Sam Wiseman

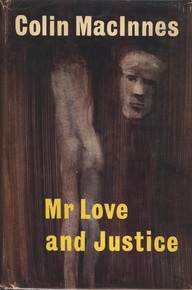

The British-Australian journalist and author Colin MacInnes (1914–1976) is best known for his novel Absolute Beginners (1959), with its portrayal of nascent teenage culture and racial tensions in London during the summer of 1958. That work forms the centrepiece of MacInnes’ ‘London trilogy’: it joins City of Spades (1957) and Mr Love and Justice (1960) in an attempt to provide a kaleidoscopic view of the capital in this tumultuous period. Generational, cultural and racial conflicts play out against the backdrop of a London that is by turns drab, seedy, modern, bomb-scarred, volatile and vibrant; in all three novels, a lukewarm attitude towards the ideals and institutions of the postwar welfare state runs alongside a fascination with the vice, criminality and transgression that thrive in this disorderly and rapidly-changing world.

It is these latter themes with which MacInnes principally concerns himself in Mr Love and Justice, a short novel that traces the fortunes of its two protagonists in alternating sections, using a third-person narrator often closely aligned with one or the other.

While MacInnes’ journalistic background is evident in the novel’s strong sense of place and social issues, this is combined with his predilection for strangely shallow, archetypal characterisation: the links between his protagonists’ names and occupations (Edward Justice is a corrupt police officer in the vice squad, while Frankie Love is a sailor-turned-pimp) lend the novel an air of cartoonish unreality, despite its grittiness. The private and public lives of both men increasingly mirror one another, as the novel moves towards a conclusion that sees their activities converge.

In his intertwining of these two figures’ lives, MacInnes suggests parallels between those who make a living on both sides of the law: both men are venal, prone to violence, prejudiced, misanthropic and cynical. In presenting the reader with two unlikeable protagonists, the novel takes a high-risk narrative approach. We see events through their eyes—particularly in the frequent passages of free indirect discourse, which closely align the narrator with the protagonist in question—but do not warm to them. While this is an effective way of highlighting the cruelty and nihilism of the worlds in which these men move, the novel’s strongest feature is its detailed and evocative descriptions of several areas of London. In such passages, a more poetical and contemplative narrative voice emerges, seemingly not aligned with either protagonist.

Although the novel ranges across the city, MacInnes seems most fascinated by Kilburn and Stepney, which are in many ways opposed to one another within the narrative. The former is presented as a region of ‘straight-laced seediness […] behind which lurks something dubious and occasionally horrifying […] the particular English mixture of lunacy and violence flourishing inside persons, and a décor, of impeccable lower-middle-class sedateness’ .In contrast to this predominantly white, petty bourgeois, curtain-twitching world, MacInnes sets Stepney, where due to ‘the markets, seamen, and Commonwealth minorities […] you can eat and drink, as well as other things, at any hour you choose to’. The area is associated with transience, diversity and vibrancy; like many of its inhabitants, newly arrived in Britain, it is ‘thoroughly confused about itself’ and its identity.

To some extent, the novel’s two protagonists are associated with these two areas. Edward is ‘a worshipper of the conventional’, yet simultaneously ‘a lover of stress and strain and conflict, wherein he himself may operate behind that outward, visible order he admires’. Kilburn’s sense of perversity hidden behind a façade of respectability appeals to this dual nature. The indeterminate identity of Stepney, on the other hand, reflects Frankie’s sense of self as a land-bound merchant seaman, who turns to pimping because no ship work is available. This is established in the novel’s opening lines: ‘Frankie Love came from the sea, and was greatly ill at ease elsewhere. When on land he was harassed and didn’t fit in at all’. Frankie’s sense of alienation and his resentment at being bound to ‘the landsman’s meaningless caprices’ give him common ground with the immigrant populations of Stepney, and in the novel’s opening chapter he is bought lunch by a south Asian man in a ‘Pakistani café with a smell of stale spices, a juke-box, a broken fruit-machine, and several English girls’. MacInnes does not gloss over the endemic racism of British culture in the period, and we are later told that ‘Frankie, like most proletarian Europeans, despised Asiatics to such a degree that you could hardly even call it contempt’ (69); but there is nonetheless an uneasy coexistence that develops among Stepney’s diverse inhabitants in the novel, reflecting their collective marginalisation from mainstream society.

Within these contrasting districts, MacInnes explores the evolving dynamics of subterranean or marginal worlds with London’s institutional buildings and spaces. The repressed sexual deviance of the suburban middle class, for example, finds its expression in that archetypal site of homosexual transgression, the public toilet. The progress of Edward’s career is indicated by his growing confidence in exacting bribes from men such as the besuited office worker who makes ‘a fatal gesture’ to him at a urinal. A gay man himself, MacInnes appreciates the ironic contrast between the ‘ludicrous solemnity’ of London’s Victorian and Edwardian public toilets, and their function as cruising spots. He uses the encounter to shift into contemplative narrative mode, in a passage that explores the ideologies embedded within the ‘larva-hued earthenware, the huge brass pipes’ and ‘the great slate walls dividing the compartments, […] all built on an Egyptian scale’. The ‘municipal Pharaohs who designed these places’ gave them a paradoxical mixture of intimate ritualism and repression, suggesting ‘physical communion […] a sort of lay confessional’, and at the same time, ‘a really sensational and alarming fear and hatred of the flesh’. Few examples survive today, the best probably being those at South End Green (built 1897), used as a cruising spot by MacInnes’ contemporary, Joe Orton.

For MacInnes, the design of such places somehow embodies the hypocrisy, pomposity and repression that characterise the lower-middle-class strata found in neighbourhoods like Kilburn. These are areas in which the ‘countless anonymous 1950 blocks’ built by the postwar Labour government have had little impact, failing ‘to transform London from what it still after years of bombing and re-building essentially remains—a late-Victorian city’. While it is to one of these new developments that Edward and his girlfriend relocate, such projects have as yet failed to influence either the character of the district or the mindset of its inhabitants. For many of these people, MacInnes suggests, the ‘New Jerusalem’ of the Attlee government remains at best a vague abstraction, at worst a threat to their social position. As Alan Sinfield (1989) has shown, middle-class responses to the ‘postwar settlement’ were complex and often ambivalent, shot through with status insecurity and class snobbery.

Much of the reason Edward finds Kilburn ‘reassuring’ is the relative lack of ‘people loitering in streets, dressing extravagantly, speaking with exotic accents, being strange, weak, eccentric, or simply any rare minority’ —a litany of qualities that captures Stepney as MacInnes presents it. Here too, the contrast of modern housing blocks with older residential accommodation is acknowledged, but in contrast to Kilburn, the pre-1945 housing consists of ‘incredible slums’, which the narrator speculates ‘are preserved there by authority to demonstrate the contrast of before-and-after’. MacInnes does not anticipate the associations of crime and social decay that will attach to housing estates following the rise of Thatcherism, or the gentrification of former slums in the same period. As Patrick Wright explains, these Georgian buildings were ‘being used, right up into the seventies, to press the case for slum clearance and redevelopment’; yet by the Eighties, the ‘blitzed-out imagery of the slum interior was being augmented’ and used to sell a romanticised version of the past.

Central to the stories both Wright and MacInnes tell is Spitalfields vegetable market (ousted by gentrification in 1991): in Mr Love and Justice, we learn of its ‘vigorous dawn life and odour of veg, fruit, and flower—like blended essences of the citizens’ duties, delights, and fantasies’. The smells, colours and noise of the market function as a synecdoche for Stepney’s ethnic and cultural diversity, its unpredictability and amorphousness. What ‘remains astonishing, since this is England, about this delightful state of affairs, is that no one has yet managed to suppress it’, says the narrator, intuitively grasping the inevitably transient qualities of the area.

Whether it surveys the immigrant communities of Stepney or the lower-middle classes of Kilburn, MacInnes’ narrative feels alternately indifferent to, or sceptical of, the egalitarian ideals embodied in the new housing estates. Mr Love and Justice celebrates London as a city which spiritually resists this kind of rationalised planning. Aside from the novel’s closing scene, in which Edward and Frankie ‘form bonds of solitude, and ennui, and suffering’ in the symbolic setting of an NHS hospital, state institutions are presented as ineffective, bureaucratic, corrupt or callous.

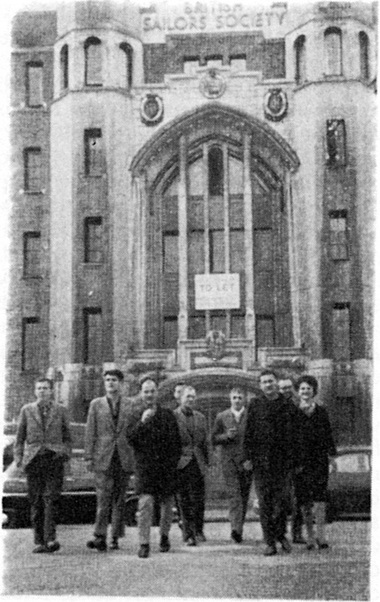

When the novel opens, Frankie is met with incomprehension at the Labour Exchange, and needs an unaffordable bribe to gain work at the Dock Board. Other institutions in the area did provide solace for land-bound sailors at the time: for example, the Sailors’ Mission on Commercial Road (home to ‘nocturnal vice caffs’, as the narrator tells us). This building, today converted to apartments, hosted the Situationist International conference in 1960 (the year of Mr Love and Justice’s publication), and there are connections between the emergent theories of Situationism and the novel’s sense of an ongoing reinvention of public space by Stepney’s migrant communities. Wentworth Street, for example, has ‘real life […] almost unknown elsewhere in London where roads are considered means by which you move from place to place, not places in themselves’. The area’s inhabitants resist the pressure to experience such spaces merely in terms of their capitalist utility, instead reinventing them as places of community or leisure.

MacInnes’ text also anticipates Peter Ackroyd’s psychogeographical detective story Hawksmoor (1985), which similarly alternates between chapters corresponding to figures on either side of the law, and is alert to the ‘macabre, poetic beauty’ that MacInnes identifies in the docklands area; St Anne’s Church, Limehouse, is one of the Nicholas Hawksmoor churches around which Ackroyd’s novel is structured. Stepney, we are told, is an area ‘in transition from various ancient states of being to new ones it is still busy searching for’ (98), and this notion of a place that somehow simultaneously occupies different temporal zones—of the ways in which a district is haunted—is also a key element of Hawksmoor, and of psychogeography more generally.

If Kilburn, in the novel, struggles to escape its late-Victorian atmosphere, Stepney displays a more complex mixture of residual pasts and vibrant presents. The area’s Jewish history is evoked in the description of Old Montague Street, which ‘has still the flavour of a semi-voluntary ghetto’, with ‘its discreet, secretive synagogues’. Cable Street, the site of the East End’s proud rejection of fascism in 1936, is also evoked, but MacInnes focuses upon the latest wave of occupants: ‘castaways from Africa and the Caribbean [who] perform a perpetual, melancholy, wryly humorous ballet of which they are themselves the only audience’. This is an area where these overlapping histories and communities have created a rich cultural palimpsest, and it is unsurprising to be told that ‘only here, in one sense, is London really a capital city at all’; because it is only here that is ‘open for business all night, and for seven days in the week’.The area’s vibrancy is celebrated despite—or because of—the ever-present threat of the City’s ‘gruesome Venetian financial palaces’ which abut onto the area. Stepney’s refusal to maintain a fixed character or identity is mirrored in Frankie’s ambiguous status, as a merchant seaman who learns to navigate the treacherous landscape of London’s criminal underworld without ever fully embracing the landlocked life. Similarly, Kilburn’s ‘respectable wastes […] of self-righteous drabness’ appeal to Edward’s ‘ingrained conservatism,’ his ‘almost desperate love of the conventional’.

Mr Love and Justice acknowledges how the character of a district can change over time due to the forces of capital and migration, but it also emphasises the ways in which areas resist such processes, and the residues of the past that persist. Through his twin protagonists, MacInnes demonstrates that individuals are symbiotically entwined with places through these phenomena, both shaping and shaped by the character of the areas in which they live.

Sam Wiseman received his PhD in English Literature from the University of Glasgow in 2013. His first book, The Reimagining of Place in English Modernism, was published by Clemson University Press in 2015. He is currently undertaking a postdoctoral research project, Locating the Gothic in British Modernity, at the University of Erfurt, Germany.

References and Further Reading

Alan Sinfield (1989). Literature, Politics and Culture in Postwar Britain (Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

Patrick Wright (2009). A Journey Through Ruins: The Last Days of London (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

The photograph of the public toilets on South End Green is posted with the kind permission of Stephen Emms: http://www.kentishtowner.co.uk/2013/10/23/wednesday-picture-south-end-greens-infamous-gents-toilet/