Suneel Mehmi

The Watchmaker of Filigree Street is Natasha Pulley’s debut novel. It is a difficult novel to introduce to the reader without giving away the twists and turns of the tale. However, I do feel it is well worth the effort. The novel is set in Victorian London and shares elements with the Steampunk genre, since it features fantastical clockwork, fictional science and a female scientist. The Steampunk genre interacts with the conventions of the detective novel. There are also postmodernist features, since characters in the novel reflect on their own historical context.

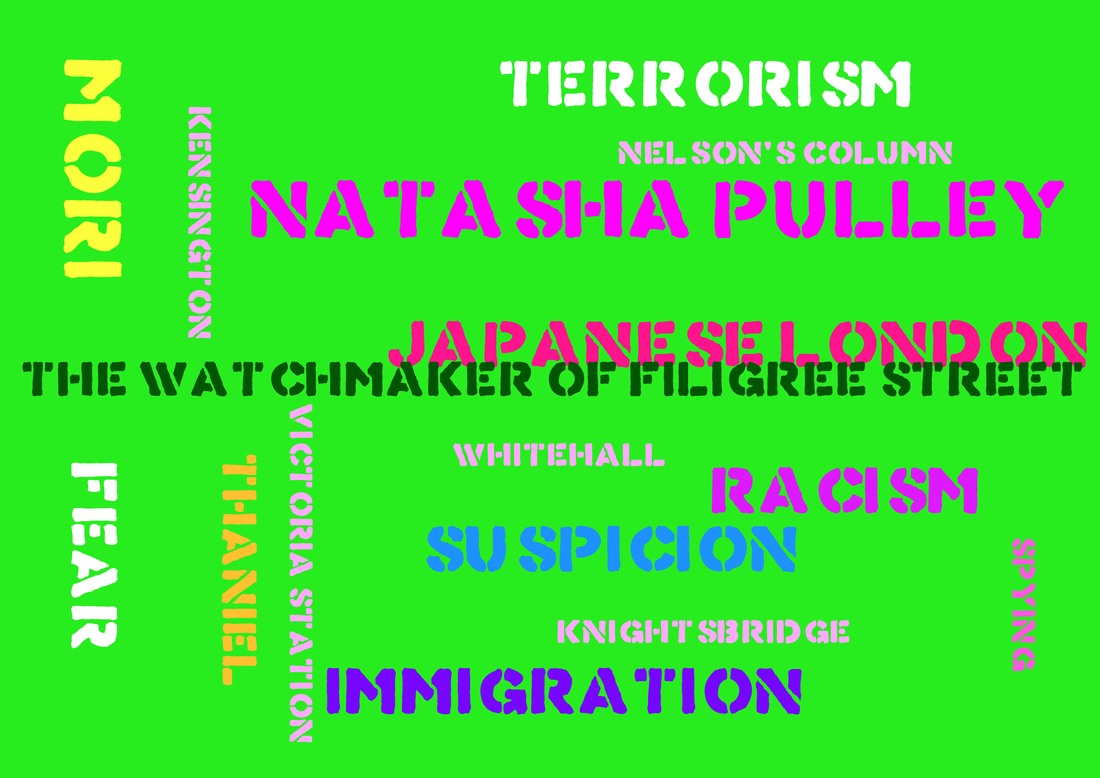

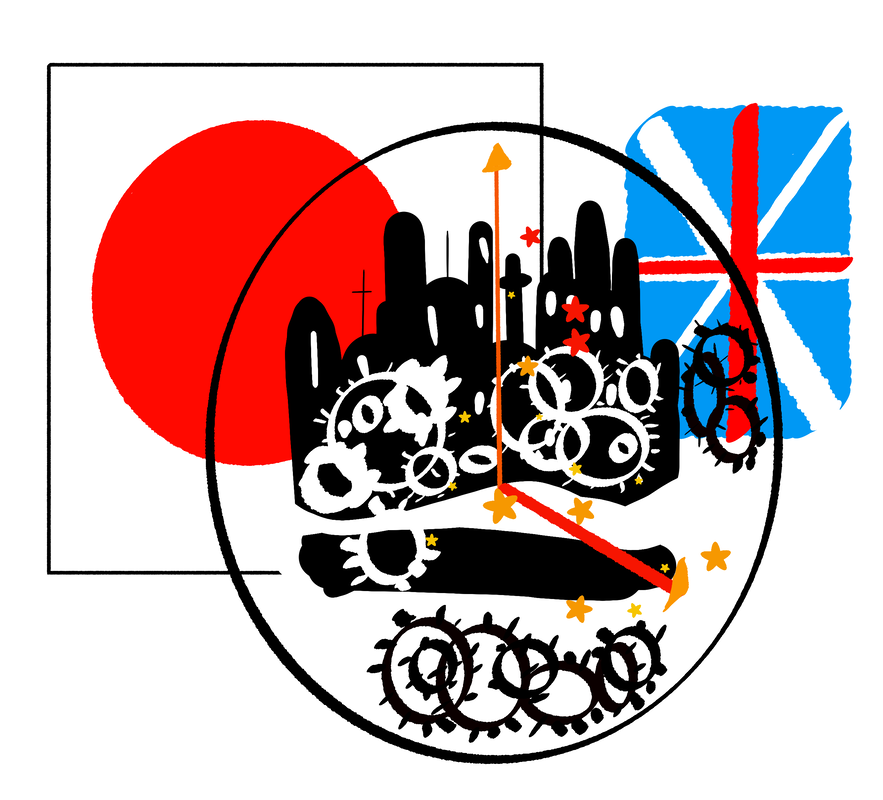

The novel is particularly interesting since it concentrates on Japanese London, a very particular London which hasn’t often come to the attention of the general reader. Japanese London is explored through the portrayal of a Knightsbridge show village, where Japanese life was performed for the English, through depictions of a Japanese tea house in London as well as the residence of the watchmaker of Filigree Street, Mori.

As Pulley writes in the acknowledgements, there is a level of “historical accuracy” to the depiction of Victorian and Japanese London:

With regard to historical accuracy – there is some, mainly courtesy of Lee Jackson’s Dictionary of Victorian London, which includes brilliant resources on the early days of the London Underground, the Knightsbridge show village, the bombing of Scotland Yard and a thousand thousand other interesting things. Natsume Soskeki’s sad and hilarious Tower of London provides a very good idea of what a Japanese man thought of England in the early 1900s.

Although the novel is presented as historical fiction, it is very contemporary because it explores how the London bombings and terrorists affect life and identity in the capital. The novel begins in the political centre of London, the Home Office in Whitehall. There is a threat from Fenian groups to bomb public buildings.

The main character, Thaniel Steepleton is introduced in the midst of the panic. He is working in London as a clerk to support his widowed sister and her children. Thaniel has given up on his dreams like many other Londoners to make ends meet. He barely manages to exist, given his low pay. He had once dreamed of being a pianist.

Victoria station is destroyed. A bomb is defused at Nelson’s Column. Then, Thaniel almost dies in a London bombing. The threat of extinction from a terrorist bomb draws Thaniel into the world of suspicion, espionage and detection that we well know, given the recent London bombings. A watch that seems connected in some way with the bombing leads him to the watchmaker of Filigree Street, the Japanese Mori.

Thaniel, spy, detective, counter-terrorist officer, then becomes introduced to Mori and Victorian Japanese London, and through him, the reader is also introduced to this forgotten world. Filigree Street, in many ways, represents how the current media has represented terrorists. It is described as a “medieval” place, for example. It is also seen as being not quite London. However, this place slowly becomes Thaniel’s home as he learns more about the immigrants in London that are associated, in the public’s mind, with terrorist activities. However, throughout, right until the bitter end, the novel keeps the question alive as to whether Mori, the immigrant, the terrorist suspect, is innocent or guilty.

Because the novel keeps the question hanging, we are given a complete fictional treatment of London’s reaction to terrorist activity. There is both the criticism of the bombings and the praising of them by some groups. The novel presents the latent racism and hostility before the bombings and also the ensuing racism from both sides, for example, from the English and the immigrants. Japanese people can refer casually to all English as ugly in the same way that the English are suspicious of the Japanese in their midst.

The novel shows how much London bombing determines events and futures in the capital. It is a philosophical exploration of how history is determined by terrorism in London. The novel explores in detail how immigration and immigrants are related to terrorist activity and could be seen as an analysis on the matter. There is a key question, a key suspicion, at the heart of the novel which is only answered in its resolution – why has Mori the watchmaker, the immigrant, come to London? Why has he adopted London? Is it for good or for bad? Does he stand for the honest and the good immigrant or for the duplicitous and bad immigrant? How much does he reflect London’s immigrants in actuality? In fact, Mori keeps an ambiguous clockwork model of London in Filigree Street. It shows a city that becomes new. But is this newness something to be supported or denounced?

Because the novel explores suspicion of immigrants on the basis of fears of terrorism and the destruction of London and the Londoner, it can be seen as a valuable historical document of London’s fears at this present moment in history. It is a well thought out exploration of racism in our time. By watching how Thaniel develops by adopting suspicion and taking on the identity of spy, by watching him survive the London bombing, we see how the London individual has been formed into something by terrorist attacks. The question remains whether we see Thaniel as a hero or a villain, a dupe or someone with an authentic identity of his own at the end of the novel. Has Thaniel become stronger after his tryst with extinction in the capital, or has he become weaker? What exactly does it mean to be a resilient Londoner?

Besides its obviously political dimensions, the novel is also an exploration of solitary life in London. It studies loneliness and isolation in the capital. Both Thaniel and Mori are solitary individuals that are brought together by terrorist activity. However, what is the exact basis of their relationship? The reader is kept in suspense and indecision. To find out, one has to come to the end of the novel.

In summary, Pulley’s novel is both history and an analysis of current events. It explores London identities and London’s direction as it has been formed after the recent bombings. To say anything more would be to give away what happens in the ending. And perhaps it is better not to conclusively declare that the novel goes one way or the other. If suspicion of the immigrant and isolation is structural to the novel, then that reflects our contemporary life and one must ask why. If spying is also structural, this prompts further questions. The reader will find it rewarding to analyse this piece of work and try and understand it and the points that it is making. It is a stimulating and thought-provoking read.

Suneel Mehmi is currently researching the relationship between photography and law in fiction from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1920s. He is a scholar and an amateur writer, poet, singer/songwriter, musician and artist. Suneel lives in East London and holds degrees in Law and English Literature from the London School of Economics, Brunel University and the University of Westminster.

All rights to the text remain with the author.