Andrew Whitehead

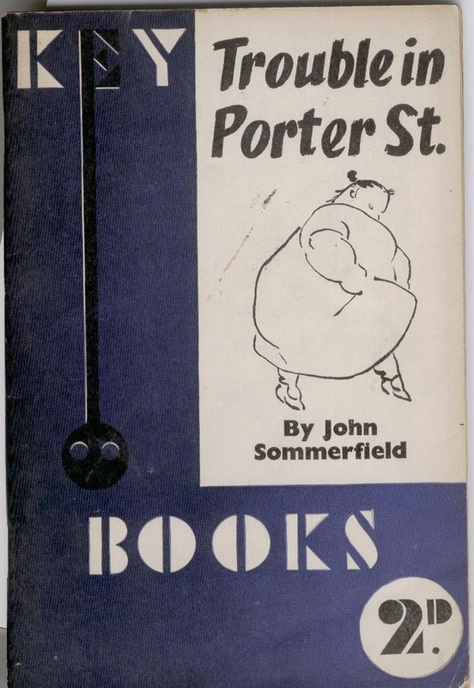

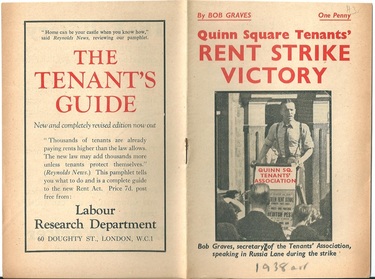

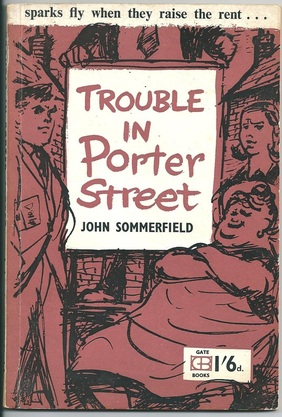

When John Sommerfield was asked by the Communist Party to write a pamphlet explaining how to organise a rent strike, he produced not a manual but a short story. It was called Trouble in Porter Street, was priced at a very affordable tuppence (that’s under 1p in decimal money – and allowing for inflation is the equivalent of not more than 50p today), and sold in the tens of thousands.

It’s agitprop literature, of course. How could a story that carries on its closing page the battle cry: “Hurrah for the Communist Party!” be anything else. But that is part of the delight of Trouble in Porter Street (1939) – an overlooked gem, very much a product of the moment, written as a guide to how best to organise a tenants’ movement. It’s a political primer in pamphlet form, an account of a housing struggle in a working class street in an unspecified corner of London.

Sommerfield was an accomplished writer, and he brings to Porter Street a gift for dialogue, narrative and basic characterisation. It was his most telling and affectionate account of a working class community – a theme he returned when he wrote North West Five (1960), a novel set in post-war Kentish Town, by which time he had broken with the Party.

Sommerfield was an accomplished writer, and he brings to Porter Street a gift for dialogue, narrative and basic characterisation. It was his most telling and affectionate account of a working class community – a theme he returned when he wrote North West Five (1960), a novel set in post-war Kentish Town, by which time he had broken with the Party.

John Sommerfield was a Londoner, born in 1908 and brought up near Portobello Road. He was sent to a fee paying school, but left at fifteen, went to sea, wrote a tolerably successful book based on his experiences, and in his early twenties joined the Communist Party. The party was to form a very large part of his life for the next quarter-of-a-century. He got to know other left-wing figures on the literary scene such as Randall Swingler, Edgell Rickword and Maurice Cornforth. Sommerfield fitted in well to this hard drinking, disputatious sub-culture.

By the age of thirty, Sommerfield had written the two books for which he is remembered. May Day – first published in 1936 – is an experimental-style novel set over three days leading to a May Day demonstration in London. He described it many years later as ‘early ’30s Communist romanticism’. Volunteer in Spain came out the following year. It’s his account of fighting on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War and captures the tedium and confusion of conflict as well as the camaraderie. In later years, he wrote, made short films, and mixed in literary circles – he sought to recruit Doris Lessing to the Communist Party Writers’ group – but never achieved the success and standing to which he aspired.

Trouble in Porter Street reflects a turn by the Communist Party towards tenants issues, and is a powerful reminder that for a couple of decades either side of the Second World War, housing was London’s big political issue. The party had been actively involved in rent strikes in the East End where – according to Phil Piratin, later Communist MP for Stepney and Mile End – it was looking for grassroots issues to help build on the success of its anti-fascist activity, culminating in the ‘Battle’ of Cable Street in October 1936.

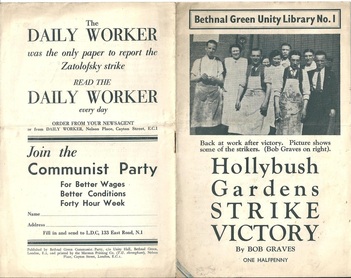

Taking up tenants concerns which affected sympathisers of the Mosleyites as much as anyone else was seen as a way of weaning support away from organised fascism. The Stepney Tenants’ Defence League, which is mentioned in Porter Street, was viewed as a model of party campaigning on housing, broad-based but largely under the leadership of party members.

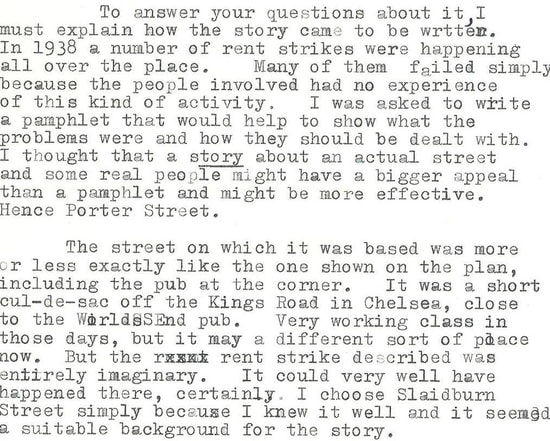

In his story, John Sommerfield doesn’t precisely locate Porter Street. But it doesn’t have an East End feel to it. There’s nothing about the Docks, or Cable Street, and while there are Jewish characters it’s clearly not set in or close to a Jewish area. It prompted me to write to John Sommerfield (who died in 1991) about how he came to write the pamphlet and where he had in mind as the setting. Here’s what he said:

The writer and literary historian Andy Croft knew John Sommerfield and admires his writing–and once asked him to explain the background to Trouble in Porter Street:

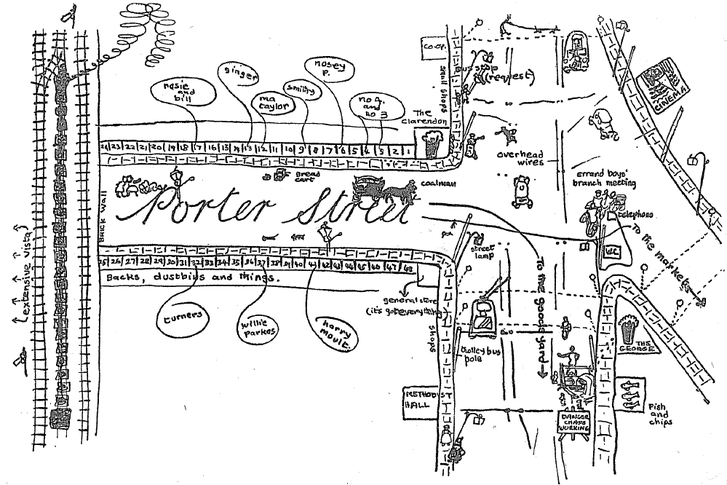

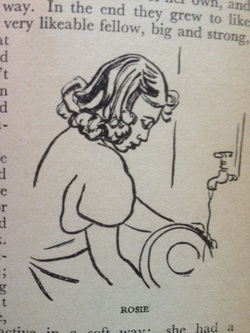

From the start Sommerfield presents Porter Street as a fairly self-enclosed community. It’s a cul-de-sac (as Slaidburn Street is – there’s more about the street at the bottom of this page), with Victorian houses subdivided into a family on each floor. The faultine in the street is between the market traders (the sort of occupation sometimes sympathetic to Mosley) and railway workers (more often seen as the backbone of the organised working class). The drawings by Sommerfield’s wife, Molly Moss, are one of the delights of the story – simple, at times tender, and full of humour, as you can see from her map of the street.

Porter Street (Sommerfield writes) was marked off from dozens of similar dingy little streets in the neighbourhood by having a blank wall at one end, behind which trains rattled and roared all day. Because it was a blind alley there was little traffic and the road formed a splendid playground for the children.

There were forty-eight two-storied houses in the street, each of which looked exactly like the next one. Each row was simply a long brick wall into which doors and windows were pierced. Three families inhabited some of the houses, and two the others. Many had lived there for several generations, and some had inter-married within the street.

Rosie Dixon, when she marries, simply moves from one side of the street to the other. Her family are market traders; her husband, Bill, is a railwayman working at the goods yard. So she brings together the two sides to the ‘old feud’ which from time-to-time erupts along Porter Street. Her home is two rooms and a scullery on the ground floor, and they pay 14s 10d (that’s about £0.75) a week to the Housing Finance Trust, owned by ‘a sallow, middle-aged, nervous little gentleman called Levine, who lived in a steam-heated baronial mansion in apart of Sussex almost entirely populated by people with incomes of more than five thousand a year‘.

One engaging aspect of Trouble in Porter Street is this choice of Rosie as a central character, and its depiction of the difficulties of the working class housewife – making ends meet, keeping the house clean, hoping to afford a holiday, worrying about starting a family, the struggle to maintain standards and some respectability: ‘No wonder some failed in it, no wonder that in the windows of a few of the houses grubby, ragged lace curtains concealed frowsiness, unwashed rags and pots, sour smells of dirt and poverty. But on the sills of many windows were flower boxes, in front rooms the cold greenness of apisdistras reared itself, and doorsteps were scrubbed and hearthstoned continually.’

One engaging aspect of Trouble in Porter Street is this choice of Rosie as a central character, and its depiction of the difficulties of the working class housewife – making ends meet, keeping the house clean, hoping to afford a holiday, worrying about starting a family, the struggle to maintain standards and some respectability: ‘No wonder some failed in it, no wonder that in the windows of a few of the houses grubby, ragged lace curtains concealed frowsiness, unwashed rags and pots, sour smells of dirt and poverty. But on the sills of many windows were flower boxes, in front rooms the cold greenness of apisdistras reared itself, and doorsteps were scrubbed and hearthstoned continually.’

The story explores the rituals of the street – weekend shopping, the Sunday joint, the pub, the raffles, the gossiping at the doorstep.

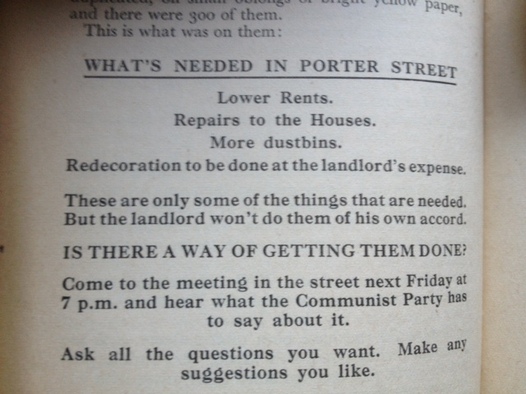

Into this insular street culture comes the Communist Party, picking up on latent dissatisfaction about high rents and next-to-no repairs. They are presented as outsiders who have to navigate their way carefully and win the confidence of Porter Street. Mike Bloom and his comrades hand out leaflets about rent control and sell the ‘Daily Worker’ door-to-door:

“I get it down the yard sometimes,” Bill said to Mike Bloom. “Mind you, I don’t say I’ll take it regular, but you can always leave one for me when you come round. I don’t ‘old with a lot it says, but it’s a paper that speaks out straight.”

“What about the railways?” the young fellow asked. “Whose side does it give – the companies’ or yours?”

…

“I’m an ordinary working man,” said Bill Dixon. “I don’t take much notice of politics. Course, I always go down and vote for the Labour man at the elections -”

“But don’t you see, your own conditions ‘re politics. Rents ‘re politics.”

“They’re too bloody ‘igh round ‘ere, I know that,” said Bill.

The purpose of the story is to demonstrate how the Communists turn Porter Street’s anger about rents and repairs into a campaign, and a victory over the landlord. Woven into the story are accounts of leaflets (a couple are quoted in full), street meetings, platform oratory, and organising to frustrate the debt collectors and bailiffs. A Tenants’ League is set up, encouraged by rent strike victories in Bethnal Green, and the rents are brought down. Very few Porter Street residents join the CP, but several – Rosie Dixon among them – become sympathetic and join the Tenants’ League committee, surprising themselves by their political boldness.

The purpose of the story is to demonstrate how the Communists turn Porter Street’s anger about rents and repairs into a campaign, and a victory over the landlord. Woven into the story are accounts of leaflets (a couple are quoted in full), street meetings, platform oratory, and organising to frustrate the debt collectors and bailiffs. A Tenants’ League is set up, encouraged by rent strike victories in Bethnal Green, and the rents are brought down. Very few Porter Street residents join the CP, but several – Rosie Dixon among them – become sympathetic and join the Tenants’ League committee, surprising themselves by their political boldness.

‘… the position of the Communists as outsiders had changed. There was a tacit acceptance of them, they were no longer looked on either as well-meaning or interfering strangers.’

When the campaign is successful, a victory meeting is held at the pub at the end of the street:

A record crowd filled the Clarendon. The Committee could have drowned themselves in all the beer that was offered to them. A good slice of the first week’s reductions went down people’s throats that night.

Said Bill: “Another thing – after this there needn’t be any more talk of the market chaps and the railway men being against each other.”

Rosie said: “Now we’ll be able to save up for our ‘oliday.”

Smithy said: “Hurrah for the Communist Party! They’re the lads.”

Harry Moult said: “Gorblimey! Now my ole woman ‘ll go and get a wireless on the never-never,”

Bob Douglas said: “The next step is to get a proper agreement about repairs and redecorations. And we must start spreading the movement to other streets.”

Everyone had something to say. The victory meant something a little different to all of them. They all had something new to look forward to, and everyone had learned something that they would never forget.

Some aspects of Trouble in Porter Street strike a discordant note. Take the account of Mrs Nicholl, ‘the mysterious and rather beautiful half-caste woman who lived at Number 23 … She passed him without a glance, her walk elegant and graceful on slim legs. … Nice tart, he remarked to himself.’ When the pamphlet was republished in 1954 – and at nine times the original price – the attitudes to gender survived unchanged. Some of the antipathy to Jewish slum landlords was modified, however. The owner of the Housing Finance Trust was renamed – no longer Issy Levine, but Mr Smallbone.

Some aspects of Trouble in Porter Street strike a discordant note. Take the account of Mrs Nicholl, ‘the mysterious and rather beautiful half-caste woman who lived at Number 23 … She passed him without a glance, her walk elegant and graceful on slim legs. … Nice tart, he remarked to himself.’ When the pamphlet was republished in 1954 – and at nine times the original price – the attitudes to gender survived unchanged. Some of the antipathy to Jewish slum landlords was modified, however. The owner of the Housing Finance Trust was renamed – no longer Issy Levine, but Mr Smallbone.

Sommerfield provided an additional chapter taking Porter Street from 1938 to 1954. In the intervening years the street had got shabbier. Its residents had survived the war and become disillusioned with what a Labour government had made of the peace. Smithy was still in the CP, but there didn’t seem to be a lot of fire to his activism. A fair reflection, you might say, of the changing times.

Andrew Whitehead is a historian and journalist and the founder and moderator of the London Fictions website.

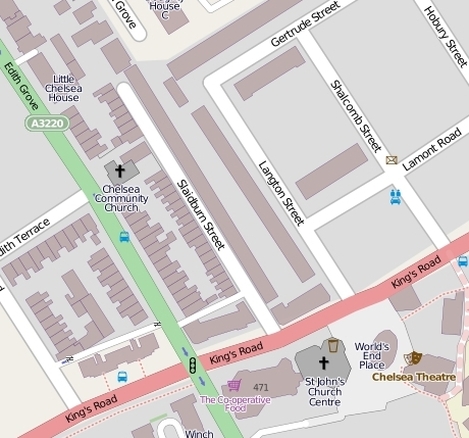

Near World’s End – the real Porter Street

Slaidburn Street is a cul-de-sac just off the King’s Road – on the less fashionable side of Chelsea, not that anywhere in this quarter of London is exactly down-at-heel. The houses are imposing, on three floors, but compact.

It’s about the only corner of Chelsea where you stand a chance, just a chance mind you, of getting a Victorian house for less than a couple of million. Slaidburn Street ‘has always been considered the poor relation of Chelsea’, an estate agent declared back in 2004. Not that poor nowadays, to judge by the smart cars and roof gardens.

It’s about the only corner of Chelsea where you stand a chance, just a chance mind you, of getting a Victorian house for less than a couple of million. Slaidburn Street ‘has always been considered the poor relation of Chelsea’, an estate agent declared back in 2004. Not that poor nowadays, to judge by the smart cars and roof gardens.

The street was built initially as a short stub of houses in about the 1860s, close to Cremorne Gardens which flourished as one of London’s most popular pleasure gardens. It was, by reputation at least, a red light area.

The closure of Cremorne Gardens in 1877 seems to have done little to salvage Slaidburn Street’s standing. In the Booth survey at the end of the century, the street stood out as being coloured black, representing the lowest of the seven social categories. In the survey’s notebooks, Slaidburn Street is described as ‘a cul-de-sac, asphalt-paved, one of the worst streets in Chelsea and I should say one of the worst in London – drunken, rowdy, constant trouble to police: many broken patched windows, open doors, drink-sodden women at windows.’

The pattern of multiple occupation described in Trouble in Porter Street – with two or three households to each house – appears to have persisted into the 1960s and ’70s. General Sir Roy Redgrave, whose account of the street in which he lived is posted below, remembers the last of the houses with outside loos and no bathroom being modernised in the ’80s.

The blank wall at the end of the street doesn’t hide a railway line, as in Porter Street, but simply seems to have been a curiosity of estate development in the area. It may have been to quarantine neighbouring streets from Slaidburn Street’s undesirable reputation. Who knows!

The pub at the end of the street in Sommerfield’s account, ‘The Clarendon’, was indeed a local boozer – but was later done up, became known as Swift’s but is now (late 2012) a Paddy Power bookmaker. On the opposite corner is a gentlemen’s barber shop. And on the south side of King’s Road, just opposite Slaidburn Street, is a Cooperative supermarket.

The street seems to have survived the Second World War largely unscathed. There is some infill housing suggesting bomb damage, but Slaidburn Street fared a lot better than much of Chelsea’s World’s End (the district is named after a pub) which got hit badly in the Blitz. The World’s End estate, just across the road, was built in the 1960s and ’70s on the site of Cremorne Gardens, and is less gentrified than you might expect given the address.

Andrew Whitehead, 2013

Click below to hear General Sir Roy Redgrave, a resident of Slaidburn Street, talking about the street’s history and the echoes of ‘Porter Street.’

References and Further Reading

John Sommerfield – They Die Young, 1930

John Sommerfield – May Day, 1936, republished by Lawrence and Wishart in 1984 with a new preface by the author and an introduction by Andy Croft, and again republished by London Books in 2010 with an introduction by John King

John Sommerfield – Volunteer in Spain, 1937

John Sommerfield – North West Five, 1960

Andy Croft – ‘Returned Volunteer: the novels of John Sommerfield’, London Magazine, April/May 1983

Sarah Glynn – ‘East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing: a comparative study of political mobilisation in the Jewish and Bengali communities’, available online here

Nick Hubble – ‘John Sommerfield and Mass-Observation’, The Space Between: Literature and Culture, 1914-1945, 8:1, 2012, pp.131-51

Phil Piratin – Our Flag Stays Red, 1948

James Purdon, ‘The Early Fiction of John Sommerfield’, Oxford Handbooks Online, 2015

Andrew Whitehead – ‘John Sommerfield’s Box’, Literary London Journal, Spring 2014, available online here

Many thanks to Pete Sommerfield for permission to quote from his father’s writings and make use of illustrations by his step-mother, Molly Moss.

And warm thanks to Andy Croft of Smokestack Books for allowing an extract from his interview with John Sommerfield to be posted here.

Details of John Sommerfield’s archive are posted online here.

All rights to the text remain with the author.