Bobby Seal

The idea of the flâneur was born in Paris and was first referred to by Baudelaire. However, London writers have long used the device of the casual wanderer of the capital’s streets, the loiterer, the observer, as a means of exploring London and the inhabitants of her streets. Dickens, Gissing, Morrison all wrote about life on London’s streets through characters who wandered them on foot. Dorothy Miller Richardson, however, was the first writer to create a female central character, Miriam Henderson, who freely walked and explored London’s streets. In doing so, Richardson created the first, and arguably still the best-realised, flâneuse in London literature.

Dorothy Richardson is generally not regarded as a major figure in the canon of English literature. However, for the early part of her career she was seen as a leading female modernist and an equal of Virginia Woolf. But, despite her early success, Richardson’s reputation has sadly not proved to be as enduring as that of Woolf.

Richardson was born in 1873 and brought up in Putney. She enjoyed an apparently conventional middle-class upbringing until her father was declared bankrupt when she was seventeen and she had to leave home to take up work as a governess. While Richardson was still very young her mother began to suffer with increasingly severe bouts of depression which eventually led to her death by suicide in 1895. Richardson moved to Bloomsbury the following year and, while working in a dental surgery by day, she began to write in her spare time and soon started to have short stories, reviews and poems published in a number of periodicals.

Richardson was born in 1873 and brought up in Putney. She enjoyed an apparently conventional middle-class upbringing until her father was declared bankrupt when she was seventeen and she had to leave home to take up work as a governess. While Richardson was still very young her mother began to suffer with increasingly severe bouts of depression which eventually led to her death by suicide in 1895. Richardson moved to Bloomsbury the following year and, while working in a dental surgery by day, she began to write in her spare time and soon started to have short stories, reviews and poems published in a number of periodicals.

Richardson’s major achievement is the sequence of novels known as Pilgrimage. The series is, in every sense of the word, Dorothy Richardson’s life’s work. Through its thirteen volumes she charts the life of a young woman called Miriam Henderson; a protagonist whose life story very much mirrors the course of Richardson’s own. The Tunnel is one of the key works of the series and, in many ways, the most engaging and certainly the most accessible to the modern reader.

Dorothy Richardson spent most of her adult life in London and this is reflected in the setting of the majority of the volumes of Pilgrimage. The title Pilgrimage is a metaphor for a quest and, in setting most of the series in London, Richardson presents the city as a labyrinth waiting to be wandered and explored. Pilgrimage is Miriam’s journey; an intellectual, psychological and spiritual journey in which her outer quest is matched by an inner one.

The Tunnel is the fourth volume in the series and covers the period of Miriam’s arrival in London at the age of 21. Reflecting Richardson’s own life, she takes a room in a house in Bloomsbury and starts work as a receptionist at a dental surgery. In the first three volumes Miriam worked as a live-in governess, but The Tunnel marks her first step towards complete independence. In taking a room of her own, Miriam finally confirms her break from the conformity of the life that was expected of her; that is to live in her father’s home until she married, as would be the case with her sisters. This step out into the world marks her downward mobility from being a gentleman’s daughter to becoming a working woman.

The Tunnel is the fourth volume in the series and covers the period of Miriam’s arrival in London at the age of 21. Reflecting Richardson’s own life, she takes a room in a house in Bloomsbury and starts work as a receptionist at a dental surgery. In the first three volumes Miriam worked as a live-in governess, but The Tunnel marks her first step towards complete independence. In taking a room of her own, Miriam finally confirms her break from the conformity of the life that was expected of her; that is to live in her father’s home until she married, as would be the case with her sisters. This step out into the world marks her downward mobility from being a gentleman’s daughter to becoming a working woman.

But Miriam’s world is not limited to her room in a Bloomsbury lodging house. She attends lectures and plays and becomes interested in literature and politics. Throughout the course of The Tunnel Miriam reads avidly, seemingly looking behind the words of the novels she reads to find submerged meanings. But gradually Miriam begins to focus on the words themselves, almost as if she is switching from looking at the reflection in a mirror to looking at the mirror itself and at its frame. She struggles with the canonical texts of science and literature, rejecting the standard masculine approach but finding it difficult to develop an understanding of a feminist alternative. Pilgrimage represents Miriam’s (and by implication Dorothy Richardson’s) journey to a greater understanding of herself and of female consciousness in general.

The Tunnel opens with Miriam taking a room of her own in Bloomsbury. The room is cramped and dreary, but to Miriam it represents the freedom she longs for:

She closed the door and stood just inside it looking at the room. It was smaller than her memory of it. When she had stood in the middle of the floor with Mrs Bailey, she had looked at nothing but Mrs Bailey, waiting for the moment to ask about the rent. Coming upstairs she had felt the room was hers and barely glanced at it when Mrs Bailey opened the door. From the moment of waiting on the stone steps outside the front door, everything had opened to the movement of her impulse. She was surprised now at her familiarity with the details of the room . . . that idea of visiting places in dreams. It was something more than that . . . all the real part of your life has a real dream in it; some of the real dream part of you coming true.

The focus of The Tunnel constantly moves from Miriam in her room to Miriam in the world outside. Whilst having a room of her own to retreat to gives her the space for personal growth and spiritual reflection, the world outside, and the freedom to roam through it, gives Miriam the opportunity to develop a new social identity. The Tunnel represents a journey for Miriam; digging down through the influences of the past to reach a different, perhaps truer, version of herself that she hopes to achieve at some point in the future. She travels through this ‘tunnel’ with hope of there being light at the end of it; even when the light is not yet discernible. Miriam urges herself forward with the faith of the true pilgrim and with the conviction she will emerge into a place where all is brighter and clearer.

In a key section of The Tunnel, Miriam resumes contact with her old school friend, Alma. Through her she meets Alma’s husband, a writer known as Hypo G Wilson. Wilson is clearly based on HG Wells, with whom, we now know, Richardson had a short-lived affair. In fact, it is suggested that Richardson became pregnant by Wells, though she had a miscarriage before full term.

In essence, Richardson’s London represents the maternal, and The Tunnel marks the development of a feminist critique of the patriarchal world Miriam lives in. It is her break from the lingering influence of her father. When she is away from London she longs to return to the city’s embrace:

No one in the world would oust this mighty lover, always receiving her back without words, engulfing and laving her untouched, liberating and expanding to the whole range of her being. . . She would travel further than the longest journey, swifter than the most rapid flight, down and down into an oblivion deeper than sleep. . . tingling to the spread of London all about her, herself one with it, feeling her life flow outwards, north, south, east and west, to all its margins.

Up until this point the notion of a psychological journey, a pilgrimage, had been seen by writers in entirely male terms. The development of psychological theories and the increased freedom for women to wander through the modern city fed into the fiction of Richardson, and indeed that of Virginia Woolf.

Miriam’s new work is hard, the hours long and the pay is just a pound a week but, again, it represents freedom for her, and the chance to establish an independent life free of the influences of her background. The journeys to and from work, sometimes by omnibus and at other times on foot, quickly become the highlight of Miriam’s day. She drinks in the ever-changing sights and sounds of the city and absorbs them into her being:

Strolling home towards midnight along the narrow pavement of Endsleigh Gardens, Miriam felt as fresh and untroubled as if it were early morning. When she got out of her Hammersmith omnibus into the Tottenham Court Road, she had found that the street had lost its first terrifying impression and had become part of her home.

On one of Miriam’s many walks through the West End she encounters several old men wandering about, slowly and alone, like superannuated flâneurs, ‘still circulating, like the well preserved coins of a past reign.’ She reaches Piccadilly Circus and stops to enjoy its ‘central freedom’, but moves on when she spots Tommy Babington, a former acquaintance. Babington is strolling along with an expressionless face and the dandified clothes of a flâneur. They exchange a momentary glance of recognition:

She rushed on, passing him with a swift salute, saw him raise his hat with mechanical promptitude as she stepped from the kerb and forward, pausing an instant for a passing hansom.

Miriam does not wish to engage with Tommy. She does not want his attention, or his protection; she wishes to enjoy walking alone on the same terms as him, or any other male flâneur. And perhaps it is not coincidental that Richardson has them meet at Piccadilly Circus. Piccadilly is not a crossroads but a roundabout, a place where one encounters and re-encounters other people, as well as aspects of one’s own self; and at the very centre of this place is Eros. Miriam continues her walk; expressing a preference to walk the ‘winding lane’ of Bond Street rather than endure the ‘two monstrous streams’ of traffic on Oxford Street, the former perhaps being more conducive to quiet reflection.

Later that same evening, Miriam encounters a grotesque and dishevelled old woman shambling along in the gutter in Cambridge Square. They steal a glance at each other and Miriam experiences an odd, chilling moment of recognition ‘it was herself, set in her path and waiting through all the years.’ This is one of several instances where Miriam stares into a face she seems to recognise and which suggests an inner searching for alternative possibilities on her journey of self-discovery; a glimpse of the self she was, the one she will become, and the other possibilities that may never come about.

Miriam’s struggle to establish an independent life for herself frequently requires her to cross boundaries of gender and class. Richardson’s descriptions of Miriam’s walks through London in The Tunnel constantly involve her in crossing roads, bridges and railway lines, as if to mirror her crossing of boundaries in her inner pilgrimage. Yet she finds the solitude of the street strangely soothing and less challenging than the other encounters in her life: ‘She went out into its shelter’.

Richardson’s Miriam Henderson wanders through London’s streets both physically and imaginatively. Her propensity to walk the streets alone marks her out as an outsider. She finds herself attracted to the company of other outsider characters. Two Russian Jews whom she meets in Bloomsbury, Mr Mendizabel and Michael Shatov, play an important part in her development. She finds herself attracted to their otherness and finds she shares with them an enjoyment of wandering the city’s streets, particularly at night.

But not all parts of fin de siècle London are places women could safely or comfortably visit. For women such as Miriam, greater freedom in some ways brought with it greater isolation as she found the spaces of the city open to her to be selective, limited, and fragmented from one another. Female earnings were still very low and working women not supported by their family, even educated ones, could only afford the most basic of accommodation. Both the street and her own room were important to the female writer in early twentieth-century London; the one for exploration and the other for reflection. Miriam found both of these in Bloomsbury with its myriad rooms to let and boarding houses.

As if to reflect the ever-changing nature of the modern city, The Tunnel is written in a style that is very different from anything written before. Richardson’s contemporary, May Sinclair, described it as a ‘stream of consciousness’ novel, a term which Richardson never fully accepted. She was dissatisfied with the form of both the romantic and the realist novel. She wanted to write a novel based on her own life experiences, but to transmute it into something different by seeing it through the eyes of her protagonist, Miriam.

Miriam’s voice was to replace Richardson’s. But clearly, there was still a narrator behind that voice. Richardson’s great achievement was to develop a new way of expressing her responses to the world that she saw about her. She was a modernist and a feminist. The Pilgrimage series has been described as the first full-scale impressionist work.

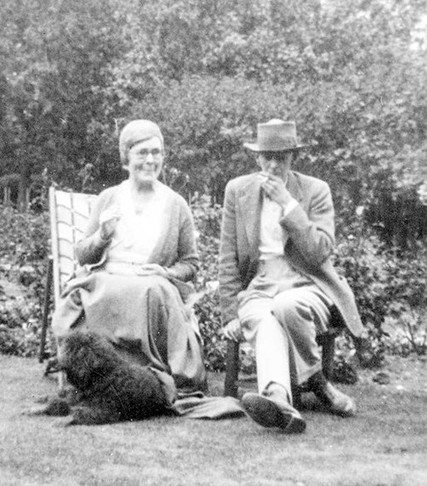

By the time The Tunnel was published in 1919, the early interest in Richardson’s writing had begun to wane. Though she ploughed on with nine further volumes of Pilgrimage, these sold few copies and she had to earn her living as a writer through journalism and reviews. Indeed, Richardson enjoyed a moderately successful second career as a film reviewer. She married the artist, Alan Odle, in 1917 and continued to write up until her death in 1957.

Female modernist writers like Dorothy Richardson, were until recently, largely ignored by the predominantly male establishment of literary criticism. It was not until the 1970s, and the growth of feminist criticism, that writers such as Richardson were given their due credit.

Pilgrimage as a whole is the story of Miriam Henderson’s inner journey, her psychological, political and spiritual development. The Tunnel is a key work in this series in that it charts Miriam’s new, independent life in London. And it is London that is at the core of Richardson’s work.

Bobby Seal is a freelance writer who indulges his fascination with London, literature and psychogeography at his blog: http://psychogeographicreview.com/

Dorothy Richardson’s Bloomsbury

Dorothy Richardson lived for several years in a small attic flat at the top of 7 Endsleigh Street. At this time many of the large Georgian houses in Bloomsbury were divided up for multiple occupation and provided cheap rented rooms for ‘respectable’ working men and women. Richardson’s diary records her paying a rent of £1.00 a week.

Nowadays the whole block, as with many others in the vicinity, belongs to the London School of Economics and is used for student accommodation. As is evident from the picture, the stuccoed ground floor has been restored so that it is no longer the crumbling façade we read of in The Tunnel.

It is difficult to define the exact boundaries of Bloomsbury, but is generally regarded as the area between Euston and Holborn. It is a neighbourhood of large Georgian houses and a number of elegant squares. Many of the larger houses are now used by the University of London and its offshoots and by several medical associations.

Bloomsbury, for much of the twentieth century, was an area favoured by writers and artists. Richardson frequently attended literary soirées at the home of Virginia Woolf in nearby Gordon Square and later, together with other members of the Bloomsbury Group, at other Woolf homes in Fitzroy Square and Brunswick Square. Most of the buildings in Gordon Square now belong to the University of London and the university are currently planning to refurbish the central gardens of the square.

Within walking distance of Bloomsbury, at least for a struggling writer with no money to spend on public transport, was Wimpole Street where Richardson worked as a dental receptionist for many years. The dental practice no longer exists, but the street still has associations with medicine and the British Dental Association is housed at number sixty four. The Royal Society of Medicine, an educational charity, is located at number one.

References and Further Reading

Backwater, 1916

Honeycomb, 1917

The Tunnel, 1919

Interim, 1920

Deadlock, 1921

Revolving Lights, 1923

The Trap, 1925

Oberland, 1927

Dawn’s Left Hand, 1931

Clear Horizon, 1935

Dimple Hill, 1938

March Moonlight, 1967

Horace Gregory, Dorothy Richardson: An Adventure in Self-Discovery (New York, Chicago and San Francisco, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967)

Gillian E Hanscombe, The Art of Life: Dorothy Richardson and the Development of Feminist Consciousness (London and Boston, Peter Owen, 1982)

Deborah Parsons, Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City and Modernity (Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 2000)

Jean Radford (Key Women Writers Series), Dorothy Richardson (Hemel Hempstead, Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1991)

John Rosenberg, Dorothy Richardson: The Genius They Forgot (London, Duckworth, 1973)