Andy Wimbush

I’m afraid I’ve told you a fib. I’ve led you here with the understanding that you’re going to read all about how B.S. Johnson’s Albert Angelo is a London fiction. As it turns out, that’s not really the case. You’ve been had. The truth is, Albert Angelo isn’t really a London fiction at all.

Perhaps you’d like to turn on your heels now, and leave, disgusted and betrayed. But before you go, I should perhaps say that I wasn’t fibbing about the London part.

Perhaps you’d like to turn on your heels now, and leave, disgusted and betrayed. But before you go, I should perhaps say that I wasn’t fibbing about the London part.

Albert Angelo really is a book about this city and not any of the other ones. It even mentions the A to Z. Twice! How many novels can you say that about?

No, the fib was, appropriately enough, in the fiction part. This is because although Albert Angelo is a novel, it’s more than a little uneasy about being one. It certainly doesn’t want to be a mere story, at least in the usual sense of that word. It wants to be truth. We know this because after 163 pages of what seems like a novel, albeit a rather unconventional one, the narrator breaks down mid-sentence and cries ‘oh, fuck all this LYING!’.

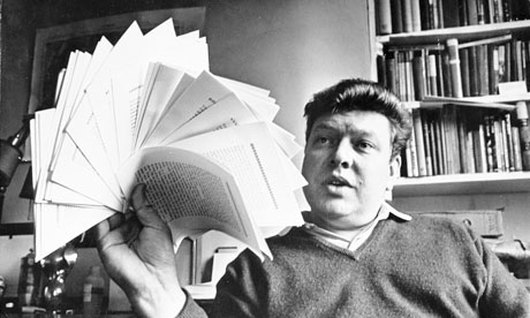

The book doesn’t end there, of course. It enters a section called ‘Disintegration’ in which someone who sounds a lot like B.S. Johnson emerges from behind the curtain of fiction to tell us what he was trying to do. Johnson, who published seven novels between 1963 and 1973 and then killed himself at the age of forty, was a disciple of novelists who had pushed their medium to its very limit: writers like James Joyce, Laurence Sterne and Samuel Beckett. Johnson felt that most novelists of his generation hadn’t really come to terms with the discoveries that these writers had made, and continued to spin stories as if Ulysses or The Unnamable had never been written. Johnson wanted to do something different: ‘telling stories is telling lies’ opines the Johnson-like persona in the penultimate chapter of Albert Angelo. ‘Im [sic] trying to say something not tell a story’.

The trouble was that Johnson was actually very good at telling stories, even if (or perhaps especially if) those stories were barely veiled accounts of his own life experiences. Before Albert Angelo starts to unravel, it is a marvellously readable yarn about a man in the early 1960s who aspires to be an architect, but through lack of work must settle for making a living as a substitute teacher in a string of struggling inner city London schools. ‘It’s a tough area, mate,’ says his father as he learns about Albert’s latest assignment, ‘I shouldn’t think they get many teachers to stay’.

Although Albert says he feels ‘fairly confident’, Johnson shifts the burden of that confidence onto YOU, dear reader, by switching from the third person narration at the start of the novel to a rather discomforting second person narration as Albert arrives at the school:

The Headmaster is formal, apart, preoccupied. […] As he takes you along square stonefloored tunnels to your classroom he expresses his dislike, oh so politely, by finding out why you are not in a permanent teaching post when he hears you are trained and qualified.

Albert reels off jokes he has told many times before, in an attempt to win each class over and keep them quiet. He struggles to communicate with pupils who speak languages other than his own. He can’t quite keep his lessons on geology from straying into to architecture. He sometimes loses his rag and hits a child. And all of his failings are related accusingly at you.

Johnson switches grammatical persons again later on, opting for the chummy unity of the first person plural to narrate Albert’s trip down the pub with his old friend and fellow ‘London kid’ Terry: ‘we stop there at Aldgate for cockles or prawns at Tubby Isaacs’, but more often we will go straight on down to Cable street’. Albert’s memory of a dismal camping trip to Ireland with his ex-girlfriend Jenny is told through a distancing ‘they’. But Johnson’s best innovation comes in a transcript of one of Albert’s doomed geology lessons. On the left hand side of the page is the dialogue between Albert and his inattentive students, while on the right hand side we get Albert’s thoughts: his snap judgments and self-critical commentary, his sarcastic asides and his lengthy daydreams. ‘Ooh,’ says a pupil, after Albert gets angry with them, ‘and he’s supposed to be a teacher too.’ In the opposite column is Albert’s reflection: ‘Not supposed to be human if you’re a teacher’. The chapter makes you realise just how rarely fiction has granted an internal world to teachers, and how often – think Nicholas Nickleby, Molesworth, Mathilda, Harry Potter – the pupil’s perspective alone is presented to the reader. Johnson, like Evelyn Waugh and Charlotte Brontë before him, describes a teacher in all his all-too-human glory.

Of course, Albert wants to be doing something other than teaching, and retreats to the staff room to sketch the skyline during his lunch break. As he criss-crosses London from home to school and school to pub and back again, Albert sees the city with an architect’s eye. He admires the ‘great squat stock-brick arches’ of Kings Cross station, the ‘miraculous’ proportions of St. Paul’s Hammersmith, the ‘graceful’ curves of the Hammersmith flyover and the ‘beautifully-kept’ Georgian houses on Cable Street. He’s less convinced by the ‘cantilevered shell’ of Stamford Bridge, and some ‘uncomely flats’ in Myddleton Square, but, like most of his contemporaries, reserves his deepest scorn for the ‘pseudo-Gothic excresences of Scott’s St Pancras’. In 1969, just five years after Albert Angelo was published, the building was very nearly torn down, such was the public loathing for Victoriana. Euston’s Victorian Doric columns had already met the wrecking ball in 1962. Albert wonders whether ‘it is fatal to live so near to St. Pancras for an architect’. ‘Certainly,’ he concludes, ‘it would be to bring up children here: their aesthetic would be blighted.’

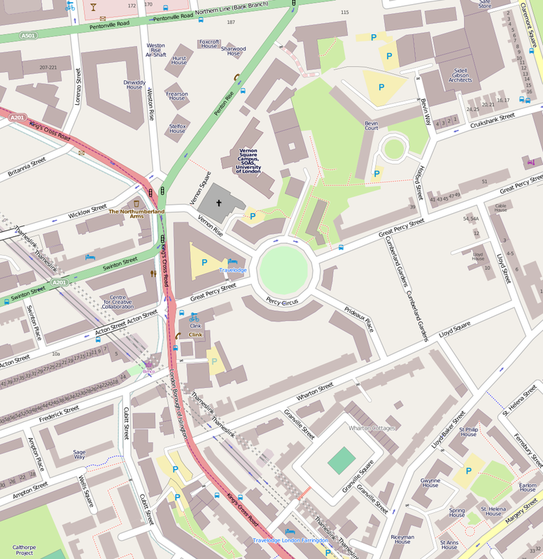

Even if today’s Londoners have rehabilitated some of the buildings that Albert scorns, his irritation with ‘non-Londoners’ on the tube is still keenly felt: ‘foreigners, who do not know their ways,’ and ‘upfortheweekenders who stand on both sides of the escalator’. It’s mundane flotsam like this, as well as the nod to the A to Z and to numbered bus routes that make this a Londoner’s novel. Albert is even named after his place in the city: ‘Angelo’ becomes his nickname after some of his unruly pupils find out that he lives in Percy Circus, in Islington, an address that, needless to say, was far less desirable in 1964 than 2013. Johnson’s slavish attention to London’s geography is yet another reason why the label of ‘fiction’ fails us. When the curtain falls in the penultimate chapter and Johnson starts to reveal the inner workings of his novel to the reader, he explains that he had so misremembered the real holiday behind Jenny and Albert’s ill-fated camping trip that he had to ‘pinch the scenery’ from North Wales. No pinching is necessary when it comes to London: the capital is there, in stucco, stone and concrete, still recognisable fifty years later.

For all its architectural marvels, however, London is still a place of yawning gulfs between rich and poor, and of political strife. Albert dubs Cable Street the ‘Cablestrasse’, no doubt alluding to the ‘Battle’ of 1936 which saw trade unionists, anarchists, and Jewish and Irish groups face down Oswald Mosley and his army of black shirted fascists as they marched through the ethnically diverse East End. In another of Johnson’s novels, the protagonist lists ‘Socialism not being given a chance’ as his main grievance against life, and Johnson felt himself ‘enlisted’ to the proletariat side of the class war. Politics seeps into Albert Angelo too: the Disintegration chapter describes Johnson’s intention to provide ‘social comment on teaching, to draw attention, too, to improve’.

But for all these ambitions Albert can still seem a bit of a snobbish twit at times. Non-white and immigrant Londoners are never main characters in the narrative, and the language used to describe them often makes for uncomfortable reading. Albert’s taste for Georgian buildings in an age of concrete Brutalism betrays his bourgeois aspirations, and at times he seems only dimly aware of the gap between his own status as an upwardly mobile educated man of working class background and the deprivation of those he is paid to teach. This is most obvious when he makes the terrible mistake of calling his pupils ‘peasants’ in a moment of extreme frustration. Later on, he naïvely wonders whether it was the ‘country bumpkin associations’ of the word that so upset them. Johnson is, of course, indicting himself in all this: mining his own prejudices and failings, and turning that into a political act. In the end, Albert stands up for his class, defending the schoolchildren against another teacher who wants to reform their ‘bad and slovenly’ speech. Albert replies that such words cannot ‘be meaningfully used about speech’ and that ‘speech conventions’ are changeable. Working class children, he adds, are often at the frontline of such linguistic innovation, while the upper classes, and especially the Queen, lag behind.

Literary experimentation and political didacticism might make for a turgid read in the hands of anyone less gifted than B.S. Johnson, who was also a master humorist. Like his masters, Joyce and Beckett, Johnson blended bleakness with comedy in almost all his work. While the biggest laughs are to be had elsewhere, notably in Johnson’s very funny Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry, Albert Angelo has some priceless moments. Much of the best comes in the dual-column geology lesson, particularly when Albert has to stifle his own guffaws when the kids says something funny: ‘—Albert’s got new suedes on. — Cor! dig them broffel-creepers!’ And when Johnson does eventually channel Nigel Molesworth in a section consisting of the pupils’ poorly spelt verdicts on ‘flabby Chops Albert’, there are some inspired insults to be had: ‘ON THE WHOLE YOUR STUPID AND YOU ARE A FAT FOMF OXEN NIT LOLOP RABBI FART-FACE’ or ‘Evry time he gets on the scals the scals say one at a time. or no elephant alowd.’ That most of the children think Albert should get a haircut is a nice touch too. And Johnson is not so po-faced that he can’t poke fun at his pretensions towards a non-fiction novel: ‘Albert defecates only once during the whole of this book: what sort of a paradigm of the truth is that?’

If you have heard anything about B.S. Johnson before forgiving my fib and continuing to read the scrawl that is now before you, you were probably told that he liked to do strange things with the pages of his books. The Unfortunates, for instance, comes in a box so that you can read the chapters between the first and the last in any order you choose. Albert Angelo is similarly notorious for having a hole cut into a few of its pages, so that you can peer through and read the pages ahead. This is fun, but it’s hardly the most innovative or interesting thing about the novel. It makes nowhere near as much of a difference as the switching between persons and the dual-columns. But for any ‘London kids’ who might be reading the book today, the holes in the page confer a particular advantage: they make Albert Angelo completely incompatible with Kindles, Kobos and iPads. It has to be read in its paper form. Why should you care? Because it means that when you are, like Albert, facing down the disenchanting slog to work and dodging all those clueless non-Londoners on the tube, you can, thanks to the garish yellow spine and bright blue and purple cover of Picador’s new edition, advertise this novel to your fellow commuters as you giggle and gasp your way through its perforated pages, and hopefully make Albert Angelo a book that is widely read, shared, and loved. Just don’t call it fiction.

Andy Wimbush is a writing a PhD on the novels of Samuel Beckett at Darwin College, University of Cambridge.

Percy Circus, ‘leaning like a practised seaman’

‘The first thing you see about Percy Circus is that it stands most of the way up a hill, sideways, leaning upright against the slope like a practised seaman. And then the next thing is that half of it is not there. …’

Very early on in Albert Angelo, B.S. Johnson introduces the reader to Percy Circus, where Albert lives in a ground-floor south-facing flat in no. 29. It’s described in loving detail, as befits a would-be architect:

Very early on in Albert Angelo, B.S. Johnson introduces the reader to Percy Circus, where Albert lives in a ground-floor south-facing flat in no. 29. It’s described in loving detail, as befits a would-be architect:

‘There is stucco channelled jointing up to the bottom of the first-floor windows, which have liitle cast-iron balconies swelling enceintly. Each house is subtly different in its detail from each of its neighbours. The paintwork is everywhere brown and old and peeling.’

Not any longer. In the past half-century, Percy Circus has prospered – the early Victorian houses now go for up to £3 million. It’s on the edges of Amwell, an elegant, rather hidden away locality within ten minutes walk of both King’s Cross and The Angel. And yes, the first thing a passer-by notices is the lop-sided angle at which the Circus leans.

B.S. Johnson knew the area well – in the late 1960s he lived in a flat close at hand in Myddelton Square. A socialist such as Johnson would would have relished the area’s left-wing connections – and in the novel, passing mention is made of the blue plaque for Lenin who once stayed at no. 16, in the side of the Circus demolished by war time bombs and later clearances.

Percy Circus was built in the 1840s and early 1850s by several different developers – hence the variations in design that Johnson mentions. ‘Uniquely complex’, in the judgement of the Survey of London, ‘it has five unevenly spaced entry points, and is laid out on the side of a steep hill’, and it has been described (by Christopher Hussey in 1939) as ‘one of the most delightful bits of town planning in London’.

Percy Circus, Great Percy Street and the ‘Percy Arms’ (alas now closed) all took their name from Robert Percy Smith, a Governor of the New River Company, which once was a major local landowner.

Initially smart town houses, by the early years of the twentieth century the area had fallen into disrepair, as reflected in Arnold Bennett’s Riceyman Steps (1923), which is set nearby.

Towards the close of Albert Angelo, Johnson muses on the manner in which Percy Circus is reflected in Albert’s life and more widely:

Towards the close of Albert Angelo, Johnson muses on the manner in which Percy Circus is reflected in Albert’s life and more widely:

‘there were some pretty parallels to be drawn between built-on-the-skew, tatty half-complete, comically-called Percy Circus, and Albert, and London, and England, and the human condition.’

Andy Wimbush & Andrew Whitehead

References and Further Reading

The B. S. Johnson Society has been established to to ‘honour the life and work of Bryan Stanley Johnson (1933-1973)’ – http://bsjohnson.org/

The British Film Insititute has released Your Human Like the Rest of Them: the films of B.S. Johnson

Percy Circus is covered in the Survey of London vol XLVII: Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, published in 2008.

All rights to the text remain with the author.