Suneel Mehmi

NOTE: This article contains no spoilers – so you can read it and then turn to the novel.

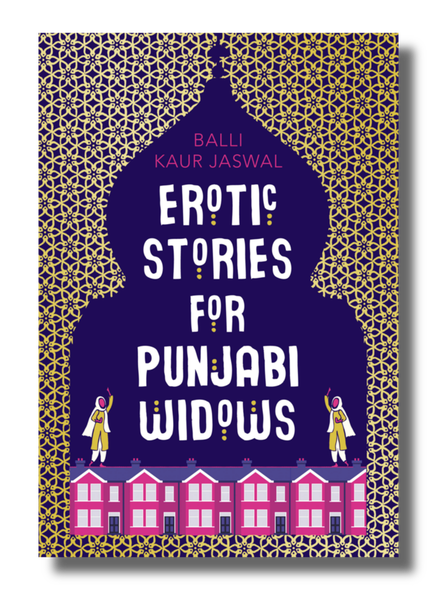

Balli Kaur Jaswal, who is of Punjabi descent, is a prize-winning and critically acclaimed novelist from Singapore. Her novels have been translated into film before and Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows is no exception: Ridley Scott’s production company, Scott Free Productions, and Film Four in the UK have acquired the rights to the book.

Jaswal’s novels regularly feature British-Indian women and in Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows, which follows the trend, there is also focus on London and the Punjabi community in Southall. Indeed, the novel could be seen to address Southall’s invisibility to the non-Punjabi community. As the main character imagines herself saying: “Some people don’t even know about this place […] Let’s change that.”

While Jaswal’s Southall is fictional, and in many ways very contrived, she actually found the inspiration for her novel during a stay in the place where she experienced real conflicting feelings and demands on her as a young Punjabi woman. As she writes,

Southall was such a fascinating place where traditions were preserved and community bonds formed an integral infrastructure of support for migrants. I found it so welcoming, this Indian enclave in England where the customs were familiar to me. But as a modern young woman, I felt stifled as well. Each time I visited, I was torn between wishing I could stay and also being relieved to return to my simpler and less complicated life in East Anglia. I remember standing outside the Southall train station on the first day of summer wearing a short denim skirt and a man shouting at me from his car and pointing to my bare legs and then at the temple in the distance. I began wondering about the drawbacks of community for the people who don’t always benefit from its cultural parameters.

The novel could be read as an investigation of that ambiguous or contradictory homeliness and uncanniness of Southall, particularly as it is seen through the eyes of a young Punjabi woman who was born outside Punjab (the Indian word is a Non-Resident Indian or NRI).

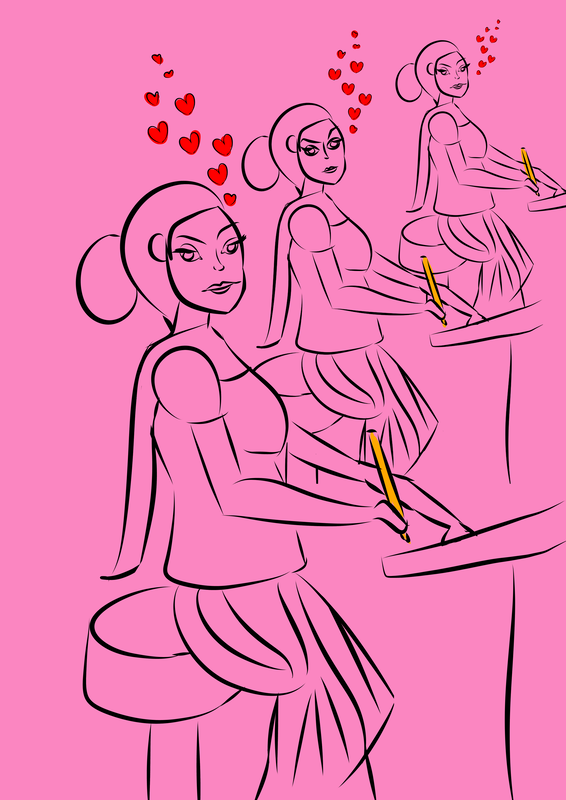

Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows is a coming of age story with strong elements of comedy and which also incorporates aspects of a detective novel, a thriller and, of course, erotica. Major themes include notions of feminism, conservatism, marriage, independence and choice. The plot is simple. The main character, Nikki, a “Fem Fighter” who dropped out of her law degree and lives apart from her widowed Punjabi mother and traditionalist sister, is stuck in a job as a barmaid. One day, she travels to Southall gurdwara (a Sikh temple) to post an arranged marriage advert for her sister on the community noticeboard. While there, she spots a job advert for what appears to be a creative writing teacher for women in the community centre. The role appeals to Nikki’s “Fem Fighter” sympathies because it allows women to express themselves. Nikki applies for the job and gets it but is surprised when her widowed students insist on writing erotic stories after they find an erotic novel in Nikki’s handbag which she got as a joke to provoke her sister.

Nikki becomes immersed in Punjabi life and soon finds out through her students and colleagues the dark secrets of a community in which Jaswal imagines a culture of fear, intimidation and blackmail. As the novel progresses, Nikki (translated as “little one”) grows up, and finds love and a vocation.

The novel is a whimsical flight of fancy. There is probably nothing less socially likely than a Punjabi widow sharing erotic stories with other Punjabi widows. However, the flight of fancy is presented as a triumphant political fantasy. The articulation and expression of women’s sexuality and therefore women’s desires lead to social revolution across London and a destruction of the forces of conservatism. After all, as a character remarks: “These storytelling sessions are good fun but I think I’ve also learned to speak up for what I want. Exactly what I want.” The stories are passed around all over the city and are shown as radically transforming the lives and realities of British Punjabi women, as well as their husbands and the men in the community.

It is emphasised that the Punjabi widows who tell their stories of desire are “outsiders” to the London community, that they are “invisible”. As Nikki reflects towards the end of the novel –

What people wanted from London was all here – the lush green gardens, the majestic domes and church spires, the black cabs busily circling. It was regal and mysterious; she could understand anybody’s impatience to be part of it. She was reminded of the widows. They would have known little of this London before their journey to this country, and upon their arrival, they would have known even less. Britain equalled a better life and they would have clung to this knowledge even as this life confounded and remained foreign. Every day in this new country would have been an exercise in forgiveness.

As those who have been marginalised and who have finally found the means to express their individuality and community, women become the face of radical difference, a transforming and revolutionary presence against the forces of conservatism. Some of the women also have London opened up to them through the storytelling sessions, the freedom to ‘plot the routes they might take them through this vast, magnificent city’.

One of thethemes of the novel is the influence of Western feminism and its practicality. This is elaborated in how Nikki the Western feminist, an outsider to the conservative British Punjabi community, is confronted with the real women’s problems of that community outside of theoretical constructs and learns how to serve that community in reality, rather than in theory. Again, the way in which the British Punjabi women react to, negotiate and even adopt Nikki’s perspectives for the community illustrates how Western feminism can be of influence. Many of the British Punjabi women in the novel, after all, are initially scathingly critical of Western feminists. As one character says: “those British-born Indian girls who hollered publicly about women’s rights were such a self-indulgent lot.” Western feminism is seen to promote the concepts of anti-social selfishness and egocentrism thought to be inherent in Western concepts of individuality. The way in which Nikki wins the confidence of her students and colleagues is therefore of interest because it shows how Western feminism can persuade or form a compromise with traditionalist Punjabi community values.

I have a sceptic’s perspective on the novel. The political fantasy is certainly appealing and modelled on the way that shared fictions in culture and society bring together communities through stories about the politics, the law and notions of citizenship, individuality and gender. However, the charges of selfishness and egocentrism made against Nikki the “Fem Fighter”, the Western feminist, linger. Does Nikki really learn to serve her community, or is she imposing values and perspectives on that community which are calculated to destroy a different way of life and culture in her own interest? Why is the conservative Punjabi community singled out as one that is rife with crime and disorder? A related question could be why is Nikki obsessed with the journals and sketchbooks of Beatrix Potter, an upper-class white woman, whose mind she wants to be “inside”, if she cares about Punjabi women so much? I even wonder at the supposed feminism of this character. While Nikki begins as a facilitator of creative writing for a women’s group, she is led to questions of social justice and the law.

Who in the novel expected her to be a lawyer? Her father. Nikki, arguably, is following a patriarchal programme: the desire of her father. Indeed, her movement towards the law could be seen as a literal illustration of a woman that follows the desires and will of a man that is in a position of authority over her. In addition, I wonder how politically transformative are the articulated desires of a marginalised group of Punjabi women? Even in the novel, such desires don’t move out of the Punjabi community. How effective are such desires in changing the political climate of Great Britain and London itself, an environment that is shown as being racist and unwelcoming to Punjabi life in a novel where some Londoner’s thoughts on Southall and its community are stated as ‘village people who built another Punjab in London’?

Having stated what I feel are both the strengths and my personal reservations about the novel, the question is, what is my ultimate conclusion about this novel? I am in two minds. On the one hand, there are problems that women face with the forces of conservatism in the British Punjabi community. There are indeed men that aim to control women, and women that aim to control women, and there are a tiny minority of women who live in fear and are intimidated. The novel can be seen to address those issues and it asks for transformation and social justice.

On the other hand, why is it always these kinds of negative stories about our community in print? Where are the positive stories? Couldn’t a feminist piece of work highlight successes as well as areas for improvement? Why does the literary imagination always turn to “dark secrets” and disorder and crime “beneath the surface”? Why are such stories published more than positive stories in Britain? After all, even conservative Punjabi families love, respect and honour their women. Punjabi women in conservative families have been working ever since they came to Britain and have had a great degree of independence and autonomy in the family as well as a large say in decision making.

Of course, the Nikki in the novel is characterised as somewhat paranoid. She is suspicious of the men in her life, including her boss and her lover respectively, even though the truth is something that is different to what she thought it was. I wonder if the novel is not an ironic exposition of a paranoid personality that has been formed in colonial and neo-colonial attitudes towards Indians and immigrants? In any case, the novel is an interesting introduction to how we think about Punjabi women today and the challenges that face them. As always, it is up to the reader to interpret the novel for themselves, with – I suggest – some of my own scepticism of the political fantasy in its pages.

Dr Suneel Mehmi is currently researching the relationship between photography and law in fiction from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1920s. He is a scholar and an amateur writer, poet, singer/songwriter, musician and artist. Suneel lives in East London and holds degrees in Law and English Literature from the London School of Economics, Brunel University and the University of Westminster.

All rights to the text remain with the author.