Colin Stanley

He came out of the Underground at Hyde Park Corner with his head lowered, ignoring the people who pressed around him and leaving it to them to steer out of his way.

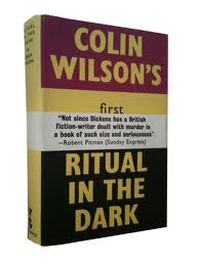

Thus begins Colin Wilson’s debut novel, first published in 1960, described by the critic Nicolas Tredell in 2011 as ‘an unsung achievement of post-war British fiction.’ It is a novel not only set in London but, in the course of its writing, inextricably linked with post-war London literary history.

‘He’ is Gerard Sorme, the hero of a trilogy of novels that would unfold in the ensuing decade, on his way to Richard Buckle’s Diaghilev exhibition — actually held at Forbes House, Hyde Park Corner in 1954 — where he meets Austin Nunne for the first time. After viewing the exhibition they move on to a club in Dover Street, enjoy a meal at a restaurant in Dean Street, Soho, ending-up at the renowned ‘French pub’.

‘He’ is Gerard Sorme, the hero of a trilogy of novels that would unfold in the ensuing decade, on his way to Richard Buckle’s Diaghilev exhibition — actually held at Forbes House, Hyde Park Corner in 1954 — where he meets Austin Nunne for the first time. After viewing the exhibition they move on to a club in Dover Street, enjoy a meal at a restaurant in Dean Street, Soho, ending-up at the renowned ‘French pub’.

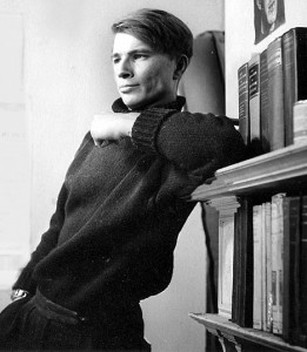

Colin Wilson was born on June 26, 1931 in Leicester — the first child of Arthur and Annetta Wilson. At the age of eleven he attended Gateway Secondary Technical School, where his interest in science began to blossom. When just fourteen he compiled a multi-volume work of essays covering all aspects of science entitled A Manual of General Science. By the time he left school at sixteen, however, his interests were already switching to literature. His discovery of George Bernard Shaw, particularly Man and Superman, was an important landmark. He started to write stories, plays, and essays in earnest—a long ‘sequel’ to Man and Superman made him consider himself to be ‘Shaw’s natural successor’. After two unfulfilling jobs — one as a laboratory assistant at his old school — he drifted into the Civil Service, but found little to occupy his time.

In the Autumn of 1949, he was drafted into the Royal Air Force, but soon found himself clashing with authority. Frustrated and bored, he finally invented a story that he was homosexual, in order to be discharged. Incredibly he was discharged and, upon leaving, took up a succession of menial jobs, spent some time wandering around Europe, and finally returned to Leicester in 1951. He arrived in London, on June 7 that same year, aged just 19, spent the night at the youth hostel in Great Ormond Street and then found himself a room at the end of Rochester Road in Camden Town. The next morning, at the Labour Exchange, he was given a job helping to replace the beams in the ceiling of St. Etheldreda’s church in Holborn, damaged during the blitz.

Ritual had begun life in 1949, when Wilson was just 17, as an unpublished short story: ‘Symphonic Variations’. After completion, he decided to turn it into a full-length novel. It was this that his friend, and fellow would-be novelist, Laura Del Rivo — whose own London novel, set in Notting Hill, The Furnished Room (republished by Five Leaves in 2011), heavily influence by Ritual, was published in 1961 and filmed by Michael Winner in 1963 as West 11 — recalls seeing in manuscript in the Northumberland Avenue café where they first met in 1952:

Colin was 21 when he appeared in the Café. He was lanky, bespectacled, practical in maintenance skills, everyouth except that he was a genius. He rode a bicycle for which he wore trouser clips. Sometimes the ladder he used for speaking in Hyde Park was fastened to the crossbar. Although like Sorme he was the hero of his own intellectual bildungsroman, he was already a lecturer. He carried a leather satchel which contained spare food and a manuscript: literally handwritten: of his work in progress, the ‘Sorme-book’, Ritual In the Dark.

This was almost certainly the copy of the manuscript that was with him in his sleeping-bag when he famously slept rough, to save money, on Hampstead Heath and which he took to the British Museum reading room each morning where he was spotted and encouraged by its Deputy Superintendent, Angus Wilson (no relation), himself an emerging novelist. (Sorme also visits the reading room where he orders-up some books then has tea at a café on the Charing Cross Road before returning, some hours later, to read them. The B.M. has featured in no fewer than ten of Wilson’s novels, including Ritual).

But this was far from being the final version. ‘Symphonic Variations’ had been transformed into a novel with the somewhat unpromising title, Things Do Not Happen, which, upon Wilson’s discovery of The Egyptian Book of the Dead (which provided a structure for this version), became Ritual of the Dead. His aim was to produce a Dostoyevskian novel, using the techniques made available by James Joyce and Henry James.

But this was far from being the final version. ‘Symphonic Variations’ had been transformed into a novel with the somewhat unpromising title, Things Do Not Happen, which, upon Wilson’s discovery of The Egyptian Book of the Dead (which provided a structure for this version), became Ritual of the Dead. His aim was to produce a Dostoyevskian novel, using the techniques made available by James Joyce and Henry James.

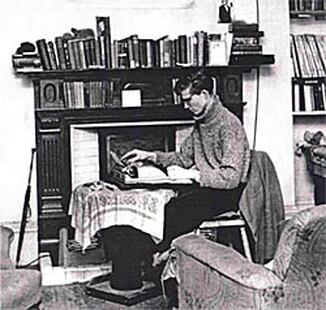

In January 1955, Angus offered Colin the use of his cottage in the countryside, near Bury St Edmunds, so that he could finish the book undisturbed. In his autobiography, Dreaming to Some Purpose, Colin Wilson writes:

I worked hard, and managed to finish Ritual in two weeks, but I was dissatisfied with it. This was not the novel I had been trying to write for so many years. It lacked real narrative flow. … I had written and rewritten it all; some pages had been typed a dozen times. The final manuscript was barely seventy thousand words long, and yet I had probably written half a million words over five years. All this meant that I could not approach the task with a fresh outlook; I had lost my critical sense completely about some of the older passages. It was like trying to rebuild a house that you have pulled down twenty times, using a mixture of old and new bricks.

It was this version of the manuscript that the clientele often saw stuffed under the counter of the coffee bar in which he worked, on London’s Haymarket, during 1955. By this time Colin Wilson had moved lodgings to Notting Hill, a house on the corner of Chepstow Villas, ‘completely dilapidated’ with peeling wallpaper and broken windows (incredible when you consider those properties today) where he rented a room for a pound a week! His girlfriend Joy Stewart joined him there a little later.

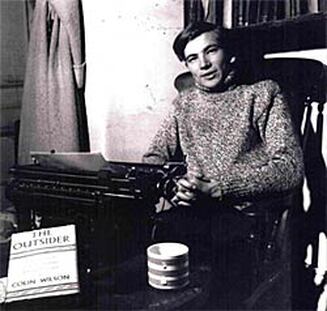

A sort of impasse had been reached with Ritual and Wilson turned his attention to non-fiction, producing three books in his ‘Outsider Cycle’, including his first and most famous, The Outsider, before returning to the novel. The Outsider was published on Monday, May 28, 1956, to tremendous critical acclaim, and, at 24 years of age, he became a celebrity overnight, one of Britain’s ‘Angry Young Men’: a movement created by the media to fill the literary vacuum that then existed, and which they then destroyed soon afterwards.

It was in the following year that, at Chepstow Villas, Wilson’s future father-in-law infamously threatened him with a horse-whip after reading his journal — which contained notes about the Jack the Ripper murders intended for inclusion in Ritual — and fearing for his daughter’s life! This resulted in said journal being splashed all over the tabloid press causing Colin and Joy to abandon London temporarily and hasten their decision to eventually move to Cornwall permanently in 1958 (where they still live). By this time the fierce backlash against the ‘Angry Young Men’ had taken hold and, as a result, Wilson’s second book Religion and the Rebel had taken a severe pounding by the critics. This and the ‘horse-whipping scandal’ encouraged Victor Gollancz, his publisher, to advise his protégé to leave the capital at least until all the fuss had died down.

Further revision of Ritual had been put on the back-burner until The Outsider sequels — Religion and the Rebel (1957) and The Age of Defeat (1959) — were completed. The break was obviously beneficial and enabled him to look at his manuscript more objectively. He decided that he ‘had to treat it as a story, a narrative, and forget James Joyce and The Egyptian Book of the Dead. And since the novel was about a sadistic killer based on Jack the Ripper, it obviously had to be written as a kind of detective story’.

The three male protagonists — Gerard Sorme, Oliver Glasp and Austin Nunne — epitomised the three types of outsider enunciated in his first book: intellectual, emotional and physical; they were based on T. E. Lawrence, Vincent Van Gogh and Vaslav Nijinsky. ‘Nunne, Glasp and Sorme are the body, the heart and the intellect of the same man….Their separation is a kind of legend of a fall,’ he wrote in an early notebook for Ritual. Dostoyevskian indeed … The Brothers Karamazov springs to mind here. James Joyce was also not entirely abandoned: the lack of speech marks, throughout the finished novel, nods in his direction, and Wilson was to write in 1998: ‘I have never ceased to be grateful to Joyce; Ulysses taught me more about writing than I learned from any other writer.’

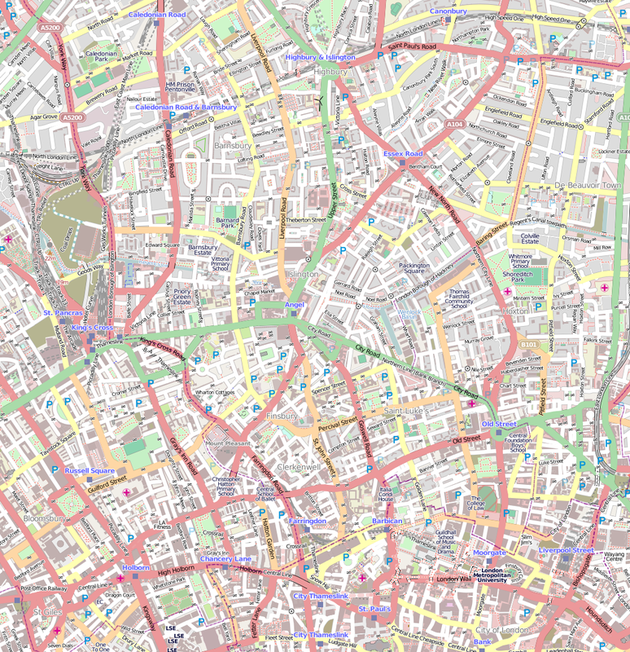

But it was his move to the capital that had proved most fortuitous for it gave the novel authenticity and a sense of place. Indeed Sorme’s perambulations can be followed closely on an A-Z map: he too has a bedsit in Camden Town; Nunne has a flat in Canning Place off Palace Gate and another residence opposite Great Portland Street station; Gertrude Quincey, Nunne’s aunt, has a house on the Vale of Health near Hampstead Heath; Father Carruthers, the sickly priest in whom Sorme confides, lives at a hostel on Rosebery Avenue; the artist Oliver Glasp lives in Durward Street, scene of the first Jack the Ripper murder in 1888 (when it was known as Buck’s Row). Sorme spends a great deal of the novel cycling, taking a tube, bus or taxi between these locations and, as a number of murders take place at or near the original Ripper murder sites in Whitechapel, the East End too. Mirroring the original murders, there is a ‘double event’ during one night at Mitre Square and Berner Street. Subsequently Wilson became an acknowledged expert on the murders: a ‘Ripperologist’, a term he actually coined. Soon after publication of Ritual the London Evening Standard commissioned him to write a series of five articles: ‘My Search for Jack the Ripper’ which were published during August 1960. A full-length book with Robin Odell Jack the Ripper: Summing Up and Verdict appeared in 1987 in time for the 100th anniversary of the murders.

Ritual itself is set in 1956 and you get a sense of a city and its people still struggling to rebuild itself, and their lives, after the wartime blitz. Following a meal with Caroline, Gertrude Quincey’s niece, in a basement restaurant on the King’s Road, the two attend an impromptu party around a bonfire on a bomb site, which the fire brigade are obliged to extinguish. They decamp to a houseboat moored off Cheyne Walk.

Sorme’s own accommodation is one step above squalid. There is an all-pervading drabness, highlighted by the opulence of Nunne’s lifestyle and the middle-class comfort of Gertrude Quincey’s. Sorme observes that ‘London in November has no daylight. Only dusk. And London in July has too much daylight. Unreal or too real.’ (57) However the vibrancy of his surroundings has a profound effect upon him. He awakes one night in a state of great excitement thinking:

I am lying here in the middle of London, with a population of three million people asleep around me, and a past that extends back to the time when the Romans built the city on a fever swamp … I can’t explain what I felt. It was a sense of participation in everything. I wanted to live a million times more than anybody has ever lived. (66)

Later in the novel, approaching Westminster Bridge, like Wordsworth before him, he even has his own (albeit very 1950s) epiphany: ‘…the river looked like a sheet of rayon in the sunlight; it was difficult to believe in murder in the unexpected warmth.’ (374)

It was his friend, and fellow ‘Angry Young Man’, Bill Hopkins (whose own novel The Divine and the Decay had just been published in 1957) who suggested to Wilson that he start Ritual at the aforementioned Diaghilev exhibition. The result is one of the most memorable opening chapters in post-war English literature. After refusing an earlier version, publisher Victor Gollancz accepted this and it was eventually published in February 1960, over eleven years after its conception.

Edith Sitwell in The Sunday Times declared it ‘…an unforgettable, really great evocation….An important book’. The Sunday Express reviewer wrote: ‘Not since Dickens has a British fiction writer dealt with murder in a book of such size and seriousness’ and in the US the Chicago Sun-Times exclaimed ‘Magnificent! Murder mystery raised to high art!’ However, J. Rayner Heppenstall of the Times Literary Supplement was not so impressed, predicting that Wilson had written his first and probably last novel.

When Ritual was published in French by Gallimard in 1962, reviews there were outstanding: the book was hailed as one of the most important novels by a young writer since the war; one critic spoke of Wilson as ‘the natural successor of Lawrence, Huxley and Orwell’.

Soon after publication, Wilson worked on the screen-play with a young writer called Steven Geller (who ran a film company, Pequod Productions) and it seemed that shooting would go ahead. In a letter to the actress Renée Asherson dated December 6, 1967, Wilson wrote, ‘It looks as if the film will be made in London in either March or April [1968].’ Asherson was to play Gertrude, and Jane Asher, Caroline. Michael O’Sullivan was lined-up for the part of Austin Nunne. However, the promised financial backing was withdrawn and the film never realised.

‘In its final version,’ wrote Sidney Campion, ‘Ritual In the Dark has a technical mastery that is astonishing in a first novel. All the “experimental” aspects have been ironed out; the novel reads so easily and smoothly that the reader is unaware that it is a novel of ideas.’ But a novel of ideas it most definitely is and it is this extra dimension that elevates it above and beyond novels written purely for entertainment.

Wilson is, of course, best known for his non-fiction: his philosophical study The Outsider — which has been translated into over 30 languages and never been out-of-print since 1956 — was followed by six more books in the ‘Outsider Cycle’ culminating in An Introduction to the New Existentialism in 1966. This established him as an existential philosopher. In the late 1960s, he turned his attention to the occult. His now classic study The Occult appeared in 1971 and was followed by two more equally bulky books Mysteries (1978) and Beyond the Occult (1988). These solid offerings spawned many other lesser works on the subject. Staggeringly prolific, he has produced over 150 books but whether writing about psychology, true crime, unexplained phenomena, pre-history, the occult, music or literature, a positive philosophy of optimism pervades his work, both popular and more academic:

The problem that lies at the heart of my work is the problem of the curiously unsatisfactory nature of human consciousness. Human beings know what they don’t want far more clearly than they know what they do want. The paradoxical result is that man is magnificent in crisis; yet as soon as life begins to flow smoothly, he becomes oddly bored. There is an absurdity in this situation — rather like buying a car that will do ninety miles an hour in reverse, and only ten miles an hour going forward.

Wilson believes he has found the answer to this crucial problem through his association with the celebrated American psychologist Abraham Maslow and his concept of ‘peak experiences’ (those sudden moments of joy and affirmation that all psychologically healthy people experience with a fair degree of frequency). He is convinced that if we can make the effort and learn to encourage these moments of affirmation, not only will we live more vital and appreciative lives but this will trigger a change in consciousness that will change everything.

Novels are an essential element of his work, bringing his philosophical ideas to life, as he explained in 1975:

Ritual in the Dark had been closely connected to The Outsider, and I now found it natural to write a novel and a philosophical book at about the same time. Ideas tended to shape themselves into characters and events. Origins of the Sexual Impulse was followed by the novel, Man Without a Shadow.

In all, he has published twenty-two, many of the earlier ones set in London. This includes Adrift In Soho (1961) — republished by Five Leaves in 2011 — soon to be filmed by the Uruguayan film director Pablo Behrens. This chronicles the experiences of a young man, fresh from the provinces, thrust into the heady environment of 1950s Soho. Man Without a Shadow (1963) — republished by Valancourt Books in 2013 — follows on from Ritual and reveals what Gerard Sorme did next. In a later novel, The Glass Cage, published in 1966, Damon Reade, a William Blake scholar, is approached by the police in the hope that he can help them catch the Thames Murderer who leaves quotes from Blake beside each victim.

Ignored in assessments of post-war English fiction, and a forgotten classic of London fiction, Ritual In the Dark is, however, the favourite of many fans and scholars and also, it appears, of Colin Wilson himself: ‘…it is my most solidly constructed and satisfactory novel,’ he wrote in 1993, ‘It is, at all events, my own favourite.’ Also republished in 2013, it is hoped that this will encourage a reassessment by a new generation of readers and critics. ‘Wilson’s first novel,’ wrote Nicolas Tredell, ‘is a powerful metaphysical thriller. It combines a number of modes: the realistic novel of the 1950s; the Bildungsroman; the murder story. It also contains elements of fantasy and myth. All these fuse into a rich totality….It is fascinating to think about; but it is no less fascinating to read and re-read.’

Colin Wilson died on December 5th, 2013 and his body was interred in the churchyard of St Goran, near his home in Cornwall.

Colin Stanley is the Managing Editor of Paupers’ Press (www.pauperspress.com), the author of two experimental novels, a slim volume of nonsense verse and several books and booklets about Colin Wilson and his work. He is the editor of Colin Wilson Studies, a series of books and extended essays, written by Wilson scholars worldwide and Around the Outsider, a volume of essays to celebrate Colin Wilson’s 80th birthday in 2011. His collection of Wilson’s work now forms The Colin Wilson Collection at the University of Nottingham, an archive opened in 2011. He now works as a freelance writer, speaker and publisher and lives in Nottingham with his wife Gail. Page numbers refer to the edition of Ritual in the Dark published by Valancourt Books (Kansas City, 2013).

References and Further Reading

Sidney Campion, The Sound Barrier: a study of the ideas of Colin Wilson, Nottingham: Paupers’ Press, 2011.

Colin Stanley (ed), Around the Outsider: essays presented to Colin Wilson on the occasion of his 80th birthday, Winchester: O-Books, 2011.

Colin Stanley, Colin Wilson’s ‘Occult Trilogy’: a guide for students, Alresford, Hants: Axis Mundi Books, 2013.

– Colin Wilson’s ‘Outsider Cycle’: a guide for students, Nottingham: Paupers’ Press, 2009.

– The Colin Wilson Bibliography, 1956-2010, Nottingham: Paupers’ Press, 2011.

Nicolas Tredell, Novels to Some Purpose: the fiction of Colin Wilson, Nottingham: Paupers’ Press, 2015.

Colin Wilson, Adrift in Soho,Nottingham: Five Leaves, 2012 (first published 1961).

– Dreaming to Some Purpose, London: Century, 2004.

– The Books in My Life, Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads Publishing Company, Inc, 1998

– The Craft of the Novel, Bath: Ashgrove Press, 1986.

– The Glass Cage, London: Arthur Barker, 1966.

– Man Without a Shadow, Kansas City: Valancourt Books, 2013 (first published 1963).

The Colin Wilson Collection at the University of Nottingham –

http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/ManuscriptsandSpecialCollections/News/2009/ColinWilsonCollection.aspx

The Jack the Ripper Casebook –

http://www.casebook.org/intro.html

All rights to the text remain with the author.