Suneel Mehmi

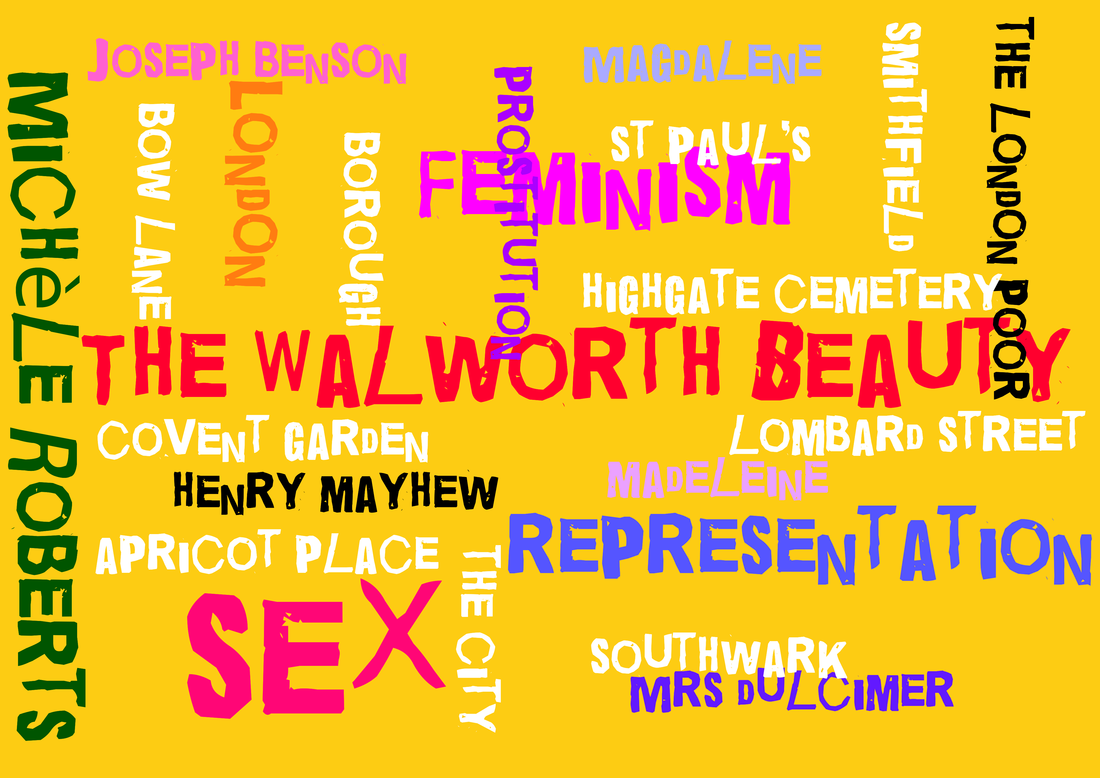

Michèle Roberts was raised in and lives in London. She was brought up in Edgware and she currently resides in South-East London. The city itself has been seen as being a key creative influence on her writing. In 2008, Dr Jules Smith observed that Roberts’s ‘exploration of London, the various areas and houses that she lived in, went alongside her development as a writer’. The Walworth Beauty shows a fascination with the city and the exploration of its spaces and people both in the present and across historical time.

The novel oscillates between two settings which interact with each other and have considerable overlaps. One is a Victorian London underworld of prostitutes and ‘fallen women’ represented by the experiences of Joseph Benson when he comes into contact with a black Londoner called Mrs Dulcimer. The other setting is more familiar. It is that of the contemporary scene in which Madeleine’s experiences tell the story of London and Londoners.

As can be seen from the title, in which a woman is named after an area in London, one of the key concerns of the novel is the representation of London life and Londoners, especially female Londoners. The novel emphasises the point since Joseph Benson is imagined as a researcher into the living conditions of prostitutes for London Labour and the London Poor, a work of Victorian journalism by Henry Mayhew which was written between the 1840s and the 1850s.

Mayhew’s towering work is often cited as breathing life into the experiences of London’s poor, as a rich repository of fact. However, Joseph finds that his researches into the lives of prostitutes and ‘fallen women’, and his sympathy, cannot be corseted into the unemotional and statistic-heavy writing that Mayhew wishes to compose. This representation, he finds, is horribly inadequate and inhumane. Joseph also sees this form of representation to be rooted in a conservative and masculine Victorian mindset which is ignorant of women and their lives. Joseph ‘rewrites’ the representation of London prostitutes in the novel, or reimagines them. Similarly, Arina Cirstea has called some of Roberts’s works a ‘re-writing of London’.

The novel itself can be seen to mirror Joseph’s assessment and ‘rewriting’ of Mayhew’s representation of London and London women since it eschews figures, facts and distance in favour of exploring the character of ‘fallen women’ and the concrete reality of their day-to-day lives and choices. The novel appears to champion its form as an empathetic and emotional woman’s perspective over the abstract and scientific perspective of a man like Mayhew who doesn’t even conduct his own research and interviews and doesn’t appear to have any real experience of how marginalised groups live their lives.

The Walworth Beauty aims to show that Mayhew’s abstract notions of the representation of city life and its people are firmly situated in Victorian times, a time when white, middle class men held the reins of power and their perspective dominated intellectual and cultural life. The novel suggests that it has moved away from this perspective because the reader can see that it mirrors the writing of Mrs Dulcimer, the black woman in the novel. Roberts’s novel is a ghost story and we know that Mrs Dulcimer also writes ghost stories. The novel therefore aligns itself with the voice of the difference. It is not written from the place of the masculine and white elite but from the place of the black, ethnic minority woman.

One of the many ways in which Roberts aims to distinguish her representation of London and Londoners from Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor and the Victorian mind is by representing the city not as some sort of unmoving monolith or static object, but as an entity in the process of constant change. The novel actually begins by describing this process of change that gives London its character and fluidity. The major setting of the novel, Apricot Place, is shown as a newly ‘Londonised’ area which was once a town. We later find that Joseph has an out of date map of the area, even though the map is only a few years old.

Roberts is writing of a city that is in a process of continual transformation: her fictional map of the city is one which registers continual historical movement. The structure of the novel reflects this. The two oscillating time periods which communicate with each other in the voices of past and present have been caught by Roberts. Characters in the novel know that they are framed in terms of differing historical realities. Hence, Madeleine states that, “I’m in the present and the past both at the same time, one delicately folded around the other.”

There is a startling claim which is implicit in the work. Unlike Mayhew’s study, which the novel suggests is rooted in a political conservatism which resists change and other perspectives, and which is rooted to one historical period, Roberts seems to be claiming that her fictional work is radically transformative and will change perspectives, and through perspective, the past, the present and the future. Roberts aims to demonstrate that her novel can traverse and represent past, present and future and that the experience of women and their fight against patriarchy can provide grounding for the understanding of any historical period.

As is to be expected, the careful theoretical exploration of the city across time is matched by its investigation by the characters in the novel. Thus the itineraries of the characters are described in detail. Madeleine seems to represent both the academic and the physical investigation of the urban terrain. She reads histories of the city and Mayhew’s work and Roberts draws attention to the subversive, feminist being of this observer who is not described as a flâneur, since it is men who are flâneurs, but rather as a ‘flâneuse’. Roberts has written of this female flâneur in her 2007 autobiography Paper Houses:

‘My narrative in one sense goes in a straight line, chronologically, charting my rake’s progress, but in another sense is a flâneur…. The flâneur enjoys being enticed down side streets. She doesn’t particularly want to direct the traffic when she’s out for a wander. She follows her nose. She follows her desire. When you write you’re in charge, in one sense, and not at all in another…. You forget yourself and just get on with writing, just as, walking in the city, you can dissolve into the crowd, simply float, listen, look.’

A minor female character in the novel called Rose is also interested in “street space” and makes models of the city which are integrated with Madeleine’s written memories of her grandmother’s stories about London. Rose represents the future of womanhood as she is a teenage art student and is, literally, the future, with her whole life before her. Roberts is showing that women’s vision of the city is the present and the future. It is a masculine view of the city that is the past.

‘I did this drawing while I was reading the novel.

It shows a woman moving away from the light in the city towards the moon.

Light is a traditional metaphor for truth and knowledge,

and the moon is traditionally associated with femininity’.

As a living woman, Roberts draws heavily on various autobiographical elements to enrich her woman’s perspective of the capital and its people. It is indicative that Madeleine is a university professor like Roberts herself, one who is also concerned with literature and who pursues creative writing. Roberts is also the daughter of a French Catholic mother and an English Protestant father and has dual French-English nationality. This is a formative influence on the novel since it depicts two French-English marriages in Victorian London from the viewpoint of Joseph Benson. As a result, the novel features a host of French characters living, like the French-English Roberts, in London. Madeleine, the contemporary character, has also lived in France for a time, as has the other main character in the novel, the intriguing Mrs Dulcimer.

Drawing from these personal resources has presented Roberts’s novel from falling into a parochial trap since she is able to make the story just as much about London’s immigrants as well as Englishmen. If identity is then the key concern of the novel, and the identity of London and the Londoner, then the personal identity of Roberts is also paramount in understanding the work.

The Walworth Beauty is a rich and sophisticated novel and there are many themes which relate to each other. There is the representation of race, immigration and its cultural meaning through the character of Mrs Dulcimer and others. Roberts also explores the concept of marriage and meaning. There is the representation of homosexuality which forms a contrast to Joseph’s Victorian notions of marriage and masculinity, for example. There are other notable themes such as pornography and how it interacts with fictional depictions of sex, which the novel is full of.

One theme which I found particularly interesting was how the novel positioned itself in relation to Christianity and the Bible. Roberts forces the ideas on the reader because of the names of the major characters and the narrative events which unfold, which I will not explore here because I don’t wish to spoil any surprises for the readers. There is Joseph who is named after the father of Christ. Madeleine is named after Mary Magdalene, the prostitute, as she states. The figure therefore resonates on several levels because of the representation of prostitutes in the novel and Mary Magdalene’s importance as a symbol for the ‘fallen woman’ in Victorian times and the present. The depiction of a minor character also brings in another significant actor. He is called Emmanuel after Jesus Christ.

This novel is one that is difficult to introduce and sum up without going into the narrative in much detail, but in conclusion, Michèle Roberts’s London in The Walworth Beauty is an intriguing and exciting theoretical space of the female and feminist imagination. Her Londoners are equally as interesting and innovative. The novel both represents the City and its inhabitants from a uniquely female perspective and calls past representations into question.

Whether or not the reader supports feminism, or the feminist claims that Roberts is making about truth, knowledge and the Victorians, the novel is a fresh, experimental approach to the representation of London and the people who make it what it is. Roberts has made an important fictional contribution to how we think about London and how we think about thinking about London.

Suneel Mehmi is currently researching the relationship between photography and law in fiction from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1920s. He is a scholar and an amateur writer, poet, singer/songwriter, musician and artist. Suneel lives in East London and holds degrees in Law and English Literature from the London School of Economics, Brunel University and the University of Westminster.

References

Arina Cirstea, ‘A Space of One’s Own: Reading Michèle Roberts’ Urban Imaginary’, Peer English, 9 (2014)

Michèle Roberts, Paper Houses: A Memoir of the 1970s and Beyond, London: Virago, 2007

All rights to the text remain with the author.