Charles R. Larson

Though Kamala Markandaya (1924-2004) spent most of her life as a writer in England, her eleven novels (beginning with Nectar in a Sieve, 1954), were set almost exclusively in India, typically depicting traditional life and values and the ways they came into conflict with modernity. Her seventh novel, The Nowhere Man (1972), was the only story with an English setting, though there are flashbacks to India. It was also her favorite — of all her works — no doubt because the story was something she had observed frequently in her adopted country: racism.

By addressing that issue frontally, she paved the way for novelists from the Indian subcontinent (especially Salman Rushdie and Nadeem Aslam) who would subsequently take the issue to more upsetting levels of confrontation. My assumption is that Markandaya must have been apprehensive of the response the novel would have with British readers, pushing them out of their comfort zones.

As the story begins, Srinivas, an elderly Brahmin, has lived most of his adult life — nearly thirty years — in London, outliving his wife and one of his sons. It’s 1968, and both of his sons fought for the British in the war, but only one returned. Ironically, the surviving son also lives in London but Srinivas was never close to him. Communication between the two is virtually non-existent.

As the story begins, Srinivas, an elderly Brahmin, has lived most of his adult life — nearly thirty years — in London, outliving his wife and one of his sons. It’s 1968, and both of his sons fought for the British in the war, but only one returned. Ironically, the surviving son also lives in London but Srinivas was never close to him. Communication between the two is virtually non-existent.

Srinivas rattles around in the attic of the house he has lived in for years, since he’s rented out the first two floors. Not many years ago when his wife died, he was about to be arrested for throwing her ashes into the Thames. “The river’s not the place for rubbish,” a policeman tells him. But Srinivas’ response — “It was not rubbish… It was my wife.” — brings a moment of compassion from the man, the last time that anyone will treat him decently.

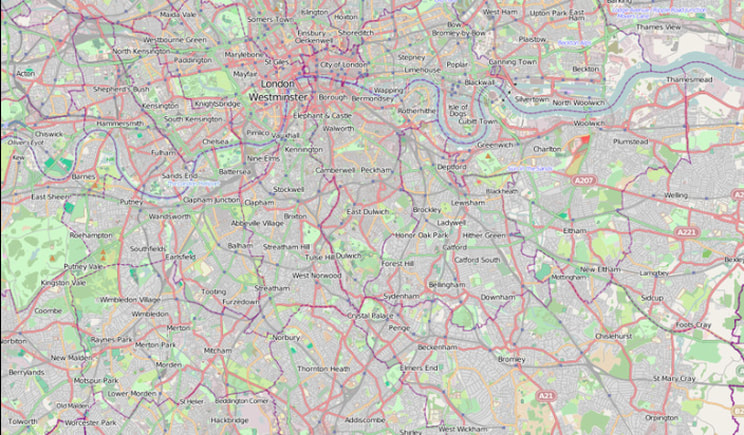

Britain is changing color because of all the immigrants who have arrived from its colonies. Whole neighborhoods suddenly look different and — as has happened so many times in other Western countries — those at the bottom are threatened, fearing that their jobs will disappear (to the much harder-working immigrants) and that these new foreigners will soon get rich. Observing the incipient hostility, Srinivas briefly considers returning to India but finally concludes, “He had no notion of where to go to in India, or what to do when he got there.” He knows that the country has changed. He also thinks to himself, “This is my country now.” In some ways he has become more English than the English around him. Much later he will realize, “If he left he had nowhere to go.” He’s a nowhere man.

So they bought a house, a gaunt old building in South London. Which was not difficult to do in that nervous year before the Second World War, when there were more sellers than buyers. Vasantha selected it, basing her requirements with an eye to the future when her sons, at this point aged thirteen and fourteen, would be grown up and married. Then the loving mother-in-law would allocate one upper floor to each son and wife, and the ground floor reserved for themselves, ageing parents who would be past climbing the stairs. All this despite certain distinct possibilities, which she accepted, and having done so sailed serenely past the rubble. What had to be, would be: meanwhile one had to plan. …

So the house was acquired, under whose rafters Srinivas now sat. A house with basement and attic which they had not wanted, which were immutably linked with two-storey structures. … When the deed was done, and No. 5 Ashcroft Avenue was theirs and the building society’s, and they sat among their cases in the front reception whose bay was hung with soot-heavy trusses of tattered ecru, Vasantha said with pride: ‘At last we have achieved something. A place of our own, where we can live according to our lights although in alien surroundings: and our children after us, and after them theirs.’

If Kamala Markandaya were alive today she would no doubt be horrified by the millions of refugees throughout the world who, for one reason or another, have nowhere to go. They’re often stateless, caught in political limbo, the result of overthrown governments, wars, famine, and — most recently — climate change. How ironic, then, that Srinivas is not the product of any of these cleavages but simple homegrown racism. Hard to determine which is worse.

As incidents of British racism impact upon his life, Srinivas remembers earlier racial incidents from his past, when he was still a student, and experienced similar slights under British colonialism. He fled India as a young man because of a number of humiliations he had experienced at the university because of that racism. Thus, there’s a kind of continuum of discrimination from the same people — first in his own country and later in theirs.

How surprising (or perhaps not) that the worst acts of violence inflicted on him are from the loutish young man who lives in the house next door. He’s unemployed, hardly more than a punk, though married with several children and living under the roof with his mother, who considers Srinivas one of her friends. Yet Srinivas — an old man and clearly no threat to anyone — becomes the focal point of his racism because Fred Fletcher can’t take his eye off his neighbor, turning his life into hell. But the hellish ending of Markandaya’s novel you will need to discover for yourself — along with its many rewards as a compelling narrative.

And now a confession. I knew Kamala Markandaya (an absolutely elegant woman) for many years. I read The Nowhere Man the year after it was first published. I was instrumental in convincing Penguin/India to reprint all of the novels of this major Indian writer in a uniform edition.

And now a confession. I knew Kamala Markandaya (an absolutely elegant woman) for many years. I read The Nowhere Man the year after it was first published. I was instrumental in convincing Penguin/India to reprint all of the novels of this major Indian writer in a uniform edition.

A few months ago when The Nowhere Man was released, I knew it was time to read this major daring a second time. I was not disappointed and remain hopeful that the Markandaya volumes — thus far only for sale in India — will be available to readers throughout the rest of the English-speaking world.

Charles R. Larson is Emeritus Professor of Literature at American University in Washington, D.C. Email: clarson@american.edu. This article was first posted in CounterPunch in February 2013 with the title ‘Engulfed in British Prejudice’. London Fictions is grateful to both Professor Larson and CounterPunch for permission to repost this writing.

All rights to the text remain with the author.