Suneel Mehmi

London is a centre and a focus for queer life and culture. The three overlapping stories in London Triptych explore the queer subculture of London and its other world that is differentiated from the everyday experiences of straight Londoners. Indeed, speaking to a journalist shortly after the publication of London Triptych, the author said: ‘I wanted to capture a hidden London, a secret and very sexual cartography of the city that is often occluded, marginalised, and ignored. It was very important to me that the nocturnal and erotic aspects of the city were delineated and represented.’ The book is about three different Londons and three different histories of London, all told through the perspective of gay men, hence the title which refers to the form of painting which is composed of three different sections. It is a novel about three differing historical experiences of the city – about freedom, love and loss – about the nature of desire and its contexts.

It begins in 1954 with an observation by an unnamed painter, a man concerned with his age and who has found new inspiration for his art, about a newspaper report of an arrest of ‘some poor sod caught in a public toilet’. It then moves swiftly to 1998, to another unnamed man, a gay prostitute, being released from prison and recounting his personal history. Then we are transported to 1894, to a man named Jack Rose, another gay prostitute.

The novel continues this sequence of shifting dates and experiences of queer life in London. The narratives of the three men are related to each other in a number of ways but the major similarities are that they are all narratives of discovering freedom, love and heartbreak, the pleasure and the danger in freedom and love. The narrators all learn, in their own different ways, the knowledge of what it means to be free, what love and its pain mean and they all become wiser.

The theme of representing the city is central to the book. There is the representation of three different historic Londons: Victorian London, the post-war London of the 1950s and the London of at the close of the twentieth century. In his afterword, the author writes that he uses the city almost as ‘a fourth character’. Jack Rose’s London is the London of the poor. Victorian Bethnal Green, the scene of his childhood, is described as a ‘stinkin’ hole’ and his London is ‘this bloody shithole city’. Indeed, his East End stinks of faeces the whole time and there is no running water. There is a vivid sense of the fate of the poverty-stricken Londoner given in his account of the beginnings of his life, which involves an abuse-filled childhood and then in his subsequent encounter with need after the famous trial. Jack Rose’s freedom in this London is ‘a way of life that would show (him) things beyond that narrow horizon of poverty and survival’. Whoring, with its golden chains and its golden cage, takes him from Bethnal Green to Fitzroy Street in Bloomsbury and then to Westminster, behind the Houses of Parliament. It also changes his experience of the city. He is taken for rides in Hyde Park, for tea at the Ritz or champagne at the Café Royal. He is even taken to stay at the Savoy.

The painter’s London is set in the aftermath of war and deals with a London that hates the gay man; the city of a repressed homosexual who doesn’t dare to put himself outside the law to achieve his desires, but sublimates them through the act of painting and moves in an artistic circle full of others doing the same. He lives in Barnes and is part of a life drawing class in Mortlake, which stands defiantly as a bastion of culture in the rubble of bombed houses. His experience of London, along with that of other survivors of the wartime bombing raids, is of the danger of being in the city; he has himself been widowed by the war. The dangers that most threaten him, however, are not of war but of hatred and intolerance and the constant fear which can colour a whole life and experience.

The unnamed narrator of 1998 comes to London to escape the narrow confines of the work-a-day middle class life, to‘find another world’ or to ‘formulate a way of life radically at odds with what was expected of (him)’, to become somebody else. He wants to lose himself in the city, to disappear, but also to become ‘stronger, more wicked, and more profound’. He represents the gay man that is irresistibly drawn to the capital, for whom the city confers identity, for in an interview in Polari magazine, shortly after the publication of the novel, Kemp asked ‘How many of us have moved to the city and reinvented ourselves according to how we would like to be?’ His first experience of the city is terror, the unutterable terror of anonymity and having no place (literally no place to stay). His London is the party capital, the London club scene, the haunts of the whore, and through the oldest profession he wraps himself ‘inside the moods and colours of this city’.

The city fulfils this gay man’s hedonistic urges, since ‘London meant having everything’, but the life he leads keeps ‘intimacy at bay’ and he has to learn how to love in the city, how to rise about the anonymity and security it gives him in imposture, lies and whoring. In a significant passage he talks about how the city may itself interfere with the true recognition of the self, how it may swallow a person entire: ‘London made me, but it made me invisibly, like a roll of film that once developed reveals nothing more than an identical series of blanked or blurred over-exposures.’ For this gay man, paradoxically, London both allows the development of self, but also threatens to consume the self. He has to negotiate his way between the enabling and the constraining aspects of the capital.

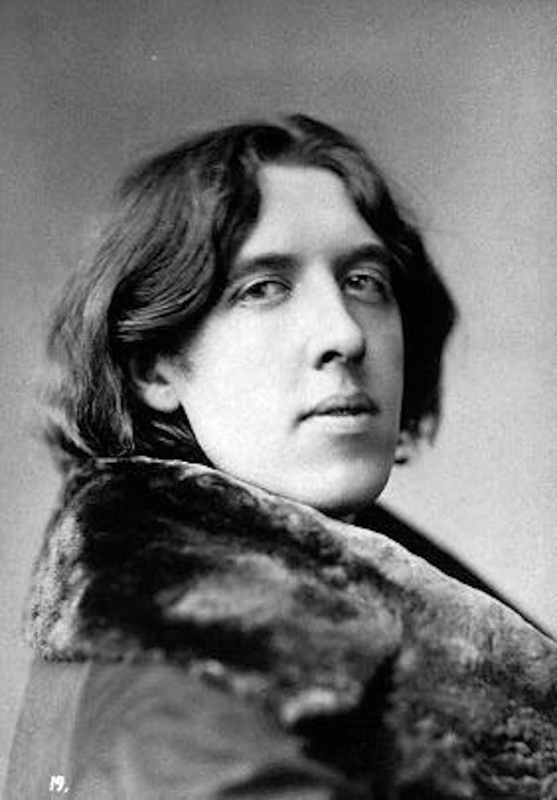

All these Londons are connected. Oscar Wilde, a character reimagined in the novel, says, for example that ‘London is like a drying pool of vomit at which pigeons are mindlessly pecking with no hope of nourishment’. His idea of London is not only resonant with the poor man, Jack Rose’s description of it in terms of a toilet, that which deals with what is unwanted, emitted from the body, but also with the gay man’s idea of it in the 1990s who finds that the hedonistic lifestyle it can offer is not enough for the body and the self, that it is a distraction and an unwise choice of youth. Wilde also says of the capital that it is ‘this cold blue city, where danger is so near to pleasure’. All the gay men experience this tension between danger and pleasure: one is violently attacked in a public toilet, a haunt of the gay man, and fears imprisonment if he expresses his sexuality; another is constantly aware of the threat to life that his lifestyle in the city involves, in terms of human killers and killer diseases like AIDS. The author himself writes that the Londons are all connected in a fundamental way and tied to the central theme of freedom in the work because ‘(f)or all three men, their experience of London is, essentially, one of liberation.’

Besides investigating the queer histories of the city over time, the book investigates other deep themes around the idea of freedom. The conception of the novel seems to have been inspired by a reading of Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality. Foucault’s interest in that work was in how the subject is created and how the individual is constituted. He argued that in the western world during the 18th and 19th centuries, people’s identities were increasingly conceived of in terms of their sexuality. London Triptych also explores how modern identity and sexuality interact in different historical periods, when society-wide conceptions of homosexuality and the homosexual were transformed. It is also a history of sexuality and of the constitution of the individual in social and political space with particular emphasis on the idea of freedom: what it means to be free, how to find freedom.

Each narrator in the novel is differently placed in time, and there are differences and similarities which we are invited to find for ourselves, since the structure is in the form of the triptych which invites comparison and contrast. The repression of the painter in the post-war period which legislated against homosexuality is contrasted with the freedom of the Victorian male whore before the landmark Oscar Wilde trial changed ideas about and attitudes to homosexuality; and then there’s the freedom of the gay man in the closing decade of the twentieth century, a freedom which has to negotiate the effects of capitalism and the pressures of urban life in which the self may lose itself.

The personalities of the three voices in the novel are very different. Jack Rose is a very passive character who is controlled by circumstance and by others, first the pimp that introduces him to the life of whoring, then by the enemies of Oscar Wilde. The painter is a man who has been afraid to live his life and enact his desires and has almost let life slip him by. His fear of the law and of the exposureof his sexuality has coloured his experience to such an extent that he has been unable to find out who he is. He lives in a prison of his own making. In stark contrast, the male prostitute of the 1990s is hedonistic and decadent, unashamed of his sexuality and lives a life led by his desires.There are also similarities between the three voices. Each has a difficult relationship with his father. Each is threatened by the law and prison, symbolically and literally. There is some overlap between the history of the characters too, as the immediate experience recounted in the novel is represented again as the memory of the old as the different narrators interact with each other and with other characters related to them.

The novel ends on a positive note, with Jack Rose leaving London for a new beginning, the release of the second narrator in the series from prison and the painter finding new energy for his art, despite or because of his heart break. Each of the gay men is liberated from the prisons, symbolic and literal, that have constrained their lives.

Beyond its status as a research-driven meditation on the history of gay sexuality and the interaction of the personal with the political, how the politics of sexuality affects our outlook on life and our freedoms, the writing of the novel is fluent and engaging. The characters are compelling and we see each of them develop. Kemp does what he intends to do, ‘giving the voiceless a voice’, as he terms it in his afterword. The result isan ambitious work which has substance and which reinvents history and reinvents London, outlining its possibilities for personal growth and the potential pitfalls for the unwary.

Suneel Mehmi is a PhD researcher at the University of Westminster. He lives in East London and his research focuses on the intersection between law, literature and the cultural unconscious. He has written various book reviews on the topic of London in fiction for the Literary London Journal.

All rights to the text remain with the author.