Anne Witchard

China in the Western imagination has long been both the repository of fantasy and a mirror of our disquietudes. In the early twentieth century Sax Rohmer created the fiendish Dr Fu Manchu as the epitome of Chinese threat, ‘the yellow peril incarnate in one man’ intent on nothing less than the downfall of Western civilization.

Even beyond its cohort of unrepentant fans and equally vociferous detractors, Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu series (beginning in 1912) sustains a cultural longevity that merits our attention. That this dated generic phenomenon has now outspanned the century of its birth might be attributable to the fact that Rohmer’s super villain actually has his imaginative genesis in the 1890s. The closing decade of the Victorian era is redolent with metropolitan associations that remain iconic: Hansom cabs and Sherlock Holmes, mummy curses and murky gaslight, a visiting vampire count and Jack the Ripper.

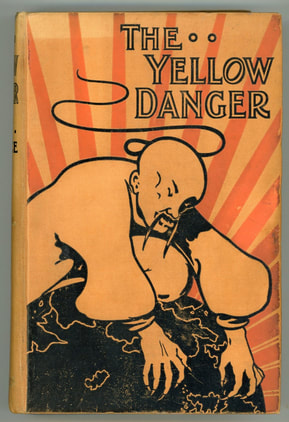

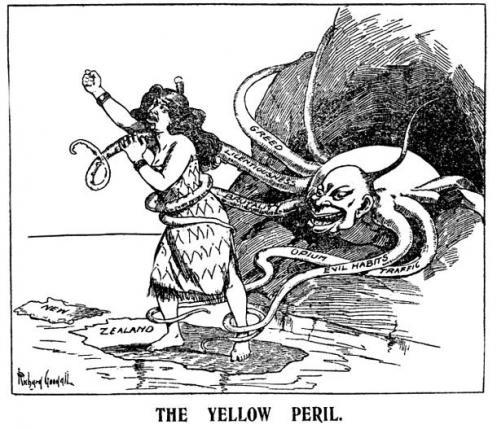

We might date the start of an obsession with a Yellow Peril in British popular culture from 1898, its most notable marker being the publication that year of M. P. Shiel’s novelThe Yellow Danger.

We might date the start of an obsession with a Yellow Peril in British popular culture from 1898, its most notable marker being the publication that year of M. P. Shiel’s novelThe Yellow Danger.

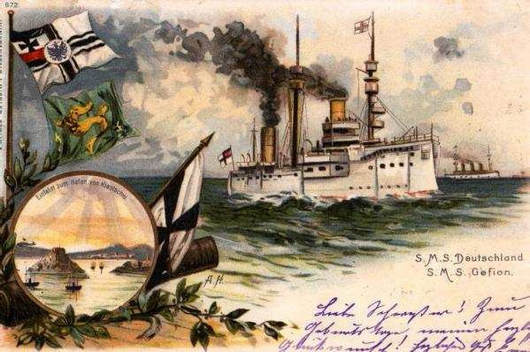

Shiel had worked this up at the request of publisher Grant Richards from a weekly serial, The Empress of the Earth: The Tale of the Yellow War, fired off a few months earlier for publisher C. Arthur Pearson’s Short Stories magazine after‘some trouble broke out in China’. The ‘trouble’ to which he referred – what became known as the Kiaochow incident – looked set to topple Britain’s dominating influence among the European nations in China as, after China’s surprise defeat by the Japanese in 1895, the Western powers engaged in an increasingly ignominious squabble over treaty concessions and spheres of influence.

In November 1897, the killing of two missionary priests provided a handy pretext for Kaiser Wilhelm to dispatch a couple of warships to the port city of Kiaochow (now Jiaizhou). Tsar Nicholas responded by seizing Port Arthur (now Lushun). Russia had by now pushed the Trans-Siberian Railway across Manchuria and built a branch line to Port Arthur on the Yellow Sea. Then France occupied Hainan Island in the South.Thus began what is known as the Scramble for Concessions.

It was this diplomatic crisis that prompted Pearson, to capitalize on public interest and commission The Empress of the Earth.It was not just that manoeuvres between the Continental powers looked set to oust England’s long held predominance in China, it was feared that the German action, imitated by others, might push China into military collusion with Japan against the West. This was a fearsome prospect indeed.The Empress of the Earth ran weekly in Short Stories(5 February – 18 June 1898), each chapter incorporating actual headline events as the crisis unfolded. The series proved wildly popular with the public.

Pearson’s company had not only motivated a recent crop of future war stories (the popular genre of hypothetical invasion fiction had begun in 1871 with the runaway success of George Tomkyns Chesney’s The Battle of Dorking), but had been editorially specific about which territories were to be conquered and by whose armies. Because Pearson paid well for his stories he called the shots, perhaps even directing the outcome of H. G. Wells’ series The War of the Worlds (begun in 1897).The Empress of the Earth was Shiel’s first major serial and he was in no financial position to call his own shots. Each week he interwove stories from the previous week’s news events into a fantasy of future global war. England, with no allies and enfeebled by ‘the rapacity and selfish greed of her competitors’ (namely Russia, Germany and France), lay vulnerable to an approaching ‘locust swarm of the yellow races’.Pearson responded to the success of the series by ordering Shiel to double the length to 150,000 words. Shiel cut it back by a third for Grant Richard’s book version, which was rushed out that July as The Yellow Danger.

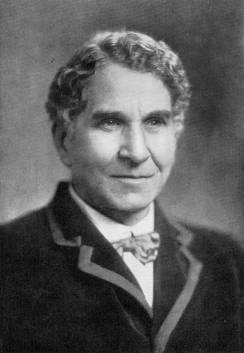

Matthew Phipps Shiel (1865-1947) had come to London in 1885 from his native Montserrat, one of the smaller Caribbean islands. Given the preoccupation of his later work it comes as some surprise that Shiel was of mixed-race parentage on both sides,something he chose to keep hidden, claiming when asked about his racial origins to be of solely Irish descent.Without formal qualifications or financial backing Shiel turned to his pen for support, and found himself on the fringes of literary Bohemia. He was vaguely acquainted with Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Symons and Oscar Wilde. Closer friends included Arthur Machen and Decadent poets Theodore Wratislaw and Ernest Dowson, with whomhe roomed for a while in the late 1890s at 1 Guilford Place, Bloomsbury, sharing a taste, too, for Music Hall and little girls. In the mid-Nineties, Shiel was staying at the evocatively named 41 Coldbath Chambers on Rosebery Avenue where Machen was a close neighbour.

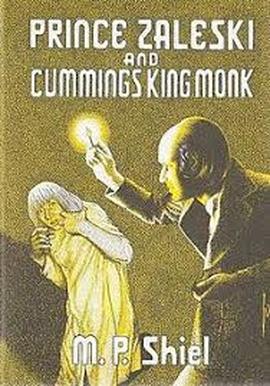

Shiel’s early literary reputation was formed by two collections of short stories for maverick Yellow Book publisher, John Lane’s Keynote series. The stories, strongly influenced by Edgar Allan Poe,were written in the purplest of prose, redolent with the fumes of hashish and furnished with frontispieces by Aubrey Beardsley. Prince Zaleski (1895) was No 7 in the series and another, Shapes in the Fire (1896), would be No 13. Machen’s novella The Great God Pan (1894) and The Three Imposters (1895) appeared in the same series. Machen’s Keynote works are now established classics of Victorian London Gothic while Shiel’s, stylistically the most quintessential of Decadent texts, are pretty much forgotten. But Machen envied Shiel’s abilities,writing admiringly: ‘his stories tell of a wilder wonderland than Poe dreamed of’ and Shiel remembered that ‘Machen said I had done what he had always aspired to do’.

The fate of the short-lived English Decadent movement had been sealed by Wilde’s conviction, its repercussions preventing any further possibility of publishing the kinds of books the Bodley Head had championed. But just as John Lane was cutting his riskier authors loose, Shiel’s popular reputation began to be established.

The fate of the short-lived English Decadent movement had been sealed by Wilde’s conviction, its repercussions preventing any further possibility of publishing the kinds of books the Bodley Head had championed. But just as John Lane was cutting his riskier authors loose, Shiel’s popular reputation began to be established.

The thrust of The Yellow Danger revolves around a conspiracy to oust England from her ‘natural’ predominance in China,its jingoism underscored with the rhetoric of Christianity: England ‘having a genuine supremacy of racial value and valour’ must ‘like the Christ of the nations, with many an agony of sweat and blood, redeem mankind’. Shiel didn’t shy away from the horrors Europe might expect at the mercy of a conquering Orient: ‘The reign of hell which had followed upon some Japanese victories during the Sino-Japanese War was well known in Europe. If China had fared so at the hand of Japan, how would Europe fare at the hand of China led by Japan?’Racial antagonism, even if it wasn’t underscored by Pearson’s editorial, was certainly what readers expected.

Much has been written about Sax Rohmer’s debt to M. P. Shiel regarding the genesis of the character of Dr Fu Manchu in The Yellow Danger’s mastermind, Dr Yen How. As it was Shiel’s agenda to incorporate real events and people we can trace some of the (less diabolic) characteristics of Yen How to the Chinese revolutionary, Dr Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925), then making headlines in England. In 1896 Sun was detained by the Qing Secret Service and held captive for twelve days in London’s Chinese embassy on Portland Place. Were it not for a high profile media campaign led by Sir James Cantlie, his former Hong Kong medical school lecturer, Sun would have been shipped back to China and beheaded. Many notables of the day get actual name-checks in The Yellow Danger, including an array of British aristocrats and politicians as well as the Irish Nationalist MP and newspaper publisher, T. P. O’Connor, the British Minister in China, Sir Claude Macdonald and Sir Robert Hart, the Inspector-General of China’s Imperial Custom Maritime Service.

The resonations of The Yellow Danger, in spawning the legend that is Fu Manchu, have long overshadowed the political and diplomatic machinations of its historical moment. In order to better comprehend Fu Manchu’s longevity then, we might return to the cultural complexities of the Yellow Nineties and the ways in which Shiel’s extraordinarily strange writing encapsulated these ideological and socio-cultural shifts.

The late 1890s saw the heyday of the Gaiety Girl. The nightworld of the West End, enthusiastically traversed by Shiel, Dowson, and their bohemian cronies, was spangledwith the lights of Leicester Square’s palatial Empire and minareted Alhambra,while the Sacred Flame of Burlesque burned brightly at The Gaiety and Daly’s on the Strand.

Of all the ‘Girl’ shows the longest running was The Geisha (1896) starring Marie Tempest as O Mimosa San, ‘a Japanesey, free and easy, Tea-house girl’. The Geisha took its cue from the japonisme of The Mikado(1885) and its topicality from Japan’s rise, however it was the richer repertoire of chinoiserie spectacle that would hold sway with the London public into the new century, a trend that would continue with Musical Comedy shows such as San Toy (1899), A Chinese Honeymoon (1901), The Blue Moon (1905),The White Chrysanthemum (1905),The New Aladdin (1906), See See (1906),and Chu Chin Chow (1916).

Chinoiserie Musical Comedy invariably revolved around an inter-racial romance, yet modern and daring as the shows may have seemed, these relationships were strictly one-way traffic, gallant English boy falls for sweet Oriental girl. There was no way that ‘a Chinaman’ could be the romantic lead. While it was central to Sino-British relations to maintain sexual barricades between British and Chinese this was suspended on-stage in the interests of Marie Tempest or Lily Elsie looking gorgeous as kimono-clad dolls, part of the willow-pattern scenery that wafted audiences to a far-away world of temple bells and pagodas where the trials and tribulations of love are always happily resolved by the last act.

Turning to The Yellow Danger then, we might find it less preposterous that a pan-Asian mastermind unleashes global war on account of an unrequited passion for an English nursery maid who snubs him on a London omnibus if we recognise that the romantic plot derives directly from the realms of Gaiety Musical Comedy. Ada Seward is the woman who, alone in all the world, had been able to melt the icy heart of Dr. Yen How:

She was a small creature, with skin of a warm yellowish colour, and little quaint Chinese eyes, and light hair with the whitest tinge of red in it; not perhaps pretty, but with some unspeakable attraction of piquancy about her uncommon, saucy little face, which had caused her to receive twelve offers of marriage before she was twenty. Her friends declared that she was the living image of Miss Marie Tempest, the ‘ Geisha ‘ prima donna.

After their paths first cross on Fulham bound bus, Yen How pursues Ada who cannot but find the attentions of ‘a little Chinaman’ risible.

There is no fog in The Yellow Danger, but much drizzle, hackney cabs, buses, and the ‘occasional bicycle’.The hero is a young naval Sub-Lieutenant, John Hardy. Fresh from trouncing the French in the Channel and widely trumpeted as England’s saviour, Hardy is nonetheless downcast because his ‘New Woman’ sweetheart has refused his offer of marriage, being ‘taken up by … a thing which she called ‘Art”. On remembering ‘that one could smoke and drink in music-halls’ Hardy, dashing and noble but when it comes to the pleasures of the flesh, endearingly susceptible, revives. ‘By heaven ! he would make a night of it. …Now then for Bacchus and Terpsichore; wine, and song, and Woman ?’Shiel captures the raucous jingoism of English Music Hall at the turn of the century:

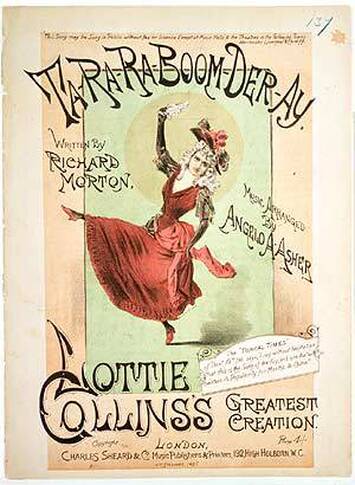

London was alight. The streets thronged with people. The facades of the Palace were arrayed with galaxies of jets. There, on a board, the ink still wet, appeared the attraction of the night: MISS LOTTIE COLLINS Will Appear To-night In Her New Patriotic Song, Entitled : BRAVO, JOHN HARDY!

Entering incognito, Hardy finds himself sitting next to a pretty girl and ‘during a loud song consigning the German nation to perdition’, they begin to flirt:

In a few minutes John Hardy and Ada [for it is she] were talking, Ada laughing, John smiling. Brandy-and-soda became the order of the day. Hardy had soon a good deal more than enough. Miss Collins had bounded on to the stage, bedraperied from head to heel in the Union Jack. The air was electric.

Lottie Collins, then breaks into her real-life signature tune, the famous ‘Ta-ra-ra-Boom-de-aye!’

The tune was simple and stirring the words were like raw rum, as crude and as strong:

When the Allied fleet came over, and passed the Straits of Dover,

They thought they’d have it all their little way ;

But a knowing little cardy (they call him Johnnie Hardy),

He crashed them his Ta-ra-ra-Boom-de-aye.

Collins, a former Gaiety girl, would sing the first verse demurely and then launch into an uninhibited chorus accompanied by energetic can-can kicks on the word ‘BOOM’ that exposed her scarlet stockings and garters.

Collins, a former Gaiety girl, would sing the first verse demurely and then launch into an uninhibited chorus accompanied by energetic can-can kicks on the word ‘BOOM’ that exposed her scarlet stockings and garters.

Once more she repeated the chorus, the audience taking it clamorously up. Then she tripped from the stage. But the house roared after her with the frenzy of men parting with their last earthly hope. She had now utterly mesmerized and enthralled them. The moment was ecstatic with an electrical tension impossible to describe.

The centrality of the figure of the actress and dancer across literature and painting at the turn of the century indicates the intense focus there was on the changing roles of women. While Lottie Collins high-kicked her way through ‘Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay!’ in a Dionysian challenge to Victorian convention that roused more than patriotism in her male audience, a reactionary patriarchy on both sides of the footlights sought to define its own New Woman. The Gaiety Geisha blushing coyly behind her twirling parasol or fluttering fan was as far from the forbidding bluestocking as it was possible to get.

The burgeoning independence of women, actresses and chorus girls, typists and shopgirls worried the eugenicists and Social Purity campaigners who held women responsible for averting the nation’s physical and moral decline. The interdependence of individual moral health with national well-being and racial fitness was seen as crucial to Britain’s defence capabilities and status as a world power. Susceptible flirts like Ada Seward, with her ‘little Chinese eyes’ and ‘piquant Geisha-girl face, warm-yellow in tint’ pose an evident risk to national security. In continually telling and retelling the story of female imperilment, the Yellow Peril narrative taken up by Sax Rohmer would assert that without dependence and surveillance, young women were in deadly danger and so was their country

The Yellow Danger was, during his lifetime, Shiel’s most successful book, going through numerous editions, particularly when the Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901 seemed to confirm his fictional portrayal of Chinese hostility towards the West. The scenario of The Yellow Danger was described as imminent in The Times’ own reporting of a Boxer ‘massacre’ in Peking. Readers were warned to prepare for ‘a universal uprising of the yellow race’ (17 July 1900). Fake news of ‘atrocities’ in the outposts of Britain’s empire and increasingly the notion of a Yellow Peril at its heart stoked a fear and loathing of the Chinese.

Before long, London’s small Chinatown in the Limehouse docks would find itself targeted by the gamut of paranoia. In 1901 though, English xenophobia was directed principally towards the East End’s Jewish immigrants fleeing Russia’s pogroms. This led to the passing of the first British Aliens Act in 1905, aimed at the control of ‘dirty destitute, diseased, verminous and criminal foreigners’ (Manchester Evening Chronicle, 1905) entering the country.

[I] could not believe that I was in England, for all were dark-skinned people, three gaudily-dressed, and two in flowing white robes … never saw I, except in Constantinople where I once lived eighteen months so variegated a mixture of races, black, brunette brown, yellow, white, in all the shades … over-looking them all, one English boy with a clean Eton collar sitting on a bicycle. (M.P. Shiel, The Purple Cloud, 1901)

This paragraph strikes the leitmotif of Shiel’s 1901 serial, The Purple Cloud, a work of titanic eccentricity and weirdness. Its protagonist, Adam Jeffson, the last man left alive, has returned from an Arctic expedition to discover that a purple vapour with an odour of almonds has poisoned the planet causing all to flee before it. Jeffson gets high on opium and in an ecstasy of pyromania watches London burn from the vantage of Hampstead Heath. The deathly purple cloud of Shiel’s novel renders the foreign ‘invasion’ of England a purely aesthetic one,a vehicle for the fierce sybaritic mania of his protagonist.

The Purple Cloud is exemplary fin-de-siècle gothic. With extraordinary aesthetic panache Shiel mixed up evolutionary science and modern technologies with occult pseudo-sciences such as theosophy and mesmerism and geological speculation,thanks to which miasmic atmosphericsprovide monstrous metaphor for foreign incursion. In The Yellow Danger a volcanic eruption presages the encroaching Chinese:

The Purple Cloud is exemplary fin-de-siècle gothic. With extraordinary aesthetic panache Shiel mixed up evolutionary science and modern technologies with occult pseudo-sciences such as theosophy and mesmerism and geological speculation,thanks to which miasmic atmosphericsprovide monstrous metaphor for foreign incursion. In The Yellow Danger a volcanic eruption presages the encroaching Chinese:

Towards noon, during all the week, the sun was not wholly hidden, but appeared as a garish blotch of leprous lavender, giving nothing that could be called light, making only the darkness visible; while, as if to vie in chromatic hideousness, the moon appeared one night for an hour as a black eye-socket, with a rim of pallid green; and then disappeared.

An overlooked and enduring legacy of Shiel’s was that London’s Chinatown would always and forever be wreathed in evil-smelling river mists and creeping yellow fog.

London was fog-bound … The dull reports of fog-signals had become a part of the metropolitan bombilation, but hitherto the choking mist had not secured a strangle-hold.

Now, however, it had triumphed, casting its thick net over the city as if eager to stifle the pulsing life of the new Babylon. In the neighborhood of the Docks its density was extraordinary, and the purlieus of Limehouse became mere mysterious gullies of smoke impossible to navigate unless one were very familiar with their intricacies and dangers. (Sax Rohmer, Dope: A Story of Chinatown and the Drug Traffic 1918)

By the time Sax Rohmer published Yellow Shadows in 1925, the fact that Chinese Limehouse was permanently enshrouded in yellow fog had been established chiefly by him, in seven novels of London’s Yellow Peril, (only three of which in fact featured Dr Fu Manchu).

In the opening chapter of Yellow Shadows the last train from Blackwall to Fenchurch Street is ‘yellowly’ held up by ‘a most formidable bank of fog on the very borders of Chinatown’ thereby allowing ‘gruesome drama’ to intrude upon the life of aspiring playwright, Bernard Hope. He is startled by the sudden phantom-like appearance in his compartment of an elegant but dishevelled ‘slant-eyed’ woman. Suzee Che Lo is a beauty according to the lights of a Futurist artist, ‘a type too unusual to appeal to every man’. Hope’s intended, Yvette Chalmers, on the other hand affords a ‘very charming study for an artist not obsessed by the modern cult of ugliness’. Yvette is an actress on the West End stage. While Yvette is made of more stalwart stuff than her forerunner, Rita Dresden, the fragile, drug-addicted protagonist of Dope, both live the kind of rackety, Bohemian lives that render a girl vulnerable to Chinese wiles.

In the opening chapter of Yellow Shadows the last train from Blackwall to Fenchurch Street is ‘yellowly’ held up by ‘a most formidable bank of fog on the very borders of Chinatown’ thereby allowing ‘gruesome drama’ to intrude upon the life of aspiring playwright, Bernard Hope. He is startled by the sudden phantom-like appearance in his compartment of an elegant but dishevelled ‘slant-eyed’ woman. Suzee Che Lo is a beauty according to the lights of a Futurist artist, ‘a type too unusual to appeal to every man’. Hope’s intended, Yvette Chalmers, on the other hand affords a ‘very charming study for an artist not obsessed by the modern cult of ugliness’. Yvette is an actress on the West End stage. While Yvette is made of more stalwart stuff than her forerunner, Rita Dresden, the fragile, drug-addicted protagonist of Dope, both live the kind of rackety, Bohemian lives that render a girl vulnerable to Chinese wiles.

Rohmer based Dope on the case of Billie Carleton, a Musical Comedy starlet who famously was found dead in her Savoy suiteafter the Armistice night Victory Ball at the Albert Hall having overdosedon cocaine supplied by a Limehouse Chinese. An equally high-profile fatality would be the catalyst for Yellow Shadows. This time a young nightclub hostess, Freda Kempton, was found dead in her Paddington flat from cocaine poisoning. A Chinese restaurateur, known in the West End as Brilliant Chang, was arraigned. The newspapers were not slow in drawing damning links between the dapper Chang who appeared to have a finger in many pies and the fictitious Fu Manchu. Rohmer would complete the pernicious circuit of life and art barely disguising Brilliant Chang as Burma Chang, ‘the richest man in Chinatown’ and evil genius of Yellow Shadows.

As the aesthetic ferment of the 1890s settled into modernist divide, the forces of reaction found an influential mouthpiece in Sax Rohmer’s mass-market fiction which pandered blatantly to public suspicion of futurist ‘abnormalities in art, music and literature’. Among the West’s pantheon of mutable icons, the mummies, zombies and vampires whose popular persistence testifies to fin-de-siècle anxieties then and now, must be counted the sickly vapours and perilous hues of the Yellow Danger. Bohemian susceptibility to intoxicating or hallucinogenic substances, poisonous perfumes and hypnotic incense, gave way in later decades to the invisible chemical substances, odourless fluids, essences, and germs of the Cold War period. Most recently the permeable interface of the West’s communications infrastructure is deemed at risk from intangible Chinese cyber attack as the technological infiltration of our virtual cracks render us as vulnerable as ever to the fictional threat of Chinese world domination.

As the aesthetic ferment of the 1890s settled into modernist divide, the forces of reaction found an influential mouthpiece in Sax Rohmer’s mass-market fiction which pandered blatantly to public suspicion of futurist ‘abnormalities in art, music and literature’. Among the West’s pantheon of mutable icons, the mummies, zombies and vampires whose popular persistence testifies to fin-de-siècle anxieties then and now, must be counted the sickly vapours and perilous hues of the Yellow Danger. Bohemian susceptibility to intoxicating or hallucinogenic substances, poisonous perfumes and hypnotic incense, gave way in later decades to the invisible chemical substances, odourless fluids, essences, and germs of the Cold War period. Most recently the permeable interface of the West’s communications infrastructure is deemed at risk from intangible Chinese cyber attack as the technological infiltration of our virtual cracks render us as vulnerable as ever to the fictional threat of Chinese world domination.

Dr Anne Witchard is Reader in English Literature and Cultural Studies at the University of Westminster. She has published widely on the Gothic, Chinoiserie and Orientalism. She has also written for the London Fictions website about Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights and Lao She’s Mr Ma and Son.

Further Reading

Phil Baker and Antony Clayton (eds), Lord of Strange Deaths: the fiendish world of Sax Rohmer (London, Strange Attractor Press, 2017)

Harold Billings, M.P. Shiel: a biography of his early years (Austin, Roger Beacham Publisher, 2005)

Marek Kohn, Dope Girls: The Birth of the British Drug Underground (London: Granta, 2003)

Sax Rohmer, Dope: A Story of Chinatown and the Drug Traffic, 1918

Sax Rohmer, Yellow Shadows, 1925

All rights to the text remain with the author.