Valentine Cunningham

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

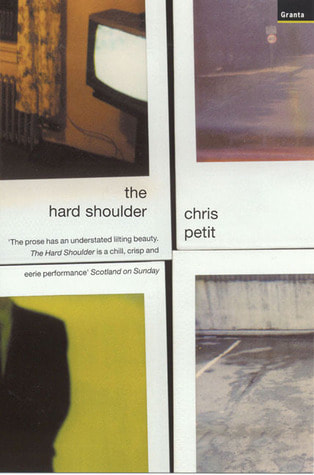

Chris Petit is a hard-eyed documentarist of the city in film and in fiction, the recorder especially of modern London. His credits include being a great ally and aesthetic associate of Iain Sinclair, the CEO of contemporary London writing and film-making. Petit is especially drawn to violent city low life, the doings of urban bad-men – criminals politically motivated, as in his novel of the Northern Irish Troubles The Psalm Killer, but mainly criminals who are criminals out of mere and sheer wickedness, of evil even. The result is seriously good urban thrillers, fiction-noir of the hardest-boiled kind. And The Hard Shoulder, Petit’s Kilburn-noir effort, is at least as good as his Will Self-ish Soho novel Robinson, his Belfast novel The Psalm Killer, and his New York horror-comic cop-fic Back from the Dead.

Petit’s fictional territory is what Iain Sinclair has labelled the ‘psychogeographical badlands’; in the case of The Hard Shoulder, Kilburn and its environs and hinterlands. It’s as if Sinclair’s favourite East End, Jewish criminal, Kray Brothers’ London has been shifted northwards and westwards to Irish (Catholic) criminal NW6. This Kilburn is the loving habitat of O’Grady, one-time local hard-man, just out of prison where he’s done ten or so years’ time for being the getaway driver in a botched hold-up job.

Petit’s fictional territory is what Iain Sinclair has labelled the ‘psychogeographical badlands’; in the case of The Hard Shoulder, Kilburn and its environs and hinterlands. It’s as if Sinclair’s favourite East End, Jewish criminal, Kray Brothers’ London has been shifted northwards and westwards to Irish (Catholic) criminal NW6. This Kilburn is the loving habitat of O’Grady, one-time local hard-man, just out of prison where he’s done ten or so years’ time for being the getaway driver in a botched hold-up job.

This ex-con is soon being cruelly pressured by a creepily know-all gangster chum Shaughnessy and his broken-kneed alcoholic sidekick Tel to put the squeeze on godfather Ronnie, now living a lush life on the Costa del Crime, partly on O’Grady’s share of the loot from the messed-up raid. O’Grady is most reluctant to get back into the old ways. He prefers serving the breakfast at his pious sister Molly’s ‘hotel’, going to the pictures with the sexually eager housemaid Kathleen, and visiting his old mum in a Home in Willesden. He’s emotionally screwed up, crippled in fact, by guilt over the little girl he ran over and killed in the getaway car, and about his own lost daughter Lily from his broken marriage, same age as the little girl he knocked down. But he’s inexorably sucked into replaying the old violent games, which involve hunting down Lily and her rough-and-ready rock musician boyfriend in their flash pad in posh Totteridge, and a black-comic attempt by the bad-boy trio O’Grady, Shaughnessy and Tel to kidnap Lee, Ronnie’s rich little brat of a daughter, out at Ronnie’s mansion near Lambourne End in hopes of extorting the ill-gotten that’s owed, money O’Grady has promised to Lily.

Violence and violent death impinge menacingly from the start of the novel and home in on O’Grady with terrifyingly needy accuracy. In Ronnie’s pay, Shaughnessy obtains – with the help of a pair of Upper Holloway heavy-plant hirers connected to the IRA – a mouthy young Northern Irish hit-man called Brendan to bump off O’Grady, but the ‘thick’ Mick misfires, managing only to wound his target. Disgusted, Shaughnessy offs Brendan (a ‘clot’), and has a go at O’Grady himself, but fails ludicrously, even though assisted by the jumpy Tel armed with a big knife. He opens fire at his own mirror image in Molly’s bedroom, from which O’Grady is happily absent. It turns out that Shaughnessy has a bad heart and he kicks the bucket in Ronnie’s crappy Essex seaside bungalow to which the kidnappers have resorted as a miserable safe-house. Ronnie is arrested as he lands at some private airfield, the cops beating O’Grady to the man who might have the money. O’Grady robs an Asian post office for lamentably small pickings, which he hands over to the rather surprised Lily. He dies at the end, it would seem, at the wheel of Ronnie’s Merc, the gunshot wound in his side finally doing him in, fantasizing the while about fun for Lee and getting to Florida, where sister Molly is moving to run a motel. It all makes for a blackly comic low-tech krimi, which wryly milks the fabled bad luck of the Irish to most attractive effect.

You can feel what’s coming right from the opening page. How repro Grahamegreenish (to use Auden’s label) can you get?

O’Grady, a big man once, stood in the empty carriage of the silver train as it moved faster through the long tunnel from St John’s Wood into daylight at Finchley Road. He wore an overcoat but looked like a man that rarely did, and the battered holdall at his feet was far from full. He stood awkwardly, waiting for the doors to close, blinking at the light after so long underground.

After West Hampstead the train travelled a ridge. Slate sky bled the colour from the view. To the left he could see the tower of the Kilburn State cinema, like a small finger of Manhattan stuck into the London skyline. O’Grady felt his stomach contract and thought of riding on, but he got out at Kilburn, pausing to watch the train move away down the long, straight track. He couldn’t remember if the carriages had always been silver.

He took the stairs down to the street. He was still unfamiliar with the process of everything and whatever he did felt like it was at the wrong speed, even handing in his ticket to the unmanned booth. Outside, the two railway bridges, cutting the road at an angle just above the station entrance and booming whenever a train passed over, were his first familiar landmark. To his left Shoot Up Hill ran up towards Cricklewood. To think he had once aspired to Cricklewood. O’Grady turned right.

The Kilburn High Road had been a ditch when he left, and still was from what he could see. He wondered if Morans, where he’d had his first job, was still there. It was, the same….

Further down on the other side was the Black Lion. He had favoured the Black Lion after being barred from the Roman Way for brawling.

Petit is superior at grab-you openings. This one is as impelling as any of Graham Greene’s inductions into modern threats – as it might be Brighton Rock, Greene’s thirties novel about gang-warfare in Brighton. Petit looks over his shoulder knowingly at Greene’s sort of Ealing Comedy, Best of the Brits version of the hard-boiled thriller, as much as to the great American Chandler-esque tradition it’s also referencing. Precedent literature calls. That ridge the train travels after West Hampstead is surely meant to grapple your readerly attention like the bump in the Manhattan street in the opening of Martin Amis’s great novel of urban corruption Money (1984), which reaches out to catch the hero’s cab like a ‘grapple-ridge’. And of course there’s a business called Morans: we assume they’re members of the clan that Moran the longsuffering narrator of Samuel Beckett’s Molloy belonged to. In literary terms this is very street-wise; which is apt, one might think, to this highly street-wise – in every sense – fiction.

Wise, especially, about streets. With our Rip Van Winkle ex-con we’re plunged straight away into the territory that will be devotedly mapped: the cartography of Kilburn – Finchley Road, Shoot Up Hill, Kilburn High Road. Those roads will spread out and around into the suburbs and Essex, but Kilburn’s the epicentre of the novel’s mapping – Petit’s version of what Iain Sinclair has in Lights Out for the Territory called the ‘alternative cartographies of the city’ (phrase from a Chris Jenks essay on ‘The History and Practice of the Flâneur’). Sinclair heralded such doing in a catalogue of alternative London cartographers in Lights Out, a sort of canon of commendable rescuers of London ‘dead ground’ – J.G. Ballard, Michael Moorcock, Angela Carter, Peter Ackroyd, Alexander Baron, Emmanuel Litvinoff, Bernard Kops, Stewart Home. Petit, a recurrent presence in Lights Out, is of course in the list – meeting a ‘fetch’ of Robin Cook (ie Derek Raymond) as he ‘minicabs between Soho and the suburbs’.

The generous alternative cartographics of The Hard Shoulder are done in a kind of detailed A-Z guide to unglamorous London. This is revelatory, documentary, realistic text as an A-Z. We’re driven with O’Grady and Shaughnessy ‘over the Harrow Road and across the top of North Kensington… down North Pole Road… turn left at the junction of Scrubs Lane… [then] right into Du Cane Road’, en route to see Ronnie’s mate John in Wormwood Scrubs prison.

They crossed three of the roads that O’Grady had always thought of as the great divides, the Kilburn High Road, the Finchley Road, then, via the back-streets of Chalk Farm and Kentish Town, the Holloway Road, always to his mind the most sullen of the lot. He … recalled going as a child with his mother to the Jones Brothers department store and her telling him they were on the edge of the land of the darkies, and the frequent threat of punishment of being sent there to live with them.

Once they were in the Seven Sisters Road most of the shops became open-fronted stores with vegetables on display. In Kilburn a greengrocer was a rarity. …

Shaughnessy made him turn left up Hornsey Road, which was clogged with traffic. They inched past the baths, with a big painted sign of a diving woman in a bathing suit …

Further up the road was a big police station. Shaughnessy kept nervously clearing his throat, and O’Grady wondered if he was wanted or had form ….

There’s a lot of driving around in Shaughnessy’s rotting Datsun, much of it as O’Grady makes his parodically slow car-chases in pursuit of his lost women and elusive loot. O’Grady does some walking, but not a lot; he’s a twentieth century parodic upgrade of the Baudelarian flâneur, who embraces the urbs and suburbs mainly by courtesy of a decaying internal combustion engine. Round and round he and we go, motorized, but slowly, getting farcically to know the ‘dead ground’ of Sinclair’s list – modern, even super-modern non-places, as they’ve been called (in Marc Augé’s Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, about living in the ‘non-space’ of supermarkets, airports, hotels, motorways; or in John Burnside’s novel about Corby, Living Nowhere): the banal England of the North Circular, of Wembley, of Harlesden, and such. Places where not a lot happens to glamorize them out of tedious flatness. Where even the bloodletting is pale stuff. Characteristically, at the South Mimms service station the planned exchange of Lee for Ronnie’s cash fails to happen. ‘Wembley struck O’Grady as one of those places that were too far from the centre to count and not far enough out to have any point of their own’. He ‘wasn’t even sure where they were. Kingsbury or Queensbury, maybe even Canons Park. It no longer felt like the suburbs, more like the suburbs of the suburbs. He managed to locate a municipal car park near a shopping centre with toilets that turned out to be locked’. They finally catch up with Lily and her rock-musician on the Staples corner flyover of the North Circular after cruising haphazardly along the Barnet by-pass, and head for Harlesden. ‘ “What the fuck’s in Harlesden for the likes of them?” ’. ‘He followed the Mercedes to a turning off Old Oak Lane, close to the railway sidings, not far from the prison where they had been earlier that day’.

Their destination ‘looked like an industrial shed stuck on a trading estate’. A place for a rave, which is one of the many new things which have come along while O’Grady was inside. ‘Thousands cram into them and they all take a happy pill and jig up and down to loud music. Sounds like hell to me’, Shaughnessy informs. O’Grady doesn’t dissent. The old London awfulnesses he was used to have certainly had their upgrades, but their modernizings are never less than concerning to our Rip Van Winkle as he ticks them off on his return, like Lazarus, from the tomb of prison. The big dance hall where he’d spent his disappointing Saturdays chasing Irish girls, optimistic condoms in his top-pocket but never used because the girls were well-coached in mortal sin, is now an even more discomfiting place for oldies’ dance-classes. Byrne’s newsagent is Byrne’s only in name now; disconcertingly, an Indian runs it (‘ “Where’s old man Byrne?” ’ ‘“I’m Byrne now”, said the man brightly’).

What Petit is putting on the map is what Sinclair relished in the writing and films of Petit lookalike Patrick Keiller as ‘the underdescribed quarters of the city’. Petit is rescuing neglected Kilburn and its hinterland for fiction, inventing it for new aesthetic consideration, as Dickens invented London’s East End, Mrs Gaskell invented 1840s Manchester and Alan Sillitoe 1950s Nottingham. Petit keenly maps out the telling urban stuff, the revelatory streets and their furniture, the local pubs (always known as locals) and their local inhabitants, and the buildings which are the large signifiers of local meaning. These local truths of the locale are the penetralia of understandings utterly beyond the scope of the outsider, elusive to the keenest-eyed visiting anthropological observer and documentarist, and especially to the novelist as slummer. This is psychogeography as inside story. That Kilburn State Cinema which the narrative notices on the opening page, with its unmissable tower (modelled on the Empire State Building), the once nationally famous Gaumont picture palace of the Kilburn High Road, opened in December 1937 with an astounding 4,000-plus seats: O’Grady’s been in there, and he goes inside its now reduced modern state later in the novel with Kathleen to see Silverado, a newly released Western of 1985.

This is insider trading, courtesy of Petit’s minute local knowledge and experience, and we are repeatedly inducted into it. We’re let into the Black Lion, for instance, first port of call for the released O’Grady, and for us. ‘It was soon after opening and the place was empty apart from a couple of biddies in a corner chasing bottles of stout with what looked like sweet sherry…. the barman was a surly lad more interested in his paper than pouring Guinness. O’Grady asked for a Jameson’s too, to give him something extra to do’. Come Sunday lunchtime O’Grady’s in there again, sipping the Jameson’s, putting money in the IRA collecting tin, bearing with Shaughnessy’s boasts about a pal who’s got a crate of Jameson’s ‘for a very fair price considering’. O’Grady haunts pubs, essential to him in every way. In one on York Way he taps an old chum the barmaid Carole for information about his wife’s whereabouts and enthuses about the satisfactions of the local. ‘She fixed a vodka from one of the bottles hanging upside-down behind the bar. Those bottles and their optic measures summed up for O’Grady what was most satisfying about a pub: the promise and choice, the endless permutations and rituals to the straightforward objective of getting plastered.’ These trips inside these ordinary proletarian spaces is a reminder of what Sillitoe did in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.

This is dull reality made arresting through Petit’s confident deictic, pointing-out practice: the shared knowability of London which Dickens made his own. It’s the kind of close-up pointing out of realia which takes place, for example, when in Oliver Twist Rose Maylie and Mr Brownlow meet the fallen woman Nancy on the stairs on the Surrey side of London Bridge, and are spied on by Noah Claypole – ‘just below the end of the second’ flight of stairs, ‘going down’, where ‘the stone wall on the left terminates in an ornamental pilaster facing towards the Thames. At this point the lower steps widen: so that a person turning that angle of the wall, is necessarily unseen by any others on the stairs who chance to be above him, if only a step’. This is the verity of the photograph. You could go and check it out for yourself. Just so, The Hard Shoulder keeps pointing to touchable, knowable places. Look there, come here, it says; follow O’Grady to this place – that rave shed in Harlesden, it might be, ‘off Old Oak Lane, close to the railway sidings, not far from the prison where they had been that day’. Locations located and locatable, utterly knowable in the confident epistemology of this narrated city, possessed by those unwavering definite articles and demonstratives. The railway sidings, the prison, that day. O’Grady knows which, where and when; like his author. Petit has been there, and takes you the reader there, and you could indeed go there to see for yourself. Which is a fine realistic assumption and practice: the realistic Dickensian prose mode the English novel was initiated into by Daniel Defoe (that Londoner who founded the English novel in masterly mappings of his home city). An utterly assured pointing prose, showing us this, that and the other, as they are: ‘one of the bottles hanging upside-down behind the bar. Those bottles and their optic measures… the promise and choice, the endless permutations and rituals to the straightforward objective of getting plastered’. This is unflustered, lucid prose which knows what’s what and where, keeps registering how things are and how they’re done. (The prose George Orwell did his best to work with.) And particularly revelatory about being, about selfhood, in this London of the novel’s mid-eighties setting, especially as they’re affected by money and class-consciousness and how they get expressed in bricks and mortar, bigger and better barns (as the Good Book has it), slicker motors, changings of place.

Much of the novel is about social and economic aspiration and upgrading, as signified by moving house, the acquisition of property, moves into better streets, better parts of town, leafier suburbs. O’Grady’s sister Molly is buying up houses. His ex-wife Maggie has up-shifted to Stanmore, along Honeypot Lane – a modern development , ‘executive style’ cul-de-sac, houses widely spaced, place as ‘empty as a dream’, out by the ‘big American-style supermarket’ with ‘its own road and shrubbery’ and the feeling ‘of driving into some private estate that let you take things out’. Crooked Ronnie is building bigger and better in city-edge footballer territory. This is loadsamoney Thatcher’s Britain (she’s almost local, MP for Finchley, ‘just up the road’, as O’Grady’s mum knows). It’s the dubious new prosperity-time enjoyed and exemplified most of all by Lily’s nasty rock-band boyfriend and Ronnie the villain who’s made his money by crime.

Petit knows the territory and how to convincingly chorograph – as well as choreograph – its bristling blend of the ethical, economic, social and political. Chorography, the writing of urban settlements, which has run continuously as a main fictional business alongside biography, ‘written lives’, ever since Henry Fielding offered them in Joseph Andrews (1742) as rival models for his new mode, the novel in English. Petit is wonderfully cunning, slyly laconic even, in his managing of his biographies and chorographies. O’Grady’s story, his past and his present, are eked out in a canny, slowly built-up, hint-full narrative. It’s full of lovely, ordinary, banal Londoner lingo, so revealingly outspoken, but like the novel giving away just enough, never too much at a time. This is the narrating of urban and suburban spaces and spacings which speaks eloquently not just in and about those spaces but in the astute gaps between them. Petit’s style exemplifies his fondness for the film-maker Wim Wender’s narratological recipe: ‘The story should unfold in the spaces between the characters’. Petit is such a good manager of his diverse materials and their presentation. In Lights Out for the Territory Sinclair lauded Petit’s novel Robinson for its ‘ex-film director’s grasp of essentials’ – the essentials of urban truth-telling. And that’s the essential truth about Petit’s truth-tellings: his sure grasp of the essentials of a certain place and its people, its economics, history and ethics and, not least, his grasp of the generic needs of a (London) noir thriller.

Valentine Cunningham: emeritus Professor of English Language and Literature, Oxford University, and emeritus Fellow in English Literature, Corpus Christi College, Oxford; psycho-geographer manqué; writes about fiction, new and old, literary theory, Shakespeare, the Victorians, Modernism, Spanish Civil War literature, the Bible; is still dragging along the awfully slow length of an A-Z Guide to Robinson Crusoe and all its doings and manifestations: ABCDEfoe: A Lexicon for Robinson. (Snappy title, at least, he says….)

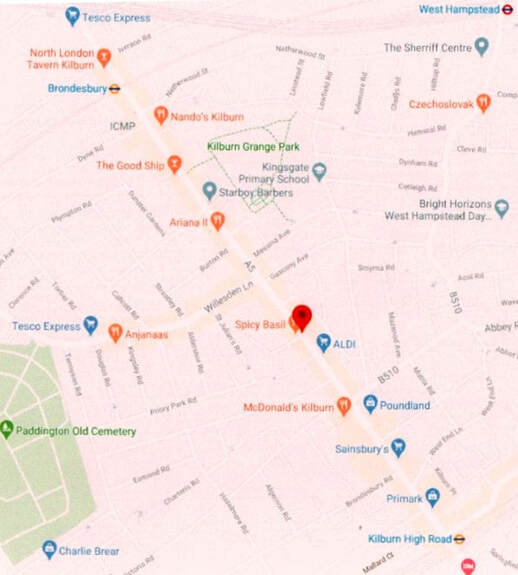

Kilburn High Road

Following Irish O’Grady’s 1985 footsteps along Kilburn High Road is quite easy. Much has changed, even in the few years since the novel’s 1980s, but the main landmarks and ports of call, as it were the bone-structure of the place, are still intact enough to be recognisable.

This is the A5 out of London, a log-jam of traffic slewing up and down a perceptible slope. It rises more sharply at the top end leftwards out of the Jubilee Line station, up Shooter’s Hill to Cricklewood (posher once, O’Grady tells us, though not really posher now). O’Grady turned right out of the station, wondering whether Morans, where he’d had his first job, would still be there. It was; and still is; on the right, just a little way down. M.P. Moran & Sons Ltd, a Builders’ and Timber Merchant, selling tools and plumbing stuff, with large Bathroom showrooms. It’s the last of the Road’s big stores. Its one-time big companions, B.B. Evans, Woolworths, the British Home Stores, have all, alas, gone. Shopping here is not what it once was.

Once the road was a spectacular shopping drag, a ‘ditch’, as O’Grady puts it, walled in by great fetchingly square five-storey blocks, many with ornamental eaves, all loops and arabesques and machicolations, housing three hundred or so shops. Solid, bourgeois and petit-bourgeois citadels of purchases they were – the big departments, smart grocers, wet-fish shops, coffee and tea emporia, several Sainsbury’s, Lyons teashops (Foyles began in Kilburn) – interspersed with ornate banks, grand pubs, cinemas, the big dance-hall (one-time cinema) which O’Grady remembers from his youth. Kilburn High Road was renowned for the domes which crowded its skyline. M.P. Moran’s two domes survive, as does Lloyds Bank’s, and the old dance hall’s. The pubs mainly survive as well: the Sir Colin Campbell (named for the hero of Lucknow); the Greene King (‘Licensed 1486, rebuilt 1900’ it proclaims); the Black Lion, in which much of the novel’s drinking takes place (‘Rebuilt 1898’), a listed building which entirely merits its place on Camra’s Historic Interiors Inventory; and many more. 1898 and 1900 sing out proudly on those pubs. This settlement was clearly entering its heyday then. The many side roads are crammed with substantial late-Victorian, Edwardian houses.

But how the shops have changed. Now they’re dominantly bazaars of ultra-contemporary need – Botox parlours, Sports Direct, Vodafone, Laser Hair Removers – neighboured by the pitiless flagships of urban economic decline, grim tokens of a citizenry hanging in there, but only just – pawnbrokers, cheapo household good marts, Poundland, Everything £10 or Less shops, instant money sharks – Pay Day Loans brazenly offers money at APR 319.1%. Long ranks of brightly plasticated ground-floor desperation prop up floor after floor of dingy-looking apartment windows and offices of need – so many solicitors, specialists in immigration problems – or just gloomily empty floors. And if those immigration advisors are outward signs of population change, even more so are the numerous Halal butchers and grocers, a Halal restaurant, and the boxes of exotic veg spilling onto the pavement, all manned, as is the way, by men – middle-easterners and easterners of all sorts, Bengalis, Arabs, Turks, Lebanese. The Road’s Safeways supermarket, which O’Grady favours for his food needs, sticks out now as a rather alien supplier.

Plainly the Irish Kilburn of O’Grady’s and Chris Petit’s acquaintance (‘County Kilburn’ as the area was once known), is legible now rather as a kind of palimpsestic trace. The Road does have, to be sure, a couple of Paddy Power bookies. The Sir Colin Campbell offers Traditional Irish Music Nights. The huge, upturned galleon, Roman Catholic Church of the Sacred Heart in the side Quex Road (O’Grady’s sister’s church, where O’Grady hangs out to meet old chums), still functions. The Irish Centre Housing Association is putting up a huge apartment block opposite. But the Church does seem rather big in funerals, and the St Eugene de Mazoned Primary School next door in Mazoned Road is open nowadays to all religious comers. ‘Irish Times Sold Here’ the metal signs outside a newsagent announce, but they are getting a bit rusty. You can still eat Irish Salt Beef on this Road, but that’s at Woody’s (Lebanese?) Grill, where every other dish is very unIrish indeed. So though it’s not quite a case of everything being, as the Yeats poem has it, ‘changed utterly’, it is a close-run thing.

The big Deco-ish building that was the Road’s dance hall is still intact, but it glooms mysteriously, shut up, apparently occupied, but as and by who knows what. And the Road’s most prominent architectural citizen, the onetime Gaumont State Cinema, is now a branch of the Ruach Inspirational Church of God of Brixton. A form of Christianity very far indeed from the Quex Road Romans. The State was the largest cinema in Europe, a wondrous Art Deco palace, with a vast four-manual Wurlitzer organ which had, notoriously, a grand piano somehow attached. The cinema’s tower, the tallest edifice in this Road of tall buildings, boastfully echoed New York’s Empire State building, whence the cinema’s name. ‘STATE’, the tower proclaimed on three sides in huge letters which lit up at night. The grand opening on 20 December 1937 was broadcast nationally on the wireless by the BBC (Gracie Fields sang, harmonica genius Larry Adler played, as did the BBC’s resident Henry Hall dance band). The State was one of London’s main popular-music venues. Louis Armstrong, Stephane Grappelli, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles all performed there.

Eventually the vast auditorium gave way to a small cinema – O’Grady takes a woman to see a film in it. Now the building resounds only to the Ruach Ministries’ pentecostal rhythms, and that just once a week, on Sundays at 12.30. They’re not too put off, one hopes, by the building’s pavement-level rash, the Beauty Laser Hair Clinic, US Nail Art, Cancer Charity Shop and Hair and Beauty Salon which cluster where once the film posters went, under the crumbling white Deco tiles and the rusting empty flag-pole holders. The great STATE letters are still in place, but they light up no longer.

Here, as on every hand in the Road is manifest cultural shift, even reduction, if not absolute decline and fall (piquantly, Evelyn Waugh, author of Decline and Fall, once lived in Kilburn). But it’s a pervasive declivity that’s greatly alleviated, unexpectedly, amazingly even, by the neighbour that arrived too late to get onto O’Grady’s radar, the wonderful Tricycle Theatre and Cinema – in the adapted and built-on old Foresters Friendly Society building, over the road from the Sir Colin Campbell. The Tricycle’s a brilliant community Arts hub, specialising not just in great superior drama and film but in radical docu-dramas, re-enactments of the Iraq War Inquiry, and such. It’s said that on the Tricycle’s occasional Irish music/film/drama nights the small auditorium is emotionally packed with Kilburn’s residual native Irish.

And daily at the Tricycle, and not just on Irish nights, a kind of beauty, even, to quote Yeats again, a terrible beauty, is born again: cheeringly defiant in the face of the Road’s so many occasions for gloom about change and loss.

References and Further Reading

Chris Petit: Robinson, Jonathan Cape, 1993; The Psalm Killer, Macmillan, 1996; Back from the Dead, Macmillan, 1999; The Hard Shoulder, Granta, 2001

Marc Augé: Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, Verso, 1995

John Burnside: Living Nowhere, Jonathan Cape, 2002

Iain Sinclair: Lights Out for the Territory, Granta, 1997

All rights to the text remain with the author.