Katharine Stevenson

Philip turned up his coat collar and stood for some minutes in the archway of a court. The place was full of children, swarming about in the gloom, dodging each other, falling over; uttering weird shrieks, like seagulls in a cave. Errand boys, standing astride their bicycles, jeered at stout, prematurely developed girls in coats with cheap fur collars. Their imitation silk calves showed whitely; the heel screwing, as if unconscious. The rain wasn’t going to stop.

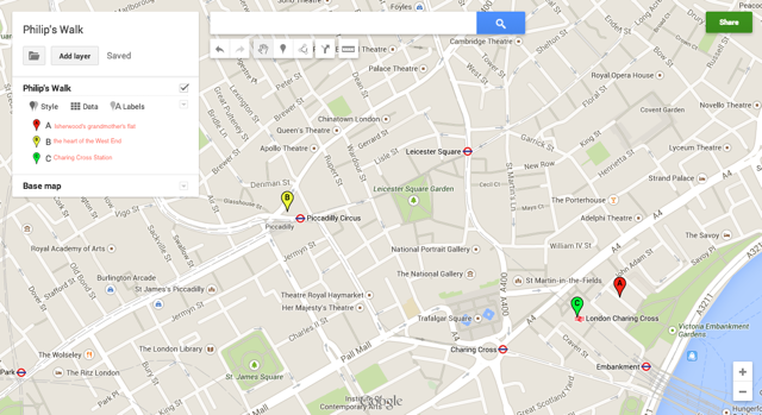

Philip Lindsay, the privileged, self-sabotaging, and somewhat autobiographical anti-hero of Christopher Isherwood’s first novel, is lost in London. Hours before he is supposed to embark on a challenging business venture in South Africa, Philip leaves his mother’s home on an adventure that’s more his speed: fleeing his opportunity for independence from his family by wandering through an unfamiliar working-class part of the city. Philip’s harrowing escapade, the climax of the novel, takes him no farther than ‘the narrow streets running down towards the Embankment on either side of Charing Cross station,’ the neighborhood where, in reality, Isherwood’s own grandmother long resided.

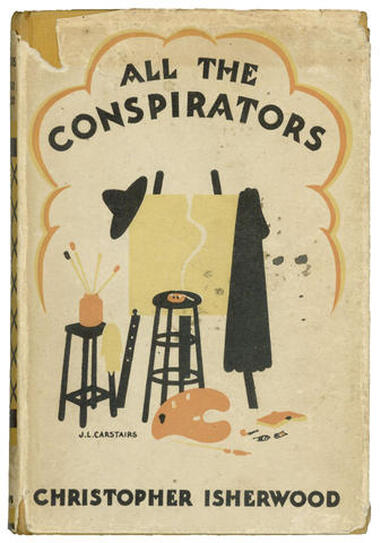

All the Conspirators was first published in 1928 when Isherwood was only twenty-four years old, and was his only work of fiction set primarily in London. This first novel was not a success. In a later fictionalized autobiography, Down There on a Visit (1962), Isherwood describes his experience with his first publication. This segment of Down There on a Visit is set in 1928, when All the Conspirators was published. Isherwood is leaving London to spend time with a friend of the family in Germany for the first time. He writes of himself reflectively in the third person:

He is taking with him on this journey a secret which is like a talisman; it will give him strength as long as he keeps it to himself. Yesterday his first novel was published—and, of all the people he is about to meet, not one of them knows this!

The Isherwood of Down There on a Visit vacillates between believing that his novel will be a smashing success, and worrying himself into believing that it will fail spectacularly. When he gets back to London from Germany, the truth is revealed, and the author switches back to the first person, acknowledging his own presence in the narrative:

When I got back to London, I found that my novel was indeed a flop. The reviews were even worse than I had expected. My friends loyally closed ranks against the world in its defense, declaring that a masterpiece had been assassinated by the thugs of mediocrity. But I didn’t really care. My head was full of my new novel and a crazy new scheme I had of becoming a medical student. And always, in the background, was Berlin.

Berlin proved a great distraction for Isherwood in his brief and only half-serious pursuit of medicine, but it also proved to be his greatest inspiration for writing subsequent novels. Most readers will know Isherwood’s name from The Berlin Stories (1945), which were adapted into the stage play I Am a Camera (1951) and the Broadway musical Cabaret (1966), all set in Berlin. His later novel A Single Man (1964), set in Los Angeles, was adapted into a feature film in 2009. All of these works are partially autobiographical, as are most of Isherwood’s works, and All the Conspirators is no exception. It covers several months in the life of a young man of Isherwood’s generation, who struggles, in rather stereotypical fashion, to find himself while hampered by a privileged upbringing, a doting mother, and an impressive set of neuroses and weaknesses. The title refers to Philip’s family and friends who seem to be leagued in a conspiracy to make him an artistic failure and to keep him an invalid in his mother’s home. One possible exception is Philip’s friend Allen, whose attempts to get Philip out of his comfort zone are always thwarted. However, the reader quickly comes to realize that Philip actually wants to live a life of boredom and comfort; he is too cowardly to take his chances in the real world.

The themes explored in All the Conspirators are also covered in Isherwood’s first slightly fictionalized—perhaps ‘elaborated’ is a good descriptor—autobiography published ten years later, Lions and Shadows (1938). In Lions and Shadows, Isherwood describes his own youth at preparatory school, at Cambridge, and in the few years after he purposefully failed his Tripos exam and got sent down from the University. Two themes are especially visible in both works: thwarted masculinity, and the desire to become some sort of ideal ‘artist’. In Lions and Shadows, Isherwood misses the chance to prove his masculinity in the Great War, and in All the Conspirators Philip misses the chance to prove his masculinity at school—he is kept home because of a supposed heart condition. Describing ‘Leonard Merrows’, the character who would become ‘Philip Lindsay’ in All the Conspirators, Isherwood writes in Lions and Shadows:

The themes explored in All the Conspirators are also covered in Isherwood’s first slightly fictionalized—perhaps ‘elaborated’ is a good descriptor—autobiography published ten years later, Lions and Shadows (1938). In Lions and Shadows, Isherwood describes his own youth at preparatory school, at Cambridge, and in the few years after he purposefully failed his Tripos exam and got sent down from the University. Two themes are especially visible in both works: thwarted masculinity, and the desire to become some sort of ideal ‘artist’. In Lions and Shadows, Isherwood misses the chance to prove his masculinity in the Great War, and in All the Conspirators Philip misses the chance to prove his masculinity at school—he is kept home because of a supposed heart condition. Describing ‘Leonard Merrows’, the character who would become ‘Philip Lindsay’ in All the Conspirators, Isherwood writes in Lions and Shadows:

He is due to enter his public school, ‘Rugtonstead,’ in 1919. Then, quite suddenly, he gets rheumatic fever and is ill for several months. The doctor says his heart has been strained. ‘Rugtonstead’ is out of the question. Leonard must stay at home and have a private tutor. His disappointment and despair know no bounds… he even comes to have a sneaking feeling of relief that he didn’t go to ‘Rugtonstead’ after all: it is so comfortable at home, and then perhaps he would have been a failure! Thus it was that ‘War’ dodged the censor and insinuated itself into my book, disguised as ‘Rugtonstead’/ an English public school.

Similarly, while Philip in All the Conspirators struggles to mold himself into a proficient painter primarily by imitating the stereotypical characteristics he associates with artists, Isherwood describes forcing himself through the same process in Lions and Shadows:

… my prestige, my whole claim to be ‘a writer,’ was at stake. So I plodded on encouraging myself by daily additions to [my] journal; all of which went to build up the new day-dream self-portrait of Isherwood the Artist. Isherwood the artist was an austere ascetic, cut off from the outside world, in voluntary exile, a recluse. Even his best friends did not altogether understand.

The image of the ‘Artist’ doesn’t stick either for Philip or for Isherwood himself. Philip actually cares little about painting and is incapable of concentrating on it; he wants the status of the Artist without any of the actual work

In an introduction to All the Conspirators published many years after the original novel, Isherwood expressesite s his own and Philip’s difficulties with The Past—which includes both War and Family—very articulately:

The Angry Young Man of my generation was angry with the Family and its official representatives; he called them hypocrites, he challenged the truth of what they taught. he declared that a Freudian revolution had taken place of which they were trying to remain unaware. He accused them of reactionary dullness, snobbery, complacency, apathy.

Philip, as we will see, desperately longs to break free from his mother’s influence and his family’s expectations, but is incapable of surviving on his own because of how he has been raised. He longs for independence, but has none of the mental and emotional tools with which to achieve it. This reflects Isherwood’s own feelings towards The Past, and especially towards his mother, with whom he had a close but fraught relationship for most of his life.

All the Conspirators opens not in London but on the coast, where Philip and his best friend Allen Chalmers—a name Isherwood frequently used as a pseudonym for his lifelong friend Edward Upward, to whom the novel is dedicated—are vacationing. It is revealed that just prior to leaving for the beach, Philip has quit his job in the City, procured for him by his anxious mother by calling in favours in his dead father’s name. Here, the reader is introduced to Philip’s current fad, painting, and to the young man Philip comes to think of as his primary antagonist, Victor Page. Allen and Philip encounter Page at their hotel and find that they once attended school with him. Much to Philip’s irritation, Page seems to be everything that Philip is not: suave, decisive, athletic, virile, and, Philip thinks, lacking in the troublesome psychological depth that he and Allen cultivate in themselves. In fact, Philip and Allen conduct themselves rather ignominiously at the beachside hotel, and the neurotic Philip is terribly embarrassed in front of Victor when Allen indulges in an impressive bout of public drunkenness:

There were three people in the lounge. All women. Their figures, seated, bent forward, deeply engrossed in needlework, as the young men came out of the smoking-room. The place appeared to have shrunk slightly smaller, and to be unnaturally quiet. It was as if Philip himself were slightly intoxicated. He could imagine the women’s eyes following them. They steered Allen to the foot of the stairs. Feeling their support, he lolled, sliding his feet. Victor had gone pale, this time. They avoided each other’s glance.

Victor and Philip’s shared experience carrying Allen through their hotel sets the stage for much of the novel’s London action, putting Philip at a social disadvantage in his dealings with Victor when Victor begins courting Philip’s attractive, athletic, and long-suffering sister Joan. Philip already feels himself to be disadvantaged by his lack of an Oxbridge education; like the character Isherwood describes in Lions and Shadows, Philip’s poor health has limited his ability to participate in some of the traditional rites of passage of his sex and class. However, it soon becomes obvious to the reader that it is Allen’s actions, and not Victor’s, that are often carefully calculated to cause the anxious and coddled Philip some healthy discomfort. Unlike Philip and Allen, Victor hates no one, has no ulterior motives, and acts genuinely, characteristics which make him difficult for the neurotic Philip and the manipulative Allen to trust or understand.

Once Philip has tired of painting and he and Allen have begun to annoy one another, the two young men return to their homes in London, where Allen is a medical student and Philip is now at loose ends. Before he can begin his next doomed creative project, he must deal with his mother’s disappointment and nagging about his unemployment. In explaining to his sister his plans to rent a flat as his artistic studio, he unconsciously reveals just how selfish and lacking in perspective he is, the probable reasons why his hard-working and relatively impoverished best friend Allen is often less than kind to him. Philip expects that his mother will pay for him to rent the new flat:

“You mean I’m behaving badly about the cash?”

“Phil, I never said—”

“Well, before you start, please do me the justice to think for a few minutes. People a lot worse off than we are send their sons to the Varsity and keep them there for three or four years. When have I been kept? Why, even at a public school I should have cost more than I did with a tutor. It really is a bit too thick—”

He broke off and began again:

“I admit this is a defeat. I’ve tried the City. I’m no good at it. Very well. But why spend the whole of the rest of my life crying over spilt milk?”

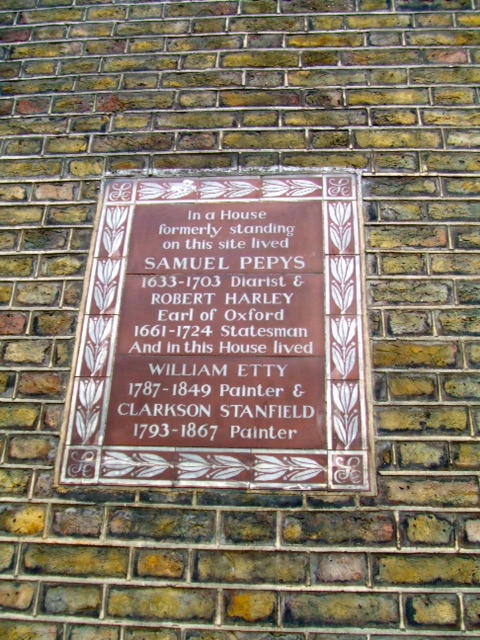

This conversation, which takes place in a cab from Paddington station, concludes when Philip and Joan arrive at their London neighborhood, the fictional Bellingham Gardens. The area does not correspond to the actual Bellingham neighborhood in Lewisham, in south east London; Philip is later able to walk within minutes from his mother’s house to the shops of London’s West End. More likely, Isherwood has based the neighborhood on the area surrounding Buckingham Street and Embankment Gardens, where he visited his grandmother in her flat many times during and after his years at Cambridge in the 1920s. The site of this flat was home to Samuel Pepys long before it was in Isherwood’s family, and was for sale as of summer 2013 when I photographed it.

When the private studio flat is denied him, Philip formulates his grandest plan yet: he will show his mother, show his sister, show Victor, and show Allen that he is capable of independence and success by moving to Africa to become a coffee planter, a job procured for him, again, by a friend of his late father’s. His mother’s reaction is most gratifying:

Currants [Mrs Lindsay’s best friend] bought a map of Equatorial Africa.

“Do you know,” she confessed, “I couldn’t even have told you which coast Philip was going to be nearest to?”

She also remarked: “We shall have to drink lots and lots of coffee, now.”

Mrs. Lindsay and she had both wept when they heard the news of the decision.

“Darling, I do hope you’ll be happy. It’ll be dreadful for us to have to part with you. But I know it’s for your own good. We must try to remember that.”

Allen’s reaction, on the other hand, is more realistic and therefore much less to Philip’s liking. He does not even believe that Philip will go to Africa. Philip visits Allen in his flat, which is in a very different part of London than the upper-middle-class Bellingham Gardens:

Allen’s rooms were in a quiet disreputable street; two stories up. Knock four times. His landlady, a friendly woman in artificial silk jumper and patent leather shoes, opened the door… Half-way up the stairs, one looked into a little glass-roofed verandah or greenhouse; now the kitchen. Washing hung across the doorway on a string. A cistern gurgled from the floor above.

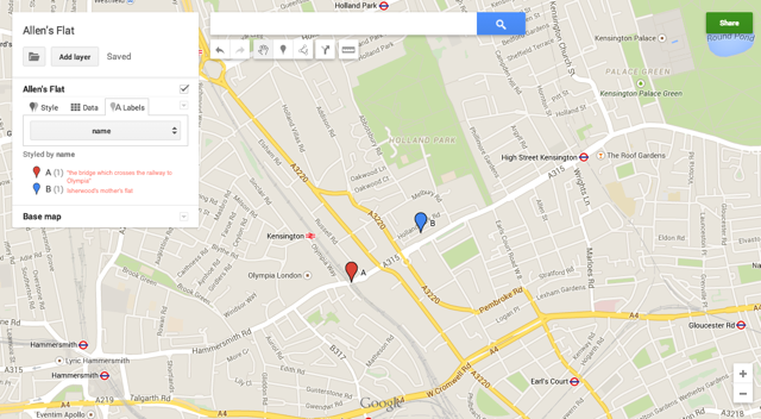

Allen’s lodgings are almost surely based on those of one of Isherwood’s friends described in Lions and Shadows, a medical student named Hector Wintle who appears in the autobiography as ‘Philip Linsley’ and lives

… in North Kensington, away out at the far end of Ladbroke Grove: my home was on the Kensington Road, only a few hundred yards from the bridge which crosses the railway to Olympia. We visited each other regularly, during the Long Vacation, two or three times a week. I liked being with Philip. He was chronically unhappy, and always ready to talk endlessly and amusingly about his troubles. He made me feel wealthy, lucky and successful, as indeed, in comparison with him, I was. Philip was at a crammer’s, preparatory to entering the medical school of a big London hospital. He loathed the crammer’s, loathed chemistry and physics, didn’t want to become a doctor. What he did want was to become a brilliantly successful society novelist and man-about- town, perpetually in full evening dress, surrounded by beautiful and expensive mistresses.

Philip Lindsay of All the Conspirators is obviously a composite character made up of Isherwood himself and several of his close friends from University and post-University days in Cambridge and London.

Allen, of course, is right about Philip’s plans to become a coffee-planter. As the day of his departure from London draws near, Philip begins to panic. On the day he is supposed to depart, he sneaks out of his mother’s house early in the morning:

Hastily, he let himself out into the fog.

He had been running for many minutes when he stopped to draw breath. Turning to the right from the gate, he had followed Bellingham Gardens along its continuation beyond the intersecting thoroughfare, north-eastward. Now he was within a crescent of mid-Victorian buildings; stately, decayed lodging-houses on the edge of the slum district.

Instead of feeling comforted at his escape from the obligation to work on the coffee plantation, Philip feels more and more apprehensive, especially as he begins to encounter Londoners of other classes. The first is a war veteran, almost definitely a nod to the simultaneous guilt, relief, and frustration that Isherwood—and by extension, Philip—felt for having ‘missed’ the Great War:

A man, who has been knocking at the doors of several houses, now came down from a flight of steps opposite and crossed the road with a bundle of papers in his hand.

“Lost yer wy, gov’nor?”

“Oh, no, thanks,” said Philip.

“Jest takin’ a stroll like; for yer ‘elth?”

Philip smiled and nodded. The man began talking, in clipped persuasive Cockney. He wanted to sell one of the printed sheets. It was a poem, written on behalf of ex-service men unemployed…

It appealed directly, naively; from the ex-soldier to the civilian. We have nothing. You have everything.

After guiltily shoving a half-crown into the man’s hand to get rid of him, Philip continues into the West End (see the paragraph at the beginning of this piece). There, in search of a mackintosh, he encounters another Londoner of a different class: a Jew running a pawn shop.

Philip realized that he was holding his leather wallet in his hand. He had pulled it out, with a vague urgency, as soon as he had caught sight of the three golden balls… The sleeves had to be turned back; but, as the young Jew brightly explained, they could so easily be shortened…

“It suits you very well, I think.”

Philip liked him. He paid and went out.

Unlike the war veteran, the young Jew does not tease or judge Philip; in fact, he flatters him, satisfying Philip’s vanity and soothing him after he is shaken up by the panhandler with the poem.

Philip then makes his way towards Piccadilly, deeper into the West End, for a meal. The descriptions of Philip’s view of the other customers are very revealing. Isherwood illuminates Philip’s—and by association, his own—snobbery, and also manages to make it clear how pathetic is this fear and disdain for other classes, born as it is out of ignorance and isolation:

At his table a couple of flash young dagoes, in their Oxfords and high-cut waistcoats, were eating mash on toast and iced cakes… Women with green hats. Men with rings. Sweating as they munched. The band blared triumph. Theirs. Anthropoid. Survival of the Unfittest.

The reader might be reminded of the scene in James Joyce’s Ulysses when Bloom enters a Dublin dining hall, is disgusted by the animalistic men eating meat there, and opts instead for a vegetarian cheese sandwich in a quiet pub. This is probably not an accident; Isherwood was feeling Joyce’s influence strongly when he wrote All the Conspirators, as Ulysses was published while he was at Cambridge. Isherwood commented in an introduction to All the Conspirators in 1958 that the novel is marked by his ‘attempts at a James Joyce thought-stream.’

After his meal in Piccadilly, Philip must find a place to spend the night, and in pursuit of this end he encounters his final lower-class Londoner, the landlady of a cheap hotel. Isherwood’s description of her is particularly vivid:

A fat woman, with a prospect of gas-lit hall and staircase behind her, eyed his bedraggled figure coldly, but admitted that she had a bed to spare. She called shrilly for a consumptive-looking manservant whom Philip followed thankfully up flights of rickety stairs to a bedroom, a tiny garret under the roof. The fat woman, who had bolted the front door, mounted after them. She was crudely and absurdly made up with rouge, eyebrow pencil, and lip-stick. Her pink silk blouse reeked of mixed perspiration and cheap scent. She disliked Philip’s appearance and showed it plainly, but her expression softened when he readily agreed to pay in advance.

The landlady clearly stands in opposition to Philip’s thin, wheedling, manipulative, upper-middle-class mother, whose person and home are always just so.

Philip spends a nightmarish night in the rented bedroom, literally working himself into a fever as he wonders what he should do the next day. He decides that he should go to Sussex, then perhaps France. He wonders whether his family will send the police in search of him once they discover that he is missing, whether the ports will be watched, whether he needs a passport to continue his escape. By morning, he is completely physically ill, his nerves having exacerbated the bad heart he has suffered from since childhood. He leaves the hotel to wander along the Embankment. Philip’s ultimate impotence and weakness are spectacularly epitomized when, just as he begins to contemplate suicide, he collapses helplessly in the very center of London:

Selfridge’s roof-garden was the place. Up to the parapet and it’s over. No, there’s always the instant to consider when you see your balance gone and the pavement and the tops of the cars, and people’s hats.

He looked up at Big Ben for the time. The clock-face was convex, concave. The light withered, went green. Total eclipse. People were bending over him. All talking.

“Where does he live?” asked someone.

“Where do you live?” a man shouted in his ear.

He gave the address.

Despite his condition, Philip gives his mother’s address, sealing his own fate once and for all: When we see Philip again, during a visit from his friend Allen, he is firmly ensconced in his mother’s attic, which has been converted into a studio for his painting. He is more pampered than he has ever been before, carefully tended in his Bath chair by his mother, sister, and his mother’s friend Currants. He is indulged in his every whim and spoken of as if he is a great artist, despite having no actual success. The novel ends with an ironic speech from Philip to the hardworking Allen:

“You see, Allen, what I really dislike about your attitude is that it gets you nowhere. You refuse to venture, that’s what it is. You’re timid. Oh, I grant you one’s got to have the nerve…”

Katharine Stevenson is a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin. Her work focusses on authors who came of age between the world wars and she is particularly interested in queer authorship and fictionalised autobiography.