Jane McChrystal

In A Far Cry from Kensington envy and paranoia pervade the world created by Muriel Spark, where down-at-heel lodgers, failing publishers and unpublishable writers make their way through life in London nine years after the second world war. The entire city remains scarred by bomb damage, with its inhabitants trapped in a state of austerity not much improved since the end of the war.

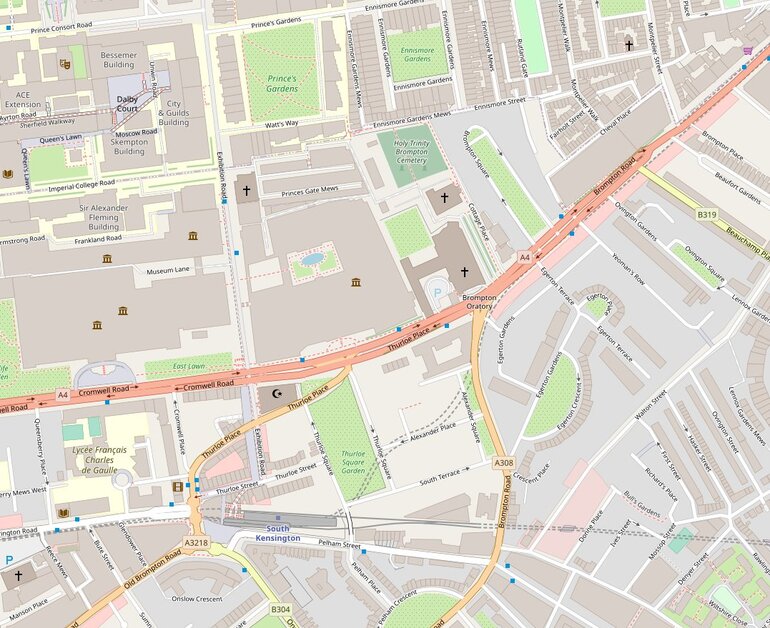

The novel is narrated from the point of view of Nancy Todd, as she recalls a time of her life, she seems glad to have left behind. Known then only as “Mrs. Hawkins”, she was an overweight twenty-eight year old widow, whose matronly demeanour and marital status relegate her to the role of confidant and advisor to everyone she knows. At the beginning of the novel she is living at Church End Villas just off the Brompton Road with her Irish landlady, Milly Sanders, and a motley assortment of boarders.

The smart stucco terraces with their columned porticoes which line the streets of South Kensington, were not always home to the wealthy individuals who live there today. In the 1950’s many of the houses were divided into bedsitting rooms, furnished with a stove and sink, where tenants shared bathrooms and toilets with neighbours on the same landing. Milly’s Church End Villa provides her lodgers with accommodation in an orderly house at a modest rent. Its aspect is one of suburban respectability:

The house was semi-detached, and on the detached side was separated from its neighbour by no more than three feet. There were eighteen houses on each side of the street, of identical pattern. The wrought-iron front gate led up a short path, with a patch of gravel and flower beds on either side and lined with speckled laurel bushes, to a front door which bore two panes of patterned glass.

The Brompton Oratory is close by, a handy place of worship for the many Polish Catholics displaced by the war who sought refuge in South West London. They include Wanda Podolak, one of Milly’s tenants, who pays the rent by mending and making her compatriots’ clothes on the sewing machine in her room.

Mrs Hawkins has a more prestigious occupation at the Ullswater Press where, despite lacking any formal qualifications or experience in publishing, she has made herself indispensable. She commissions authors and edits their work, as well as acting as a listening ear to Martin York, the head director of the press. In common with other gentleman publishers of the era, York’s company is on its last legs, thanks to his carelessness with money and a casual approach to business affairs.

The Ullswater Press transports Mrs.Hawkins from the shabbier milieu of Church End Villas to an elegant Queen Anne House in St. James, Mayfair, but not for long. First, she is fired from her position as editor with the Press and then finds another with Mackintosh and Turner in Notting Hill, which is even more short-lived. Finally, the editors of a poetry magazine in suburban Highgate offer her a more secure berth. During the break between the first two jobs, she experiences a state of dislocation, reflected in her observations as she wanders all over London on the top decks of buses:

to the farthest outskirts and termini. Stanmore, Edgware, Bushey, Chingford, Romford, Harrow, Wanstead, Dagenham, Barking. There were few streets intact although the war had been over ten years. Victorian houses, shops, churches were separated by large areas of bomb-gap. The rubble had been cleared away, but strange grasses and wild herbs had sprung up where war-demolished houses had been.

How did Mrs Hawkins reach this unhappy pass? It’s all down to the aspiring author, Hector Bartlett, who becomes obsessed with fulfilling his literary ambitions by using her as an intermediary. Bartlett waylays Mrs Hawkins on her daily walk through Green Park from Church End Villas to St. James Street, until she runs out patience and refuses to take the film script, he is trying to persuade her to present to Martin York, on the grounds that he is a “pisseur de copie”:

Hector Bartlett, it seemed to me vomited literary matter, he urinated and sweated, he excreted it.

Bartlett is in a relationship with popular novelist, Emma Loy, who, tiring of his company, wishes to disengage without stirring his vengeful streak, so she decides to promote his literary career as a distraction. First of all, Loy tries to rescue his reputation by asking Mrs. Hawkins to retract her accusation of “pisseur de copie”. She refuses and Loy has her fired immediately from the Ullswater Press.

Next, Bartlett submits “The Eternal Quest, a Study of the Romantic Humanist Position” to Mrs Hawkins’ second employer, Mackintosh and Toomey, and she is asked to put it “into shape”, which she refuses to do. Loy happens to be one of Mackintosh and Toomey’s most profitable authors. She calls a meeting with Mrs Hawkins and puts her under pressure to accept the editorial challenge of turning Bartlett’s book into something readable. Mrs. Hawkins will not comply and calls him “pisseur de copie” to Loy’s face. Her sacking follows swiftly.

Known for her good looks and a fondness for couture, Muriel Spark led the life of a celebrated author from the early nineteen sixties onwards, dividing her time between homes in New York and Italy, but her earlier days had not been easy. At one point in the fifties, while she worked in publishing and wrote her first novels, she was so poor that Graham Greene gave her an allowance to help her carry on. These years provided her with much of the material she drew on for her depiction of post-war London life in a A Far Cry from Kensington (1988) and The Girls of Slender Means (1963).

Born Muriel Camberg in Edinburgh in 1918, she was educated at James Gillespie High School, the model for Jean Brodie’s Marcia Blaine School for Girls. She seemed destined for a life of teaching or secretarial work until marriage in 1934 to Sydney Spark took her to Southern Rhodesia. Sydney proved unstable and prone to extreme mood swings, so she returned to England in 1944. She had a son, Robin, with Sydney whom she was unable to bring home until 1945, once she had achieved a measure of financial security which would enable her to support him. His upbringing was left in the hands of her parents in Edinburgh. Their adult relationship foundered on differences in religious belief; Spark was a convert to Catholicism, while Robin stuck to the Jewish faith he grew up with. Sadly, they remained estranged until the end of her life. Spark found stability with her companion of thirty years, the artist Penelope Jardine, and ended her days cared for by her in a Tuscan rectory, where she died in 2006.

Born Muriel Camberg in Edinburgh in 1918, she was educated at James Gillespie High School, the model for Jean Brodie’s Marcia Blaine School for Girls. She seemed destined for a life of teaching or secretarial work until marriage in 1934 to Sydney Spark took her to Southern Rhodesia. Sydney proved unstable and prone to extreme mood swings, so she returned to England in 1944. She had a son, Robin, with Sydney whom she was unable to bring home until 1945, once she had achieved a measure of financial security which would enable her to support him. His upbringing was left in the hands of her parents in Edinburgh. Their adult relationship foundered on differences in religious belief; Spark was a convert to Catholicism, while Robin stuck to the Jewish faith he grew up with. Sadly, they remained estranged until the end of her life. Spark found stability with her companion of thirty years, the artist Penelope Jardine, and ended her days cared for by her in a Tuscan rectory, where she died in 2006.

Between 1944 and 1954 she worked in publishing, including a spell as the first female editor at the Poetry Review, where she gained her insight into the poisonous, post-war London literary scene. Like Mrs. Hawkins, Spark spent many working hours rejecting writers who never stood a chance of being published. While editorial jobs were fairly poorly paid at the time, they also carried a certain cachet. Consequently, they were much sought after by nicely brought up young women who had wealthy parents and no need to rely on a meagre salary. Spark had no such backing.

In A Far Cry from Kensington things are frequently not what they seem and Spark’s preoccupation with this theme, reflected throughout her oeuvre, had its origins in the time she spent during the war working for MI6. For a start, Martin York turns out to be a criminal rather than the amiable war hero and incompetent businessman his employees have taken him for and ends up in prison for six years with a conviction for forgery and fraud. Mrs. Hawkins, too, reveals over half-way through the novel that the image of grieving widow she projects is very much at odds with the story of how she lost her husband.

Spark’s time in MI6 during the second world war formed the foundation of the darkest plot strand in A Far Cry from Kensington, which involves Wanda Podalok. Spark worked on the “double Cross” system at MI6, which flooded the German airwaves with fake news, designed to demoralise the population, exacerbate pre-existing divisions within German society and generally undermine the war effort. In A Far Cry from Kensington a cult-like organisation captures Wanda, by preying on her fear that the British government could pick her up at any moment and deport her to Poland. They make cryptic telephone calls and shower her with forged letters, newspaper cuttings and photographs to persuade her to operate an electronic box which, they believe, can be used to exert power for good or ill over others, with or without their knowledge. Their fake narrative is so powerful that it induces a delusional state in Wanda and ends in tragedy. These sinister activities lend a surreal edge to the novel in contrast to its realistic setting, a device employed by Spark in a number of her other works and the source of much of her originality. It’s a pity, then, that her novels seem less highly rated now than those of authors such as Greene and Waugh, with whom she was compared favourably in her day.

Spark’s concise, witty prose is the perfect vehicle for her rather chilly view of humanity. At times, she disposes her characters with a dispassion verging on cruelty, but her Catholic faith adds a more humane dimension to her work; some are allowed to exercise free will and transform their lives. In A Far Cry from Kensington Mrs. Hawkins resolves to eat half of everything on her plate at every meal. In shedding her protective sheath of flesh, she reveals she is more than just a receptacle for others’ woes and starts a relationship with the man whom she will marry. Spark’s faith in the lasting value of friendship and loyalty are illustrated by the bond between Mrs. Hawkins and her landlady, Milly Sanders. These two women, so different in age, class and background, offer each other comfort and support as the dramatic events of the novel roll out, and their friendship endures long after Mrs. Hawkins has left Milly’s house.

Jane McChrystal is an independent researcher and writer based on the Isle of Dogs. She writes about a wide variety of cultural and historical subjects, with a particular interest in the history of the East End of London. Her book The Splendid Mrs. McCheyne and the East London Federation of Suffragettes will be published by The Choir Press in August 2020.

All rights to the text remain with the author.