Séamas Duffy

Fowlers End is a special kind of tundra that supports nothing gracious in the way of flora and fauna … in (its) soured, embittered, dyspeptic, ulcerated soil. Fowlers End is barren of everything but weeds.

– Gerald Kersh, Fowlers End

Fowlers End opens with the central character Dan Laverock, a young educated man from a comfortable middle class family who has failed miserably and painfully in business, taking a job as the manager of a dingy cinema in the bleak outer suburbs of north London in order to make ends meet. The period is never precisely stated, but it is obviously towards the end of the silent film era: Mussolini is in power, the depression is starting to bite, and as the agitation in Cyprus for enosis with the Greek mainland is at its height, this would tend to place the novel’s events as happening around 1931. As a place Fowlers End is almost a gazetteer of festering stink industries: a steel tube factory, a glass factory, ‘the grimmest, noisiest, and smokiest railway terminal in London dealing in scrap iron, coal and splintered timber’, and a spectacularly hideous chemical plant which produces sulphuric acid:

a Brobdinagian assembly of alchemical apparatus out of a pulp writer’s nightmare as it sprawls under a cloud of yellow … between great hills of green-black and grey-mauve slag

It is also a pretty rough neighbourhood with mass unemployment and widespread petty crime, a place where ‘thugs rest between felonies’ and Greek barbers cut up their faithless girlfriends in the bath. However, a series of unfortunate accidents in youth has left Laverock with the physiognomy of a gangster, and the proprietor of the Fowlers End Pantheon, Sam Yudenow, calculates that Laverock can survive where his previous managers have succumbed to the terror of local gangsters.

It is also a pretty rough neighbourhood with mass unemployment and widespread petty crime, a place where ‘thugs rest between felonies’ and Greek barbers cut up their faithless girlfriends in the bath. However, a series of unfortunate accidents in youth has left Laverock with the physiognomy of a gangster, and the proprietor of the Fowlers End Pantheon, Sam Yudenow, calculates that Laverock can survive where his previous managers have succumbed to the terror of local gangsters.

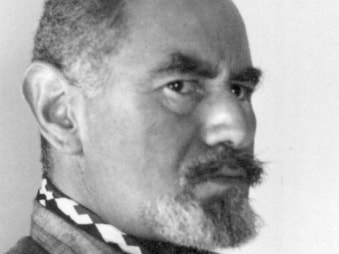

Gerald Kersh

Not many aspiring writers begin their publishing careers by having a debut novel withdrawn on the very day of publication due to threats of libel, and in even fewer cases, one might suppose, would the outraged litigants be members of their own immediate family: Gerald Kersh was not a man to do things the easy way. Subsequent bibliographic (and bibulous) misadventures saw him buried alive by the Luftwaffe, surviving intact but losing a valuable manuscript; then escaping with a small head gash and minor concussion when attacked outside a pub by a maniac with a hatchet and a knife, leaving a permanent scar on his left arm from the wound; there were also stories of an almost fatal altercation with a giant octopus off Barbados which may or may not have been invented to retain the interest of a female admirer – one feels Hemingway would have approved: indeed one of his works was described as ‘written … in pseudo-Hemingwayese’ (TLS, 09/09/60).

Much of Kersh’s fiction has the same picaresque quality as these episodes from real life, and in retrospect, the volume of his literary output seems phenomenal: there is scarcely a popular genre (crime novels, war stories, biography, science fiction, comedy, short stories, newspaper articles) in which he did not dabble or a form of media with which he did not experiment at one time or another (BBC Radio comedy, scripts and narration for the Army Film Unit). It is fair to say that not everything he touched turned to gold: his art suffered to some extent by having to work on occasion with journalistic speed against commercial deadlines; and various critics have castigated his unevenness, lack of literary graces, and occasional tendency – at the zenith of imaginative flight – to miss the point. However, it is for a handful of novels that he will remain most widely known, and upon which his reputation rests.

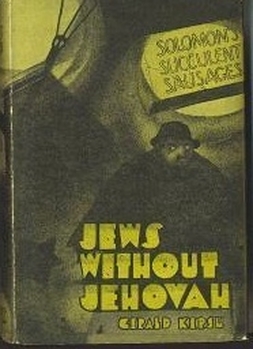

The first, ill-fated, novel was Jews Without Jehovah (published in 1934 when Kersh was 23) which drew on his upbringing in a middle class Jewish home in Teddington. The family circle was, by all accounts, full of the sort of eccentrics who were destined to re-appear later as characters in his literary fiction. Unfortunately for Kersh this first attempt sailed too close to autobiography for the comfort of some of his relatives – three uncles and a cousin – who took an intimate interest, recognised themselves instantly, and threatened to sue. As a result Jews Without Jehovah was withdrawn and, although the dispute was ultimately resolved in an amicable manner, the damage done to the book’s commercial prospects turned out to be irreversible, and very few copies survived (the number is believed to be about 50). Fortunately a number of review copies were sent to the Press prior to the novel’s publication, nevertheless those copies which remain available attract collectors’ price tags (this writer was quoted £600).

The first, ill-fated, novel was Jews Without Jehovah (published in 1934 when Kersh was 23) which drew on his upbringing in a middle class Jewish home in Teddington. The family circle was, by all accounts, full of the sort of eccentrics who were destined to re-appear later as characters in his literary fiction. Unfortunately for Kersh this first attempt sailed too close to autobiography for the comfort of some of his relatives – three uncles and a cousin – who took an intimate interest, recognised themselves instantly, and threatened to sue. As a result Jews Without Jehovah was withdrawn and, although the dispute was ultimately resolved in an amicable manner, the damage done to the book’s commercial prospects turned out to be irreversible, and very few copies survived (the number is believed to be about 50). Fortunately a number of review copies were sent to the Press prior to the novel’s publication, nevertheless those copies which remain available attract collectors’ price tags (this writer was quoted £600).

In order to gain some idea of the young Kersh’s early life and work, the conscientious researcher therefore needs to be content with a number of next best things: the 1934 Observer review of Jews Without Jehovah remains public domain, and brother Cyril’s attempt at working his remembrances of the Kersh family life into an art from survive in The Aggravations of Minnie Ashe – both texts are useful reference points. In the Observer review (10/06/34) of Jews Without Jehovah, the then Fiction Editor Gerald Gould unequivocally praised the book for its ‘raciness and reality … (and) … good, rich, salty, comedy-farce of the Ben Jonson type’. It also uncannily presages Kersh’s method to which he returned in Fowlers End some twenty odd books (and years) later:

He is concerned … not with the rich varieties of human nature, but, for the most part, with odious fools … (and) … their folly’s grossness! (An) account of greasy, greedy, cowardly humbugs tumbling from one disaster to another, and talking, talking, talking.

Cyril’s Kersh’s novel of a proud but poor Jewish family striving to get on in the suburbs throws welcome light on Gerald’s upbringing: the Kershes may have considered themselves to have been lower middle class, but even allowing for the fact that Cyril may have been better at literary camouflage than Gerald, if The Aggravations of Minnie Ashe is anything to go by, it was still pretty ugly, dirty and mean by modern standards.

Gould was not the only reviewer to see parallels between Kersh’s output and that of Jonson’s, and over the period of his literary career, Kersh seems to have been compared with an incredible variety of historical literary and artistic figures by successive reviewers, his work having been variously described as: ‘high spirited Gissing’, having the ‘idiosyncratic character-full monologue’ of Dickens, containing the realism of a Hogarth picture, the satire of a Swift, the classical learning of Robert Graves (carried very lightly, it was pointed out), as well as the Jonsonian comic invention first identified by Gould. Kersh aficionados will argue which is his best novel – Night And The City achieved, and has recently re-attained, cult status and The Implacable Hunter must certainly rank very highly – but Fowlers End contains Dickensian, Hogarthian, Swiftian, Gravesian and Jonsonian elements in abundance and is, for this writer, his finest work.

Fowlers End

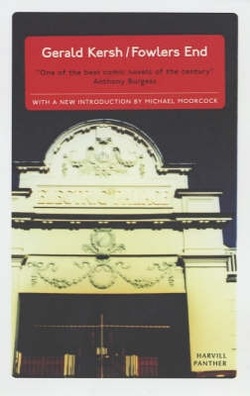

Much of the story in Fowlers End revolves around Laverock’s determination to escape from Yudenow’s shabby show business empire, having experienced a ‘speedy shift from fascination to revulsion’ when his employer’s true character is revealed through business dealings of questionable ethics. In Jonsonian fashion, the novel’s plot tends to be subjugated to character and dialogue; themes of fraud and ethical ambiguity predominate and, although there is a superabundance of incident, one could comfortably summarise the main story line of the 300 page novel in well under a hundred words (and indeed someone does, on the back cover of the Harvill Press edition).

The principal libris personae are Laverock, Yudenow, Baldwin (the indispensible Cinema factotum), Godbolt (Yudenow’s business rival, a born again fundamentalist, and anti-semite), June Whistler (Laverock’s sometime girlfriend), and the Greek brother and sister, Costas and Kyra, who run Yudenow’s grim catering subsidiary from, and make bombs in, a Dantean hellhole described by Laverock as ‘Landru’s kitchen’ (Henri Désiré Landru was a Parisian serial killer who was convicted on 11 counts of murder in November 1921. He was reputed to have disposed of his victims by burning them in his kitchen stove). Amongst the minor characters are Laverock’s Wodehousean old school friend Cruikback (who claims descent from King Richard III), Laylock the Chemist (permanently dressed in black and always conveying the impression of having just buried someone in the cellar), and Gutter the comedic ventriloquial Pork Butcher.

The novel is told in the first person of Dan Laverock, whose boss the cynical, shifty, grasping Sam Yudenow, the showbiz impresario is, according to Anthony Burgess (Yorkshire Post, 29/06/61), ‘as superb a creation (almost) as Falstaff’ – Burgess considered Fowlers End ‘to be one of the best comic novels of the century’. Sam’s entry onto the Fowlers End stage is unforgettable:

talking between hastily swallowed mouthfuls of himself … he threw back his head and sniffed; became mauve in the face, gagged, choked; blew into a big silk handkerchief … sighing with relief. He showed me the contents of the handkerchief, which might have been his brains.

It also doesn’t get any cleaner: Kersh in fact worked as a cinema manager at one stage of his career, and would have known that the silent films were invariably supplemented by musicians. In fact at that period the single most common employment for musicians was in accompanying silent movies: sometime a small orchestra in the evenings for the really posh ones (which the Pantheon isn’t), and perhaps a pianist for the matinees, but there was also a fair sprinkling of standard variety acts. At one point Laverock peruses, with a combination of dismay and horrible fascination, the list of ‘Live Bookings’ for the next three days:

‘Johnny Mayflower – Trick Skater; Johnny Lambsbreath – the Man Who Made the Prince of Wales Laugh; Eena – Oriental Contortionist; Hanky and Panky – Eccentric Dancers; The Tramp Juggler; Gritto – The Man Who Eats Bricks.’

His keen eye for detail delightfully recreates the bathos, the faded glamour and downright squalor of the dying days of this branch of variety in much the same way that Patrick Hamilton in Twopence Coloured elegises the transience of fleapit provincial theatre:

Live variety and silent films were in the dump. The ones I pitied most were the old music hall stars who had been idols in their day … who had rushed from music hall to theatre and from theatre to music hall without wiping off their makeup, putting on five or six acts a night. They (had once) earned up to a hundred pounds a week … and always in their minds was the memory of what they had suffered before … ‘Luck’ got them out of the gutter. But when times changed it was terrible to see the empty despair of entertainers whom everybody had known compelled to repeat their names two or three times … to a new generation of agents and managers. (T)he old comedians … raised nothing but derisive laughs in Fowlers End in my time … you hear the howl and see the bared teeth and the curled lip; and you perceive the cruelty that is fundamental to most (comedy).’

Kersh has an even keener ear for the timbre of the cockney voice (‘as sharp as scissors’ – VS Naipaul), and the word play is at times of almost Joycean proportions. In Sam Yudenow’s mouth the cockney dialect dances to the basso continuo of Hebrew and the wild rhythms of Yiddish (itself a language so onomatopoeic that one feels there is scarcely an adjective that needs translation). With his homespun aphorisms deployed in a style as eclectic as it is amusing, Yudenow delivers a constant flow of pun (conscious and unconscious), perverted cliché and alliteration, liberally sprinkled with the juxtaposition of medial consonants, reversed dipthongs, and an assortment of latter day malapropisms and common or garden howlers.

“How do you like the name Pantheon? I made it up.”

“Greek?” I suggested.

“It’s Gveek for cinema … ya need an edyacation in show biz.”

Sam Yudenow seems to be something of a hybrid between Solly Schwartz from Kersh’s earlier novel The Thousand Deaths of Mr Small and the character of Uncle Mendel (‘the business genius’!) from brother Cyril’s The Aggravations of Minnie Ashe, whereas Baldwin (the drudge who becomes Laverock’s soulmate) seems to have sprung straight from Kersh’s imagination.

And while Yudenow is a grasping capitalist speculator, Baldwin is a working class autodidact, whose doctrinaire, and eternally inconsistent, Marxism causes him to detest the lumpen proletariat (“the stinking rabble”) almost as much as the aristocracy and the grand bourgeoisie (“Down with the King, down with the Queen, up with the Bolsheviks”). In contrast to Yudenow’s high flown bombast, Baldwin’s dialect is to Laverock’s ears ‘the lowest-down kind of Cockney I ever heard in my life – snorts, grunts, labials, glottal stops, rhyming slang and all … he juggled his dipthongs, mewed his vowels, swallowed his consonants, used prepositions to end sentences’. He is the possessor of a compendium of phonetic effects, rhetorical devices, and linguistic idiosyncrasies which ‘play pocket billiards with subject, predicate and object’.

But, as Laverock begins to grasp only slowly at first, Baldwin understands language only too well, and over bottle of Bass in ‘The Load Of Mischief’, the Stygian local hostelry that manages to be as cold as the grave and oppressively stuffy and clammy at the same time, a host of literary reputations queue up to be slaughtered – outrageously but hilariously – by Baldwin’s critical sword. English authors are dealt with first, Dickens being singled out as the principal ringleader (“phony to the backbone. Never saw one … [a villainous character] … except with a Police inspector at both elbows), then G.K. Chesterton (“as bad as Dickens, if not worse”), followed by Shakespeare (“ ’e done ‘is best within ‘is limitations”), before Baldwin reaches across to the Continent to excoriate Zola (“got it all out of the newspapers”) and for good measure Tolstoy (“a crackpot”): one has an impression of the authorial voice intruding here.

Laverock is iniquitously ugly but he nevertheless appears to attract (or at least engage the sympathy of) women of all types; he meets June Whistler, an eccentric but essentially harmless civil servant (‘her expression was intended to be haughty, aloof, disinterested, blasé – the femme fatale but it didn’t quite come off’). Due to a misunderstanding she perceives him to be a desperate crook and here Kersh turns a brilliant pastiche of the well brought up middle class naïf intrigued by the glamour of gangland lowlife and enchanted by its villains. After a weekend spent in June’s boudoir, Laverock returns a few days later to be causally informed by her that she is ‘five days pregnant’ and already has a name for the child.

Laverock also has a surrogate fling with Kyra from the kitchen (‘[eyebrows] … like a kitten’s tail’ … ‘a beautiful girl in a duck legged Cypriot way – heavy lidded, heavy haired’) who entraps him into political intrigue in an entertaining parody of the plot of Conrad’s ‘The Secret Agent’. With propitious timing, Laverock meets an old school friend, Cruikback, who persuades him to invest in a land purchase scheme – land which Cruikback knows that Sam Yudenow needs in order to expand his business empire. Laverock then sells the land to Yudenow at enormous profit which makes him enough money to set him free of Fowlers End for good. The novel ends with Laverock and his friend Baldwin steaming away to South America on a freighter.

The book has a number of sub plots: the cinema’s female pianist is an alcoholic who can only be kept sober with constant resort to subterfuge; Laverock has to survive relentless harassment from local small time gangsters (‘raiding parties [of] indescribably repulsive … young bloods … out for mayhem’); and then there is Godbolt, the miser, ‘a hideously ugly little man, cold and viscous … (who) lived on stale bread, margarine and tea’. Godbolt was once a righteous proselyte of the chiliastic Nakedborn sect:

one of the infatuated devotees of a demented tinker who not only preached the Second Coming, but more than hinted that he was it … (and who) … married the entire choir before running off to America.

Godbolt wages a holy war against the heathen Yudenow (‘a micrographer in contractual small print and … master in conveyancing’), who has tricked him into leasing the Nakedborn’s now disused church for conversion to a ‘Super Cinema’.

So, Mr Godbolt went to see his solicitor in Edmonton and they went over the lease clause by clause … while the Said Sam Yudenow had agreed not to conduct a Clay-Pipe Burning Factory, a Brothel, a Tannery, a Soap-Boiling Factory, a Public Slaughter-House, or a Glue-Boiling Factory on the Said Premises – and much Fowlers End would have cared if he had conducted the whole lot (together) – there was nothing in the lease about … places of public entertainment.

Kersh’s instinct, as in many of his other novels, naturally gravitates towards the lower end of the social scale. But despite the gallows humour, the ironic humanism, and what one Michael Moorcock called his ‘drinker’s acceptance of human failings’, Kersh shows no authorial interest in poverty or in class conflict for its own sake: he would never be mistaken for an angry young man. His stance is not only too detached, but he is also far too interested in character and motivation to engage in harangue. And whilst he has been described elsewhere as a ‘moral rhetorician … a latter-day Bunyan in our Uncelestial City’ (Night and the City) and ‘extravagantly brutal’ (Prelude To A Certain Midnight), Fowlers End is one of that rare and delightful species in the Kersh canon – a comic dystopia; a ‘perpetual twilight’ peopled by minor grotesques.

Credit – Geograph website and Danny Robinson

Credit – Graham Johnson’s website

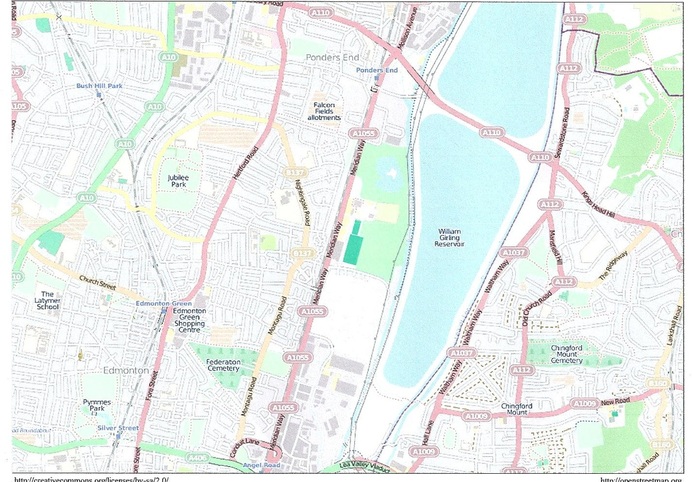

Perhaps as a result of the furore surrounding the publication of Jews Without Jehovah, Fowlers End bears a stern introductory warning on the frontispiece that the people and places in the novel are wholly fictitious. Kersh, however, seems anything but coy about the location of Fowlers End and anyone who seeks this mythical otherwhere,this anti-Jerusalem, is provided with the clearest and fullest directions:

ahead up Camden High Street towards … Holloway, where the jail is; and past the allurements of this enclosed space, through the perpetual twilight of Seven Sisters Road which takes you to Tottenham. Go north to Edmonton and Ponders End … farther yet bearing north-east (to) Fowlers Folly … only a mile farther on … is Fowlers End.

Here the city gives up.

This is it.

Actually, this isn’t ‘it’ because, of course, a mile north east of Ponders End High Street places the location of the novel somewhere in middle of the northern basin of King George’s reservoir. Unless one assumes that Kersh intended Fowlers End to be some submerged dystopia after the fashion of a drowned Atlantis, there is some working out to do. Fortunately the novel is laced with plenty of geographical hints and, with a little imaginative research, one can work out that Fowlers End is actually, like Lowry’s industrial landscapes, a composite picture – part real, part imaginary; and the townscape which Kersh paints here is composed of disparate parts of Ponders End and Lower Edmonton with exaggerated, but not wholly fictitious, scenes of the stink industries of the lower Lea Valley added to the canvas to provide colour.

In Kersh’s day, this part of the lower Lea Valley did have a pipe works, as well as a munitions depot, in Ponders End, and there was a shunting yard of old engines and wagons at Angel Road, Edmonton, not to mention factories producing white lead, tubes, light bulbs, jute, linoleum as well as the inevitable gasworks. And although the Lea marshes figure in the background – ‘it doesn’t have to (rain) … because more water comes out of the ground than goes into it’ and the fictional, but much posher, town of Ullage (‘three miles from the Hertfordshire border’ and probably based on Waltham Cross or just possibly Cheshunt) seems to derive from the word play on ullage = seepage, leakage – neither the river Lea nor the Lee navigation, nor the many watercourses which drain the area are directly mentioned in the book.

And this is strange, because the River Lea is perhaps second only to the Thames as a river that has had both an effect on the consciousness and affections, not to mention the recreational life, of Londoners, and in the breadth of its literary references. One can for example think of Izaak Walton’s instructive and serendipitous wanderings there in the company of ‘Venator’ and ‘Auceps’ and indeed one of the oldest literary landmarks in the area is Bleak Hall, the watering place of Walton’s ‘Piscator’ at Cook’s Ferry (close to what is now known as Pickett’s Lock); although there is some dispute over the exact location and whilst the literary-historical evidence may seem weak, local anecdotal tradition remains strongly in its favour. There is Arthur Morrison’s evocative depiction of the bleak limey lower Lea banks by Abbey Marsh in The Hole In The Wall, the riparian equivalent of Conan Doyle’s Victorian gaslit, foggy London streets, and a succession of books by Jim Lewis on the historical development of the river and its environs; even Iain Sinclair provides an almost wistful description of the ‘heartbreaking sunrises’, ‘epic skies’ and ‘picnics in the chill autumnal mists among the sunflowers’ and ‘effluent-fed weeds’ of the Lea (in Lights Out For The Territory, and London Orbital).

He also believes (‘White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings’) that ‘Southwark (with) the City, Whitechapel, and Clerkenwell … holds its time’; the Lea, it might be argued, with the largest incinerator in Britain and a square mile of sewage works, holds its smell. It also holds an official, as well as secret, and bizarre history: famous for its industrial heritage, where the light bulb, the computer and the toilet roll were invented; infamous for being the home of the Witch of Edmonton (burnt at the stake in 1620), and a stronghold of non-conformism (‘the head of the serpent’ according to an Anglican bishop in the tumultuous year of 1666); historical accounts also mention the ancient fair of Edmonton ‘with all its mirth and drollery, its swings and roundabouts, its spiced gingerbread, and wild-beast shows’ and where in 1820 a lion tamer was eaten by one of his charges ‘a magnificent Barbary lion.’

According to Kersh, ‘… at the High Street … where the tram line ends (is) where Fowlers End begins’. The café at this tram terminus is run by ‘a bald old lady (who dispensed) tea ‘notorious for its potency and … mysterious pies’. In fact, there was originally a Tramcar Café (later the Trolley Bus Café), in Tramway Avenue almost exactly half way between the Lower Edmonton and Ponders End railway stations, although the building which housed the café is now demolished, the vacant ground being until recently the makeshift forecourt of the North London Motor Company. In the era in which Fowlers End was set, there was still a gap between Tramway Avenue and Ponders End High Street, which disappeared as residential and other developments expanded took place in the late 1930s – when the real life Sam Yudenows took hold. Interestingly there was also a non-conformist church (now the Tramway Christian Fellowship) right beside the original tram terminus and it is tempting to identify this as the tabernacle of Kersh’s fictional Nakedborns.

Not that the idea of converting churches for public entertainment, nor the existence of messianic and millenarian sects as preposterous as the Nakedborns were entirely imaginary: perhaps Sam Yudenow’s Pantheon is, like the rest of Fowlers End, a composite – for a number of cinemas and theatres in the area had been converted (Godbolt would no doubt have said ‘desecrated’) from ecclesiastical usage; and the Nakedborns were probably based on the Agapemonite sect (Greek: Agapemone = abode of love), whose views on ‘the true station of womankind’ were certainly unconventional, and whose one time leader John Smyth-Pigott proclaimed himself to be the Messiah – whilst not exactly marrying the entire choir, he was nevertheless alleged to be going through ‘a demanding succession of “spiritual” brides, reputedly 7 a week’ (see the Clapton Website at: http://www.clapton.freeservers.com/photo3.html.)

Interestingly the Agapemonite sect was large enough, and affluent enough, in the late Victorian period to finance the building of one of the most magnificent churches in the area before its demise in the wake of the Smyth-Pigott scandal. It was then taken over by a neo-Jansenist sect known as the Ancient Catholic Church which was neither especially ancient (being post-reformation) nor particularly Catholic (‘clairvoyance medium’ on Thursday nights), and is presently used by a Georgian Orthodox congregation. The church has some quite outstanding, and ecclesiastically untypical, stained glass windows and the exterior is still adorned with apocalyptic architectural symbology of Lion, Man, Ox and Eagle; it also retains classic Blakean adornments of a spear, a chariot of fire, and a sheaf of arrows (of desire, no doubt!).

Taking all of Kersh’s historiographical allusions into account, one feels this must be the place he had in mind. One can agree with Gerald Gould that ‘if the account (of Fowlers End) were presented as a study of a race, it would be grotesquely untrue; as a comic picture of a few persons, it is grand’. A dystopia of gas works, greeny mauve slag heaps, jail bait and knife gangs: as Sam Yudenow says “The Pantheon don’t cater for Royalty … and Fowlers End ain’t Park Lane”.

Novels by Gerald Kersh

First UK edition:

· Jews Without Jehovah, 1934

· Men Are So Ardent,1936

· Night And The City, 1938

· They Die With Their Boots Clean, 1941

· The Nine Lives Of Bill Nelson, 1942

· The Dead Look On, 1943

· A Brain And Ten Fingers, 1943

· Faces In A Dusty Picture, 1944

· An Ape, A Dog And A Serpent, 1945

· The Weak And The Strong,1945

· Prelude To A Certain Midnight,1947

· The Song Of The Flea, 1948

· The Thousand Deaths Of Mr Small, 1950

· The Great Wash, 1952

· Fowlers End, 1958

(published in the US in 1957)

· The Weak And The Strong, 1959

· The Implacable Hunter, 1961

· A Long Cool Day In Hell, 1965

· The Angel And The Cuckoo,1967

· Brock, 1969

Bibliography

BLAKE, William: Jerusalem (from ‘Milton’), 1804

KERSH, Gerald: Jews Without Jehovah, 1934

KERSH, Cyril: The Aggravations of Minnie Ashe, 1970

LEWIS: Jim: London’s Lea Valley, 1999

MORRISON, Arthur: The Hole in the Wall, 1902

SINCLAIR, Iain: Lights Out For The Territory, 1997

SINCLAIR, Iain: London Orbital, 2002

SINCLAIR, Iain: White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings, 1987

WALTON, Izaak: The Compleat Angler, 1653

Further Reading

Harlan Ellison’s Gerald Kersh website: http://harlanellison.com/kersh/

Pat Cryer’s Social History of Edmonton Website: http://www.1900s.org.uk/index.htm

British History Online: Protestant Non-Conformity in Lower Edmonton:

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=26943

All rights to the text remain with the author.