John Wilson

The Water Gipsies is about a young woman making her life choices. It is also about Hammersmith, the Thames, and the Grand Union Canal … and London Skittles.

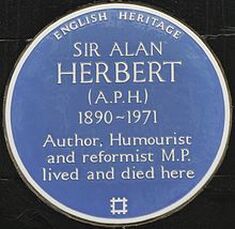

Alan Patrick Herbert loved the Thames and its canals. He was a member of the Thames Conservancy and the first president of the Inland Waterways Association. He was very well-known in his lifetime as a humorist (a Punch staff writer), legal commentator and reformer, and general wit; his authorial voice is that of the highly educated liberal wing of the establishment.

He lived in Hammersmith Terrace, an eighteenth century street close to the river where every house now bears a blue plaque. So he set the greater part of the novel literally on his doorstep. The Hammersmith of the novel is pretty much the real place, between King Street and the river (as it must have been about 1930), although the magnificent picture-house described in chapter five does not seem to correspond to an actual Hammersmith cinema. It is not the famous Hammersmith Odeon, which opened in 1932 as the Gaumont Palace; it’s probably based on one of the several opulent cinemas that were beginning to appear in London at that time.

The story opens on Jane Bell’s twentieth birthday. She lives on a dismasted Thames sailing barge, the Blackbird, on the Hammersmith river shore with her ineffectual father and feckless younger sister, Lily. It’s made explicit that Jane’s world view is due, apart from her own limited experience, to a popular culture that is itself a target of the author’s humour; for example, she is an avid picture-goer, and wishes her life were more like the melodramas she sees twice a week. She habitually thinks of her situation in terms of the caption cards of silent films.

We are told all of Jane’s thoughts and those of the other characters as necessary. The author gives his own opinion directly as well as through the thoughts of Gordon Bryan, a wealthy artist who has a studio on the Hammersmith riverfront. Jane’s thoughts are simple; she never questions her own thoughts. Mr Bryan constantly asks himself why he thinks as he does. This presumably represents their difference in class.

She has two regular boyfriends (with whom she does no more than kiss): Fred is a boatman on the Grand Union Canal, and is as placid as the horse-drawn canal boat on which he lives; Ernest is a station hand on the Underground, an enthusiastic and dogmatic socialist, and as impatient as his motorbike. Jane rather prefers Fred, but feels no passion for either. In the course of the year or so of the story she falls in love with Mr Bryan. He has a somewhat detached and sardonic approach to life, and cares deeply only for his painting and his new sailing boat. His large private income and being a younger son have freed him from necessity and duty: he is in upper-class society but imagines himself not to be of it. When he sees Jane at a disadvantage in his own milieu he berates himself for snobbery. He seems to pretty much embody the author’s attitudes, so when he uses the N-word to himself about a black pianist popular with his smart upper-class friends it suggests that his creator sees nothing wrong with that.

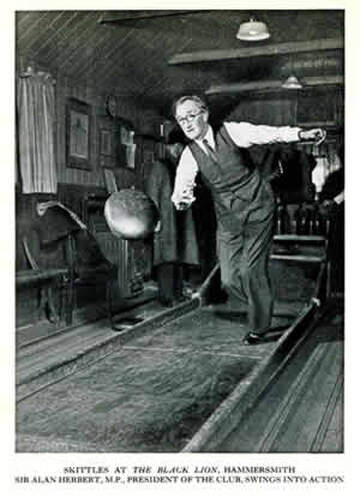

To begin with the story proceeds through a series of strongly visual scenes: Life on the Blackbird and the role of tide and weather; an evening at the Black Swan (the local riverside pub, whose landlady Mrs Higgins is Ernest’s widowed mother); a comic and disastrous expedition to the Derby; visits to a socialist Sunday school and a socialist rally in Hyde Park with Ernest; Jane gathering driftwood for fuel in her small boat;a trip up the Grand Union Canal (the “Cut”) from Brentford on Fred’s family’s boats (named Prudence and Adventure); Lily’s visit to White City greyhound stadium; a skittles match at the Black Swan against a visiting team from another pub.

Herbert was evidently a strong defender of pubs like the fictional Black Swan, which may have been under threat from over-zealous licensing authorities. His description of the pub and its regulars makes Orwell’s idealised Moon Under Water look a bit rough, and certainly won’t have done him any harm in his own local, The Black Lion in Hammersmith.

The description of the canal trip and the life of the boat people is particularly lyrical. Travelling north from Brentford Lock, the canalside is represented as a stretch of almost arcadian peace within London. Much of the canal runs between fields: the novel was published shortly before the arterial roads and new underground lines brought modern industries and housing to this part of West London.

The milieu of the greyhound stadium (an innovation when the novel was written) is described in some detail through Lily’s visits to the dogs. She meets a charming and apparently well-off young Jewish gambler, Mr Moss, whose inside knowledge enables him to successfully predict most of the winners, and Lily ends the evening well ahead. After a subsequent visit he takes Lily for a night in a luxurious hotel. The purpose of this episode in the story is that it implants in Jane a deep desire for a similar experience, so that she can never settle down until she too has luxuriated in a palatial bathroom. If we’ve read Alexander Baron’s The Lowlife we might assume that Mr Moss is one of Harryboy Boas’s breed of compulsive gamblers on a winning streak – living large while he’s in funds, but he’ll soon be skint again. But Moss turns out to be the son of a successful businessman, and he and Lily keep on winning every time they go to the track. Harryboy tells us this is impossible, and I’ll believe Alexander Baron over APH on this one.

Jane’s story speeds up in the second half. After unwilling sex with Ernest she marries him on a false pregnancy scare, and is bitterly disappointed in the hotel they go to for their honeymoon, with its squalid shared bathroom. Ernest and Jane set up home on the Blackbird; Mr Bell has gone to live with his sister in Liverpool and Lily soon goes to live with Mr Moss. Ernest is idealistic and usually tries to do the right thing, but nobody cares for him much, not even his mother. He suspects that Jane doesn’t love him and that she loves Mr Bryan, in both of which he is correct. Nonetheless he becomes reluctantly friendly with Bryan, and coaches him at skittles, at which he is the local champion.

The climax begins with a remarkable piece of sports fiction. Due to handicapping, Bryan and Ernest, the reigning champion, are the contestants in the final of the Black Swan’s individual skittles championship. A cheese-by-cheese (that’s the heavy object they throw) account of the match makes it quite gripping, while the two men’s personal rivalry and a storm on the river rise along with the tension of the match. Bryan wins. This helps to heighten Ernest’s jealous fury, which ends with his attempting to grab Jane on the deck of the Blackbird. She fends him off, he falls overboard in the storm and is drowned.

With Ernest out of the way, as soon as Jane is out of mourning Bryan takes charge of her life for a short spell. He takes her to the London institutions she has never visited, such as the National Gallery and the Houses of Parliament. Finally he gives her a night in a hotel in a room (by herself) even more luxurious than the room Lily shared with her Mr Moss. He also takes her to a party of his arty upper-class friends in Bloomsbury. She hates it, which isn’t what he intended, but this cures another of her yearnings – for a glamorous life. Bryan is fond of Jane but can never love her. He finally escapes from Jane and from his society girlfriend Fay by just sailing away from Hammersmith to circumnavigate Great Britain. Jane longed to accompany him on this voyage but regretfully accepts that it is impossible.

Bryan’s attitude to class and gender permeates his reflections. When he refuses an affair with Jane, he reflects on why he is doing so. “He respected Jane, and he respected himself; and, more, he respected Fred and Mr Green and Mrs Higgins and the Pewters and all the Skittles Club, and their decent respectable standards of behaviour. They had welcomed him, and trusted him, accepted him as one of themselves, though he belonged to a suspected class…. And now, to amuse himself with one of their girls and then throw her aside – what a come down!”

Jane is settled for life in three pages. She marries Fred at Whitsun, and they honeymoon by mooring the Prudence in a corner of the canal Fred has picked out, which “Fred had often thought was pretty and quite like the country, though Ealing and the underground were not far away”. Jane is content. “It was a good life too – travelling up and down, seeing the country, sleeping in the open almost: a better life, she thought, than going to parties with people like Mr. Danty, that Beryl – and Fay. Not so good, perhaps, as sailing round England – but there, that was over and done with.”

John Wilson is a lifelong enthusiast for London the city and for London in literature, art and film. He came to London to study Physics at Imperial College and has lived in various parts of the city ever since.

The Hammersmith Riverside today

Hammersmith riverfront hasn’t changed all that much in appearance. Across the river, the waterworks Jane saw from the deck of the Blackbird has gone. The character of the area has changed, partly no doubt as a result of being cut off from the Hammersmith hinterland by the A4.

APH’s old house on Hammersmith Terrace is marked by a blue plaque. These riverfront houses used to be part of an upper-middle-class enclave, now pretty much the whole area has that character. The riverside trades have closed down or moved upstream.

APH’s old house on Hammersmith Terrace is marked by a blue plaque. These riverfront houses used to be part of an upper-middle-class enclave, now pretty much the whole area has that character. The riverside trades have closed down or moved upstream.

The creek where Fred’s boats lay was filled in before the war. Chiswick Eyot, a very low-lying island composed of soft mud, is mentioned in the book a few times but not described. In 1930 it extended further downstream, towards the main setting of the novel, than it does now – the lower part of it has been washed away.

The riverfront has become much more of a leisure destination than APH describes. A slightly annoying feature is that river wall has a pointed top, so you can’t sit on it or rest a drink on it. The wall looks new, but it annoys Jane in the novel. In The Water Gipsies, living on a boat was the recourse of the poor. Now it’s a middle-class option, and a mooring at Hammersmith is highly desirable. Some of the houseboats are former canal boats like Fred and Jane’s with the cargo space converted to cabins.

The country around the Grand Union Canal in West London has changed drastically (officially most of this stretch is the River Brent, but nobody calls it anything but “the canal”). This is where modern, electric-powered London expanded, filling the fields with houses for both workers in the new industries and commuters on the new underground lines.

The canal itself continued, of course, with its banks a leisure resort for the new residents. From about 1960 the canal has become almost entirely devoted to cruising and houseboats ; Fred and Jane would have been the last generation of “water gypsies”.

References and Links

A.P. Herbert, APH: his life and times, Heinemann, 1970

“The traditional pub game of London Skittles is about to be revived at the Black Lion” (includes a picture of APH playing) http://nnet-server.com/server/common/revblacklion001.htm

London Skittles at the Freemasons Arms in 2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8w957lDsRi8

All rights to the text remain with the author.