John Lucas

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

‘Waiting for the end, boys, waiting for the end.’ William Empson included ‘Just a Smack at Auden’ in his second collection, The Gathering Storm. The poem, which is not much more than a casual squib, genially disparages the note of premonitory gloom which Empson takes to characterize the MacSpaunday group of poets – Auden, Spender, MacNeice and Day Lewis. ‘Waiting for the end, boys, waiting for the end. / What is there to be or do? / What’s become of me or you … Sitting in cold fears, boys, waiting for the end.’ By the time The Gathering Storm came out, in 1940, Auden was, of course, in America, where the waiting would continue. But for the others the wait was over. The war which all foresaw had begun.

A year later Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square appeared. This remarkable novel, set in the period between the Munich agreement and the declaration of war on September 3rd 1939, focusses on the doings of a group of Londoners who drift from pub to pub, habitually drunk or hungover, shiftless, hollow, enervate, their poisonous lack of care for anyone or anything diluted by the kind of ennui that would have made even St Augustine blink, and who are, though they lack the wit to know it, waiting for the end – not merely theirs but the way of life they lackadaisically embody.

A year later Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square appeared. This remarkable novel, set in the period between the Munich agreement and the declaration of war on September 3rd 1939, focusses on the doings of a group of Londoners who drift from pub to pub, habitually drunk or hungover, shiftless, hollow, enervate, their poisonous lack of care for anyone or anything diluted by the kind of ennui that would have made even St Augustine blink, and who are, though they lack the wit to know it, waiting for the end – not merely theirs but the way of life they lackadaisically embody.

Among them, though not really of them, is George Harvey Bone, a large, melancholy man, whose innate good feelings are made soggy by drink and a hopeless infatuation for Netta Longdon. Netta has film-star good looks and exudes a tawdry glamour which she uses to exploit Bone’s devotion to her in order to get from him what little money he has. She needs the cash in order to buy herself more drink and she needs Bone himself in order to gain an introduction to men he knows, men who may be able to help her in what she occasionally allows herself to think of as her career.

For Netta has an idle fancy that she is an actress. Idle is the right word for it. Netta is beautiful but talentless and she is entirely devoid of commitment, to work, to love, to loyalty. And what is true of her, is true of the others in her circle. Her part-time lover, Peter, is a vicarious ne’er do well – Fascination Fledgeby masquerading as Lord Lucan, we might say – among whose dubious achievements are his wounding a man at a fascist political rally and killing another while driving a car, drunk. Peter wears a polo-neck sweater and sports a small moustache as a ‘uniform’. By such means he tries to single himself out as an ‘ultra-masculine’ man, and like Netta and Mickey, another of her hangers-on, Peter regards the Munich agreement, which we hear of at the beginning of the novel, as providing the licence for a stupendous drinking orgy. ‘They went raving mad, they weren’t sober for a whole week after Munich. – it was just in their line. They liked Hitler, really: they didn’t hate him, anyway. They liked Musso, too. And how they cheered old Umbrella. Oh yes, it was their cup of tea all right, was Munich.’

Bone doesn’t like Hitler. On the other hand, caught in the net of his would-be lover’s graceless charms, without a job – his erstwhile friend and business-partner Bob Barton has taken off for Canada – and lacking much by way of a purpose in life, George Harvey Bone seeks a variety of refuges from an existence he neither wants nor understands. One way out is to believe that the worst – that is, war – might never happen. In this, he is not alone. The novel, which charts with aplomb the calendar from winter through to late summer 1939, shows how with spring may come hope. George’s school friend, Johnnie Littlejohn, a now-successful business man attached to a theatrical agency, whom he encounters by chance and with whom he renews a friendship, allows himself to think as he strolls through Leicester Square on a warm day early in the year, that all is fine:

Fine for the King and Queen in Canada …

Fine for the salvaging of the Thetis …

Fine for the West Indian team …

Fine for the I.R.A. and their cloakrooms …

Fine for Hitler in Czechoslovakia …

Fine for Mr Chamberlain, who believed it was peace in our time – his umbrella a parasol! …

You couldn’t believe that it would ever break, that the bombs had to fall.

This is a good deal subtler than may at first glance seem to be the case. Johnnie’s benign view of even the contemporary disaster of the Thetis (a submarine sunk in the Mersey in which all those on board in fact died) is not so much a way of whistling in the dark as a sudden irrational but understandable surge of optimism. The IRA’s campaign of bombing cloakrooms and postal stores (one went off at Nottingham’s Midland Station) was aimed at property rather than people. Why, even Hitler’s march into Czechoslovakia – that ‘far-off country’ as Chamberlain called it – might be no bad thing if it ended his desire to over-run Europe. And the fact is that many readers coming across this passage in 1941 would be bound to shift uneasily as they digested its implication. For as C.L. Mowat points out in his splendid Britain Between the Wars, 1918-1940, probably a majority of Chamberlain’s countrymen supported his “triumph” at Munich, even if Hitler’s subsequent invasion of Poland caused them to denounce it. From the autumn of 1938 until the spring of 1939, the illusion that there could be Peace in Our Time was still widely shared. Perhaps the end might not come, might be endlessly deferred. Or it may be more accurate to say, most people, especially those with memories of the years 1914-18, fervently hoped that another war might still, somehow, be averted. And who can blame them?

II

Not Bone, certainly. What separates him from his ‘chums’ – as Peter calls the wretched group of soaks and leeches who infest Earl’s Court – is that he actually wants to like people. Bone is a man of peace. And so, having at one point going into a bank in order to cash a cheque, he thinks as he walks up Earl’s Court Road, that the bank clerk with whom he has done business has treated him as an equal, which is certainly not how he is treated by Netta and the rest of her vicious set. ‘He believed that this bank clerk was one of those few, warm-hearted, indiscriminate, easy-going people, who were naturally unaware of any superiority or inferiority in individuals, or who, even if they were aware of such things, were not impressed by, or at all interested in them.’ This belief isn’t put to the test. We never meet the bank clerk again. But it’s of no consequence. Bone’s view of the clerk matters not because it’s a right estimation – for all we know it could be wrong – but because it reveals his own capacity to think well of others, especially as the others he thinks well of have one thing in common: an indifference to ‘any superiority or inferiority in individuals.’ At some instinctive level, Bone is a person whose innate decency is expressive of a democratic impulse. Call it comradeship.

That said, who exactly is George Harvey Bone? Or to put the question differently: why does Hamilton make this amiable, ineffective, insecure, warm-hearted but hapless man the protagonist of his novel? George of England, but apparently no slayer of dragons. This George is more of a Dobbin. In some respects he is quite like George Bowling, the protagonist of ‘George Orwell’s’ almost exact contemporary Coming Up For Air. I put Orwell’s name in quotes merely to remind us that Eric Blair’s choice of pseudonym has surely to be read as a token of his desire to be a kind of spokesman for England. George speaks for itself. And Orwell is the name of a small river that runs into the sea near Southwold, where Eric Blair’s parents retired after years in the Colonial Service. The opening of Hangover Square is set at Hunstanton, Christmas time 1938, where George is staying at the house of an aged aunt. Same sea-coast, though this time Norfolk rather than Suffolk. But neither, surely, much to do with England in the late 1930s.

Which is Hamilton’s point. Or rather, because novels don’t exist to make a point, it’s what we can infer from all that Hamilton shows us. George’s aunt embodies old-style decencies. Her washed-out kindliness is a world away from the rootless, amoral decadence of Hangover Square. Bone belongs to the Square but he is not really of it. At the beginning of the novel we are even told that he would prefer to be a countryman. ‘He wanted a cottage in the country – yes, a good old cottage in the country – and he wanted Netta as his wife. No children, just Netta – and to live with her happily and quietly ever afterwards.’ In your dreams, as the saying goes.

But it was, as it still is, a dream widely shared by his countrymen. In the country, there you feel free. Hunstanton is one version of the dream. Another, to which Bone is reportedly drawn, lies in reaching Maidenhead. There, he keeps reminding himself, he had for a brief period of his childhood been happy, living with a sister now dead, before he was sent away to public school. Maidenhead is his vision of the paradisal place where he can recover innocence and happiness. This is very like George Bowling’s dream of Lower Binfield in Coming Up For Air. And not this novel alone. The yearning away from the corruptions of the city aligns Bone’s dream vision of Maidenhead with a number of novels reaching back at least as far as Our Mutual Friend, and taking in Margaret Harkness’s fine novel Out of Work, and, admittedly more teasingly, Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes. In all these novels – the list could be greatly lengthened – the main characters, trapped in city life, imagine that the rural alternative will guarantee their better health. But for all, disillusionment awaits. You can’t escape history, you can’t escape yourself.

This of course prompts the question, who is “you”? Trying to answer this will lead us to understand just how original a novelist Hamilton is. Much fiction of the 1930s, especially that written from what can be called a radical left-wing perspective, endorses a kind of drab socialist realism. It is manacled to a heavy weight of exact description, of individuals and their circumstances. It’s not so much mass as massy observation. At its best, which is probably Walter Brierley’s Means-Test Man, such observation is redeemed from tedium by an account of particular lives which through sheer accumulation of details gives a sense of the actuality of day-to-day existence. At its worst, it’s a bit like being button-holed by the pub bore determined to tell you in remorseless detail about how he found true love and saved the world.

Bone might be one such bore. He certainly bores Netta. He dreams of inviting her to Brighton for a weekend. Brighton in the 1930s stood for a seedy bohemianism, as it did for long years afterwards. Netta agrees to go, not because she likes Bone but because she needs him to ‘lend’ her money for her rental and other sundries. Bone, poor Bone, is delighted. He goes down to London-on-Sea ahead of her, plays a round of golf while waiting for her to join him – a good golfer – and how Edwardian is that (shades of Sassoon) – he imagines his score of 68 will impress her. He tries not to drink too much and then, sober and wearing his best suit, goes to meet her at the station. She turns up late, escorted by Peter and a drunken hanger-on with whom, as it turns out, she plans to spend the night. Bone protests feebly that he thought she would be coming on her own. ‘”My God,” said Netta. “You didn’t think I could stand you alone, my sweet Bone, did you?” And at this they all laughed.’

It says much for Hamilton’s way of writing that we are likely to feel for Bone’s exquisite embarrassment and hurt at Netta’s treatment of him. It has become a habit for some commentators to suggest that at such a moment Hamilton betrays misogynistic tendencies. This is about as sensible as asserting that Peter is unfairly represented as a fascist sympathizer. No. Peter is a fascist. Netta is a bitch. These people are types. Hamilton writes a kind of black comedy which owes far more to Dickens, and behind him Jonson, than it does to the proponents of literalistic naturalism. Whether he had read Kafka, I don’t know. I doubt it and yet there are connections between Joseph K and George Harvey Bone which allow us to identify both of them as the grotesquely comic victims of forces over which they have no control. In passing, I should note that at about the time Hamilton was writing his novel, Georg Lukacs was championing realism against naturalism by arguing that the former made use of the ‘average’ hero, someone who isn’t a romantic exception but whose very ordinariness makes him available as a model for all. The triumphs of the average hero in surmounting opposition is how society moves forward. Given that nobody in England in the 1930s was familiar with the work of Georg Lukacs, Hamilton is very unlikely to have been aware of the distinction Lukacs made between what was for him realism – which centred on the agency of the average hero – and naturalism, a reactionary form which promoted through its determinism a denial of human agency. Nevertheless, it’s reasonable to see in Bone a version of this ‘average’ hero, though in his case one more wedded to defeat than victory.

Except, that is, for his schizophrenia, ‘Click! … Here it was again. He was walking along the cliff at Hunstanton and it had come again … Click! …’ This is how the novel opens. Bone is, temporarily, out of his mind. Or is he? When his mind goes click, as it does throughout the novel, and with increasing frequency and violence, the shutters come down on his day-to-day glumly polite timidity, his drinking, his irresolution. He knows what he has to do:

He had to kill Netta Longdon…

Why must he kill Netta? Because things had been going on too long, and he must get to Maidenhead and be peaceful and contented again. And why Maidenhead? Because he had been happy there with his sister, Ellen. They had had a splendid fortnight there, and she had died a year or so later. He would go on the river again, and be at peace. … But first of all he had to kill Netta.

In the best sense of the word, Bone’s schizophrenia is a gimmick. (‘A tricky or ingenious device’ O.E.D.) It is Hamilton’s non-naturalistic way of dramatising a split identity, though not, I should emphasise, the kind of doppelganger much favoured in late nineteenth century fiction and typified by Stevenson’s great novel The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. There, light and dark represent what Freud would later come to identify as the opposing forces of Id and Ego. The split that rends Bone is between acquiescence in the intolerable and – Click! – a determination to destroy it. As long as we don’t put too much pressure on the term we can say that Bone represents a type of modern everyman: his liberal decencies immobilise him, much as Liberal western governments found themselves immobilised in 1936 when Franco invaded Spain. But Bone’s other side gives him access to a strength by means of which he can destroy the forces that otherwise will destroy him.

It goes without saying – it should go without saying – that a dystopic vision underlies Hamilton’s novel. His modernist vision of London gives us the city as a quasi-phantasmagoric place of atomistic, separated, even alienated lives. Yes, there can be friendships, even wider alliances; but for the most part, while London may bring people together geographically, grouping them into communities, it separates them emotionally, socially, humanly. The Dantean allusions of Eliot’s Waste Land – ‘I had not thought death had undone so many’ – is implicitly echoed in all of Hamilton’s work.

It is there, for example, in Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, that trilogy which tells from different perspectives three stories about the same individuals, among them a barman, a prostitute, a pub bore, each story showing us the incomprehensions, the misunderstandings, the exploitation of offered love and friendship, which characterise the rootless population of Fitzrovia. As with the Earl’s Court of Hangover Square this is a society without a true sense of mutuality. There is a telling moment in Our Mutual Friend when Bradley Headstone meets Rogue Riderhood and thinks “Here is an instrument. Can I use it?” Many of the protagonists of Hamilton’s novels think the same way. ‘Chums’ are to be (ab)used and discarded, the charivari of pub talk and apparently inconsequential chatter contains a ground-bass of contempt, loathing, and of disgust directed both outwards and inwards. In such a society there can only be victors and victims.

Or is this too glib, too reductive an account of Hamilton’s presentation of London? History to the defeated may say alas, but cannot help, nor pardon, Auden famously wrote. But not all were defeated, not all were immobilised. Some tried to change history. And though by the time Hamilton sat down to write Hangover Square the Republican cause in Spain was clearly lost, the possibility for change remained. Previous philosophers have only interpreted history. The point, however, is to change it. Whether Hamilton was at this time a paid-up member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, I don’t know. I do know, because the writer and Communist Party member Arnold Rattenbury told me, that in the immediate post-war years, he gave money on a regular and generous basis to the Party. And in the way it notionalises change, Hangover Square is surely a Marxist novel. The society it depicts – although ‘evokes’ or even ‘ghosts’ might be the better word for a technique that refuses to stick to the literalistic – is sick almost to death. The denizens of Hangover Square, a place which is as much a state of mind as a physical location, are dying of inanition.

Nor are they alone. There is a brilliant moment in the Seventh of the Ten Parts into which the novel is divided, this one called ‘End of Summer’, where Bone reads a newspaper account of Gracie Fields arriving at Broadcasting House. Under the headline LOOKING EXHAUSTED, the singer tells the waiting crowd that she is delighted to be released from hospital and she offers to sing to them.

Click! …

Click … Here it was again. He was sitting in a damp, stuffy, third-class compartment, reading his newspaper, and it had happened again.

He tried to read on.

She sang, “I Love the Moon …” At the end of her song she said, “Thank you, Mr BBC. Good night and God bless you …” Miss Fields will leave for Capri today. It is expected …

But he couldn’t make sense of the words. He could only think of what had happened in his head.

Poor Gracie Fields. Her illness and her mechanically uttered, vacuous words have the effect of shaking Bone out of his torpor. (I’ve no doubt Hamilton is accurately reporting a newspaper account of this event.) And so – Click! At the fag end of the English summer, 1939, as war comes closer, Bone remembers yet again what he must do. He must kill Netta.

Each of the novel’s Parts carries at least one epigraph. This is the epigraph for the Seventh Part.

They, only set on sport and play,

Unweetingly importuned

Their own destruction to come speedy upon them.

So fond are mortal men,

Fallen into wrath divine,

As their own ruin on themselves invite.

J. Milton. Samson Agonistes.

These lines (1679-1684) are spoken by the Chorus near the end of Milton’s great work, after Samson has pulled down the temple, in the process killing both himself and the Philistines to whom he has for years been hostage, ‘Eyeless in Gaza at the mill with Slaves’. Betrayed into captivity by his passion for Dalilah, he now avenges himself on her and the society she serves. From now on, Hamilton will supply further epigraphs from Milton’s work to each Part of Hangover Square. The Tenth and final Part begins with Samson’s own words to the Philistines he has been summoned to entertain, as reported by the messenger at lines 1640-1645:

… What your commands imposed

I have now performed, as reason was, obeying,

Not without wonder or delight beheld;

Now, of my own accord, such other trial

I mean to show you of my strength yet greater

As with amaze shall strike all who behold.

And in a display of what may be God-given strength he then buries himself and them. This isn’t to say that we should regard Bone as a Miltonic hero. The whole point is that, unlike Samson, Bone is not exceptional. Hamilton’s regard for his protagonist, while genuine, has a sardonic edge to it. To be sure, as Empson would have said, a question hovers over Samson’s final act: was it justifiable or a vain-glorious gesture. Did he save or damn himself? But this isn’t what Hamilton has in mind.

Nevertheless, Bone does kill his enemies. He murders both Peter and Netta and in doing so displays the physical strength that goes, Hamilton suggests, with his golfing prowess. Up until very near the end he has been a slave to Hangoverians, the object of their sadistic taunts, victim of behaviour calculated to humiliate him. But now, he rises up and destroys them. In what seems to me a masterstroke, neither Netta nor Peter is shown protesting overmuch at their deaths. It’s as though, lacking any inner vitality, they are almost content to die. Bone goes round to Netta’s flat at the moment she is about to take a bath. He follows her into the bathroom.

He saw her staring at him, first in surprise, then in terror: he saw that she was trying to speak, but that nothing would come out.

“Don’t bother!” he said. “It’s all right. Don’t be frightened! Don’t bother. Don’t bother!”

He seized hold of her ankles firmly and hauled them up in the air with his great strength, his great golfer’s wrists. Then he grasped both of her legs in one arm, and with the other held her, unstruggling, under water.

Unstruggling! Netta lacks the energy to fight back. And when, soon after, Peter arrives, Bone waits till the man turns his back then picks up his gold club and whacks him ‘just behind his ear where he understood it would kill instantly. Then he went in front of Peter and said, “Are you all right, old boy? I’m sorry. I didn’t hurt you did I? Are you all right?”’ The insouciance of the question seems to give Peter pause, as though he’s considering the courtesy of Bone’s question, but then, like a stage actor in search of a cheap laugh, he simply crashes to the floor. After which Bone takes out some reels of thread and winds them round objects until ‘All the threads were gathered up. The net was complete.’ And while he is doing this, the wireless carries Chamberlain’s announcement of war.

Now may God bless you all. May He defend the right. It is the evil things that we shall be fighting against, bad faith, oppression and persecution – and against them I am certain that the right will prevail.

He turned off that nonsense, and put on his coat.

It’s possible, I suppose, to interpret Bone’s response to Chamberlain’s words as prompted by King Street (the CP headquarters) which, following the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact on 23rd August, took the line that the war against Hitler was an Imperialist one and should be ignored by Marxists. But in his biography, Nigel Jones says that Hamilton never accepted this line and was, for all his Communist sympathies, Churchillian in his patriotism. Not that Jones has anything to say about this moment. My own view is that Bone is understandably irked by Chamberlain’s routine piety. Anyway, by his double murder he has brought speedy destruction on the basically rotten life of which he had for too long been a part and which now requires his own death. For suddenly death is everywhere.

Bone gets to Maidenhead, realises it’s no good, and, with the last of his money, buys a bun and cup of tea in a tea-shop where he studies the newspapers. ‘They were all about the sinking of the Athenia.’ (The Canada-bound Cunard liner was torpedoed by a U boat some 200 miles out into the Atlantic on the very first day of war.) He returns to the digs he’s booked in at, writes a suicide note, turns on the gas and dies early the following morning. Hamilton comments: ‘because of the interest then prevailing in the war [his death] was given very little publicity by the press.’ Average to the last.

John Lucas is a poet, novelist, biographer, literary historian and critic. His books include 92 Acharnon Street (2007, paperback 2011), which won the 2008 Dolman Award for Travel Writing; Things to Say: Poems (2010); Next Year will be Better: a memoir of England in the 1950s (2010, paperback 2011) and a novel, Waterdrops (2011). He runs Shoestring Press.

Searching for Hangover Square – A. W.

‘A story of darkest Earl’s Court’ – the sub-title Patrick Hamilton gave to Hangover Square. It’s a glancing reference to the ‘darkest London’ school of writing about the East End, suggesting that despair at least as great can be found within the superficially much more imposing streets of west London.

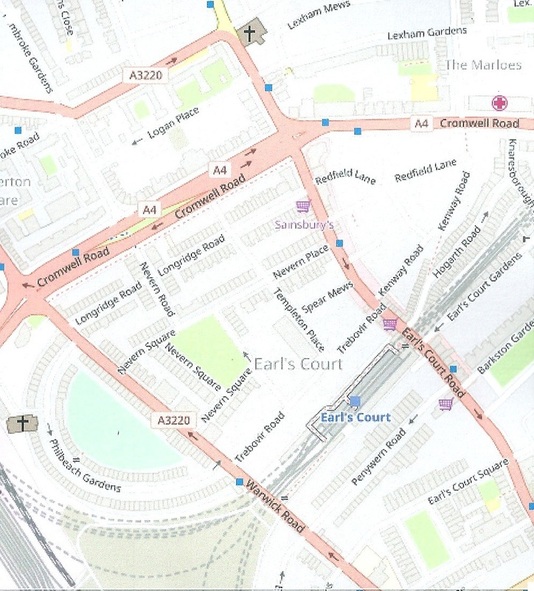

Patrick Hamilton knew Earl’s Court well, and when George Bone saunters up and down Earl’s Court Road, crosses Cromwell Road to see if the lights are on in Netta Longdon’s rooms, and ventures into pubs and cafes by the station, all this would have been familiar ground to the author.

Walks are often plotted with precision – ‘They went past the Post Office and the A.B.C. and then turned down a narrow road on their right …’ – not that Hamilton suggests any affection for ‘the hard, frozen plains of Earl’s Court’. Indeed he conjures up one of the most memorable, miserable, sentences in London fiction: ‘To those whom God has forsaken, is given a gas-fire in Earl’s Court.’

George Bone’s residential hotel – the Fauconberg Hotel, a ‘large, glorified boarding-house’ – harks back to the White House Hotel in Earl’s Court Square, where Hamilton spent a year in his teens while studying at a crammer close by. Hamilton’s sister lived in Earl’s Court, and it was while staying with her in 1932 that he was struck by a car and nearly killed. He was permanently scarred and lost the use of one arm – he later suggested that the incident pushed him towards dependency on alcohol.

George Bone’s residential hotel – the Fauconberg Hotel, a ‘large, glorified boarding-house’ – harks back to the White House Hotel in Earl’s Court Square, where Hamilton spent a year in his teens while studying at a crammer close by. Hamilton’s sister lived in Earl’s Court, and it was while staying with her in 1932 that he was struck by a car and nearly killed. He was permanently scarred and lost the use of one arm – he later suggested that the incident pushed him towards dependency on alcohol.

One of Hamilton’s biographers, Sean French, suggests that the novelist locates Netta’s flat at exactly the spot of his life-changing road accident – at the junction of Logan Place and Earl’s Court Road. Logan Place has been redeveloped, but Lexham Gardens just across the road is largely untouched, terraces of tall late Victorian or Edwardian town houses, now comfortable flats.

After the war, Earl’s Court was home to waves of immigrants – first Poles, later Australians. As befits an area adjoining both Kensington and Chelsea, it’s now more gentrified. But stretches of Earl’s Court Road are still twenty doorbells to the building.

Parts of Warwick Road remain determinedly down-at-heel. Some of the streets running between the two are home to small, at best mid-market, hotels. Now as then, much of Earl’s Court is given over to people living on their own.The transient, largely young population of Earl’s Court has helped the pubs – they keep changing to fit their clientele, but stay in business. There are still five within a three minute stroll of Earl’s Court Station. All would probably have been there in Bone’s time.

Parts of Warwick Road remain determinedly down-at-heel. Some of the streets running between the two are home to small, at best mid-market, hotels. Now as then, much of Earl’s Court is given over to people living on their own.The transient, largely young population of Earl’s Court has helped the pubs – they keep changing to fit their clientele, but stay in business. There are still five within a three minute stroll of Earl’s Court Station. All would probably have been there in Bone’s time.

Although a lot of Hangover Square takes place in Earl’s Court bars, only two are named. The Rockingham ‘opposite Earl’s Court station’, where Bone first falls in with Netta and her crowd, is the Courtfield. The Black Hart is the gang’s main local drinking spot – not located more precisely that ‘near the station’, but by implication not far from Netta’s furnished rooms. The Earl’s Court Tavern is the best fit. An unnamed pub where Bone drinks with his old friend Johnnie Littlejohn can be matched with more confidence. It’s described as a small pub on a narrow road leading indirectly from Earl’s Court Road to Cromwell Road. That sounds like the King’s Head on Hogarth Place, the most comfortable of contemporary Earl’s Court’s drinking holes.

The square of the title is not a place, of course, but a condition. “What’s the matter – our old friend Hangover Square?”

References and Further Reading – J. L.

Other especially relevant novels by Hamilton are: Impromptu in Moribundia, first published more or less the day war was declared and then lost to sight until Trent Editions re-issued it in 1999, with an introduction and notes by Peter Widdowson.

The Slaves of Solitude, Constable, 1947, reprinted 1972, later reprinted by Penguin. A brilliant, scabrous account of wartime England, using much the same technique as that employed in Hangover Square.

There are several biographies of Hamilton, including a peevish one by his brother and a grossly obtuse one by Sean French. The shilling life that gives you most of the facts is Nigel Jones, Through a Glass Darkly: The Life of Patrick Hamilton, Abacus, 1991.

Among the critical writings on Hamilton, I recommend especially Peter Widdowson’s essay ‘The Saloon Bar Society: Patrick Hamilton’s Fiction in the 1930s’ in The 1930s: A Challenge to Orthodoxy, ed. John Lucas, Harvester Press, 1978, and ‘Literature, lying and sober truth: attitudes to the work of Patrick Hamilton and Sylvia Townsend Warner’, by Arnold Rattenbury, in Writing and Radicalism, ed. John Lucas, Longman, 1996.

There are a good many histories of the inter-war years and, in particular, the 1930s, to choose from, but I still think the fullest, most reliable, and best ordered, is C.L. Mowat’s Britain Between the Wars, 1918-1940, Methuen (revised edn.) 1968. And although I can’t bring myself to share Andy Croft’s enthusiasm for some of the novelists of the 1930s he writes about in Red Letter Days: British Fiction of the 1930s, Lawrence & Wishart, 1990, his comprehensive, generous account of the fiction of that decade makes his book essential reading.

All rights to the text remain with the author.