Sarah Wise

SPOILER ALERT! This article gives away the most important plot point of Orwell’s novel…

In the earliest of several dream sequences in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith dreams of a dark-haired young woman coming towards him and, with one magnificent sweep of her hand, removing all her clothes. This ‘aroused no desire within him’ we are told, but what overwhelmed Winston was the gesture of ‘grace and carelessness that seemed to annihilate a whole culture – a whole system of thought, as though Big Brother and the Party could all be swept into nothingness by a single splendid movement of the arm’.

In the earliest of several dream sequences in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith dreams of a dark-haired young woman coming towards him and, with one magnificent sweep of her hand, removing all her clothes. This ‘aroused no desire within him’ we are told, but what overwhelmed Winston was the gesture of ‘grace and carelessness that seemed to annihilate a whole culture – a whole system of thought, as though Big Brother and the Party could all be swept into nothingness by a single splendid movement of the arm’.

It was a gesture that belonged to what Winston can only conceive of as ‘the ancient time’, and later on as ‘the olden time’; and as he awakes from this dream, the word that is on his lips is ‘Shakespeare’.

Nineteen Eighty-Four presents in its early chapters a portrait of a consciousness in which the past (that is, the non-Party-sanctioned aspects of it) begins to present itself in fragments: an arm gesture, something called Shakespeare, a desire for a volume of blank, creamy vellum pages on which to externalise and explore these shards of memory. Before long, Winston’s suppressed memories of his mother and her selfless tenderness return to him, firstly in dreams, then in his waking thoughts – revealing a private, enclosed love of mother for child. He also recalls random incidents in which he has witnessed ‘Proles’ showing altruism, concern for strangers, affection for their neighbours – all things that are now unknown among Party members. (Proles – the proletariat – comprise 85 per cent of the population of ‘Airstrip One’, which is how England has been renamed after the great revolution of the mid-1940s.)

All of this begins to provide Winston with some context against which to place the continuous-present of life under the Party. ‘Do you realise,’ Winston asks his lover Julia, in a moment of post-coital calm, ‘that the past, starting from yesterday, has been abolished? If it survives anywhere, it is in the few solid objects with no words attached to them.’

In the dystopian hell that is life in Airstrip One, all past literature and artwork that could have political or ideological significance is either destroyed or altered to fit in with the Party’s rule. That in fact is Winston’s day job in The Records Department at the Ministry of Truth – to re-write past editions of The Times newspaper to eliminate facts that don’t tally with Party lies; and to manufacture historical heroes and incidents celebratory of Party ideology. The original cuttings are then consumed by fire in the Memory Hole.

Two kinds of cultural material are either deliberately or accidentally overlooked by the Party: firstly, any artefact that is deemed to be of interest to the Proles only; secondly (probably unintentionally), old London streets and buildings that survived the dropping of an atomic bomb and the subsequent revolution of 40 years earlier. The desolate brown-coloured slum area, for instance, where Mr Charrington’s junk-shop is situated (to the north and east of where St Pancras station used to be) does not need to be obliterated. Like the Proles, it is beneath suspicion.

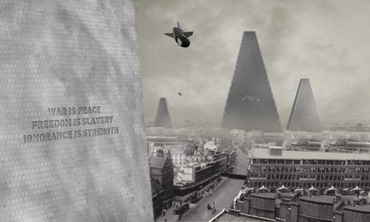

Vestiges of the older city remain – and part of Winston Smith’s reclamation of his non-Party identity is fed by an innate, seemingly ‘ancestral’ sense of a lost London. The ghost of the real London – not the lied-about, reappropriated London – is present all about Winston, and he is haunted by the sense of obscured meaning that locations and buildings have. Orwell has some fun with the inability of Londoners in 1984 to ‘read’ correctly the city’s monuments and buildings, referring, for example, to the horseback statue of Cromwell that stands at the south side of ‘Victory Square’. A statue of Big Brother stands at the top of the tall column in the centre of the square.

The Ministry of Truth, based on Senate House, where Orwell worked in the early 1940s for the Ministry of Propaganda, is one of four massive pyramids of power soaring above the city: Minitrue, Miniluv, Minipax and Miniplenty. Victory Mansions, meanwhile, is believed to be based on Langford Court – the Abbey Road apartment block that Orwell lived in for a while. Like so much of London in Orwell’s novel, this place is both real and unreal, a phantasmagoric version of something that is also commonplace to us today.

Winston knows that the Party doesn’t really need to set about wholesale destruction of London’s landmarks because the campaign against the written word has meant that ruins, statues, inscriptions and street names, if they can be considered impressive, have been officially designated post-Revolutionary in construction. If that lie is too egregious to match the antiquity of the item, it is reclassified under the vague and shady designation ‘the Middle Ages’.

(It’s here that I have to spoil the plot.) We learn, close to the end of the book, that throughout the narrative, Big Brother and the Party have been watching, and indeed instigating and assisting, Winston’s rebellion. From the moment in Chapter 1 when he buys his Edwardian ledger in which to keep his diary of awakening consciousness, through the courtship and love-making with Julia, his wanderings in the Prole districts of London – all this has been connived at by the Party in order to entrap, torture and re-programme Winston. Not to ‘vaporise’ him: that would be too easy and would represent only a partial victory; but to enter and alter his consciousness, so that he will love – genuinely love – Big Brother.

What this narrative means is that the Party fully understands the appeal of antiquity to the likes of Winston. They know that he is (to use Philip Larkin’s phrase) ‘randy for the antique’.

The terrifying reversal comes two-thirds of the way through the novel, when the character who we the reader (along with Winston and Julia) fully believe to be lovely, gentle old Mr Charrington is in fact a Party member and a decoy. Presenting himself as an ancient relic from a more decent former age, Mr Charrington selects characterful paraphernalia from the past that he knows will resonate with Winston. He can lure Winston in because he knows that Winston understands that these pre-Revolution survivors are objects that give proof of another life: a world of individuality, eccentricity, quietness and solitary contemplation (‘Ownlife’ to use the Newspeak term for this seditious activity). Most importantly, these are items that have no use, and The Party is above all utilitarian. Useless, pointless junk, antiques and architectural ruins all speak of a set of human relations that stand outside Party loyalty, hierarchy and power structures.

The object that Winston finds most beautiful is a solid-glass paperweight that he buys at Mr Charrington’s which has a small piece of coral embedded at its centre. Its most powerful allure, for him, is that it belonged to an age that had no conception of the one in which Winston lives. In that sense, it is wholly innocent. The junk-shop is, Winston thinks, ‘a pocket of the past, where extinct animals could walk’. Inherent within its contents are such pre-Revolution, anti-Party phenomena as domesticity, physical comfort, visual pleasure, whimsy. Winston soon begins to wish that he and Julia could exist at the heart of the paperweight in their own eternal cut-off world; Julia separately believes that it is possible within Airstrip One to hollow out your own little world of misbehaviour and dissent that the Thought Police cannot find out about.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four the only escapes from life under the Party occur in small, enclosed spaces. Winston’s emotional solace occurs within, or is referenced by, such enclosures as a human arm (these occur several times as protective gestures), the woodland clearing and the belltower of a ruined church where he and Julia make love, the junk-shop room hideaway, the imagined refuge at the heart of the paperweight. ‘They can’t get inside you,’ Julia had confidently asserted, regarding the Thought Police. But she was wrong. They do indeed enter the deepest recesses of the mind, alter it, and leave Winston loving only Big Brother, and Julia a shattered relic of her former self.

Winston’s body is inhabited by a feeling of privation. Sounds, smells, sights are ugly and the body provides a ‘mute protest’ against the claims of the Party that life is better than it was before the Revolution. Before Julia, the occasional joyless encounters Winston has with prostitutes take place in the dark, earthy, odorous, Prole districts of ‘patched-up 19th-century houses that smelt of cabbage and bad lavatories.’ These streets have been untouched since the Bomb fell in 19FortySomething, and they are very recognisably Victorian streets. ‘He tried to squeeze out some childhood memory that should tell him whether London had always been quite like this. Were there always these vistas of rotting nineteenth-century houses, their sides shored up with baulks of timber, their windows patched with cardboard and their roofs with corrugated iron, their crazy garden walls sagging in all directions?…But it was of no use: he could not remember.’

Prole London is an amalgam of a city Orwell explored more closely than most as a down-and-out – interwoven with the literary representations of London that appear in the works of various authors who influenced him in his early years. Orwell was extraordinarily well read in many writers who had fallen far out of fashion. He plucked George Gissing out of his trajectory into obscurity in the 1940s. He knew the fiction of Charles Reade inside out, when this Victorian literary lion was virtually unread. It is clear that he knew the ‘on tramp’ passages from Richard Whiteing’s slum fiction bestseller No 5 John Street, published in 1899; and he knew Jack London’s vagrancy reportage very well, and W.H. Davies’ 1908 Autobiography of a Super-Tramp.

Orwell himself referenced Mark Rutherford, author of Mark Rutherford’s Deliverance (1885) as ‘one of the best novels in English… that description of the unendurable filth of the slums. The London slums of that day were like that, and all honest writers so described them. But even more characteristic is that notion of a whole block of the population being so degraded as to be beyond contact and beyond redemption.’ Rutherford is the name given by Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four to the cartoonist, whose drawings of slum tenements, starving children, street fighting and capitalists in top hats had helped to foment the revolution.

Orwell himself referenced Mark Rutherford, author of Mark Rutherford’s Deliverance (1885) as ‘one of the best novels in English… that description of the unendurable filth of the slums. The London slums of that day were like that, and all honest writers so described them. But even more characteristic is that notion of a whole block of the population being so degraded as to be beyond contact and beyond redemption.’ Rutherford is the name given by Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four to the cartoonist, whose drawings of slum tenements, starving children, street fighting and capitalists in top hats had helped to foment the revolution.

Influencing the whole lot of them was James Greenwood – the original undercover toff, whose journeys through the street life and institutional experiences of London derelicts began in 1866. Orwell did indeed journey into the London underworld himself, but he also viewing it through the eyes of writers who had made such a huge impact on him in his early years.

Orwell invokes the concept of ‘ancestral memory’ in his depiction of the Proles. The Proles live according to a separate standard. They have retained their integrity, they are eternal and immutable. ‘If there was hope, it lay with the Proles,’ Winston tells himself, just so long as they can be awoken into political consciousness. If they only knew their true power, they could rise up and overturn Big Brother’s hellish Party state.

Winston finally gets to have a conversation with a Prole old enough to recall what London was like before the Revolution. Winston hopes the old man will be a direct link to pre-Revolution experience that would help to suggest a context for the present. This creation of a truthful timeline would, of course, assist plans for future change – which is why the Party has taken control of the past. However, so undeveloped is the Prole man’s intellect, that while he can recall such things as a ‘top hat’, a ‘flunky’ and the House of Lords, he has no opinion on them. ‘The old man’s memory was nothing but a rubbish heap of details,’ Winston concludes. ‘The Proles remembered a million useless things.’ This is detritus emptied of meaning – shards of the past that do not cohere into a narrative with which to take on the Party.

Some of the earliest passages about the Proles are similarly chilly and heartless – possibly because Winston has yet to develop empathy; possibly, though, reflecting the disgust Orwell never managed to shake off with regard to the very poorest. So there are some vile descriptions of the flaunting sexuality of the young Prole women, and the frowsiness of the older women. But as his affair with Julia continues, and his memories of his mother and sister develop, Winston spots a more ambiguous Prole woman. Below the window of Charrington’s junkshop room, a huge bellied, strong-armed, middle-aged Prole woman relentlessly stomps back and forth, putting out her washing and singing the latest pop song that has been crafted by the Party for the Proles (‘It was only an ’opeless fancy…’). As Marcus Smith has pointed out in ‘The Wall of Blackness: A Psychological Approach to 1984’, in the focus on this woman’s ‘fertile belly’, strong arms and warm heart, there may be a hint here that the Proles could outbreed Party members, who have only small families (of children so corrupted that they spy on, and denounce, their own families). The hope that lies with the Proles may be evolutionary.

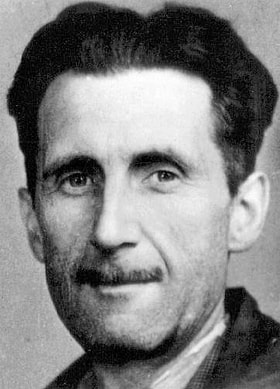

Sarah Wise teaches 19th and 20th century social history and literature to both undergraduates and adult learners. She is the author of The Blackest Streets: The Life and Death of A Victorian Slum (Bodley Head). sarahwise.co.uk

Further Reading

Orwell’s Diaries, 1903-1950, edited by Peter Davison, 2009

James Greenwood, A Night in A Workhouse, 1866; Low-Life Deeps, 1881; The Wilds of London, 1885

Jack London, The People of the Abyss, 1903. (Tangerine Press has recently published an edition with London’s 80 original accompanying photographs, £10/£14 inc p&p.)

Jonathan Rose, ‘The Invisible Sources of 1984’ in Journal of Popular Culture, vol 26, no 1, Summer 1992.

Mark Rutherford’s Deliverance, 1885

Marcus Smith, ‘The Wall of Blackness: A Psychological Approach to 1984’ in Modern Fiction Studies, vol 14, no 4, Winter 1968/9

John Thompson, Orwell’s London (with photographs by Philippa Scoones), 1984

Richard Whiteing, No 5 John Street, 1899

Evgeny Zamyatin, We, 1924

All rights to the text remain with the author.