the working title of Sounds and Furies.

All rights to the text remain with the author.