Andrew Whitehead

‘It is very much my first London book’, Kamila Shamsie has said of Home Fire, published in 2017, ten years after its author had made London her home. It is a global novel, set in part in Amherst on the US East Coast, in Istanbul, in Raqqa when it was under Islamic State’s control, and in the city where Kamila Shamsie grew up, Karachi.

‘London’s been a through line in my life,’ she told the Evening Standard. ‘It was where we would come on summer holidays and there’s a part of me that is still that 15-year-old girl arriving excitedly from Karachi. I love that the whole world is here. And that largely it is a city where people recognise that as a strength. And that … with all the horrors that have been happening, London voted in a Muslim Mayor who had had this extraordinarily bigoted campaign run against him.’

Home Fire is concerned above all about issues of identity, loyalty, grief, belonging. The central event is the recruitment of a nineteen-year-old Londoner of Pakistani descent to Islamic radicalism. He is emulating the father he never knew, a jihadi who died while in transit from the notorious Bagram air base outside Kabul to Guantanamo. Parvaiz Pasha heads to Syria leaving behind: a twin sister, Aneeka, a law student and devout Muslim … an older sister, Isma, who has acted as parent since their mother’s sudden death … and Aunty Naseem who provides a home to the twins when Isma heads off to pursue her dream of a PhD from an American University.

The other family whose fate is entwined with the Pashas is that of Karamat Lone, also of Pakistani descent, who has become a hardline Home Secretary in a right-wing British government. As an MP he had refused to enquire into the fate of Parvaiz’s father, Abu Parvaiz. Karamat’s wife, Terry, is Irish-American. Their privileged son, Eamonn, meets Isma at Amherst, and when back in London, while delivering a package from Isma, comes across her younger sister Aneeka and they become lovers.

It’s a gripping story – told with style and energy, and while not a thriller in the conventional sense, it has something of that feel. It’s also a reimagining of one of the masterpieces of classical Greek drama, Sophocles’ Antigone – a tragedy of course, so it’s hardly a spoiler to say that things don’t end well.

Home Fire is also about issues which touch on the author’s own life: nationality, and all the issues bound up with that (Shamsie has become a British citizen, in part because she didn’t want to risk being slung out of a country which is becoming increasingly insular) … and being a Muslim at a time of Islamophobia. ‘It’s my seventh novel, there are Muslims in all of them and Isma’s my first head-covering one’, she said an an interview to the Evening Standard. ‘In some ways, this book became a way of exploring my own complicated relationship to the hijab. No one in my family has worn any kind of head covering in four generations.’

All the central characters are from families which have (or had) roots in Pakistan – and are wrestling with sometimes conflicting loyalties to community, faith and nation. ‘I don’t know that race identity is particularly critical to me, actually. I would say structural imbalances of power interest me; sometimes that takes the form of sexism, sometimes racism, sometimes other forms of discrimination’, Shamsie told the Bookwitty website. ‘Compared to the last couple of books this one felt quite “research lite”—a lot of the contemporary politics was already in my head, and much of the book was set in Massachusetts and London, both places I’ve lived in and know. Though I did do some wandering through the Preston Road neighbourhood of London and spoke to people there to help me create the Pasha family. The section that involved the most research was life in Raqqa under the Islamic State, for which I relied on documentaries, news reports, interviews, illustrations etc that I found online.’

That research on Raqqa is put to good effect. The novel’s account of life under IS is gripping. Parvaiz is an audio geek and ends up in the IS media unit – in a nice villa, with the use of a 4×4 car and the early prospect of a bride allotted by the marriage bureau. So it’s a soft landing, until he’s required to help film an execution and told not to help a London girl trapped after an American bombing raid because she’s not wearing a veil.

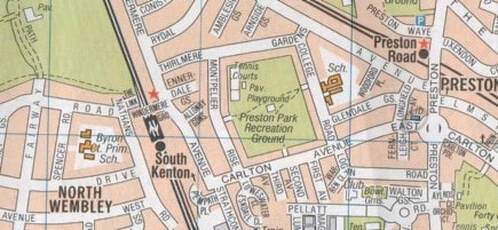

London, though, is the novel’s primary setting: Karamat Lone lives in Holland Park; his son Eamonn has the use of a capacious family-owned flat in Notting Hill; but it’s the Preston Road district of Wembley where the Pasha family lives which is described with most care. Shamsie acknowledges the help of Geraldine Cooke – ‘friend, guide, fact checker’, who runs a small literary agency in Wembley Park – in introducing her to the area and its residents.

A stroll round Preston Road – a stop on the Metropolitan line though hardly Betjeman’s MetroLand – reveals an area neither poor nor prosperous, diverse but perhaps less preponderantly South Asian than adjoining areas of Wembley and Harrow.

Eamonn is the character who walks London most restlessly. He too has roots, though tenuous, in Preston Road – it was where he would go on Muslim holy days in the period before his father rejected Islam as a barrier towards integration. On one occasion, Eamonn walks ‘north towards Preston Road, where everything turned residential, suburban. Any one of these semi-detached houses could be the home in which he’d spent all those Eid afternoons …’.

The Pasha family home is sufficiently close to Preston Road tube for Parvaiz to sit on top of the garden shed recording the sound of trains entering and leaving the station (at this stage on its journey into the suburbs, the Metropolitan Line runs overground). He helps out at a local greengrocers; Isma has sustained the family by working as the manager at a dry cleaners. Yet the sense of place is not intense; the neighbourhood is not a pervasive presence.

There is one local incident which is reflected in the novel – the campaign to save the local library. This pops up repeatedly. It is the only cause that Parvaiz has shown any interest in, giving money to the campaign as part of his religious obligation to support charity, before he is targetted so effectively by the IS recruiters.

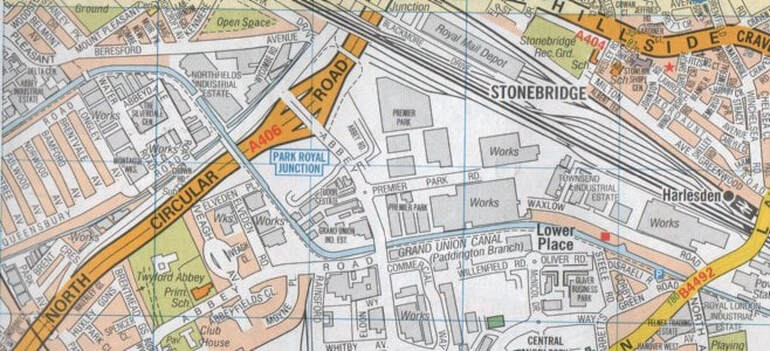

Another aspect of London features more insistently in the novel, though it is incidental to its plot. This is the the Grand Union canal at Alperton, not too far from Preston Road. When in Amherst, Isma looks back on one of the pleasures of her teenage years:

‘She came from a city veined with canals: that had been the revelation of her adolescence … In Alperton, two miles from her old home, she could descend into waterside avenues of calm, unpeopled in comparison to the streets thick with noise through which she’d travelled to arrive there. She knew her mother and grandmother would say it was dangerous, a lone girl walking past industrial estates with no company other than the foliage … so she never said anything more specific than “I’m going for a walk”, which they found both amusing and unthreatening.’

Eamonn also treads this same towpath, coming across the place on this stretch of the Grand Union where it crosses over (yes, over) the North Circular, one of London’s busiest roads , and then Googling ‘canal above North Circular’ to learn of the 1939 IRA bomb attack on this outsize aqueduct which failed to bring millions of gallons of water in torrents down on to these outer reaches of North London. He takes this route on the most fateful of journeys in the novel – when he walks along the canal to deliver a package from Isma, and so meets her sister Aneeka for the first time (though it’s hard to make out how this would have been on his route). He talks about the canal crossing the road and the IRA attack, prompting his introduction to ‘GWM’ … the offence of Googling While Muslim.

And if you don’t believe that a canal can run over a main road – take a look.

All rights to the text remain with the author.