Sarah Wise

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers here.

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers here.

‘The original of the Jago has, it is admitted, ceased to exist. But I will make bold to say that as described by Mr Morrison, it never did exist.’ So wrote critic Henry Duff Traill in his review of Arthur Morrison’s novel A Child of the Jago, in the January 1897 edition of the Fortnightly Review.

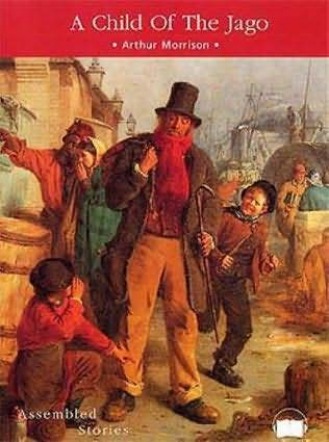

‘The Jago’ of Morrison’s title was the scarcely disguised ‘Old Nichol’ slum, which stood, until the mid-1890s, just behind Shoreditch High Street, on its eastern side. Published in November 1896, A Child of the Jago caused an instant furore. Few reviewers of the novel had failed to be impressed by the power of Morrison’s fiction – the savagery of the depiction of street violence, the pathos of neglected, diseased infants, the scathing attack on high-minded philanthropic interventions; what many refused to accept, though, was Morrison’s insistence that his book had been based entirely on fact.

Traill had continued his assault upon Morrison’s claims to reportage with the words: ‘He invites the world to inspect [the Jago] as a sort of essence or extract of metropolitan degradation… It is the idealising method, and its result is as essentially ideal as the Venus of Milo… the total effect of the story is unreal and phantasmagoric.’ But over the past 100 years, it is Morrison’s vision of that square quarter-mile of East London that has prevailed: his mythic location (‘a fairyland of horror’, in Traill’s view) has usurped the historical fact of the Nichol, which was entirely mundane in its awfulness; and from 1896 onwards, many East London residents have used the words ‘Jago’ and ‘Nichol’ interchangeably. When historian Raphael Samuel came to record days’ worth of cassette tapes with Arthur Harding, who had lived the first ten years of his life in the Nichol’s final ten years, Harding spoke of his childhood in the Jago, as often as he called it the Nichol. This has been one of the most impressive literary re-brandings of a district.

Traill had continued his assault upon Morrison’s claims to reportage with the words: ‘He invites the world to inspect [the Jago] as a sort of essence or extract of metropolitan degradation… It is the idealising method, and its result is as essentially ideal as the Venus of Milo… the total effect of the story is unreal and phantasmagoric.’ But over the past 100 years, it is Morrison’s vision of that square quarter-mile of East London that has prevailed: his mythic location (‘a fairyland of horror’, in Traill’s view) has usurped the historical fact of the Nichol, which was entirely mundane in its awfulness; and from 1896 onwards, many East London residents have used the words ‘Jago’ and ‘Nichol’ interchangeably. When historian Raphael Samuel came to record days’ worth of cassette tapes with Arthur Harding, who had lived the first ten years of his life in the Nichol’s final ten years, Harding spoke of his childhood in the Jago, as often as he called it the Nichol. This has been one of the most impressive literary re-brandings of a district.

Morrison stated that his intention in writing A Child of the Jago had been to show the gradual corruption of a basically decent boy, Dicky Perrott, by the slum in which he was born and grew. ‘It was my fate,’ wrote Morrison in his preface to the third edition of the novel, ‘to encounter a place in Shoreditch, where children were born and reared in circumstances which gave them no reasonable chance of living decent lives: where they were born foredamned to a criminal or semi-criminal career.’ No matter what good impulses Dicky has, no matter any kindnesses shown to him by an outsider, nor any stroke of good luck – he cannot evade the destiny that awaits all who are bred within the filthy streets and noxious moral atmosphere of the Jago.

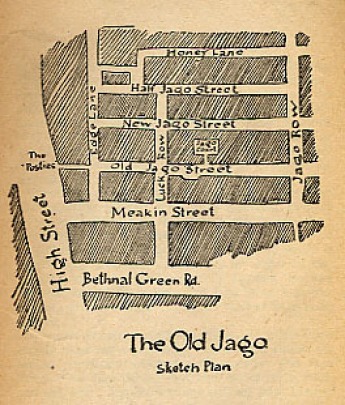

The Old Jago was a direct, street for street, copy of the Old Nichol. Old Jago Street was Old Nichol Street, Jago Row was Nichol Row, and so on. Bethnal Green Road, Shoreditch High Street and The Posties (the narrow alley that connected the Nichol to Shoreditch High Street) all starred as themselves.

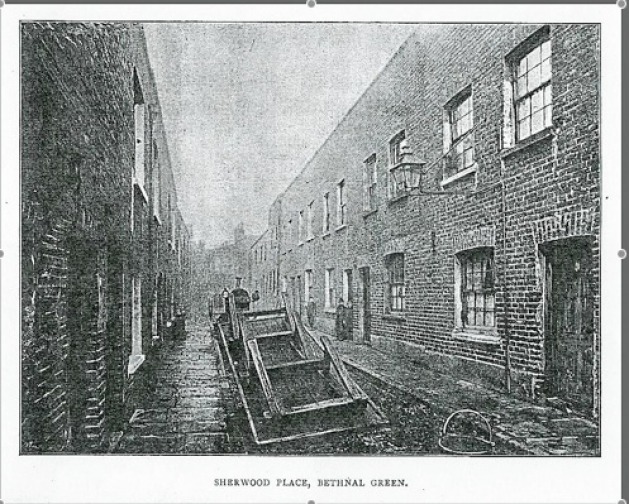

The novel’s action spans nine years; in the first section, Dicky is eight years old; in the second he is 13; and in the third and last, he has reached 17. He grows no older. Inspired by hearing of the real-life killing of 17-year-old Nichol boy Charles Clayton, in July 1892, Morrison has Dicky fatally injured during a gang fight. Clayton, a hawker, of 2 Sherwood Place, had been stabbed in the groin, back and arm, on the night of 25 July, and died four days later, of peritonitis, in the London Hospital, refusing to answer questions about the cause of the brawl or the likely identity of his attackers.

The novel’s 37 chapters are short, snappy scenes (some are barely 500 words long) that drive the plot along at high speed. Meaning never emerges from the story or the characters – the book’s theme is always hammered home, like a Jago fist on a baby’s face.

Dicky’s father, Josh, had been a skilled worker, a plasterer, and has fallen into drink and thieving by the opening of the novel. Dicky’s mother, Hannah, had been born ‘respectable’, outside the Jago, the daughter of a boilermaker; but through flabby inertia and snivelling timidity she has dwindled into Jago life as her husband’s prospects narrow. Dicky is told by an ancient Jago resident, Old Beveridge, that for a child like him, there are only three ways out of the Jago: gaol; death on the gallows; or to join the ‘Igh Mob – the swankily dressed master criminals who have worked their way to the top of the ladder of East End iniquity.

At eight, Dicky attempts his first major theft; he removes the gold watch of a rotund bishop who is taking tea and cake at a self-congratulatory celebration at the East End Elevation Mission & Pansophical Institute (a bitter attack on the real People’s Palace, at Mile End, where Morrison himself had once worked). But instead of a reward, Dicky is badly beaten by his father for attempting such an audacious, unwise ‘click’ (theft) from a toff. This is the first of several instances in the novel of Dicky’s bafflement at the mixed moral messages that press in on him. His mother has told him that ‘You must alwis be respectable an’ straight… ‘an’ you’ll git on then’; his father has taught him that ‘straight people’s fools’, while the example of the ‘Igh Mob suggests that the only Jago people who find any reward on this earth (in fact, the only ones who can keep themselves fed and adequately dressed) are villains. And yet he is larrupped by his father when he pulls off a lucrative click.

Dicky begins to steal for Aaron Weech, an unctuous, hymn-singing Jago shopkeeper who is also a prolific fence. When High Church Anglican vicar Father Sturt (the single influence for good in the Jago, and a portrait from life of the real Reverend Arthur Osborne Jay) spots the potential within Dicky, he arranges for him to start work for a decent, ‘straight’ shopkeeper, Mr Grinder. Dicky proves to have all the makings of a good worker; but Weech, keen to retain his services as a street thief and worried that a reformed Dicky might reveal his fencing activities, engineers Dicky’s sacking. Next, Weech betrays Dicky’s father to the police regarding a theft and assault case, and with the head of the household in jail, Dicky has to steal more and more in order that he, Hannah and his young sister and new baby brother can eat and try to keep warm in their verminous one-room lodging.

Upon his release from prison, Josh hunts down Weech and murders him; Josh is executed, and this completes the work of destroying Dicky’s chances of redemption. After his father’s death he determines that he will ‘spare nobody and stop at nothing… He was a Jago and the world’s enemy.’

Dicky’s story is regularly sent spinning on to a new course by the continual outbursts of faction fighting in the slum. The two clans that dominate the Jago, and to whom all others must pay allegiance (for being neutral is provocative to both sides), are the Ranns and the Learys. Whenever a period of uneasy truce can no longer hold, the entire Jago engages in street battles:

The scrimmage on Jerry Gullen’s stairs was thundering anew, and parties of Learys were making for other houses in the street, when there came a volley of yells from Jago Row, heralding a scudding mob of Ranns. The defeated sortie party from Jago Court, driven back, had gained New Jago Street by way of the house passages behind the Court, and set to gathering the scattered faction. Now the Ranns came, drunk, semi-drunk, and otherwise, and the Learys, leaving Jerry Gullen’s, rushed to meet them. There was a great shock, hats flew, sticks and heads made a wooden rattle, and instantly the two mobs were broken into an uproarious confusion of tangled groups, howling and grappling… Down the middle of Old Jago Street came Sally Green: red-faced, stripped to the waist, dancing, hoarse and triumphant. Nail-scores wide as the finger striped her back, her face, and her throat, and she had a black eye; but in one great hand she dangled a long bunch of clotted hair, as she whooped defiance to the Jago. It was a trophy newly rent from the scalp of Norah Walsh, champion of the Rann womankind.

Sally Green may have been inspired by the Nichol’s Mary Ryan, whom Father Jay described as ‘a virago… a person greatly feared and dreaded in the locality’. But Ryan may also have been a model for Morrison’s character Mother Gapp, owner of the Jago’s most foetid pub, The Feathers – itself based on the real Prince of Wales pub, at 52 Old Nichol Street.

Additional excitement arises from the role that the streets of the Jago themselves play. The maze-like configuration of the Jago/Nichol street plan appears both to influence behaviour and to reflect emotional states. The topography of the Jago induces a cunning, furtive mentality; the possessor of that mentality, in turn, learns to make use of the Jago’s intricacies to evade hostile ‘outsiders’ in pursuit. In Morrison’s book, knowledge of Jago geography is knowledge of evil.

The Jago is first shown impeding Dicky’s movements. As he strolls into view, in the opening pages, he is bumped into by two Jagoites hurtling round the corner of Jago Row, having robbed an unconscious man, just after midnight. Dicky then has to fumble his way carefully along the dark passageway of a tenement so that he doesn’t tread on any aggressive drunk who might be lying there. Physically, as well as morally, Dicky, in several episodes, finds himself hemmed in by the Jago, his actions severely circumscribed. Later on, he must be ‘careful in his lurkings’, avoiding routes used by the Dove Lane (Columbia Road) Gang, who will attack a Jagoite on principal for straying too close to their territory. Dicky’s mother, meanwhile – despised in the Jago for the vestiges of respectability that still cling about her – plans a safe route from her home to a nearby grocery shop. (But Hannah and her baby are viciously assaulted by Sally Green as soon as they leave their door.) Dicky also travels along his own private pathway through the slum when he is in need of emotional solace, to the tiny yard where his only confidante lives – an exhausted old donkey, so famished that it has taken to gnawing the wood of the yard’s palings.

Time and again in A Child of the Jago, characters crash into each other as they burst into the slum, or dash round a corner, or erupt into a court. We also see Dicky expertly negotiating the Jago labyrinth (the ‘foul rat runs, these alleys, not to be traversed by a stranger’) in full flight whenever he has committed a theft. This underlines his ambivalent relationship to the place: Dicky’s worse nature knows how to exploit the streets; his better nature is confounded by them.

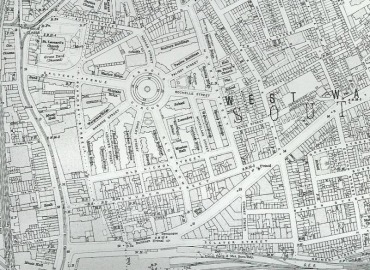

The 30 or so streets, courts and alleys of the real slum had been built on a tiny scale on a grid system; most of the Nichol had been thrown up speculatively at the turn of the nineteenth century, although there were some survivors of the original wave of development in the late 17th century. These latter dwellings were holding up better than the dross that was built circa 1800, with its sagging walls, non-existent foundations, treacherous ceilings and pervasive damp. By the late 1880s, there were no maps that could account for the Nichol’s illegal sprouting of sheds, workshops and stables – slung up without parish surveyors’ say-so in courts, yards and any remaining free space. The last Ordnance Survey had been undertaken in the early 1870s, and with no cartographers interested or motivated enough to chart this parallel world, the Nichol had certain routes through it that were known only to some of its residents.

The Perrotts’ room overlooks Jago Court, a fictionalisation of the Nichol’s Orange Court – ‘the inner hell of this awful place’, as Morrison described the latter, in a defensive interview with the Daily News a year after the novel’s publication. Orange Court comprised broken-down two-and three-storey houses clustered around a yard that was accessible only through a narrow tunnel that passed beneath the first storey of a house fronting Old Nichol Street. The court appeared to the casual observer to be a cul-de-sac; but the passageways of some of the Orange Court houses gave access on to other streets, and once a suspected thief had dashed into the court, police officers knew that they were vulnerable: in one locally notorious incident, a fire grate was hurled down on to the head of a policeman as he emerged from the tunnel into Orange Court (Morrison included this tale in his novel). Orange Court was the site of bare-knuckle prize fights and illegal street-gambling, such as Pitch & Toss. When the court was torn down in 1888 for the building of Reverend Arthur Osborne Jay’s Holy Trinity Church, a tangle of illegal brick sewers and a leaking brick cesspit were found beneath its flag stones.

The reports made by the parish vestry’s medical officer concerning conditions at Orange Court (as well as the other most foetid examples of the Nichol’s physical fabric) form a catalogue of perfectly commonplace nastiness. In Morrison’s version, the squalor is given an infernal, Hieronymus Bosch cast. The Jago on a summer midnight has a ‘coppery glare’ in the glow of a nearby warehouse fire; it is hot, and the houses are verminous, and so ‘contorted forms… writhen and gasping’ are attempting to sleep out on the pavement under ‘a lurid sky’. Here in ‘the blackest pit in London… slinking forms, as of great rats’ pass doorways that are ‘a row of black holes, foul and forbidding’. The Jagoites are described as ‘swarming’ and ‘teeming’, and are frequently referred to as rats; even little Dicky is a ‘ratling’. Part of the reason for this fantasticalisation of a dully awful place is the influence of Oliver Twist upon A Child of the Jago. Morrison never acknowledged Dickens’s 1837 masterpiece as an inspiration, though a number of contemporary critics picked out the parallels in their reviews. In both tales, a rather fetching boy falls under the sway of a master-thief and corrupter of youth; is rescued and falls again because of his wicked associates and a past he can’t seem to shake off. Morrison angrily denied that Aaron Weech was intended to be a Jewish fence and suborner of lost boys; and indeed, Weech has none of the diabolical power – and allure – of Dickens’s villain (Weech also has more than a touch of Bleak House’s Mr Chadband about him, and touches of Uriah Heep and Bleak House’s Krook). The passages concerning Josh’s mental state while on trial and going to the gallows are copies of those that describe Fagin’s trial and death-cell experience; and after the murder of Weech, Josh clambers up on to a rooftop and gazes down at the crowd, Bill Sikes-style. Dicky is entrapped by the dark, daedalian streets of the Jago in much the same way that Oliver’s descent into Saffron Hill and Fagin’s hideout near Field Lane (towards the end of chapter 8 of Oliver Twist) appears to be a slow physical and spiritual strangulation.

In its old-fashioned melodramatic notes, A Child of the Jago is atypical of Morrison’s work. Either side of its publication, Morrison enjoyed success within the detective/mystery genre (with his Martin Hewitt Investigates series) and with historical fiction with a mystery flavour (The Hole in the Wall; and Cunning Murrell); he had also attempted supernatural tales – The Shadows Around Us was published in 1891. But his reputation within literary circles was established by his short stories of ordinary poverty, most notably the collection Tales of Mean Streets, published in 1894. In such pieces, Morrison was a new voice within the slum fiction sub-genre; it was he who brought into focus the monotony and mediocrity of perfectly respectable poverty. The ‘mean’ in Mean Streets referred to the littleness, the lack of aspiration, the lifelessness of hundreds of thousands of upper-working-class East London lives. These tales had none of the hopefulness of Walter Besant’s working-class romances, where redemption can come from education and gradual cultural ‘improvement’; and there is none of George Gissing’s emphasis on the struggling, ambitious hero being slowly crushed by quotidian metropolitan awfulness.

So A Child of the Jago is an oddity within his oeuvre. Writing in the late 1960s, Morrison scholar PJ Keating stated that Morrison’s horror and loathing of the Jagoites was probably attributable to some personal source, and that it was this, Keating believed, that ‘raises the novel so far above his usual output’. Morrison remains a rather mysterious figure. Interviewers failed to winkle much background information from him; and, as she had been instructed, Morrison’s wife, Elizabeth, burnt all his private papers upon his death, in 1945. Recent, diligent scholarship has failed to put much flesh on the bare bones of his biography.

He was born in John Street, Poplar (today’s Grundy and Rigden streets), on 1 November 1863, in respectable poverty. His father was an engine fitter who died (after three years with tuberculosis) when Morrison was eight; his mother, with three children to support, then opened a small haberdashery shop in John Street. At fifteen, Morrison started as a clerk in the London School Board’s architects’ department, and subsequently worked as a clerk at the Beaumont Trust, which administered the People’s Palace, and then became a sub-editor on The Palace Journal, in 1889, where he impressed Walter Besant. He began to write short stories for the Journal and upon leaving his full-time post in 1890, contributed poems about bicycling (his craze of the time) and short stories on a number of themes to various publications, most significantly to the Strand magazine (the journal that nurtured so many writers, not least Arthur Conan Doyle) and to WE Henley’s National Observer (Henley was also at that time encouraging the young Rudyard Kipling). Tales of Mean Streets was a big success for Morrison, and he was able to move from lodgings in the Strand to rural Chingford, and by 1896 was living in some comfort in Loughton. It was here he invited some of the men of the Old Nichol so that he could observe their accent and demeanour: ‘Sometimes I had the people themselves down here to my house in Loughton. One of my chief characters, a fellow as hard as nails… came several times and told me gruesome stories and how the thieves made a sanctuary of Orange Court.’ This was the chap who had dropped the fire grate on a copper’s head.

During the 1890s, Morrison began collecting Japanese and Chinese prints, and in 1913, he stopped writing to devote himself to the study of, and dealing in, Oriental artworks. It was art, rather than literature, that brought Morrison both social respect and financial security. His upward trajectory can be traced in his moves to a house in High Beech, near Epping, then to a mansion flat in Cavendish Square, and finally, in 1930, to High Barn, Chalfont St Peter, Buckinghamshire. His only child, Guy, died of malaria in 1921.

The sketchiest of biographical material appeared in his lifetime, and the 1904 Dictionary of English Authors described Morrison as born in Kent and educated at private schools; his father was now an ‘engineer’, not an ‘engine fitter’. Can we surmise that this upgrading of his past was evidence of how Morrison felt about poverty? Was shame part of the creative impulse behind the arch, sneering hostility to the Jago and all who lived in it? It is tempting to view A Child of the Jago as a record of a clever, ambitious young man putting a lot of distance between himself and the humble Poplar origins that had balanced Morrison precariously on the edge of Jagoism: for all his claims that Jagoism was an inherited taint, the novel’s plot reveals instead the fluidity between respectable indigence and membership of the ‘lowest class, vicious, semi-criminal’ (Charles Booth’s (in)famous 1889 description of the outcast poor). Hannah Perrott, after all, was born respectable but is seen slowly sinking into Jagoism; daft, squalid but kind prostitute Pigeony Poll gets redeemed at the end of the novel through marriage to Kiddo Cook, a criminal costermonger who has decided to go straight, and prospers.

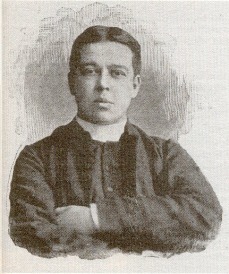

Personal history aside, there is another factor that could account for Morrison’s bleak portrait of the Nichol. The novel was, in a sense, commissioned. In 1894, Reverend Arthur Osborne Jay, vicar of Holy Trinity Shoreditch, in Old Nichol Street, had written to congratulate Morrison on Tales of Mean Streets. If, however, Morrison wanted to write about a wholly different type of East End poverty, Jay would be happy to introduce him to the people of his own parish. This invitation was accepted, and in 1895, Morrison began to visit the Nichol daily. Why did Morrison call the Nichol ‘the Jago’? As historian David Rich has pointed out: because it’s where Jay goes. Father Sturt, the hero of the book, is Jay.

Jay had been the incumbent of Holy Trinity since December 1886; in 1891 he had published an account of his pastoral work in the Nichol entitled Life In Darkest London, A Hint to General Booth, which was partly a manifesto for the type of slow, steady parochial relief work that Jay believed in; partly a plea for funds so that Jay’s pastoral work could increase; and partly a bashing of William Booth’s Salvation Army, whose success at fund-raising appeared to be diverting charitable donations from the Church of England’s poverty relief programmes. In 1893, Jay published a second book, The Social Problem: Its Possible Solution, in which he retailed further tales of Nichol iniquity, in among another plea for funds; and here he also introduced a new eugenicist note. Among his flock, Jay wrote, were a number who ‘by inherited defects and taints of blood, by mental, physical and moral peculiarities, by surroundings and training and circumstances, have no fair chance of being anything but bad. We do not need statistics to prove this. “I should like to turn honest,” said a friend of mine to me one day. We were in the street, and I lifted his hat off. “Let me look at your head.” He burst out laughing, thinking it was a joke. To me it was none at all. I am no phrenologist, but anyone can tell what that sad, sloping forehead, those shifty eyes, those heavy jaws mean… We have with us a large, miserable and costly class: by our own folly they increase daily…’.

Jay’s third book, A Story of Shoreditch, appeared shortly before A Child of the Jago was published, and the crossover between the two is notable, both in the use of specific Nichol incidents and the bleak despair at the notion of ineradicable, biologically transmitted criminality and indigence. The parallels were not lost on the unsigned reviewer of Morrison’s novel for the St James’s Gazette. In this piece, ‘How Realistic Fiction is Written: The Origin of A Child of the Jago’, which appeared in the Gazette’s 2 December 1896 edition, the critic described A Child of the Jago as ‘an illuminated version’ of Jay’s Life in Darkest London’; where Jay’s account had been ‘cold and colourless’, the reviewer stated, Morrison had brought to the same scenes ‘warmth and vitality’. In the following week’s edition, Jay angrily denied there had been any interference from him in Morrison’s work, stating that his own books and Morrison’s novel were dissimilar.

At about the same time, Arthur Morrison demanded that HD Traill ‘trot out his experts’, if Traill wanted to prove that the novel was a distortion. Perhaps to Morrison’s surprise, Traill did exactly that. He found people who knew the Nichol very well who were willing to go on record to refute Morrison’s vision. Woodland Erleback had been a manager at the Nichol Street Board School for 30 years and stated that ‘the district, though bad enough, was not even 30 years ago so hopelessly bad and vile as the book paints it. The characters portrayed may have had their originals but they were the exception and not the rule’. JF Barnard, meanwhile, told Traill that he had carried cash to and from the Nichol Street Penny Bank since 1874 and had never once been robbed. The textiles firm of Vavasseur, Coleman and Carter, whose warehouse in New Nichol Street stored bolts of valuable silk, had never had a break-in. Two more Board School managers; a pastor at the non-denominational London City Mission; a Poor Law guardian who had been resident in the Nichol for several years, and two women who ran local Mothers’ Meetings came forward to Traill to defend the people of the Nichol.

Just over a year later, Robert Allinson, of the London City Mission in Old Nichol Street told one of Charles Booth’s Life & Labour researchers that the Nichol had been ‘painted much too dark, simply on the word of one man [Jay]’. Allinson said that the area had been ‘no worse than several other poor places. He knew it well and visited from house to house, going from “cellar to ceiling”. He admits it was bad, but objected to the district being gibbeted as the bad spot.’

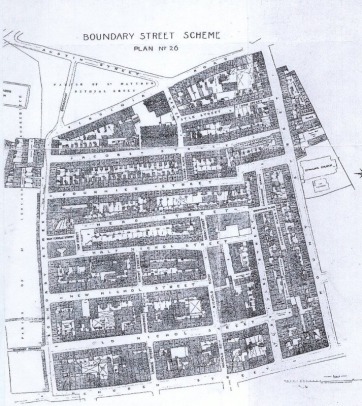

Morrison said that he knew East London as no other writer did; he pointed out that he had spent 18 months visiting the Nichol before starting to write A Child of the Jago, in April 1896. At the time of its publication, in the November of that year, a number of reviewers wondered why Morrison had decided to write about a spot that, rather famously, no longer existed: in 1891, the London County Council (LCC) had decided to demolish the Nichol in its entirety for the provision of new model dwellings for the working classes. But what the commentators of the day hadn’t grasped was that by the time Father Jay had invited Morrison into the Nichol to study its inhabitants, one-fifth of its population had already been evicted for the demolitions; during Morrison’s 18 months of research in the slum, the final closure notices were being served to locals, and ne’er do wells from across the capital came to squat in the vacated properties, living rent free and in the hope that the LCC would have to pay them weekly-tenant compensation.

In January 1893 – 20 months before Morrison turned up in the Nichol – the local newspaper, The Eastern Argus, proclaimed the area ‘The Land of Desolation’, declaring, ‘Half the houses are now closed by the orders of the County Council, and the dark and deserted alleys afford a likely sanctuary to the burglars and garroters of who we hear so much lately.’ Mounted policemen now patrolled the streets of the Nichol, and there were reports of working men being dragged off the Bethnal Green Road and being robbed. But this was not being done by the people of the Nichol; they had been sent elsewhere by the time of Morrison’s field trips – October 1894 to April 1896.

Morrison’s had not been an eyewitness account but a faithful regurgitation of tales told to him by Father Jay, some of which, what’s more, had come to Jay at second hand. ‘Typical facts were all I wanted,’ Morrison had protested to his critics. Instead, he had retold atypical, and legendary, Nichol events, from which he constructed his fairyland of horror.

A disappeared neighbourhood

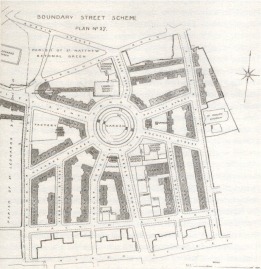

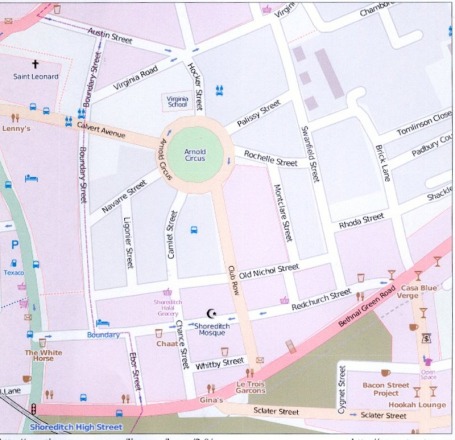

The LCC’s Boundary Street Estate was a complete reconstruction of the area and today, little remains of the Nichol.

The LCC did not demolish the two Board Schools, built in the 1870s – they stand at the west and south-east edges of Arnold Circus. Meanwhile, Boundary Street (Edge Lane in Morrison’s novel) still features a few original buildings at its southern end, on the western side; and ‘The Posties’ – the narrow alleyway that connected the Nichol to Shoreditch High Street – is still there, although the Posties themselves have been upgraded (local legend had it that the posts had been made from upturned cannons from a ship in Nelson’s fleet).

The south side of Old Nichol Street did not become part of the LCC estate; similarly, Redchurch Street (formerly Church Street/Morrison’s Meakin Street) and the southernmost part of Club Row feature buildings that Morrison would have known. Ebor Street, Chance Street and Turville Street were not part of the LCC reconfiguration and the former two retain their cobbles, while the latter has some early 19th-century buildings.

Orange Court became the site of Holy Trinity, Shoreditch, which was itself destroyed by a direct hit in May 1941; today, a children’s playground is on the spot. Another local rumour has it that the foundations of Father Jay’s edifice lie beneath.

Today, the Estate is a largely harmonious home to three communities: traditional white Bethnal Greeners; families of Bangladeshi origin; and young professional incomers, some connected with the art scene (Morrison’s Meakin Street is today packed with tiny galleries). The Friends of Arnold Circus and the Tenants & Residents Association work hard to maintain and make full use of the communal spaces of the magnificent estate – not least the striking raised garden with bandstand atop which lies at its heart – and to keep alive the fascinating social history of this spot: many have read A Child of the Jago, and some of them actually believe it.

References and Further Reading

On the Nichol:

– The Blackest Streets: The Life and Death of A Victorian Slum by Sarah Wise, 2008

– East End Underworld: Chapters in the Life of Arthur Harding by Raphael Samuel, 1981.

– Life in Darkest London , 1891; The Social Problem, 1893; A Story of Shoreditch, 1896, by Arthur Osborne Jay.

– Recollections of a School Attendance Officer by John Reeves, circa 1915

– Later Leaves: Being Further Reminiscences of Montagu Williams, QC 1891

On Arthur Morrison:

– The Working Classes in Victorian Fiction by P.J. Keating, 1971

– ‘What is a Realist’ by Arthur Morrison in New Review, vol.16, March 1897

– The New Fiction and Other Essays on Literary Subjects by H.D. (Henry Duff) Traill, 1897

– ‘A Slum Novel’ by H.G. Wells, review in The Saturday Review, 28 November 1896

– ‘The Slum Movement in Fiction’, in Stones from a Glass House by Janet Findlater, 1904

– ‘ A Novel of the Lowest Life’ by Harold Boulton, in The British Review of Politics, Economics, Literature Science and Art, 9 January 1897

Slum Fiction:

– Tales of Mean Streets by Arthur Morrison , 1894.

– ‘The Record of Badalia Herodsfoot’ by Rudyard Kipling, 1890.

– Captain Lobe by John Law (ie Margaret Harkness), 1889; republished in 1891 as In Darkest London

– The Nether World , 1889; Demos, 1888; In the Year of Jubilee, 1887; George Gissing.

– Liza of Lambeth by Somerset Maugham, 1897.

– The Hooligan Nights by Clarence Rook, 1899.

– All Sorts and Conditions of Men, 1882; Children of Gibeon, 1886, by Walter Besant.

– No 5 John Street by Richard Whiteing, 1899.

– A Princess of the Gutter by LT Meade, 1895.

– King Dido by Alexander Baron, 1969 (historical slum fiction)

All rights to the text remain with the author.

Thanks to Igor Clark for permission to use his photo of Boundary Passage.