Angela V. John

A revised version of this article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves in April 2013. You can order it direct from the publishers here.

In the mid-1880s, a well-educated, middle class couple and their baby daughter moved into six rooms at 252 Brunswick Buildings East in Goulston Street, Whitechapel. Today this is London Metropolitan University territory, close to the City and the modern chic of Spitalfields. Then it was a slum area. But these rooms (two self-contained workmen’s flats) had views of the sunset behind St. Paul’s and rent was fifteen shillings and sixpence a week. It was an improvement on their Bloomsbury digs and an invigorating experience.

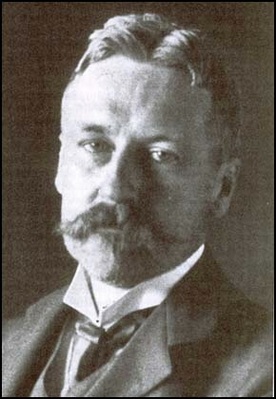

These ‘slummers’ were Henry Nevinson (1856-1941) and his wife Margaret Wynne Nevinson. Their decision to live ‘among bugs, fleas, old clothes, slippery cods’ heads and other garbage’ was inspired by high-minded thoughts. In Henry Nevinson’s case socialism and social reform were paramount. He was, for a time, an early member of the Social Democratic Federation. For Margaret Nevinson, the daughter of a clergyman, the Christian creed was her prime inspiration. Both were attracted by the new experiment in university settlement developed by the Rev. Samuel Barnett round the corner from them in Toynbee Hall and participated in its work.

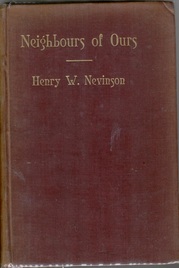

A decade later Henry Nevinson’s collection of what he called ‘Thames Stories’ was published. Entitled Neighbours of Ours, it appeared in Arrowsmith’s 3/6d [17.5p] series. This had already produced such classics as Three Men in a Boat, The Diary of a Nobody and The Prisoner of Zenda along with others that have long been forgotten. The timing was not perfect: Arthur Morrison’s Tales of Mean Streets had appeared a few weeks earlier and stole the limelight. A disappointed Nevinson noted that ‘mine was praised, and his was bought’. He believed that the ‘gleams of brightness’ in his book made it more readable than Morrison’s but that Tales of Mean Streets appealed to people because it ‘flatters the bourgeois idea of the working man’.

Nevinson’s reviewers were impressed. C.F.G. Masterman called it ‘the best volume of tales which ever took as their theatre of action the desolate and fascinating region of the “East End”’ and attributed the book’s realism to the author’s close proximity to his subjects. And although it passed into obscurity in later years, more recently it has attracted attention from literary critics and historians.

Nevinson’s reviewers were impressed. C.F.G. Masterman called it ‘the best volume of tales which ever took as their theatre of action the desolate and fascinating region of the “East End”’ and attributed the book’s realism to the author’s close proximity to his subjects. And although it passed into obscurity in later years, more recently it has attracted attention from literary critics and historians.

Peter Keating (who included two of Nevinson’s tales in his selection of working class stories of the 1890s) dubbed him ‘the first distinctive writer of the Cockney School’. Assessing nineteenth century British short stories Wendell V. Harris calls the collection ‘a treasure’ and Nevinson ‘a master of storytelling’. Its delights ‘deserve to be much more widely known’.

So what does Neighbours offer? At the fin de siècle the short story was very much in vogue as was writing about London’s East End. But stories about London’s poor often favoured the sensational and extreme. Writers tended to depict figures prone to violence or totally bowed down by their circumstances. They were vehicles for their creators’ moral indignation or revolutionary message. In Nevinson’s fiction, however, character matters more than class. Individuality is emphasised as is an acute sense of place. His protagonists don’t think of themselves as failures or types to be labelled and analysed by others and are neither caricatures nor reduced to statistics. Rather than being objects of social pity here are folk in a distinct geographical and social community yet their lives reveal subtle gradations and shifting fortunes. In his diary Nevinson had written that ‘The people were almost as distinct and individual as in a village’. He did not minimise the harshness of the environment but neither did he elide it with its inhabitants.

There are ten stories linked by a narrator and some characters crop up in several stories. We learn quite a bit about those who live in the remarkably modern sounding ‘Millennium Buildin’s’. And the useful device of having the one narrator throughout not only unifies but also guides Dear Reader. Jacko Britton – the working man’s John Bull – takes us around his community, encouraging us to observe and share experiences and witticisms with him.

And there is plenty of native wit here. For a start there are the nicknames, suggestive of Dickensian richness and wonderfully tongue in cheek. Take Tom Brier: ‘we used to call ’im Victoria Park, or just Parky for short, cos ’e was real fond of the country’ or ragged old Groun’sel who sold bird-food ‘’E seemed to be never comin’ from nowhere, nor yet goin’ nowhere else’. Then there is Ned Philips the Cadet, known as Tentpole.

The tales are all relayed in dialect. Demotic language in fiction often can be off putting and patronising. But even though it may help to account for the book not selling as well as Nevinson had hoped, the pervasive humour helps to leaven the effects of using dialect. And he was well aware of his credentials as a first hand observer resident in the area as opposed to someone making a rapid foray into the district.

In an unpublished prose account entitled ‘Suburbansim and the Poor’ Nevinson poured his scorn on those who uttered platitudes about the problems of poverty but remained secure in their suburban lives. Somewhat smugly he ridiculed those who found the poor ‘so interesting’, discussed beautiful schemes for the regeneration of mankind and babbled about ‘green tea and Schopenhauer’ and ‘the poetry of the East End’. When he found a young man trying to ‘improve’ down and outs in an LCC doss house in Silvertown by playing Beethoven and Chopin, he responded angrily: ‘If I had been one I should have gone out & spewed at such treatment’.

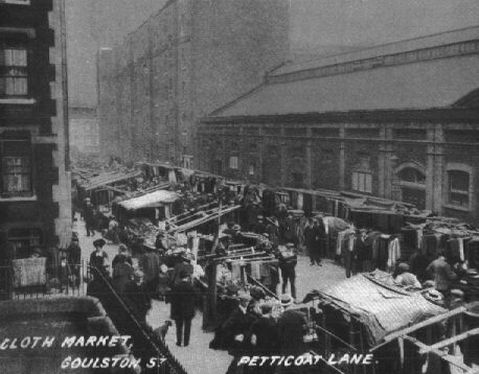

Nevertheless Nevinson was well-aware of his own ambivalent position and by the time he visited the doss house (1893) he and Margaret had decamped to leafy Hampstead where their son (the future artist C.R.W. Nevinson) had been born. Hampstead was too full of the intelligentsia to qualify for the suburban spirit Nevinson so despised but it was still a world away from the environs of Petticoat Lane. Yet the Nevinsons had spent two living in the East End rather than making quick forays and they both continued to do work there.

Most importantly, what redeems Neighbours is the fact that, despite the seductive literary device of the narrator drawing us in, we are reminded that we are ultimately observers who might evince sympathy but cannot fully empathise. Here was the real ‘Abyss’. Nevinson did not underestimate the gulf. He wrote in his diary ‘We can hardly understand the outlook of most of these people, simply dependent for the day’s food on the day’s work and never knowing whether they may get it’.

Yet at the same time he was better qualified than most of his contemporaries to convey the timbre of this world, albeit refracted through the lens of an Oxford-educated solicitor’s son from Leicester. ‘Mrs Simon’s Baby’, a story in which women, the home and neighbourhood networks are paramount may be Nevinson’s version of George Eliot’s Silas Marner but Ellen Ross has noticed that it chimes with a story revealed in Charles Booth’s investigation of London Life and Labour. Margaret Nevinson was a rent-collector for some years and there is some evidence that her experience informed Neighbours of Ours (my emphasis) despite the couple’s increasing estrangement. Beatrice Potter (later Webb) was a manager at Katherine Buildings, one of the model blocks of artisans’ dwellings where Margaret worked. In 1893 Henry Nevinson also visited Katherine Buildings, collecting stories as well as rent. He still taught classes at Toynbee Hall, sat on the committee of a boys’ club and helped to research the building trades for the Industry Series that comprised part of Charles Booth’s massive investigation.

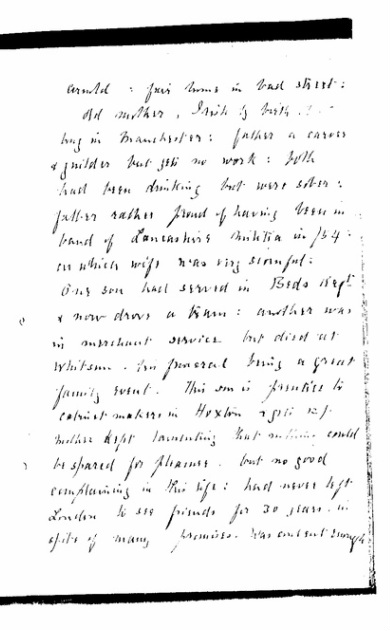

Fortunately Henry Nevinson’s notes from June 1893 have survived and reinforce the veracity of the pictures he paints. A small black notebook in the archives of Shrewsbury School (where Nevinson had been a pupil) supplies names, locations and descriptions of the interiors of homes. For example, the Bates family, a large young family with a grandfather live in one filthy room in Hayden Square in the Minories. It is much decorated with pictures including a portrait of a great-grandfather that had once cost five pounds. In his second story ‘An Aristocrat of Labour’ we are told how Spotter’s father had paid ‘a sportin’ kind o’ sum’, all of ‘five poun’’ for the family portrait. It hung in a big frame ‘with flourishes’ on the wall in his tiny room – a reg’lar one-and-sixer, and dear at a shillin’ – and was its only item except for a bed and a box. In another story we hear about a man called Zulu because he was so dirty. Nevinson’s notes mention a toddler from a filthy Poplar home known as Zulu to the street.

The notes also describe an ‘English common-looking woman with three nigger children’. Her husband was a sailor ‘long away’. Nevinson asks whether she was ‘justified in having a white one before he came back’. Perhaps the most remarkable of the Neighbours stories is ‘Sissero’s Return’ about an inter-racial romance between Ginger (defined yet not judged by colour) and her black sailor husband Sissero. The explicit and crude language of neighbours who do not know how to deal with one of their own choosing such a husband, along with the story’s sexual frankness, make this story remarkable for its time. The community can only see Sissero as ‘Other’: ‘the thing we’ve got to deal with is a nigger, and ’e being black makes a difference’. Sissero goes on a voyage – the community can cope with him at a distance but when he does not return Ginger is impoverished and sleeps with a moneylender to pay her rent. Sissero eventually returns having missed his ship and worked on a rice plantation in China where he lived with a local woman. In contrast Ginger’s infidelity has been prompted solely by financial desperation for her children. But her neighbours choose not to divulge her secret.

The story does reinforce a number of predictable stereotypes. There is the sexual prowess of Sissero the strong stoker and he is always laughing. The Jewish rent-collector is the ‘baddie’. But Nevinson is nevertheless making a bold statement. Just a few years later he experienced at first-hand the second Anglo-Boer War (he was in Ladysmith throughout its famous siege). Unlike most of his contemporaries his fiction encompasses indigenous black Africans. One short story called ‘The Relief of Eden’ exposes and mocks the ignorance of British colonials who brag of racial superiority.

Another story in Neighbours is remarkable. Peter Keating has described ‘The St George of Rochester’ as ‘unlike any working class story that had been written previously’. This is a cross-class romance with a difference. Nevinson recognised the centrality of the River Thames to any understanding of the society he was writing about. Like his contemporary Joseph Conrad he used north-west Kent as the setting for a river story and also deployed the device of the framed narrative. In Nevinson’s story within a story the former captain regales his listeners with memories of his time on a barge and his romance with a lady. It is a remarkably tender tale from the proud winner of the Doggett Badge (the annual sculling race from London Bridge to Chelsea for Freemen of the Watermen and Lightermen’s company. It was known as Doggett’s Coat and Badge Race after its founder, the eighteenth century theatre manager and comedian Thomas Doggett). In 1893 Nevinson had talked to lightermen and noted their excitement about this race.

Few were as well qualified as Nevinson to write about the last two tales in Neighbours with their accounts of cadets. For over a decade he commanded a working class cadet corps, the first of its kind in London. St George’s in the East Company used the quadrangle of Toynbee Hall before moving to Shadwell Basin. They became part of The Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment with headquarters in Southwark. Nevinson’s diaries for the early 1890s are peppered with frequent references to drill. And just as the first tale in the collection takes the reader out of London – to go ‘hoppin’’ in Kent – so the last story moves from Aldgate to Aldershot and the camp life that was so familiar to Nevinson. As a cadet officer he had the freedom (as he admitted in his autobiography) to ‘visit the fellows in their homes without patronage or pretence at doing them good, but merely in the course of Army Regulations’. Such latitude and familiarity also supplied and authenticated the material that formed the basis of his Slum Stories of London (the title of the American edition of Neighbours).

When Nevinson wrote these stories he was in his late thirties. He had already published studies of Herder and Schiller and he followed Neighbours with In the Valley of Tophet: Scenes of Black Country Life. But although selling more copies than its predecessor, these stories lacked the spirit of Neighbours. For Tophet was based on just a cursory glimpse of the Black Country. It was not until the following year that Nevinson seems to have found what he had long been restlessly seeking. In the spring of 1897 he was engaged to report for the Daily Chronicle on a war between Greece and Turkey. A classical scholar who revered anything Greek and was desperate to court adventure, he now embarked on an extremely successful career as a war correspondent. For decades he traversed the world. He continued to write books – producing more than thirty single-authored volumes as well as numerous chapters and many hundreds of newspaper articles.

Yet there remains something irrepressible about Henry Nevinson’s fond tales of life in London’s East End. They remain of immense value to both the social historian and literary critic. But they have a special appeal for those who enjoy reading about London as it is evident that they have been written by a keen observer of people and place who knew how to tell a spirited and witty story.

Angela V. John is Honorary Professor of History at Aberystwyth University. She is the author of War, Journalism and the Shaping of the Twentieth Century. The Life and Times of Henry W. Nevinson (I.B.Tauris, 2006).

For further details of this and her other publications see www.angelavjohn.com

Tracking Nevinson’s Neighbours

Goulston Street, where Nevinson lived for two years in the 1880s, is where the City edges into the East End. It’s in the shadow of ‘the Gherkin’, but has the look and feel of Whitechapel. There’s still a street market – part of Petticoat Lane – but it’s fairly shabby.

Brunswick Buildings, newly built when the Nevinsons moved in, was demolished in the 1970s. Two mansion blocks from about that time remain. There’s little else from that period. At the southern end of the street, at the junction with Whitechapel High Street, an East End institution remains (though not from Nevinson’s era) – Tubby Isaacs’ seafood stall, now standing opposite a halal fast food outlet.

Goulston Street had a tangential part in the 1888 Jack the Ripper murders and resulting conspiracies – though by then the Nevinsons had moved on to Hampstead.

From Brunswick Buildings, Toynbee Hall would have been no more than two minutes walk – along Wentworth Street and across Commercial Street. It’s still there and thriving, a centre of community activity, support, self-help and education. It was founded in 1884 by Nevinson’s friend, Samuel Barnett – mentioned in passing in Neighbours of Ours – who is remembered in Barnett House, an unremarkable block of flats nearby. Both Henry and Margaret played an active part in Toynbee Hall activities.

A more distant connection, along Whitechapel High Street – accessed by the narrowest of entrances alongside a Kentucky Fried Chicken shop – is Angel Alley, home since 1968 to the anarchist Freedom Press (founded in 1886). Nevinson was briefly on the margins of the Freedom group through his relationship with Nannie Dryhurst, one of the stalwarts of the journal from which the group took its name.

Many of the stories in Neighbours of Ours are set in Shadwell, a district which Nevinson knew well. His cadets both drilled in and were in part recruited from this area. Shadwell is not more than twenty minutes walk from Goulston Street, but it has a very different feel. The City seems distant, while the Thames is close at hand.

Very little of the Shadwell that Nevinson would have known survives. The Hawksmoor-designed tower of St George-in- the-East is the main landmark. The church’s interior was bombed out during the Second World War, along with so much else of the neighbourhood.

There are tiny enclaves of terraced houses on and around Cable Street, and the occasional older block of flats. Most of the area, however, is given over to soulless mansion blocks. In Nevinson’s era, the Jewish East End didn’t extend as far as Shadwell. The incidental Jewish characters in Neighbours of Ours are outsiders to the community. The presence of the docks, though, meant that black and Indian seafarers would not have been an unusual sight.

At first glance, Shadwell seems old East End. There’s a pie and mash shop and a boxing gym within a minute’s walk of the station. Another glance reveals how much has changed. Most shops and businesses are now Bangladeshi run. The Britannia pub is a halal chicken joint. On the north side of the railway line, the arches are given over to a range of Bengali stores and supermarkets.

Although Nevinson never precisely located ‘Millennium Buildin’s’, many of the streets he mentioned can still be found: Pennington Street in Wapping, Dora Street in Limehouse, Johnson Street in Shadwell (with the railway arches by which a character in his tales is found dead). There was and is a Shadwell Basin and a Pier Head, just as Nevinson related. – A.W., 2010

References

H.W. Nevinson: Neighbours of Ours (1895), In the Valley of Tophet: scenes of Black Country life (1896), Changes and Chances (1923)

Arthur Morrison: Tales of Mean Streets 1894

Gill Davies: ‘Foreign Bodies: Images of the London working class at the end of the 19th century’,

Literature and History Spring 1988

Wendell Harris: British Short Fiction in the Nineteenth Century 1979

Angela V. John: War, Journalism and the Shaping of the Twentieth Century: the life and times of Henry W. Nevinson 2006

P.J. Keating (ed): Working-Class Stories of the 1890s 1971

Seth Koven: Slumming: sexual and social politics in Victorian London 2004

Ellen Ross: ‘Women’s Neighbourhood Sharing in London before World War One’,

History Workshop Journal, 1983

Extract from Nevinson’s notebook reproduced by kind permission of Shrewsbury School. Two photographs courtesy of the warmly recommended Spitalfields Life website. Thanks also to Tower Hamlets Local History Library for permission to use a photo from their archive.

All rights to the text remain with the author.