Zoë Fairbairns

A substantially revised version of this article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

This is the introduction to a new edition of This Bed Thy Centre.

It’s posted here by kind permission of Zoë Fairbairns and of the publisher, Five Leaves.

This Bed Thy Centre is a novel about sex. Set in a south London suburb – down-at-heel, but up-and-coming – in the 1930s, it is a reminder of why a permissive society, whatever its drawbacks, is better than the other kind.

Elsie Cotton inhabits the other kind. Sixteen years old and still at school, she wants someone to explain to her about sexual intercourse. Her widowed mother, for whom the discovery that her daughter is growing up is a “new and terrible thought”, is not the ideal person to ask. Neither is Elsie’s secretly-lesbian art teacher, who assures Elsie that “there’s plenty of time for you to worry about that sort of thing.”

Elsie’s boyfriend Roly would be only too happy to give a practical demonstration, if Elsie were not so scared of the unknown, not to mention the all-too-known risks. Marie Stopes’ Married Love has been out since 1918, but if anyone in Elsie’s circle has read it, they’re not telling Elsie.

One person who probably has read it is the cheerfully sexy Patty Maginnis (“the best unpaid whore in town” according to her blabbermouth boyfriends), but she’s got other things on her mind – she fancies Roly herself, and she’s just found a lump in her breast. So Elsie is on her own: needy, anxious, eager and uninformed.

The area is identified only as the Neighbourhood – a suburb where the working poor push barrows, pull pints or work shifts in the candle factory, while the unemployed go job-hunting and the idle rich sleep late before attending the afternoon showing at the cinema and wondering what to have for tea. Those in between struggle to keep up appearances, making a special trip up to Town to buy a new autumn coat (with a not-quite-crêpe-de-chine lining and “two whole foxes” in the collar) before coming home to their terraced houses with cramped bathrooms and pomegranate-motif wallpapers.

The outside world barely intrudes. If news comes on the wireless, the channel is quickly switched to a foreign station, and dance music. The Neighbourhood doesn’t know that another world war is pending, and doesn‘t want to know – apart, perhaps, from Mr Teep, who sits in the pub night after night muttering “Blow ’em all dead” without ever specifying whom he has in mind.

The Neighbourhood has a Woolworth’s, a draper’s, a hairdresser’s offering “Perms from One Guinea”, and a set of traffic lights which, recently installed, are an innovation and a talking-point: passers-by discuss which of the colours they like best. There’s a Library, with a capital L and a no-better-than-she-ought-to-be librarian, and cafes where you can enjoy “a hearty meal of kidneys on toast”. There is also a pre-National Health “panel” of publicly-funded doctors, whose reputations strike such terror into some of their potential patients that illness and even death seem preferable to consulting them. Out on the Common, hot gospellers with bands and hymn-books compete for public attention with the communist orator and the man selling corn plasters.

Never very far away are Elsie and Roly, snogging, petting, rolling in the grass or falling off the sofa, discussing marriage, arguing about Freud, going off with other people, getting back together again, punishing each other with bites and slaps and harsh words, as they struggle to contain their frustration over the non-consummation of their love. The struggle energises the narrative, turning the pages of the book to the insistent, teasing beat of will-they-or-won’t-they?

(Spoiler Alert: the introduction you are reading will give away the ending. If you think this might spoil your enjoyment, then I suggest you stop reading the introduction now and go straight to the novel. You can come back to the introduction later. Personally I always do it that way round. ZF)

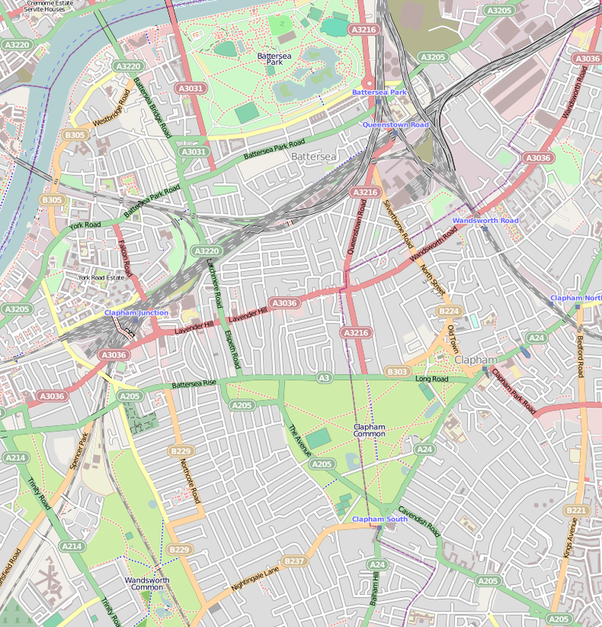

Pamela Hansford Johnson was born in 1912, the daughter of Amy Clotilda née Howson, an actor and singer with the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, and Reginald Johnson, a colonial administrator who worked as chief storekeeper on the Baro Kano Railway in what is now Ghana. He was frequently absent, and she grew up with her mother’s family of actors and theatrical administrators in what she describes in the first of the autobiographical essays contained in her book Important to Me, as “a large brick terrace house”on Battersea Rise. The house had been bought by her grandfather in the 1880s, a time when “it looked out on fields where sheep might safely graze. But by the time I was born, the railway had come, and the houses had been built up right over the hills between it and us. Not pretty, I suppose.”

In 1923, when she was 11, her father, home on a visit, was found dead in the downstairs loo by Pamela’s mother’s sister, who had once been in love with him. In an essay entitled “A Sharp Decline in Income” (all essays referred to in this introduction are from Important to Me), Pamela Hansford Johnson describes how the resultant poverty, combined with the Bohemian lifestyle of her mother’s theatrical family, and their snobbery (they referred to the part of Battersea Rise in which they did not live as “the other Battersea Rise”, and “the thought of ‘marrying into trade’ afflicted them as it might have afflicted a noble Victorian”) led her to think that she was “of no recognisable class.” Her mother worked from home as a typist, and took in lodgers. Pamela was only able to stay on at Clapham County Secondary School (fees £5 per term) through the charity of the governors, and university was out of the question.

In retrospect, she did not see this as a hardship: “to a creative writer, a university education would have been nothing but a hindrance,” she wrote, in her essay A Higher Education. “A course in Eng. Lit. has rotted many a promising writer.” As a critic, however, she acknowledged that university education might have been helpful.

She left school at 16 and took a six-month training course at the Triangle Secretarial College in South Molton Street in the West End. Her first job was as a stenographer at the Central Hanover Bank of New York in Lower Regent Street: the money was meagre, and most of it went to her mother for her keep. In A Sharp Decline in Income, she describes the joys of pay day, of being able to afford “an omelette, chips and blackcurrant sponge pudding” for lunch, instead of her usual cup of tea and a bun.

To supplement her wages she wrote and published short stories and poems, winning a poetry competition in The Sunday Referee. The prize was a subsidy towards her first poetry collection, Symphony for Full Orchestra, which came out in 1934. She became involved with of a group of young writers who met at the home of the journalist Victor Neuburg. These included Dylan Thomas, to whom she became engaged.

She was working at the time on her first novel, then called Nursery Rhyme. It was Dylan Thomas who suggested the change to This Bed Thy Centre. In her Preface (written in 1961 and included in the Five Leaves 2012 edition), Pamela Hansford Johnson admits to second thoughts about allowing him to influence her into making the change. Her biographer Ishrat Lindblad agrees that Nursery Rhyme would have been more appropriate: “In this book the author is essentially concerned with describing the break from the nursery world that adolescence involves, and in order to emphasise this theme she has woven references to several well-known nursery rhymes and fairy tales into the novel.” Elsie chants “one, two, buckle my shoe, three, four, open the door” to herself as she tries to imagine her future as an adult woman. When she meets Roly’s scary aunt, she can only think, “what great teeth you have, Grandmamma.” Chapter headings include The Silver Nutmeg, and Heigh-ho, says Roly.

Heigh-ho indeed. Realising that the only way he is going to have sex with Elsie is by marrying her, Roly does just that, and the book ends on their wedding night with Elsie alone in bed, awaiting her bridegroom. She feels fortified by her change of status and her expectations of the experiences to come – “she moved her legs beneath the clothes to feel the power that stirred her” – but unaroused and lonely: “for companionship she put out a hand to touch her own shadow on the wall.” Roly’s hand, in the meantime, is on the handle of the door. And so the novel ends. Will he turn out to be a sexually imaginative lover, tender, passionate and seductive? Or a clumsy lout claiming his rights? It is left to the reader, who has followed the couple through their courtship, to imagine the next stage.

This lack of explicitness cut no ice with a disgusted Daily Express: “Miss Johnson,” sneered its reviewer, “will be able to write when she has persuaded herself that there are other things in the world besides sex.” The Times Literary Supplement was almost as disapproving, suggesting that the author “has apparently yet to learn that ‘realism’ does not necessarily deal only with the unpleasant side of life”. Richard Church, writing in John O‘London’s Weekly described the book’s setting as “a world of drunken and lewd suburbia, filling the reader with nausea and speculation as to whether the Hour of Sanitation will come and flow over and obliterate the squalor of scenes in pubs and back streets and the minds of pimply, adolescent girls.”

The book was banned from Battersea Rise public library, anonymous abusive notes were shoved through 23-year-old Pamela’s letter box, and relatives refused to speak to her. She found her sudden notoriety hard to take: “I had not known,” she wrote in her essay about her relationship with her mother Amy, “that it would bring me such misery. The book was not at all autobiographical, but… I believed that it told the truth, so far as any girl of twenty-one, carefully nurtured, knows what the truth is.” She became “sick with fear lest (the book) should become a subject for prosecution.”

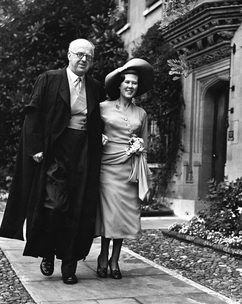

Consolation came in the form of good sales, and a warm review by Cyril Connolly in the New Statesman and Nation, which, noting that “the characters revolve round the bed and the bottle”, admired the grasp the author had on their dialogue and circumstances of living, as well as her “comprehension and sureness of touch.” Connolly invited her to meet for a drink, plied her with beer, reassured her and generally cheered her up. She drew further comfort from the unswerving loyalty of her mother, but found her then-fiancé Dylan Thomas (who was yet to attain the success for which he was destined) less than enthusiastic. In her essay Dylan she describes how she came to realise from his and his friends’ behaviour towards her, that “I was not wanted. I was no longer of their kind. That I had written a successful book made it, for Dylan, worse. Like Scott Fitzgerald, I don’t think he wanted another writer in the family.” Their relationship ended and, in 1936, she married the Australian writer Gordon Neil Stewart. They divorced in 1948, and in 1950 she married the British writer C P Snow.

This Bed Thy Centre launched Pamela Hansford Johnson on a distinguished literary career which included 28 novels (two of them pseudonymously co-authored with her first husband), as well as drama (some co-authored with C P Snow), criticism, literary translation, autobiography and social commentary. Most of her work is now out of print (exceptions are the new Five Leaves edition of This Bed Thy Centre, as well as The Unspeakable Skipton, which is available from Carlton Books, and An Error of Judgement which was republished by Capuchin Classics in 2008), but copies of her titles may be found in second-hand shops, or on the shelves of book-lovers of a certain age. Many can be obtained through www.abebooks.com

Her biographer Ishrat Lindblad ends her book Pamela Hansford Johnson with the words “It is clear that she made a significant contribution to the art of fiction, having written at least a dozen novels that will continue to demand respect.” It’s not exactly a ringing endorsement – do you hunger to read a novel that merely “demands respect”? Neither do I. But if you are drawn to a haunting, bittersweet and sexy evocation of young love, set against an atmospheric backdrop of south-of-the-river suburbia in the years between the world wars, This Bed Thy Centre is for you.

Further Reading

Pamela Hansford Johnson: Important to Me Boston: Scribner’s, 1974

Ishrat Lindblad: Pamela Hansford Johnson Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne, 1982

The reviews cited of This Bed Thy Centre appeared in the Daily Express, 11 April 1935; the New Statesman and Nation, 13 April 1935; the Times Literary Supplement, 25 April 1935.

All rights to the text remain with the author.