Philippa Thomas

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

Zadie Smith’s London exhausts me. It’s relentless and remorseless. The London of NW traps you, grinds you down, never lets you go.

It’s weighed down by the tensions of class, of race and of casual violence. The in-your-face realities of curses and coarseness. It’s strange to write this in the afterglow of London’s Olympic summer. But perhaps Zadie Smith’s vision is a corrective to those weeks of communal euphoria.

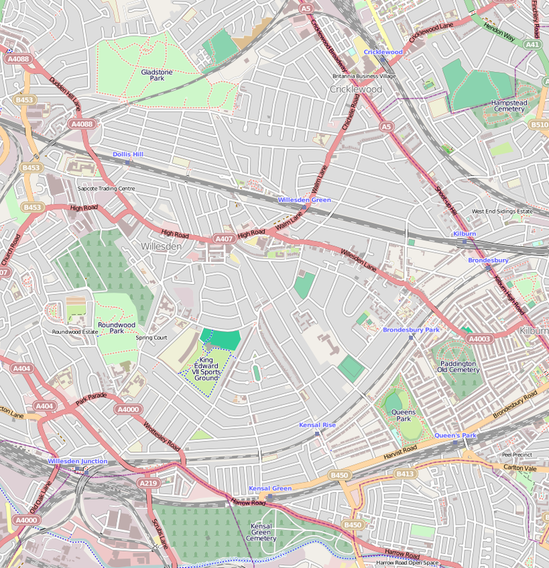

The novel revolves around the fictional Caldwell estate, but its setting is real. She gives us both Kilburn’s skyline, ‘ungentrified, ungentrifiable’, and the pretensions of the posher bits of Willesden, ‘little terraces, faux-Tudor piles’. There’s some space for maneouvre but not much. Like her characters, we rarely get out of this two-mile square of the city for long.

Of the three key figures, we begin and end with the girls: Leah of Irish descent; Keisha, Jamaican. They ‘went Brayton’ together, to the ‘thousand-kid madhouse’ of the local primary school. The story of Felix flares up and flames out in between them. In different ways, all three try to move on. They’re all brought back or brought down. Smith’s NW isn’t a land of opportunity.

From the beginning, the writing makes me claustrophobic. Leah is in the garden, superficially free and easy, swinging in her hammock. But she’s in the garden of a basement flat. ‘Fenced in, on all sides’, and already oppressed by the sound of a string of curses from a neighbour’s balcony. “It ain’t like that. Nah it ain’t like that. Don’t you start.”

Leah does start. She goes to college, ‘a state-school wild card’, ‘the graduate’, but as an adult, comes home. We meet her partner, Michel – French Algerian – one of the few men in the book determined to get a sweeter life. His ambition would make Margaret Thatcher proud: to move on from the council flat into ‘a proper flat, a mortgage’. He has a dream. “If we ever have a little boy I want him to live somewhere – to live proud – somewhere we have the freehold.”

But Leah can’t. Where she works for a community charity, the only white girl in the office, she’s teased every day for taking one of ‘their’ men. She can’t move on. She can’t face getting pregnant, and she ends it – again. We last see her back in the hammock, dazed, defeated, getting blistered by the sun.

But perhaps she didn’t see the point of change. This is what she knows. ‘Leah, born and bred, never goes anywhere’.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=elTj2cmH8wA

Our second protagonist knows that too, but he’s pushing to get beyond it.

In his section, NW6, we join Caribbean Londoner Felix Cooper on a journey to the West End – travelling by tube, Kilburn to Baker Street, Baker Street to Oxford Circus. We look through his outsider’s eyes at the discreet gleam of wealth on the side streets, ‘slick black doors, brass knobs, brass letterboxes’. We meet the callow posh boy Tom, selling off a car for his father, quite unable to treat his potential buyer on equal terms. Shocked that Felix is black. Asking if he has any dope.

But we also learn, incidentally, about Felix’s roller coaster ride through London life – adventure, drugs, descent, and now a sense of mission. He’s going to escape the world of ‘sitting on concrete steps in a stairwell somewhere on Caldwell estate’. ‘Start all over again, fresh’.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TrKL2NopdJc

But for the alert reader, Felix’s end has already been foreshadowed in a briefly mentioned news event before we even meet him.

The incident that for Felix is the beginning of the end made me shudder, and put down the book. He’s on the Tube, heading home, daydreaming. And in one fell swoop, he’s stereotyped – by the pregnant white women who assumes he’s with the black guys opposite – he acts – “your man’s got his feet on her seat, blud” – and he’s targeted – all because of the colour of his skin. Smith absolutely captures the body language of the London Underground, fleeting glances full of meaning.

In Zadie Smith’s book, there’s one explicit allusion to the death of Stephen Lawrence – the black teenager infamously stabbed to death at a bus stop in South London. It adds to the sense of low level threat that seeps through the pages. But Felix meets danger not at the hands of a gang of racist white youths – but one of his own.

The world of NW isn’t simplistic. It’s more confusing than that. There are all sorts of racial currents, reflecting the ebb and flow of different communities. A young Sikh runs the corner shop. The quiet old Anglican church now gathers a congregation of ‘Polish, Indian, African, Caribbean’. Women ‘from St Kitts, Trinidad, Barbados, Grenada, Jamaica, India, Pakistan’, doll themselves up for a warm night out on the Edgware Road. Leah’s mum thinks about the ‘wily Nigerians’ ‘owning things in Kilburn that once were Irish’. She ‘looks pointedly towards their old estate, full of people from the colonies and the Russiany lot’. Leah’s Michel says “I’m not like these Jamaicans [who] still have no curtains. I am an African. I have a destiny.”

Zadie Smith layers on the detail convincingly – sight, sound, smell. ‘Sweet stink of the hookah, couscous, kebab, exhaust fumes of a bus deadlock.’ At one point, she speaks to the reader, inviting us in. ‘A local tip: the bus stop outside Kilburn’s Poundland is the site of many of the more engaging conversations to be heard in the city of London. You’re welcome’.

But her book also gives a nod to the getaway postcodes – the places her characters mention fleetingly, with envy or with longing. We hear that ‘Wimbledon’ is the countryside, ‘Pimlico’ pure fiction. The Khan kid tells Felix “I’m in Hendon now, innit”, speaking ‘a little bashfully, as if it was too much good luck to confess to’.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lApuWxG8JJM

The real character with destiny, the book’s success story, seems to be Keisha Blake – Leah’s best friend from school – a girl who’s on the move and on the make. At university she’s ‘crazy busy with self-invention’. She becomes Natalie de Angelis. She becomes a barrister, practising commercial law. She lives in the London world of those who’ve made it. One perfect husband, two perfect children, one fabulous house (‘twice the size of a Caldwell double’.) ‘Private wards. Christmas abroad. Security systems. Fences. The carriage of a 4×4 that lets you sit alone above traffic.’

But she’s hollowed out by the effort of playing a part, and we follow her spiralling down, losing it. I didn’t quite believe the speed of her slump. It felt to me as if the structure of the novel demanded she pay the price. But it does lead us to another stretch of London entirely.

For most of Zadie Smith’s novel, I felt pulled down as a reader, forced to idle in the basement flat, to hang out on street corners and at bus stops and in the ‘boxy cramped Victorian damp’ of Leah’s crowded office space. One Caldwell character, the old man Tom, talks about Londoners needing their bit of green, but there’s precious little of it here.

There are two memorable scenes where the horizon lifts. But they’re both about false promise. At the top of a flight of stairs in Soho, Felix visits an old flame Annie. She’s stuck in her own life, stupid with booze and coke. They head up through the trap door to the roof where he worked with a film crew in more glamorous days. There’s a view. He tries to match it, talks about getting on with his life. But it’s a squalid meeting – they grapple through sex, a clumsy shag – and as they look out at a man and a woman and a toddler trying to picnic on a nearby terrace, Annie loudly mocks the aspiring happy family. In a way, it’s very funny. But cruel. So much for that.

Back then to Natalie’s journey – or Keisha’s, as she walks out of her life and drops back in, via the Caldwell estate, with her old class mate Nathan Bogle. The boy who was so fine at ten is now an addict and a wreck: a man whom it emerges is running girls and ruining lives.

They head out and up, climbing the ‘great hill’ that begins in Willesden and ends in Highgate. ‘They crossed over and kept climbing, past the narrow red mansion flats, up into money’. Stumbling up to a beautiful corner of London. Up to the top of Hampstead Heath. But even this scene is written as if they’re the outsiders. They’re depicted like animals, scurrying, creeping, crouching to piss in the woods.

Follow their tracks to the top of the hill and all of London is out there. But it’s not there for them. The author demands her characters retreat.

Philippa Thomas is a BBC news journalist who’s lived in different corners of London for much of the last twenty years. She’s currently to be found in N7, off the Holloway Road. She blogs at www.philippathomas.com and tweets @Philippanews.

Links and Further Reading

Zadie Smith – White Teeth (2000) – an appreciation by Lisa Gee

– The Autograph Man (2002)

– On Beauty (2005)

YouTube videos originally posted by Penguin USA

All rights to the text remain with the author.