Flore Janssen

In the recent revival of popular and critical interest in the East End of London, one author who has re-emerged from obscurity is the socialist writer Margaret Harkness. Thanks to Black Apollo Press which reprinted the text in 2003 and again in 2009, her novel In Darkest London is now once more easily available, and gives a comprehensive and unembellished insight into life in Whitechapel in the late 1880s.

In the recent revival of popular and critical interest in the East End of London, one author who has re-emerged from obscurity is the socialist writer Margaret Harkness. Thanks to Black Apollo Press which reprinted the text in 2003 and again in 2009, her novel In Darkest London is now once more easily available, and gives a comprehensive and unembellished insight into life in Whitechapel in the late 1880s.

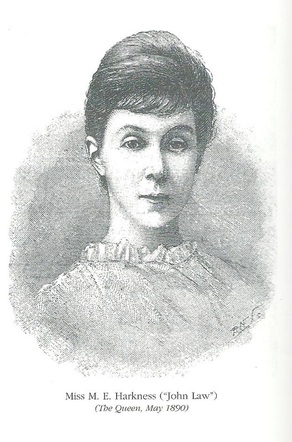

Very little is known about Harkness’s background and personal life. Born in Worcestershire in 1854 as the daughter of a clergyman, she came to London in 1877 to train as a nurse. By the early 1880s, however, she was living in one of the poorest areas of the East End and, disinherited by her father, was surviving on her earnings as a journalist reporting on the conditions of the London poor. This journalistic work had developed into fiction writing by the end of the 1880s. Under the pseudonym John Law, Harkness published five novels on slum conditions, of which In Darkest London was the third.

Then, as now, the East End was emerging as a site of cultural and social interest. In her entry on Harkness in Late Victorian and Edwardian British Novelists, Eileen Sypher explains how –

In the late 1880s and 1890s many British writers turned to London’s East End slums – a late-nineteenth-century metonym for social inequality, as Manchester had been in the mid-century. The East End became the uncharted frontier for many individuals motivated by various philanthropic and revolutionary aims: university graduates, missionaries, statisticians, political organisers, and several independent-minded upper- and middle-class women.

Social historians have not, on the whole, been inclined to take seriously the ministering attentions of those upper- and middle-class ladies whose philanthropic impulses took them into the slums of the symbolic East End. Harkness, however, was not a middle-class domestic creature expanding her sphere of influence to include the deserving but hapless poor: her East End work and her writings on the subject were motivated not only by social concern, but by radical politics.

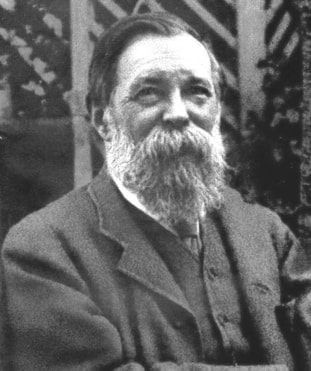

Harkness identified as a socialist throughout her writing career, although the details of her political views were subject to change throughout. She initially belonged to the social circle around Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx’s daughter Eleanor, and was close friends with the latter. The two women played significant roles in the organisation of the London Dock Strike of 1889. Her reasons for quitting this circle are unclear, but she had broken with it by the time In Darkest London was published.

Although the novel references popular socialist ideas of the period, and its characters employ socialist phraseology, In Darkest London is not immediately identifiable as an outright socialist novel. Originally published as Captain Lobe: A story of the Salvation Army, the novel is just that: a description of the work of a Salvation Army captain in Whitechapel, and the characters and situations he encounters. Through Captain Lobe, the reader is allowed glimpses of the Salvation Army headquarters, of slum dwellings and East End street entertainments, of factories and Kentish hop-fields, of the rooms of the ill and the dying, and of the intricacies of Whitechapel streets. Through Captain Lobe, the reader is introduced to the East End bourgeoisie and proletariat, to committed Christians and agnostics, to factory workers and circus performers, to slum lassies and the slum dwellers they are trying to reform.

Binding these scenes together is the rather incidental love story between Captain Lobe and Ruth, the heiress to ‘a small cocoa-nut chip factory’ who, deprived of her inheritance through the evil influence of Mr Pember, the factory foreman and her guardian, wants to escape her plight by joining the Salvation Army. Although he is at first unwilling to acknowledge his affection for the young woman, Captain Lobe, from the beginning, is aware of his strong feelings against Ruth’s joining the Salvation Army and taking on the hard work of a ‘slum lassie’. She is, he tells himself, ‘too young, too delicate!’ Instead, he encourages Ruth to become more aware of the lot of the girls working in her own factory. This leads to a strange friendship between Ruth and the factory’s labour-mistress, Jane Hardy, through which Harkness is able to explore the class relations of the East End, and touch on the role and representation of women in it.

It is clear that most of the characters and situations introduced in this fragmented and episodic novel function primarily to allow Harkness to expose and discuss the social issues they represent. Although, by the time In Darkest London was published, Harkness had broken with Engels and his political group, the novel still reflects the advice Engels gave her after reading her first novel, A City Girl, published in 1887. A successful realist novel, he wrote in a letter dated April 1888, depended not only on ‘truth of detail’, but primarily on ‘the truthful reproduction of typical characters under typical circumstances’. Such realism, which accurately reflects class relations and the position of the proletariat under capitalism, Engels argues, is more effective than ‘a point-blank socialist novel’.

Each of the characters in In Darkest London represents a social ‘type’, and the situations in which the reader sees them are typical situations. As a result, Harkness’s writing may seem less accessible than more canonical Victorian social problem novels, which provide strong and rounded characters to sympathise with and a clear plot to follow. However, her chosen style and characters offer a very thorough summary of the population of Whitechapel in the late 1880s. And in their motivations, convictions and doubts, the characters are still complicated enough to be believable. For instance, Captain Lobe, who is so representative of the committed Salvation Army soldier that other characters often simply address him as ‘Salvation’, suffers from religious uncertainty; and however strong his dedication to his Salvationist cause may be, he still wishes to protect his beloved Ruth from the dangers of the work.

The nameless character whom Harkness dubs ‘the Modern Prometheus’, in a curious reference to Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, is a slum doctor who is afraid to use his medical knowledge, since he knows that his chronically underfed patients’ constitutions cannot withstand any real drugs. The labour mistress who, with her regular attendance of socialist meetings and her outspoken interest in the ‘Woman Question’ could so easily have become a mouthpiece for Harkness’s political convictions, is truthfully depicted as ardent but badly informed and ultimately insecure, through no fault of her own.

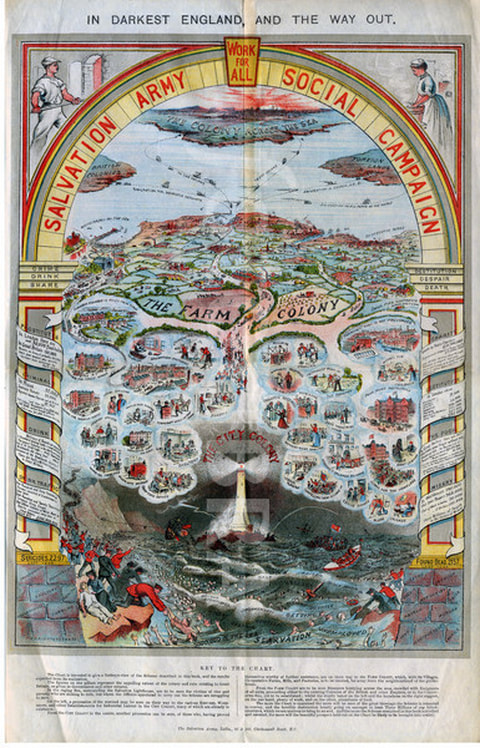

The characters Captain Lobe encounters also give an insight into the social make-up of the late-Victorian East End. In this sense, Harkness is already beginning to break up the commonly accepted dichotomy of East/West as meaning poor (slums)/wealthy. The title In Darkest London – as the novel was renamed when published again in 1891 – is a direct reference to In Darkest England (1890), the influential text published by General William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army. This, in turn, echoed In Darkest Africa (1890), the popular account of Henry Morton Stanley’s exploration of the central African jungle.

By juxtaposing Stanley’s findings with his own in the slums of London, Booth endeavoured to drive home to the comfortably off the reality of life in the slums a stone’s throw from their own homes. Harkness was motivated by a similar desire to show her middle-class readers the horrors of the circumstances in which their near-neighbours lived. As John Goode points out, in Harkness’s fiction ‘[t]he East End is not made exotic […] It is negotiable and determining’ for the characters it produces. Thus, middle-class Ruth, reared in relative material comfort as a member of the East End bourgeoisie, is ultimately unfit for the dangerous, hands-on work of a slum lassie, although she is able, with Jane Hardy as her working-class guide, to engage with the girls who work in her factory and do what little she can, as a young woman who does not yet have influence over her inheritance, to improve their lot.

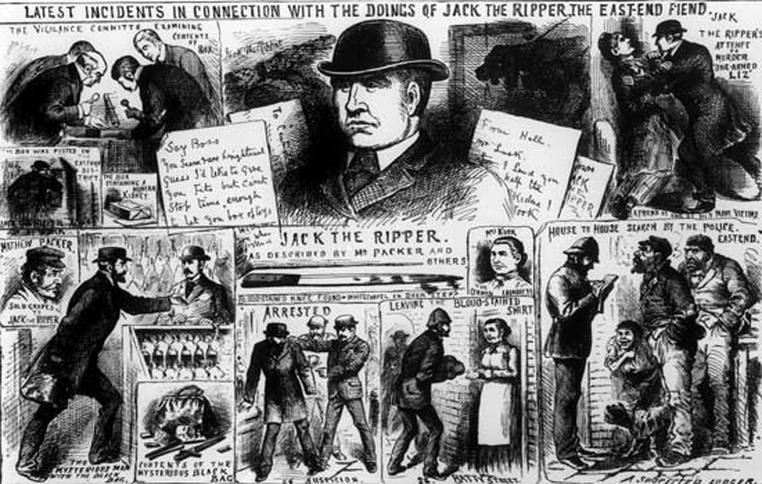

For many modern-day readers, the Whitechapel of the late 1880s is inextricably linked with the image of Jack the Ripper, who murdered his victims between August and November 1888, the year before In Darkest London was published. He makes no appearance in this novel, however: he is not even referred to, because the conditions Harkness describes are horrific enough in themselves, and the Ripper’s atrocities would hardly stand out.

For many modern-day readers, the Whitechapel of the late 1880s is inextricably linked with the image of Jack the Ripper, who murdered his victims between August and November 1888, the year before In Darkest London was published. He makes no appearance in this novel, however: he is not even referred to, because the conditions Harkness describes are horrific enough in themselves, and the Ripper’s atrocities would hardly stand out.

Violence is omnipresent in ‘darkest London’. This is brought home to the innocent Ruth first when the labour mistress takes her to see a ‘penny gaff’ as part of her familiarisation with the ‘environment’ in which her employees live, and later in her association with the slum lassies who deal with (domestic) violence situations on a regular basis. Gruesome waxworks of famous murderers are common entertainments; newspaper boys savour the details of gory murders as they boost their paper sales; domestic and other violence is so common even the slum lassies make few attempts to check it.

Death is commonplace, and relished rather than feared. This is made especially explicit when Captain Lobe is summoned to attend the death bed of a man who confesses to a murder, which he committed out of no further motive than a ‘thirst for blood’. Lobe lets the confession wash over him, and then abruptly leaves the house; no further judgment is made on the dead man or his crime. The only sign that this is in any way shocking is the fact that the next chapter sees a physically and emotionally exhausted Captain Lobe leave London, to embark on the closest thing to a holiday available to him: a trip into the Kentish countryside, joining the slum-dwellers in the seasonal labour of hop-picking.

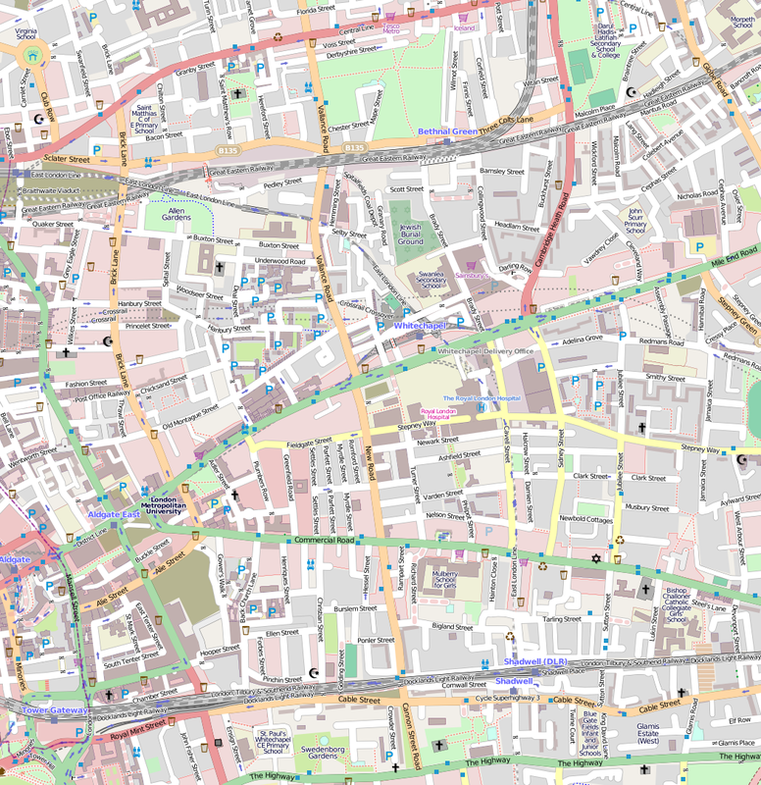

Whitechapel Road

Although a modern-day visitor to Whitechapel Road and the surrounding streets would find it impossible to recognise the warren of slums depicted in Harkness’s novel, references to General Booth and his Salvation Army still abound.

His bust and his statue are placed not far from the Blind Beggar pub, outside which Booth addressed a mission meeting in 1865. His preaching there led to a series of meetings which were the beginning of the East London Christian Mission as an organisation, which would become the Salvation Army.

His bust and his statue are placed not far from the Blind Beggar pub, outside which Booth addressed a mission meeting in 1865. His preaching there led to a series of meetings which were the beginning of the East London Christian Mission as an organisation, which would become the Salvation Army.

A little way down Whitechapel Road, the Salvation Army’s Lifehouse still bears Booth’s name. The wonderful Salvation Army ‘Whitechapel Walkabout’ – www.salvationarmy.org.uk/uki/Whitechapel_Walkabout – marks many key locations of the Salvation Army’s history, including the site of the first Christian Mission and the dancing academy on New Road where the first indoor Christian Mission meeting was held.

The area is still a diverse one, and Whitechapel’s modern-day faith activism takes many different forms. The current Christian Mission is located only around the corner from the meeting house it acquired in 1867. Not far from it on Whitechapel Road is the East London Mosque, and the London Muslim Centre represents an active community presence.

As in Harkness’s day, Whitechapel remains a site of local community activism, which is still driven by active residents, but, fortunately, there is now a much stronger sense of working with and within, rather than on behalf of, the people in the community.

References and Further Reading

Margaret Harkness’s slum fiction – all initially published under the name of ‘John Law’:

A City Girl: a realistic story (1887)

Out of Work (1888)

Captain Lobe: a story of the Salvation Army (1889) – republished in 1891 as In Darkest London, with an introduction by General Booth

A Manchester Shirtmaker: a realistic story of to-day (1890)

George Eastmont: wanderer (1905)

On Harkness, her work and her politics

Entry on Margaret Harkness by Joyce Bellamy and Beate Kaspar in the Dictionary of Labour Biography, vol. 8, (Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1987), pp.103-113

Victorian Web entry on Harkness: Andrzej Diniejko, ‘Margaret Harkness: A Late Victorian New Woman and Social Investigator’, http://www.victorianweb.org/gender/harkness.html

Eileen Sypher, entry on ‘Margaret Harkness (John Law)’, in Late Victorian and Edwardian British Novelists, ed. by G.M. Johnson (Detroit and London: Gale Research, 1999)

Ellen Ross, Slum Travellers: ladies and London poverty, 1860-1920, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), which includes a bibliography relating to Harkness

P.J. Keating, The Working Classes in Victorian Fiction (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1971)

H.G. Klaus, ed., The Rise of Socialist Fiction (Brighton: Harvester Press, 1987), especially the articles by John Goode, ‘Margaret Harkness and the socialist novel’ and by Ingrid von Rosenberg, ‘French naturalism and the English socialist novel: Margaret Harkness and William Edwards Tirebuck’

J. Stoke, Eleanor Marx: Life, work, contacts (Ashgate, 2000), especially Lynne Hapgood’s article ‘Is this friendship?: Eleanor Marx, Margaret Harkness and the idea of socialist community’

Deborah Epstein Nord, Walking the Victorian Streets (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1995)

John Barnes, Socialist Champion: portrait of the gentleman as crusader (Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2006), a biography of the socialist leader H.H. Champion, a close friend and colleague of Margaret Harkness

Friedrich Engels’s letter to Harkness on A City Girl is reprinted in Lee Boxandall et al., Marx and Engels on Literature and Art (New York: International General, 1974)

On social and political slum work

William J. Fishman, East End 1888 (London: Gerald Duckworth & Co, 1987)

Seth Koven, Slumming (Princeton University Press, 2004)

Louise Raw, Striking a Light: The Bryant and May matchwomen and their place in history (London: Continuum, 2009)

Thanks to Lisa Robertson for bringing to our attention what may well be the only likeness of Margaret Harkness, which features at the head of this page.

For a website devoted to Margaret Harkness: https://theharkives.wordpress.com/margaret-harkness/

Published since this article was written: Margaret Harkness: Writing Social Engagement, 1880-1921, edited by Flore Janssen and Lisa C. Robertson and published by Manchester University Press in 2018

All rights to the text remain with the author.