Anne Fernald

This article was first posted at The Awl and is reposted here with the author’s kind permission.

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, published in 1925, is set on a single day in London in June 1923. It tells the parallel stories of Clarissa Dalloway, who is throwing a party, and Septimus Warren Smith, a shell-shocked World War One veteran. A perfect high modernist work, here are some of the reasons why the book still matters.

Woolf makes us care about a fancy middle-aged lady throwing a party.

From the opening line of the book — ‘Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.’ — we know we are with a married woman who is rich enough to have people around her to do errands for her. If most of us need flowers, there is no one to tell; Mrs. Dalloway has maids. Some people confuse Virginia Woolf with Mrs. Dalloway, but it’s more accurate to say that Mrs. Dalloway represents the world that Woolf’s mother (who died when Woolf was just thirteen) imagined for her, a conservative, social world that Woolf left behind for art, feminism, and Bloomsbury. In asking us to empathize with Clarissa even while she shows us that Clarissa is a shallow, silly woman who has little to show for her fifty-two years, Woolf returns to all she rejected and finds the possibility that even the people she most rebelled against have souls, have regrets, and have ways of living with courage in spite of it all.

The characters have great names that have interesting histories.

Clarissa shares her name with both the heroine of Samuel Richardson’s 1747-8 novel and the character who, in Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (1711-14) provides the scissors to cut off (thus, “rape”) the lock of Belinda’s hair. In early 1925, just after finishing Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf wrote an essay on The Rape of the Lock, in which she compared Pope to Chekhov. Thus, Clarissa Dalloway, whom we see with her sewing scissors and who seems virginal in spite of marriage and motherhood, is associated with both the accessory to a satiric “rape” and the most famous rape victim in the history of the novel. Septimus’s name seems weirder to us now than it once did. In large Victorian families, the parents of seventh-born children occasionally threw up their hands and began numbering their offspring. Woolf’s brother’s nanny in the early 1920’s was a seventh-born child, Daisy Selwood, nicknamed Septima. And, in the large blended family of Leslie Stephen and Julia Duckworth Stephen, Woolf herself was the seventh-born child.

It’s a great example of a novel set on a single day.

Woolf was famously unable to appreciate Joyce’s Ulysses, calling it an “underbred” book. However, three years later, in Mrs. Dalloway she tried the same experiment. The verbal pyrotechnics of Woolf’s novel are different (see below), but the tolling of Big Ben’s bells marks the hours throughout the novel and, like Joyce, Woolf uses modernist techniques to offer us glimpses of the thoughts and memories of characters who only exist for a single day. The Hours was an early title for Mrs. Dalloway and the finished novel does not have chapters, but section breaks. Those section breaks have been plagued with errors since the first printing, where several section breaks fell at the bottom of a page and thus became invisible. However, if you follow Woolf’s instructions, the novel has exactly twelve sections, hardly a random number for a daylong novel. The longest section begins at noon.

Woolf deploys allusions to Shakespeare like a master.

There are a lot of allusions in Woolf, and a lot of them are easy to miss. When you get them, however, they deepen the story. One of the main ways that we learn to see Clarissa as a kind and sympathetic person is through a literary coincidence: although she never meets Septimus, both characters take comfort in the same song from Shakespeare’s somewhat obscure late romance, Cymbeline: ‘Fear no more the heat of the sun / Nor the furious winter’s rages.’ This dirge, sung over the body of an apparently dead boy (but really a living girl) connects the living woman to the soon-dead man. Other allusions to Shakespeare are similarly calculated to exercise your inner English major. Woolf plays with gender roles again when Clarissa remembers her love for Sally Seton when they were younger by quoting Othello, upon first reuniting with Desdemona: ‘if it were now to die ‘twere now to be most happy.’ We can guess that Septimus’ volunteering for war will be ill fated when he associates his love for his teacher, Miss Isabel Pole with Antony and Cleopatra, and not, say Twelfth Night. And finally, Lady Bruton, who should have been a general, gets to quote Richard II while Woolf simultaneously takes pleasure in and makes fun of her patriotism: ‘this isle of men, this dear, dear land, was in her blood (without reading Shakespeare).’

It continues to inspire other works of art.

Toni Morrison wrote her M.A. thesis on Woolf and Faulkner and you can see a direct link between Septimus and Shadrack, the WWI veteran and founder of National Suicide day in Sula. Gregoire Bouillier’s memoir The Mystery Guest (appropriately tongue-in-cheek trailer here), set around one of performance artist Sophie Calle’s birthday parties, has the Bouillier and Calle’s mutual admiration for Mrs. Dalloway as a central conceit. Michael Cunningham’s The Hours and the movie of the same name are really lovely tributes to the book. The Laura Brown section, about a discontented housewife reading Mrs. Dalloway, Doris Lessing-style, alone in a hotel room, is particularly smart and made so much better when linked to the novel. And, although Ian McEwan would rather have you think of him with Bellow and Mailer, his Saturday, about a wealthy surgeon whose spends the day getting ready for a party under the shadow of 9/11, is, of course, a retelling of Mrs. Dalloway.

It’s full of London history.

Richard Dalloway tsk-tsks the terrible traffic at Piccadilly Circus, and in doing so, he records an ongoing London problem of the time. In fact, buses, hand- and horse-drawn carts, carriages, automobiles and pedestrians all competed to cross streets at a time when traffic signals still had to be changed manually by a traffic officer. Traffic in Piccadilly especially was the subject of many newspaper articles and resulted in multiple government committees, studies and reports during the early 1920’s—committees of just the kind that Richard, as a Member of Parliament might sit on. This 1927 film clip offers a sense of the traffic.

Early in the novel, the driver of the mysterious car on Bond Street waves an ivory disk and escapes another traffic jam. Such passes are now largely forgotten, but were once a common perk for railway directors and other people of privilege. You can see one such ivory disk, a coach pass, here.

When Clarissa shops at Hatchard’s, she is shopping at Lord Byron’s bookshop, a shop that has been at the same London address, catering to aristocratic poets and fancy ladies buying books for their friends in hospital since 1797. But when she thinks of having been to parties at Devonshire House, she is marking the passage of time: Devonshire House was demolished in 1924, after the novel’s 1923 setting but before its 1925 publication date. Devonshire House is preserved in Clarissa’s memory, and her memory of it is another clue to her own coming obsolescence.

Even the random details are not random.

Joseph Breitkopf, who once taught Clarissa German but really prefers to sing lieder, shares his surname with the pre-eminent German music publisher. When Hugh consults a clock outside the fictional department store, Rigby & Lowndes, not only are R-I-G-B-Y (5) and L-O-W-N-D-E-S (7) precisely twelve characters, (one for each hour on the clock face), but they were the surnames of English suffragettes. In 1913, Edith Rigby threw a black pudding at a Labour MP in Manchester and set a bomb (which did not explode) under the Liverpool Cotton Exchange. Mary Lowndes was a stained glass artist and a regular contributor to the feminist magazine The Englishwoman.

We still need to remember to take care of veterans and we still don’t do enough.

When Clarissa hears of Septimus’ suicide, she retreats from her party. In a quiet room, she thinks about him with great sympathy and, in his death, finds courage to rejoin her life. Many people find that moment, when she stands alone, looking across the way at the old woman opposite, one of the most beautiful moments in the novel. The novel depends on our conviction that, more than any of the other characters, Clarissa understands Septimus’ decision to end his life. And Woolf shows us to link that decision, arising out of despair, with the lack of sympathy Septimus faces, especially from his doctors. In the 1920’s, many people still looked on war trauma as cowardice and there was some support for treating suffering veterans as deserters. I don’t think it’s entirely satiric when the men harrumph, on the news of Septimus’ death, that ‘there must be some provision in the Bill.’ In the end, Woolf values Clarissa’s sympathy more, but I think Woolf shows us the decency in Richard’s actions, too. Septimus’ death is an offering and a statement, an act of desperation in the face of continued appalling medical care—in this moment, the prospect of being sent away from London and his wife.

Woolf, who suffered from depression off and on throughout her life, knew too well what bad doctors could be. In the 1920’s, the care Woolf endured—isolation, forced inactivity, over-feeding—was identical to what most shell-shock victims would have endured. Only a very, very few physicians, such as W. H. R. Rivers, had begun a talking cure as treatment for war trauma. For Woolf, suicide was a decision and could be a rational one. The only page that Woolf substantially changed in revising the page proofs is the page on which Septimus commits suicide. To that page, she added his thinking about how to do it: taking Mrs. Filmer’s bread knife into consideration—’mustn’t spoil that,’ he thinks; wondering about gas and razors; embarrassed to have to throw himself out the heavy Bloomsbury lodging house window.

Anne Fernald is a professor at Fordham University in New York City. She is the author of Virginia Woolf: Feminism and the Reader (Palgrave, 2006) and the editor of a textual edition of Mrs. Dalloway for Cambridge University Press (2014). Her personal website is at annefernald.com

Clarissa Dalloway’s London

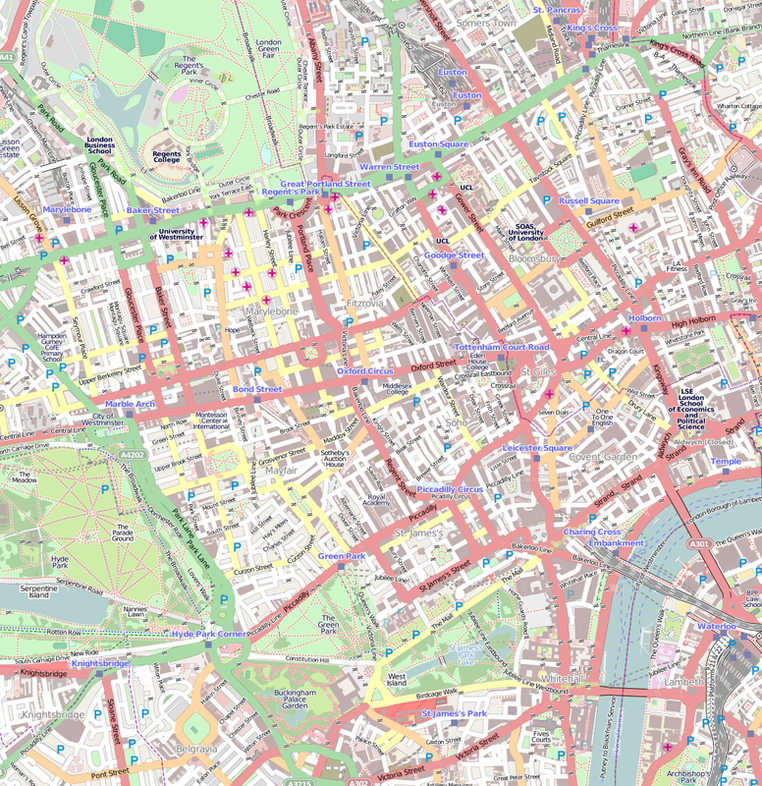

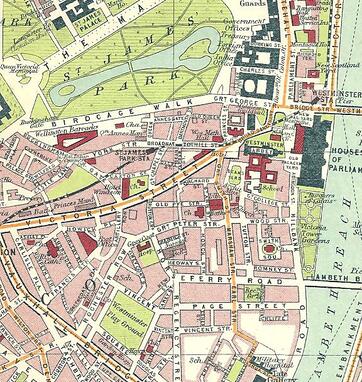

Clarissa Dalloway’s Westminster home is never precisely located – it seems to be in or around Great College Street, within a few minutes walk of Parliament and the major ministries.

We first come across her in Dean’s Yard, behind Westminster Abbey, and as she traverses central London, we see her crossing Victoria Street and entering St James’s Park

A little later, Mrs Dalloway is walking along Piccadilly towards Bond Street – while on Piccadilly, she looks into Hatchard’s, then as now a leading bookshop.

Intersecting with Clarissa’s walk is the journey of Septimus Warren Smith and his Italian wife, Rezia – they are in Bond Street, then in Regent’s Park to the north, and later in Portland Place and on to Harley Street to see a leading doctor. Another medical man, Dr Holmes, comes to the Warren Smiths’ home in Bloomsbury to take Septimus away to an institution – prompting the shell-shocked young war veteran to jump out of a window to his death. Other characters are plotted precisely as they walk … across Green Park – along Fleet Street – always within a fairly circumscribed area of central London, never more than a mile or so from Westminster Bridge.

These paragraphs have been informed by the section ‘A Walking Tour with Mrs Dalloway’ in David Daiches and John Flower, Literary Landscapes of the British Isles, first published in 1979. And here’s a brief extract:

‘If one does not follow the topography of the novel one loses a great deal. Virginia Woolf’s sense of London helps her to define the characters and her sense of the characters helps her to define London, to a greater degree than in any other of her novels. … the London that really haunted her imagination was her own London, where she was born and grew up and spent so much of her life, the London which, as her diary shows, she rediscovered with excitement every time she came back to it after an absence.’

Andrew Whitehead

References and Further Reading

‘As one of the great London novels, Mrs Dalloway not only takes us on a delicious tour of some of the capital’s major attractions, it also conveys better than any major work of fiction that I can think of the enhanced sense of “being alive” stimulated by the energy, variety and complexity of city life. …’