Nicolas Tredell

Graham Greene’s novel The Ministry of Fear (1943) is set largely in London during the Blitz and vividly conveys the death, danger, damage and the ongoing daily life of a capital subjected to constant attack from the air.

As Arthur Rowe, its pursued and pursuing protagonist, moves across London from north to south and east to west, the novel evokes a ravaged city that comes across as a potent, painful material actuality but also as a phantasmagoria: a place where the predictable and the improbable, waking consciousness and dream, the real and the surreal mix and merge; at one point Rowe feels ‘directed, controlled, moulded, by some agency with a surrealist imagination’.

As Arthur Rowe, its pursued and pursuing protagonist, moves across London from north to south and east to west, the novel evokes a ravaged city that comes across as a potent, painful material actuality but also as a phantasmagoria: a place where the predictable and the improbable, waking consciousness and dream, the real and the surreal mix and merge; at one point Rowe feels ‘directed, controlled, moulded, by some agency with a surrealist imagination’.

It is as if the bombs that have flattened buildings have also razed walls in the mind, toppled the thin partitions that divide sanity from madness. The shattered city echoes and amplifies Arthur Rowe’s shattered psyche.

A sense of fear pervades the novel, produced both by aerial bombing and by a sense that the Germans may have blackmailed or otherwise manipulated people in England to work covertly for them and against the British war effort. One of the characters (known only as Johns) explains its title as follows:

The Germans are wonderfully thorough […] Card-indexed all the so-called leaders, Socialites, diplomats, politicians, labour leaders, priests – and then presented the ultimatum. Everything forgiven and forgotten, or the Public Prosecutor. It wouldn’t surprise me if they’d done the same thing over here. They formed, you know, a kind of Ministry of Fear – with the most efficient under-secretaries. It isn’t only that they get a hold on certain people. It’s the general atmosphere they spread, so you can’t depend on a soul.

The title of The Ministry of Fear also alludes to William Wordsworth’s poetry. Robert Hoskins argues that it is ‘a deliberate echo of Book I of The Prelude, specifically of numerous passages in which Wordsworth delineates the formative influence of Nature as a beneficent teacher whose ‘ministries’ of beauty and fear interact with the imagination to produce the poetic mind’. The ‘ministry of fear’ in Greene’s novel, with its wartime London setting, is brutal and urban rather than benign and bucolic: but it does have its moments of beauty even in the midst of destruction and it does, in a sense, minister to Rowe, teaching him, painfully, a way to rebuild himself.

The Ministry of Fear is a third-person narrative largely focused through Rowe’s consciousness but often offering a more articulate and general commentary than he would himself be likely to provide, at least in his current psychological condition. He is a middle-aged former journalist who suffers from an overwhelming sense of pity that led him to administer a lethal dose of hyoscine to his terminally ill wife, Alice. He told the police what he had done and fully expected to be tried, convicted of murder and hanged; but the court took a lenient view and he was sent to a secure asylum from which he has now been set free.

The press called his act a ‘mercy killing’ but Rowe thinks of himself unequivocally and repeatedly as ‘a murderer’. Unlike key protagonists of other mid-twentieth-century Greene novels – Pinkie Brown in Brighton Rock (1938), the whisky priest in The Power and the Glory (1940), Henry Scobie in The Heart of the Matter (1948) – Rowe is not a Catholic; he appears to have been brought up as an Anglican but now seems to have no religious faith, but he is unable to accept a humanist exculpation of euthanasia.

Rowe’s record also means that he is unable to ease his sense of guilt by taking an active part in the war effort, even in civil defence, although he would have been willing to do so. He has private means, an income of £400 a year, which enables him, at that time, to live in moderate comfort, but he is aimless and alone, apart from his tentative, troubled relationship with Anna Hilfe, who, like her brother Willi, is apparently an Austrian refugee living and working in London – but this is a novel in which people and organizations are often not what they seem.

We can see Rowe as an example of an existential hero or anti-hero akin to the protagonists of Jean-Paul Sartre’s La Nausée [Nausea] (1938) or Albert Camus’s L’Étranger [The Outsider] (1942), even though existentialism, as a philosophy, would not be popularized until after World War Two. But if, on one level, The Ministry of Fear is a philosophical novel, like those of Sartre and Camus, on another it is a taut thriller with many surprising twists and turns and it would offer too many spoilers for those yet to read it to detail its intricate plot; the focus here will be on its evocation of wartime London.

It is significant that the novel opens in Bloomsbury, a place associated, through the Bloomsbury Group, with pacifism (at least in World War One), with élite art and attitudes and with the Modernist writing of Virginia Woolf, all of which, especially the last, Greene’s work, here as elsewhere, challenges. In a way that might seem to measure the Bloomsbury Group’s limits, the area now bears the scars of bombing, with an interior that might have figured in a Vanessa Bell painting ignominiously exposed to public view:

[T]here was a war on – you could tell that too from the untidy gaps between the Bloomsbury houses – a flat fireplace half-way up a wall, like the painted fireplace in a cheap dolls’ house, and lots of mirrors and green wall-papers, and from round a corner of the sunny afternoon the sound of glass being swept up like the lazy noise of the sea on a shingled beach.

The last simile is characteristic of the way Greene, in The Ministry of Fear, highlights the destructive effects of the Blitz by comparisons to peaceful, indeed aesthetically pleasant phenomena. Another example occurs near the end of the first chapter, during an air raid: ‘Three flares came sailing slowly, beautifully, down, clusters of spangles off a Christmas tree’; here is beauty in the midst of destruction.

At the start of the novel Rowe finds, in an unnamed Bloomsbury square, behind railings that have not yet been removed for the ostensible purpose of making munitions, a garden fête (a homophone for ‘fate’, as Bernard Bergonzi points out). In a fashion reminiscent of H. G. Wells’ story ‘The Door in the Wall’ (1911), the fête functions as a time machine to transport him back briefly to childhood and to reinsert the rural in the urban, stirring memories of village vicarage fêtes he attended as a boy in Cambridgeshire. Rowe is even able to win a cake by “guessing” its weight, using the figure unexpectedly vouchsafed to him by a fortune-teller whom he has consulted at the fête and who has mistaken his identity.

The cake, however – or more precisely the unusual ingredient it contains – is an example of what Alfred Hitchcock called a MacGuffin, an object that triggers and sustains a tortuous trail of threatening events. (Despite Greene’s deprecation of Hitchcock’s work in his 1930s film criticism, there are many similarities between the writer and the director.) The idyllic quality of the fête dissolves as it quickly becomes clear that Rowe was not supposed to win the cake; his determination to retain it puts him in mortal danger.

Rowe takes his cake back to his lodgings in Guilford Street (which is still there, running from Russell Square to Gray’s Inn Road). This also bears the marks of aerial attack: ‘A bomb early in the blitz had fallen in the middle of the street and blasted both sides’. Houses vanish each night but Rowe stays on although the blasts have already impacted his accommodation:’There were boards instead of glass in every room, and the doors no longer quite fitted and had to be propped at night’. The next day a new lodger, a small man with huge polio-twisted shoulders, reminiscent of Quilp in Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop (1840), takes tea with him and tries to retrieve the cake.

As they take tea, the enemy planes pursue their ‘steady deadly tenor’, the sirens sound, and an air raid starts. In an echo and variation of George Orwell’s famous first sentence in his essay ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’ (1941) – ‘As I write, highly civilized human beings are flying overhead, trying to kill me’ – the bombers themselves are personified in Greene’s text: ‘”Where are you? Where are you?” its uneven engine-beat pronounced over and over again’. At the end of the chapter, an enemy plane becomes a supernatural, nightmarish creature: ‘yet another raider came up from the south-east muttering to them both like a witch in a child’s dream, “Where are you? Where are you? Where are you?”‘.

A direct hit on Rowe’s house thwarts an attempt on his life but turns his world not just upside down but every which way:

Blast is an odd thing: it is just as likely to have the effect of an embarrassing dream as of man’s serious vengeance on man, landing you naked in the street or exposing you in your bed or on your lavatory seat to the neighbours’ gaze. Rowe’s head was singing; he felt as though he had been walking in his sleep; he was lying in a strange position, in a strange place. He got up and saw an enormous quantity of saucepans all over the floor: something like the twisted engine of an old car turned out to be a refrigerator. He looked up and saw Charles’s Wain heeling over an arm-chair which was poised thirty feet above his head: he looked down and saw the Bay of Naples [a water-colour painting that previously hung on his wall] intact at his feet. He felt as though he were in a strange country without any maps to help him, trying to get his position by the stars.

This sense of disorientation increases as the novel goes on. To try to find out more about the people who are pursuing him, Rowe consults the Orthotex private detective agency ‘at the unravaged end of Chancery Lane’; a private detective agency will also feature in The End of the Affair (1951). His own enquiries lead him to participate in a séance in Campden Hill (one of the ‘gloomy hills of London’ in ‘Burnt Norton’, the first of T. S. Eliot’s prewar and wartime poetic sequence Four Quartets). At the séance, conducted by Mrs Bellairs, the fortune-teller at the fête, Rowe witnesses what looks like a lethal stabbing and finds himself the prime suspect (in an anticipation of Hitchcock’s 1959 film North by Northwest). This resonates with and redoubles his guilt at killing his wife. He becomes a fugitive and goes literally underground, to an air raid shelter in the Tube in South London and Greene evokes in words the kind of scene that is visually familiar today from photographs of the period and Henry Moore’s wartime drawings. Rowe lies on ‘the upper tier of a canvas bunk’ and sleeps and dreams for a time:

He woke up to the dim lurid underground place – somebody had tied a red silk scarf over the bare globe to shield it. All along the walls the bodies lay two deep, while outside the raid rumbled and receded. This was a quiet night: any raid which happened a mile away wasn’t a raid at all. An old man snored across the aisle and at the end of the shelter two lovers lay on a mattress with their hands and knees touching.

In the shelter, Rowe imagines himself holding a conversation with his dead mother and trying to explain his own plight and the war’s effect on London, which are linked together, in an almost Shakespearean fashion, as microcosm and macrocosm. There is also an echo, in the phrase “I know too much”, of Hitchcock’s film The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), the latter part of which is set in London (Hitchcock made another version with the same title in 1956). Rowe is likewise a man who knows too much:

“I’m wanted for a murder I didn’t do. People want to kill me because I know too much. I’m hiding underground, and up above the Germans are methodically smashing London to bits all round me. You remember St Clement’s – the bells of St Clements. They’ve smashed that – St James’s, Piccadilly, the Burlington Arcade, Garland’s Hotel, where we stayed for the pantomime, Maples and John Lewis […].”

The familiarity of most of these names of London churches, streets and retailers reinforces the sense of destruction (and, to a twenty-first century audience, of survival and rebuilding). The least familiar name today is Garland’s Hotel, in Suffolk Street SW1, which was popular with MPs, clergymen and novelists; Anthony Trollope, Henry James and D. H. Lawrence had all stayed there, and perhaps also Greene himself, and he is likely to have known of its literary associations. A bomb destroyed most of the hotel on 8 March 1941; it was hit again and wholly wiped out in the air raid on the night of 17-18 April 1941, and never rebuilt.

The next morning, Rowe has breakfast in a bomb-damaged A.B.C. [Aerated Bread Company] café in Clapham High Street and, with some help from the third-person narrator, reflects on how the timing and distribution of raids has fragmented London’s sense of identity, thus slightly challenging, or at least complicating, the idea of the Blitz as a force that unified the capital:

London was no longer one great city: it was a collection of small towns. People went to Hampstead or St John’s Wood for a quiet week-end, and if you lived in Holborn you hadn’t time between the sirens to visit friends as far away as Kensington. So special characteristics developed, and in Clapham where day raids were frequent there was a hunted look which was absent from Westminster, where the night raids were heavier but the shelters were better.

The novel resumes and develops these reflections as Rowe takes a number 19 bus from Piccadilly to Battersea (as one can still do today) to see a former friend, Henry Wilcox, who he believes may still help him with ready money by cashing a cheque:

Knightsbridge and Sloane Street were not at war, but Chelsea was, and Battersea was in the front line. It was an odd front line that twisted like the track of a hurricane and left patches of peace. Battersea, Holborn, the East End, the front line curled in and out of them … and yet to a casual eye Poplar High Street had hardly known the enemy, and there were pieces of Battersea where the public house stood at the corner with the dairy and the baker beside it, and as far as you could see there were no ruins anywhere.

The sense that Battersea is in the front line, despite its peaceful segments, is reinforced for Rowe when he reaches Henry’s to find that a funeral procession is about to take place for Henry’s wife, an A.R.P. Warden like her husband, who was killed in the course of her duties when a wall collapsed and who will later receive a posthumous medal. Henry feels, however, he should have stopped his wife from undertaking such a dangerous task and this makes him identify with Rowe even in the act that had once made him finally reject his old friend: ‘”I killed my wife too. I could have held her, knocked her down …”‘

Part Two of The Ministry of Fear consists of what at first seems to be an Arcadian interlude well away from London and the war. Death also dwells in this Arcady, however, and soon starts to show the skull beneath the skin. It is a tribute to Greene’s narrative skill that, on a first reading, it takes a little time to work out what is happening and indeed to whom it is happening in these chapters. This section of the novel shows Greene’s ability both to deploy thriller conventions and, despite his rejection of the kind of Modernism represented by Virginia Woolf’s writing, to create, within an apparently lucid narrative, a sense of disorientation akin to that in the high-Modernist fiction of Kafka.

The later part of the novel, which moves between London and what is ostensibly a country clinic for the shell-shocked, includes two urgent journeys through the blitzed capital: both have lethal outcomes but also serve to advance the thriller action, to further Rowe’s psychological reintegration, and to evoke a ravaged but still resilient metropolis. The first journey occurs on the morning after an air raid and takes Rowe by taxi through ‘odd devastated boarded-up London’; he travels along ‘the ruined front of the Strand’; ’round the gutted shell of St Clement Danes’, by ‘the ruins around St Paul’s’ and ‘the obliterated acres of Paternoster Row’, past the Mansion House, and to a city tailors’ shop where a pair of cutting-shears slit short a thin-spun life.

The second journey begins with Rowe crossing Battersea Bridge from south to north on foot and then getting a taxi; it is marked by an atmosphere of hot pursuit and ominous expectation. An A.R.P. warden, Rowe’s taxi driver and a fellow passenger they pick up on the way all utter the phrase ‘Yellow’s up’, to indicate a preliminary warning that enemy bombers are on their way, and the narrator reiterates this: ‘A few people were hurrying home; buses slid quickly past the Request stops; Yellow was up; the saloon bars were crowded’. The taxi takes Rowe across Sloane Square and Knightsbridge, through Hyde Park, along the Bayswater Road and to Praed Street and a blacked-out Paddington Station where, as the air raid the yellow warning promised strikes with full fury, the climactic showdown of the novel takes place in the Gents – a lavatorial location from which Greene succeeds in extracting humour, but in a way that exacerbates rather than eases the narrative tension.

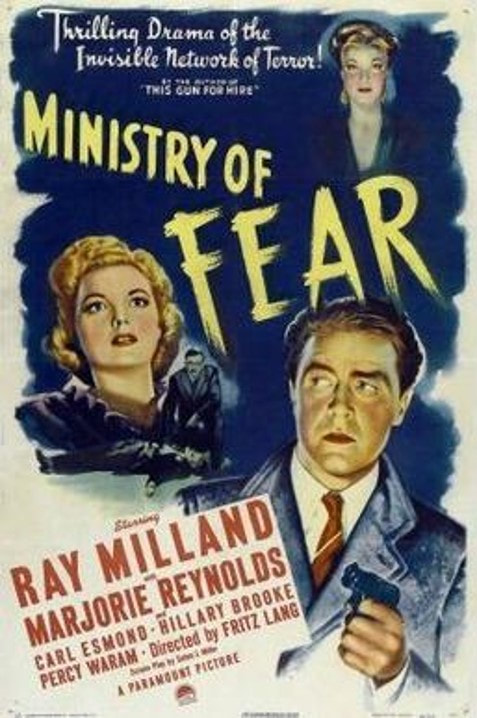

Paramount Pictures quickly made The Ministry of Fear into a movie with the same title which came out in 1944, starring Ray Milland, an American-based actor of Welsh origin who often played English parts, and directed by the Austrian-German Expressionist director who had gone to Hollywood in the 1930s, Fritz Lang. It is a passable film noir but does not try to reproduce the novel’s portrayal of acute disorientation or its evocation of the Blitz (the latter of course was hardly necessary at the time for Londoners and they might well have found it painful; it could also have been seen as potentially morale-sapping for both English and American audiences). A twenty-first century filmmaker, however, might be able to develop these aspects more fully, in audiences now hungry for recreations of World War Two and more used to narrative mystification.

Paramount Pictures quickly made The Ministry of Fear into a movie with the same title which came out in 1944, starring Ray Milland, an American-based actor of Welsh origin who often played English parts, and directed by the Austrian-German Expressionist director who had gone to Hollywood in the 1930s, Fritz Lang. It is a passable film noir but does not try to reproduce the novel’s portrayal of acute disorientation or its evocation of the Blitz (the latter of course was hardly necessary at the time for Londoners and they might well have found it painful; it could also have been seen as potentially morale-sapping for both English and American audiences). A twenty-first century filmmaker, however, might be able to develop these aspects more fully, in audiences now hungry for recreations of World War Two and more used to narrative mystification.

The Ministry of Fear is one of those Greene novels which its author initially categorized as an “entertainment”, implying that it was not on the same level as his “serious” fiction, though he later dropped this division in the Collected Edition of his work. It remains less highly regarded and studied than some of Greene’s other novels such as Brighton Rock, The Power and the Glory and The Heart of the Matter. In A Study in Greene (2006), Bernard Bergonzi, one of Greene’s best informed and most judicious critics, calls it ‘a preposterous story, even allowing for its genre’ and ‘a vehicle for Greene’s obsessions’. In both these respects, we could add, it resembles a Hitchcock film, a further likeness between writer and director.

In the experience of reading The Ministry of Fear, however, the preposterousness recedes into the background of a gripping narrative and the obsessiveness increases its intensity without making it self-absorbed: as Bergonzi acknowledges, it is ‘sharply written and conveys a strong sense of the physical reality and prevailing sensibility of London in the Blitz’. There is also its Modernist aspect, which Bergonzi overlooks: its evocation, within a thriller form, of profound disorientation.

It is interesting to compare The Ministry of Fear with two other novels published (as Bergonzi mentions) in the same year, 1942, and also set in the Blitz – Henry Green’s Caught and James Hanley’s No Directions – and with Greene’s later novel in which a flying bomb attack on London in 1944 plays a pivotal role, The End of the Affair. (This last novel will be the subject of a later London Fictions article.) Certainly The Ministry of Fear, while very entertaining, is more than an “entertainment” in any diminishing sense and merits promotion into the higher rank of Greene’s fiction.

References and Further Reading

Eliot, T. S., ‘Burnt Norton, 1935’ in The Complete Poems and Plays of T. S. Eliot (London: Book Club Associates by arrangement with Faber and Faber, 1977), pp. 171-6

Greene, Graham, The Ministry of Fear ([1943] Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975)

Hoskins, Robert, ‘Greene and Wordsworth: ‘The Ministry of Fear’’, South Atlantic Review, vol. 48, no. 4 (November, 1983), pp. 32-42

Orwell, George, ‘The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius’ (1941) in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell: Volume II: My Country Right or Left 1940-1943, ed. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (Harmondsworth: Penguin in association with Martin Secker & Warburg, 1980), pp. 74-134

Web sources:

Bomb Sight – Mapping the World War 2 London Blitz Bomb Census: http://www.bombsight.org/about/

The Garland Hotel: http://www.westendatwar.org.uk/page_id__231.aspx

West End at War: http://www.westendatwar.org.uk/

Several of the images of bomb damage are taken from the West End at War site. The view from St Paul’s is a Museum of London image credited to Arthur Cross and Fred Tibbs.