Stewart Home

This article was first published on Stewart Home’s website, and is posted here in slightly revised form with his permission.

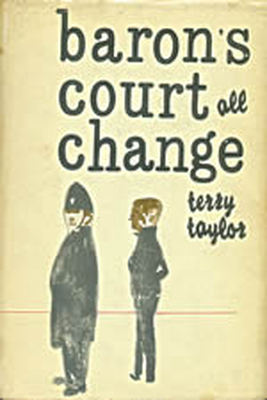

Stewart Home has written the introduction to a new edition of Baron’s Court, All Change, published by Five Leaves in 2011.

The Katz Kradle’s considered the best Jazz Club in this country, but I hate it. Although I go there week after week, I think it stinks. The music’s great, and they’ve spent hundreds of pounds on the decorations (I’m not kidding either, Jazz is big business), but it’s the members that spoil it. … We get our kicks, though. If it’s not a friendly discussion it’s trying to lay a chick, and if it’s not that it’s probably having a good old smoke up in the carzy. And there’s always something happening at the death. One of the cats that has his own pad will give an impromptu party where we all get stoned and have a ball, and if we’re lucky we managed to lumber a dealer back with us and get him really block-up so that he starts to get generous and brings out a dirty great ounce as his contribution to the gaiety

Yeah, you read that right, so now dig this: Baron’s Court, All Change is the Holy Grail for all collectors of beatnik, mod and hippie ephemera. This is it dude, straight from the fridge, a novel so groovy and ahead of its time that it joined the Legion of the Reforgotten faster than the publisher was able to dispatch it to the shops. Set in the very late-fifties (as far as author Terry Taylor can recall, or possibly even 1960), it documents one summer in the life of the unnamed sixteen year-old narrator who leaves his suburban home and boring job as a shop assistant for a pad in central London, courtesy of the money he makes from a break into dealing charge (grass to you and me, Indian Hemp to the squares back in the day).

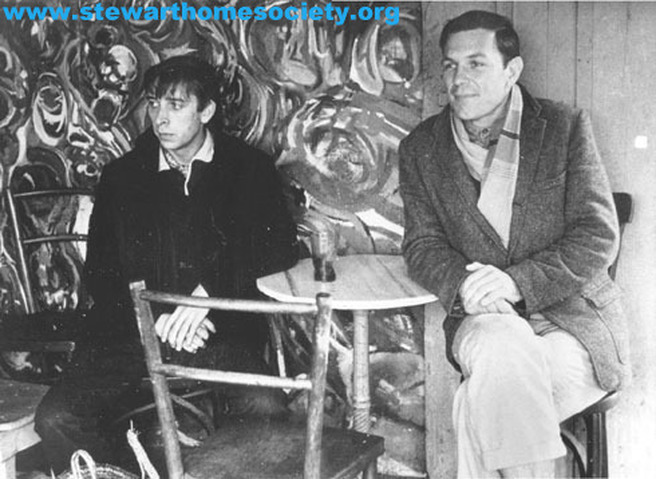

Taylor was born in 1933 and inspired the novels Absolute Beginners and Mr Love and Justice by Colin MacInnes; and aside from being an assistant to noted photographer Ida Kar (and also her lover despite a huge age difference between them), Terry was also a hustler; so he knew a thing or three about drug dealing. What Taylor lays out in this novel is the little known London beatnik scene that fed directly into both the mod movement and the British end of the hippie scene. There is a sub-plot about the narrator’s sister Liz getting knocked up by her boyfriend and having an illegal abortion, but that need not detain us. Of greater interest to me is the narrator’s involvement with spiritualism, which leads to a fling with a much older woman called Bunty Ryan:

Taylor was born in 1933 and inspired the novels Absolute Beginners and Mr Love and Justice by Colin MacInnes; and aside from being an assistant to noted photographer Ida Kar (and also her lover despite a huge age difference between them), Terry was also a hustler; so he knew a thing or three about drug dealing. What Taylor lays out in this novel is the little known London beatnik scene that fed directly into both the mod movement and the British end of the hippie scene. There is a sub-plot about the narrator’s sister Liz getting knocked up by her boyfriend and having an illegal abortion, but that need not detain us. Of greater interest to me is the narrator’s involvement with spiritualism, which leads to a fling with a much older woman called Bunty Ryan:

As we entered the flat the smell changed from floor polish to perfume. It was dimly lit with concealed lighting… I could tell she wanted to impress me. She did as well. My sixteen year old mind really lapped everything up. Two different coloured walls; pink and lavender, well, that was really something. … She even had sounds in the gaff, too. A fair sprinkling of all the names, but Diz and Kenny Graham with their Afro stuff seemed to be favourites. It wigged her like mad to know that I was already on the Jazz scene. It’s the only music that I’ve ever been enthusiastic about. ….For those amongst you who do not care, or haven’t bothered to care about Jazz, all I can say is that you’re missing a great deal out of life. I suppose the highbrow stuff is satisfying to a degree, but the thing is, you know what’s coming next. In Jazz, most of it’s improvised, dig? And you never know what’s up the musician’s sleeve. He takes you into his own world, and through the sounds that he blows, tells you all about himself, and when you can manage to get on his plane, there’s hardly a kick to beat it

Yes, the jazz is cool and the sex is funky. So getting down to the nitty gritty, the narrator embarks on a relationship with Bunty, but (un)fortunately this cradle-snatching stealer of his jizz fails to give the ongoing satisfaction he finds in jazz. The narrator sees through to the squareness of Bunty’s scene after meeting Miss Roach who, alongside his pal Dusty Miller, hips him to the charge kick:

Without thinking I took the spliff between my fingers and drew on it. “Not like that,” Miss Roach instructed. “Take it right in, as deep down as it can go and keep it in, that’s the main thing. When you’ve had a blow, don’t let it go, but keep breathing in air to send it right downstairs to the bargain basement.”

I did what I was told. It didn’t taste half as bad as I thought it would. In fact it was quite pleasant. It went down a lot easier than tobacco would, and before long I was inhaling hungrily at it.

“Not too much for the first time. We don’t want you cracking up,” Miss Roach said, taking it away from me.

I wasn’t concerned with her voice, because already I’d realised I was feeling different. Everything was happening so quickly. At first I wasn’t sure exactly what it was. Then it came to me that the scene was going out of focus like it does on the tele when you turn the wrong knob. But not everything. Some of the scene was still as clear, in fact, sharper, but the rest was in a fog. Certain things stood out in the room like they had a searchlight trained on them – Miss Roach – the spliffs – the clock on the mantelpiece – but most of the other things weren’t bright at all. My heart was breaking the speed limit – thumping away like mad it was, and I felt hot although the sweat on my forehead was icy cold. … So this is what it was like to be high, my mind kept telling me. It’s different to what I read in the Sunday newspapers

Within the space of about a week, the narrator becomes a seasoned pot head and after his friend Danny the Dealer is fitted up by the filth, is ready to move into the hustling scene and embark on a love affair with Miss Roach.

This is a great book and the distorted time scale reflects the druggy content, rather than simply being a goof on Taylor’s part. The story romps along and the narrator’s voice is strong enough to carry us over these chronological flaws (which include the fact that by my reckoning the narrator should have been born in 1943 or 1944, but recounts war time memories as if he was born in 1933 like Terry Taylor). When I asked Terry about this, he told me the war was a big influence on him, which was why he used his memories of it in the novel, despite the fact the narrator would have been too young to remember it.

But let’s move on from this drugged out time scale, which only serves to make this very fabulous book even more of a groove, and return to the narrator’s girlfriend Miss Roach (who is as keen on lush as she is on weed):

Miss Roach wasn’t the ideal type to take to a party where you want to relax and enjoy yourself, without having to worry about the possibility of having to carry a drunk home. She was like that cat I read about once, who kept changing his personality and now and again he’d go all ugly. Mr Hyde, I think, his name was. Well, anyway, she was like that. One minute she’d be all serious and the next she’d be as high as a kite.

Miss Roach is a gas, but the narrator clearly loves both himself and charge more than this super phat chick. The following words are reported in the book as issuing from the mouth of the narrator’s friend Dusty Miller, but that’s a minor detail, since they flew straight from the pen of Terry Taylor:

Miss Roach is a gas, but the narrator clearly loves both himself and charge more than this super phat chick. The following words are reported in the book as issuing from the mouth of the narrator’s friend Dusty Miller, but that’s a minor detail, since they flew straight from the pen of Terry Taylor:

That’s the great thing about Mother Charge, you never know which way she’s going to take you. You think after a time you know all the different paths you can travel on, but you soon find out there are others. Monday, a laughing one. Tuesday, a serious one. Wednesday, a working one. Thursday, a lazy one. Oh man, isn’t it exciting? A thousand paths to travel on and each one different.

The narrator’s drug intake in the book goes no further than pot, but he surveys other scenes; and he has a junkie friend called Popper, who provides him with the opportunity to describe the ritual of fixing up.

Better yet, when the narrator tells Popper what a great time he’s just had at a Fun Fair with his sister Liz, it leads the smackhead to suggest that he must be on some new kick: ‘”Really?” my junkie friend said, sounding interested. “What’s it now? Bennies, L.S.D., or nems?”‘. Amazingly, this appears to be the first reference to LSD in a British novel, and although its appearance here is throwaway, acid would later play an important role in Terry Taylor’s life (but that’s another story and I won’t get into it now).

After reporting this and some other banter, the narrator goes on to describe the establishment in which this particular discussion took place:

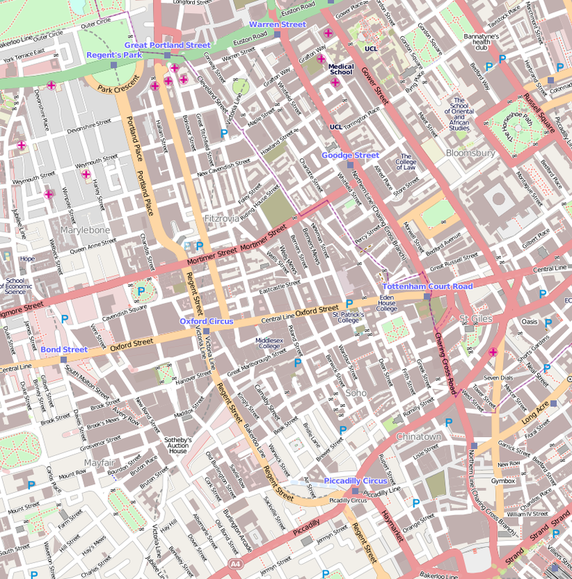

By the way, we were in a coffee bar. A dirty Soho one called The Liggery, where the strangest mixture of human beings gathered together to fix up deals that never materialise, to talk about their painting and writing and a whole gang of other things, but I’m afraid they talk more than they create. Dusty had made me promise never to pass its broken doors, as a high percentage of the inmates would sell their own crippled Granny for a night’s kip or a glass of Merrydown. There was a feeling of suicide every time you went into the place, and something unsafe and frightening to those that weren’t on the skippers kick.

The narrator’s attitude to those in this establishment is essentially that of a proto-mod (which is what he and his non-fictional double Taylor were at the time this was written). When he makes £38 profit from his first dope deal he announces: ‘I felt like a millionaire. I wanted to go to Cecil Gee and buy half their stock up or something crazy like that. This was two months’ wages….’

Cecil Gee clothes and modern jazz mark the narrator as a proto-mod (and not at all the stereotyped fish-tailed Parka wearing and Purple Heart popping creature the term mod was associated with by 1964). A few paragraphs on the narrator’s drug peddling partner Dusty Miller is described as narcissistically admiring a new shirt he’d already bought himself from ‘C Gee’s’. For all their protestations about loving music more than schmutter, Dusty and the narrator are clothes obsessed, and everyone is judged by how they look. Drag might run second to vinyl when it comes to commanding their loot, but it is a close second; and they are more than happy to spent half a note on a haircut. A rival drug peddler called Jumbo is described as: ‘…a just about young, nearly old cat sitting in the corner, who was reading a ‘Superman’ comic. He had a clean shirt on and a tie as well, but his hair was long and cut in a Boston style, which by the way went out with Dixieland Jazz. His clothes were of the post-war American style, all flash and larey, ice-blue gabardine, twenty-inch bottom slacks as well…’.

In novels, as in life, all good things eventually come to an end… and Jumbo has Dusty and the narrator beaten up, before grassing them up to the Old Bill. Fortunately the two likely lads have been hiding their stash in Miss Roach’s pad, although they’d neglected to tell her they were doing this. Miss Roach, who already has a drug conviction, takes the rap while the boys get off scot-free. The narrator feels somewhat guilty about this but Dusty persuades him to let things be; although this does lead to Miller being dismissed with the following words:

Yes, he’d opened the door to the ‘Hip’ world for me all right. He’d shown me everything. I found the things I wanted to find, but now I wanted to find myself.

A conventional ending to an unconventional novel. That said the value of Baron’s Court, All Change emerges at least as much from the way in which it documents the emergence of the embryonic mod and hippie scenes, as from the story it tells. And all things considered, it is Taylor’s sense of style that carries the book, so I’d like to wrap up with another quote.

We put on a Jelly Roll Morton record (I’d ceased to think of him as a square) and listened a while very quietly and afterwards told each other how much we’d been missing when we thought of him as unhip as Karl Marx. Then Dusty let Diz have a blow on the gram, and he blew nice, having a right go at the drummer, hurrying him along, never letting him rest for a moment. Then his stable companion Charlie Parker gave him a rest and took over, knowing that these sounds were going to be played years and years and years and years later by cats who still thought of him as the Daddy of Them all.

It’s all here in this book, and what it reveals is a wild jumble of influences. Today’s mod fundamentalists may not like it but this is what mod looked and smelt like in 1960. Terry Taylor and his narrator were mods before mod, and simultaneously hippies in the making, while remaining at bottom beats; and the same might be said of my mother, Julia Callan-Thompson, who was part of Taylor’s inner circle in the sixties. These cats were hep, and Taylor’s book rocks! Baron’s Court, All Change had been hard to find until the new edition came out. It’s well worth seeking out. Essential reading for grooved out hipsters everywhere!

Further Reading

Teddy Boy Riots & Right-Wing Angry Young Men (Bernard Kops’ first novel)

Feature on 1970s British skinhead and hell’s angels novels

London Art Tripping: feature that goes into Taylor’s 1960s drugs and magic scene (among other things)

Dope In The Age Of Innocence

Books & Writing

Terry Taylor died in 2014 – here’s Ross Bradshaw’s appreciation of his life and writing