Kate Houlden

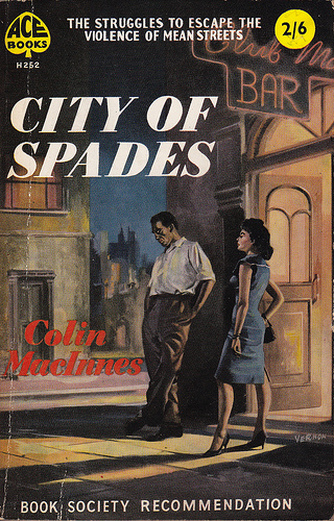

London has been described as the ‘true hero’ of City of Spades and its author, Colin MacInnes, certainly takes us on a whirlwind tour of the city. His London, however, would have been unfamiliar to many at the time, for this novel – published in 1957 and the first of what’s often described as MacInnes’s London Trilogy – focuses on an emergent black culture. It brings vividly to life the pubs and dance halls that many contemporary readers would have considered firmly out of bounds, offering an alternate mapping of this great city.

Two quotations drawn from the book give a sense of the differing perspectives it offers on the changing London of the 1950s, when post-war migration began to have a significant effect on the city’s demographics.

Two quotations drawn from the book give a sense of the differing perspectives it offers on the changing London of the 1950s, when post-war migration began to have a significant effect on the city’s demographics.

‘I want to get to know the various areas if it’s going to be my home’

The first, is spoken by the optimistically named, Johnny Fortune, an African migrant determined to make the most of the city’s charms. His confident belief in his ability to make London ‘my home’ gestures towards the transformative effect that those making the ‘reverse migration’ from the colonies to the imperial centre would have. Johnny wants to stake his claim to the city previously seen only in films and photographs, a city he had been taught to believe would be a site of ‘creation, and riches, and power in the modern world’, where ‘life is bigger, wider, more significant’.

‘Muriel saw her city as a place quite unfamiliar, and wondered what it might do to her’

The second is the voice of his white lover, Muriel, who struggles to make sense of the impact these new arrivals have on her previously staid London life. Her words indicate the confusion of native Londoners as they discover that the city of which they were so confidently in possession is perhaps not quite their own after all. In the case of Muriel and Johnny, this meeting of cultures is less than successful, as he leaves the city in disgrace, having abandoned her and their child. Nevertheless, City of Spades is a riotous chronicle of a London in flux. It evokes geographies, foods, music and cultural forms taken for granted today and confidently paints the picture of a crucial era in the formation of this most multicultural of cities, when the hopes of colonial migrants had yet to be dashed by events like the Notting Hill riots (addressed in MacInnes’s next book, Absolute Beginners).

MacInnes’s story is told through two alternating first-person narrative voices: those of the above-named Johnny and of the English colonial official, Montgomery Pew who, against all the odds, becomes Johnny’s friend. This format gives MacInnes plenty of scope to reveal the thoughts, feelings and confusions shared by Jumble (the English, a derivation of John Bull) and Spade (blacks, as in Ace of Spade) alike. The black migrants, for example, lampoon their reception by the English, laughing at how ‘some kind English gentleman’ invariably asks ‘Don’t you miss the hot weather over here?’ or states ‘I like coloured people myself’. Jumbles, meanwhile, struggle to understand ‘why do they flock here to England?’ – a remark gaining the indignant riposte: ‘Always these white people who ask us why we come here! Do we ever ask you […] why your people came to our country long ago?’

‘If this book [City of Spades] had a soundtrack, it would be provided by the first two London Is the Place for Me anthologies’

The novel traverses huge swathes of London: from Maida Vale to Brixton, Regent’s Park to Greenwich and the East End to Marble Arch, MacInnes’s characters are emphatically on the move. Its contents alone provide a heady sense of this roving tendency, with lists of venues and locations predominating and chapter titles such as ‘Pew and Fortune Go Back West’ or ‘A Pilgrimage to Maida Vale’. Johnny begins his London sojourn at the Colonial Department hostel in SW1 (near Victoria and Green Park), a location of which he does not approve, likening it to a ‘mission school’ back home. Modelled on the real-life hostels set up to deal with the migrant influx in the 1950s, this site retains the sober and imperious stamp of colonial administration.

Johnny escapes it to move in to his friend, Hamilton’s home in Holloway, owned by another Nigerian. Unlike many of the run-down migrant dwellings populating the novel, this proves ‘a most delightful residence: with carpets and divans, and shaded lamps and a big radiogram’, a description signalling the private and domestic needs of the novel’s black characters and one that stands in contrast to the nomadic and unsettled elements of many of their lives. As Johnny’s finances spiral out of control, he is forced to head East, a ‘bad, bad sign’ according to Caribbean calypsonian, Mr. Lord Alexander, who informs Montgomery, ‘there’s East End Spades and West End Spades. West End are perhaps wickeder, but more prosperous and reliable’.

Johnny, it turns out, is now living on ‘Immigration Road’ an ‘East End thoroughfare’ running directly to Limehouse, suggesting that MacInnes was, in fact, using the real-life Commercial Road as his template. Today, this street is book ended by the modish Whitechapel Art Gallery in the West and the industrial units and new developments of the docks in the East, demonstrating the extent of change that has swept through London’s now fashionable East End in the last two decades. Finally, as Johnny’s luck runs out, he finds his ultimate home in the metropolis in the bleak environs of Brixton prison.

As Johnny traverses the city, numerous, often surprising insights are given into his view of its pleasures and disappointments. His claim, for example, that ‘England is quite wasted’ because ‘the lands of opportunity are America, and China, and Africa’ is demonstrated by the subsequent comparisons made between London and his home city, of Lagos. When Johnny is informed that London landladies may not welcome black tenants, he responds ‘in Lagos, anyone will let you a room if you have good manners, and the necessary loot’. Similarly, the squalor of Immigration Road is compared to the fact that ‘though back home we have our ruined streets, they haven’t the scraped grimness of this East End thoroughfare’. Johnny’s status in his home country is also made clear. He regally notes how ‘I do hate poor rooms’, while on first appearances, London ‘was a bad disappointment: so small, poky dirty, not magnificent!’ Here then, the waning power of the imperial centre is evoked through the city’s drab and war-damaged streets and dwellings.

The novel makes abundantly clear, however, that London is also being made over to meet the needs of its new, African, Asian, Caribbean and African-American inhabitants; a ‘Spade city’ is springing up within its existing topographies. As Montgomery phrases it when he invites his friend, Theodora to join he and Johnny on an evening jaunt: ‘would you like to come into a world where you’ve never set foot before, even though it’s […] underneath your nose?’ Accordingly, MacInnes introduces his readers to the various locations around which Spade life is organised, specifically the trio of venues: the Moorhen pub, the Cosmopolitan dance hall and the Moonbeam basement club.

The novel makes abundantly clear, however, that London is also being made over to meet the needs of its new, African, Asian, Caribbean and African-American inhabitants; a ‘Spade city’ is springing up within its existing topographies. As Montgomery phrases it when he invites his friend, Theodora to join he and Johnny on an evening jaunt: ‘would you like to come into a world where you’ve never set foot before, even though it’s […] underneath your nose?’ Accordingly, MacInnes introduces his readers to the various locations around which Spade life is organised, specifically the trio of venues: the Moorhen pub, the Cosmopolitan dance hall and the Moonbeam basement club.

The first of these, the Moorhen, ‘near the complex of North London railway termini’ is not an auspicious welcome into this underground world. Described as ‘dispirited baroque’ outside, it is ‘half invisible in the gloom’ and thronged about with ‘Negroes of equivocal appearance’, so that Montgomery’s taxi driver warns him ‘better keep your hands on your pockets, Guv’. Inside, however, an alternate domain opens up, as we are told: ‘dark skins outnumbered white by something like twenty to one, there was a prodigious bubble and clatter of sound, and what is rare in purely English gatherings – a constant movement of person to person and group to group’. Echoing the activity so characteristic of the novel as a whole, this passage conveys Pew’s wonder at the strangeness of entering a hitherto unknown community. It also reflects MacInnes’s own pleasure at being introduced to similar locations himself in the London of the 1950s.

The Moorhen, for example, is his version of the Roebuck, a long since closed establishment on Tottenham Court Road, while in his factual writings, MacInnes describes Notting Hill in similar terms, as an area where Spades ‘have organised their own underground of life and of such joy as may be snatched from an unwelcoming mother country’. As the critic, Francis Wyndham therefore observes, what MacInnes is really writing about in this novel ‘is the effect on himself of the new London and its inhabitants’.

MacInnes’s fictional counterpart, Montgomery Pew meets a colourful (if occasionally two-dimensional) palate of characters in the Moorhen, from dope-peddlers and hustlers to criminals and tribal chiefs, before being led across the road to the next venue in this heterodox mapping of the city: the Cosmopolitan dance hall. This raucous, overflowing venue sees ‘Africans, West Indians, and coloured G.I.s all boxed up together’. An unlicensed premises ripe with the heady smell of marijuana, the Cosmopolitan has a live band, which, even though ‘only Jumble imitation of our style’ is, according to Johnny, ‘quite a hep combination, with some feel of the beat’. On the dance floor ‘our boys were acting cool and crazy, letting their little girls do all the work as they twisted them around’, although ‘to ask for partner, as I saw, all you must do was just walk up and grab’. Such fun is halted, however, when the police raid the establishment, arresting many of the clientele on spurious charges – Johnny and Montgomery included – in what MacInnes suggests is an all too familiar occurrence. This, too, is borne out in accounts of the time, for the Cosmopolitan is a renamed version of the Paramount dance hall, which was situated on Tottenham Court Road. One-time punter, the Jamaican, Enrico Stennett recalls that, while many dancehalls had restrictive entry policies designed to keep black customers out, in the case of the Paramount, ‘the racism was operated by the Police’, who would gather outside the club each week ‘waiting for the dance to finish and looking for trouble’. As Stennett describes it:

Their [the police’s] fun was to wait until a black man came out arm in arm with a beautiful girl, and then they would deliberately stick their foot out tripping up either the woman or the man that was the nearest. This would cause trouble […] and before long many would be arrested on trumped up charges such as breach of the peace, obstruction and assault.

Replaced by the London landmark, Centrepoint in the 1960s, the name (if not the spirit) of this original venue lives on in the exclusive members-only club, Paramount, which today occupies the top three floors of the tower.

The location on which MacInnes’s Moonbeam basement club – ‘which every Spade we met seemed heading for, like night beasts to their water-hold’ – is based is less clear. First coming to it, ‘alive with awnings, naked lights, and throngs of coloured men’, Pew is astounded to discover its presence, observing ‘never had I thought that the bombed out site across the way contained, by night, in its entrails, the Moonbeam club’. A G.I. rendezvous, ‘loaded up with chicks […] some trading, and other voluntary companions’, this basement club, ‘a long low room like the hold of a ship’, contains an orchestra, a small dance floor of jiving couples and a soft-drink bar. Pulsing with ‘throbbing music’ it has, in Pew’s eyes ‘a warm colored fug and stuffiness – sticky, promiscuous and cloying, a hot grass hut in the centre of our town’. Here, the more problematic elements of City of Spades are evident, with Pew making the lazy assumption that the jungle has come to town.

What MacInnes does achieve in this account of the Moonbeam, however, is an early acknowledgement of the differences between various segments of the black community. For it makes clear the tensions between G.I.s, Africans and West Indians, which, he appears to suggest, have much to do with the difficulties of ‘hustling’ a living in the city. In this instance, such tensions culminate in a mass brawl, where insults like ‘calypso-singing slaves’ and ‘my ancestor had the wisdom to leave your jungle country’ are traded. Despite being slightly awkward in its presentation, this scene does form a rebuke to those of MacInnes’s countrymen who showcase their own ignorance by demanding ‘how do you tell which is which among you people?’

At the same time, this vignette is suggestive of one of the difficulties of the book as a whole: the question of how legitimate it is for a white writer to represent a Spade city. On the one hand, MacInnes is clearly able to offer an insider’s view of white racism. From the last white patron of the Moorhen who complains that ‘a year or so ago this was the cosiest little boozer for arf a mile’ to the broader acknowledgement that the Moonbeam will soon ‘be closed by public opinion’, the author does not shy away from revealing the narrow-minded fears and ignorance of his fellow Londoners. He also evidently sanctions the presence of black colonial citizens within the metropolis, with Muriel acknowledging that the majority of Britons ‘just don’t realise that you’re here to stay’. Yet MacInnes’s white characters, particularly Montgomery Pew, also demonstrate a worrying tendency to essentialise, recycling long-standing myths of black musicality, physicality and unreliability. Such thinking, however, as MacInnes himself perhaps also recognised, would only ever change with inter-mixing and co-habitation; the very developments that City of Spades embraces. As John Williams argues:

It has long been fashionable to diss MacInnes as a patronising whitey, and to stress instead the (very real) achievement of the black writers of the period: Selvon, Lamming, Salkey et al. However, this either/or approach strikes me as a particularly depressing manifestation of liberal guilt. For MacInnes is writing about a multiracial world: one that is no more or less owned by the Australian MacInnes than the Trinidadian Selvon.

This useful caution reminds us there is no one voice that should speak for a city as diverse as London. It also offers a nod towards MacInnes’s own origins, for the author in fact, spent much of his youth in Australia, explaining in later life how ‘when I returned to London […] it was partly as a foreigner […] my feeling for the city has perforce become that of an insider-outsider: everything in London is familiar; yet everything in it seems to me as strange’. As Jerry White explains in his discussion of Absolute Beginners elsewhere on this site, it was among the black, rather than white, populations of London that MacInnes ‘staked his particular claim of belonging, of sympathetic identification, of personal politics’, with this being demonstrated by the fact that his two later London novels continue to reflect their author’s interest in black characters, culture and music. As White also qualifies, however, MacInnes was ‘never really able to become more than an outsider’ within the black community too. One thing the author and his black friends did share, however, was London and it is to this frustrating, beguiling location that City of Spades returns again at its close. For, in a final section entitled, ‘Johnny Fortune leaves his city’, that irrepressible character echoes the opening sentiments of the novel by reminding us: ‘This is my city, look at it now!’

Kate Houlden teaches English at Queen Mary, University of London. She works primarily on questions of gender and sexuality in postwar Caribbean Literature, although she also has an interest in postwar British literature and Australian fiction.

References

Colin MacInnes: City of Spades, 1957; Absolute Beginners, 1959; Mr. Love and Justice, 1960; England, Half-English, 1961

Colin MacInnes and Erwin Feiger: London: City of Any Dream, 1962

John Williams, ‘Book of a Lifetime: City of Spades, Colin MacInnes’, Independent 4th August 2006

Francis Wyndham, ‘Introduction’ in Visions of London, 1969

All rights to the text remain with the author.