John Lucas

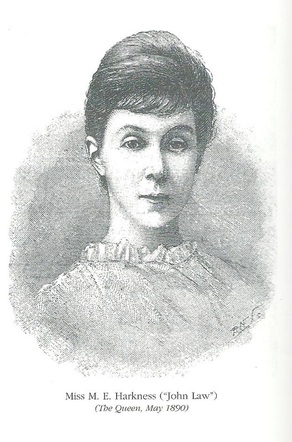

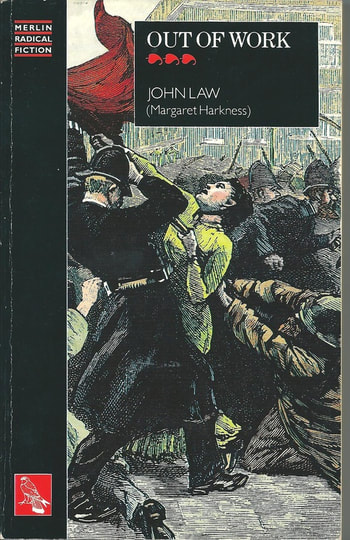

Margaret Harkness is a novelist who, despite the best efforts of scholars, remains something of a mystery. I am not, however, going to say much about her life, beyond the fact that at the time she wrote Out of Work she was clearly involved in and sympathetic to socialist ideas. The novel, which was published in 1888, had been preceded by City Girls, 1887, and would be succeeded by In Darkest London, published a year later. Though not a trilogy, all three novels, published under the pseudonym of ‘John Law’, are set in the London of the 1880s, all deal with city life among the poor, and all are sharpened by Harkness’s readiness to engage with issues from a radical perspective, one which is intended to act as a corrective to the interpretations of those same issues provided by those claiming to speak with a kind of enlightened, disinterested authority.

Margaret Harkness is a novelist who, despite the best efforts of scholars, remains something of a mystery. I am not, however, going to say much about her life, beyond the fact that at the time she wrote Out of Work she was clearly involved in and sympathetic to socialist ideas. The novel, which was published in 1888, had been preceded by City Girls, 1887, and would be succeeded by In Darkest London, published a year later. Though not a trilogy, all three novels, published under the pseudonym of ‘John Law’, are set in the London of the 1880s, all deal with city life among the poor, and all are sharpened by Harkness’s readiness to engage with issues from a radical perspective, one which is intended to act as a corrective to the interpretations of those same issues provided by those claiming to speak with a kind of enlightened, disinterested authority.

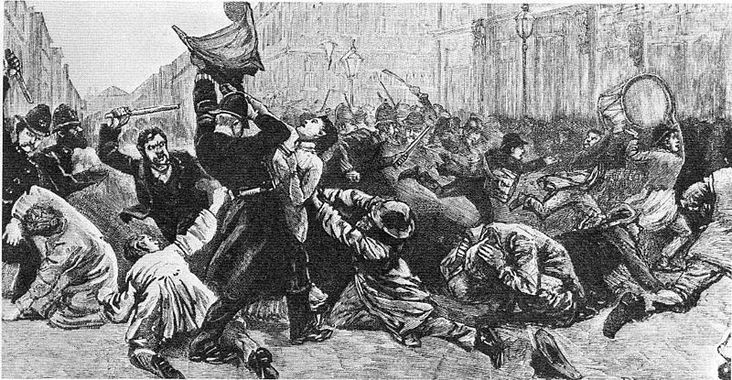

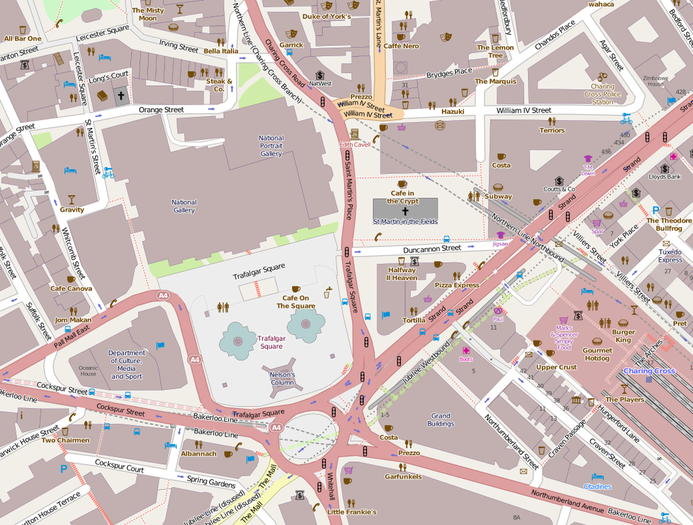

The issues which Out of Work particularly addresses are to do with monarchy, religion and popular protest. And in choosing to focus on the Queen’s Jubilee and the infamous events surrounding 13th November 1887, “Bloody Sunday”, of which more later, Harkness is not only writing to the moment, she is inviting her readers to consider these events from the point of view of working-class men and women. Several other novels dealt with the events of the same year. Among them are George Gissing’s In the Year of Jubilee, written a few years later, as was W.H. Mallock’s The Old Order Changes. These, together with Henry James’s The Princess Casamassima, provide accounts of street protest in which the rioters are seen as an undifferentiated mass whose bestial, mob violence is a threat to society and must therefore be squashed.

Out of Work not only questions this version of protest, its engagement with a number of individuals caught up in the riots challenges the clichés of the “mob”, composed, according to the Times, ‘of all that is weakest, most worthless and most vicious of the slums of a great city.’ Although the novel is in many ways amateurish and, in its depiction of a love affair, deeply conventional, it is also shrewd in its political reading of London life in the late nineteenth-century, and in some respects powerfully radical.

The story on which the novel’s events are strung is simple enough. Jos Corney, a young carpenter, makes his way to the city in search of work which has dried up in his rural birthplace. The lure of the Jubilee helps draw him to London. Surely his skills will be needed to help build the podia and stands that have to be erected across London so that the populace may see and applaud Royal Progresses. But no. Work proves even harder to find in the city, especially for a man with only country skills. At first Jos lodges with Mrs Elwin, a respectable Methodist, where he falls in love with her pretty daughter, Polly, and the pair become affianced. In Everywhere Spoken Against, his study of how Methodism fared in nineteenth-century fiction, Valentine Cunningham rightly protests against the customary dismissal of it as for the most part the religion of the smug, the semi-educated, and the joyless.

Out of Work endorses all these clichés, which is a pity. Harkness’s account of the relationship that develops between Polly and the devout but sexually repellent William Ford is thinly sketched and used as a stick with which to beat non-conformist prejudice. Mrs Elwin is against Methodists marrying into Church – Jos is not only out of work, he is an Anglican. (Harkness rather soft-pedals on Anglicanism, Later, she would be active in the Salvation Army, so she is not an orthodox Marxist, doesn’t think religion per se is the opiate of the people.) Fast forward twenty years to Arnold Bennett’s Anna of the Five Towns for a really substantial, psychologically convincing study of the allure the Methodist, Henry Mynors, holds for Anna Tellwright.

There is nothing to equal Bennett’s subtlety in Anna of the Five Towns. On the other hand, Harkness anticipated Bennett in the way she shows her protagonist involved in work. Indeed, in some respects, she goes further. And even if you say that other publications of the period also look into the world of work, it’s necessary to add that Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor, William Booth’s In Darkest London and Arthur Morrison’s A Child of the Jago – the list could be considerably lengthened – are all by men.

There is nothing to equal Bennett’s subtlety in Anna of the Five Towns. On the other hand, Harkness anticipated Bennett in the way she shows her protagonist involved in work. Indeed, in some respects, she goes further. And even if you say that other publications of the period also look into the world of work, it’s necessary to add that Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor, William Booth’s In Darkest London and Arthur Morrison’s A Child of the Jago – the list could be considerably lengthened – are all by men.

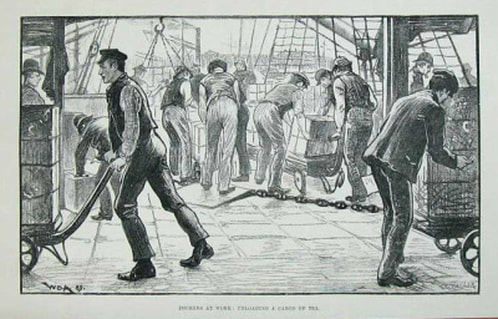

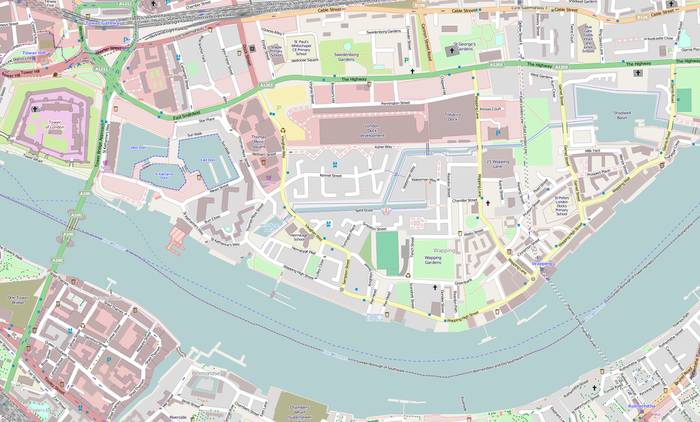

Women were certainly active in socialist politics in the 1880s, but they still didn’t have the vote. They had no voice, no legitimacy. And it may be for this reason that Harkness disguised herself as John Law. As such she is able to follow Jos as he searches for work in the docks, where she writes well of his backbreaking labour at hauling cargoes, she goes with him on the tramp as he walks for miles through the city looking for alternative labour, and writes well of his doss-house experience, where he watches men and women ‘cooking their supper; emptying into tins and saucepans bits of meat, bones, scraps of bread and cold potatoes they had begged, stolen, or picked up during the day. Hungry children held plates ready for the savoury messes, and received blows and kicks from their parents when they came too close to the fire …’.

It is while he is in the doss-house that Jos meets “The Squirrel”. ‘She was scarcely more than a child, a little thing with large dark eyes, and black hair falling about her face.’ A kind of combination of Nell Trent and Little Dorrit, with more than a passing not to Andersen’s Match Girl. The Squirrel is to be read as a figure of disinterested love, a guardian angel, though her ministrations are in vain. She can’t save Jos from sliding into drink, can’t make him turn his thoughts from Polly (even when ‘the pretty Methodist’ jilts him and lets it be known she plans to marry William Ford), and, though the money the Squirrel earns as a flower-seller is enough to get Jos out of prison after he has been unjustly committed for his part in the Trafalgar Square riots, he still doesn’t respond as she hopes he will. He sets off for his birthplace without telling her he’s going, and, hearing of this, she drowns herself in the Thames.

Going with this melodramatic plot are some decidedly awkward moments of narrative intrusion, as when Harkness, who on occasions claims to speak authorial insight into her characters, tells us that Jos’s ‘brains were of the same calibre as the brains of other young carpenters, who had not the intellectual capacity of an educated man’. On others, she denies all knowledge of the inner life of a character she has invented. And so ‘It is impossible to say in what way [the Squirrel] regarded Jos.’

There are also moments when Harkness gives up on being a writer with a writer’s obligation, pre-eminently in her account of the Trafalgar Square riots, where at one point she says that ‘The whole scene was like a nightmare, after reading a chapter of Carlyle’s “French Revolution”’, and at another, that the cell into which Jos is thrown ‘needs a Zola to do it justice.’ The best that can be said of such moments is that they suggest a kind of reporter’s shorthand, as though Harkness has more important things to do than bother with what we might think of as the requirements of fictional realism.

As, indeed, she has. The value of Out of Work lies not so much in any scrupulous attention to detail of the kind we expect to find in the Zola whom she mentions, or the Gissing, whom she doesn’t, but, to repeat a point already made, in her radical refusal to settle for conventional – that is customary, unenquiring – accounts of key issues of the day. This entails her cutting through the flim-flam of those who want to insist that the Monarch is loved and approved by all, and that nobody can be in sympathy with the rioters.

And there is a more radical challenge yet in these contentious positions. It is that the Jubilee and the fact of unemployment may be connected. Chapter 10, ‘Work at the Docks’, records the conversation between dockers on their way to look for work.

“’Ave you ‘eard what we unemployed got to do Jubilee day?” continued the same young man, turning to the others.

“What then?”

“We’ve got to walk two and two down Cheapside afore the Queen; we’ve got to do penance in white sheets and candles; so I’ve read in the newspapers.”

Then the men began to sing:-

“Starving on the Queen’s highway.”

Late in the novel, when Jos has given up hope of finding work in London and is footing it back to the village where he was born and grew up, he overhears some pub talk, in which an old man, dressed like a gamekeeper, complains that “Things aren’t what they were. When I think of all the big nobs who used to come down here shooting in the Prince Consort’s time, I says to myself as there’s something wrong somewhere.” He is alluding to the agricultural depression, which was particularly severe in the 1870s and 1880s. But this isn’t the queen’s fault. “She’s done her best with this Jubilee business.”

This is a good moment. The wife’s understandable anger and frustration at her impoverishment which spills over into the predictable outburst against foreigners is met be her husband’s principled, disinterested socialist convictions, the more courageous as he has to accept his own family’s immiseration.

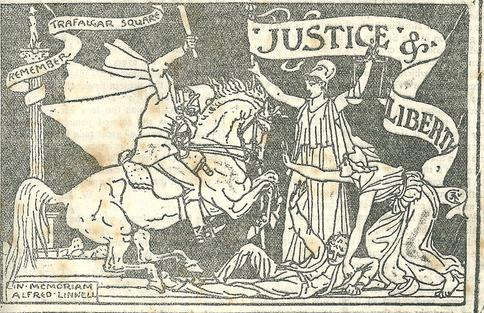

by police in Trafalgar Square at a follow-up demonstration a week after Bloody Sunday

The march of the unemployed to Trafalgar Square was a mass protest at such immiseration. The riots, caused by the police deciding to break up the meeting by charging the square on horseback, resulted in injuries to hundreds and three deaths. According to the Times report to which I have already referred, ‘no honest purpose … animated these howling roughs, it was simply love of disorder, hope of plunder, and the revolt of dull brutality against the rule of law.’

Set that beside Harkness’s account of the day following the queen’s visit to Whitechapel, when ‘ladies had leant back languidly in their coaches, heedless of ragged men, hungry women, and little dirty children … [having] given up an afternoon’s pleasure-hunting in order to gratify the eyes of under-paid men and over-worked women by their shining hats and charming bonnets’, and you have some sense of the novel’s corrective strength, its entirely proper radicalism. And it is of a piece with this radicalism that Jos, returning to his origins in search of work, finds only death. The dream of an innocent, health-giving ‘natural’ world, is merely that – a dream. The year in which Out of Work is set is also the year in which Hardy published The Woodlanders.

John Lucas is a poet, novelist, biographer, literary historian and critic. Recent books include 92 Acharnon Street (2007, paperback 2011), winner of the 2008 Dolman Award for Travel Writing, Things to Say: Poems (2010), Next Year Will be Better: A Memoir of England in the 1950s, (2010, paperback 2011), and a novel Waterdrops, (2011). He runs Shoestring Press.

References and Further Reading

See the entry on Margaret Harkness, In Darkest London for a bibliography of works by and about Harkness

For a full account of the events leading up to ‘Bloody Sunday’, see E.P. Thompson, William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary (1955, revised edition Merlin Press, 1977), and Donald C. Richter, Riotous Victorians, Ohio U.P., 1981

Valentine Cunningham, Everywhere Spoken Against: dissent in the Victorian novel, Clarendon Press, 1975

John Goode, ‘The art of fiction: Walter Besant and Henry James’, in Tradition and Tolerance in Nineteenth Century Fiction, by David Hoard, John Lucas & John Goode, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966

John Lucas, ‘Republican versus Victorian’, in Rethinking Victorian Culture, eds. J. John & A. Jenkins, Macmillan, 200o

For a website devoted to Margaret Harkness: https://theharkives.wordpress.com/margaret-harkness/

Published since this article was written: Margaret Harkness: Writing Social Engagement, 1880-1921, edited by Flore Janssen and Lisa C. Robertson and published by Manchester University Press in 2018

All rights to the text remain with the author.