Nicolas Tredell

The pivotal moment of Graham Greene’s novel The End of the Affair (1951) occurs in June 1944 when a new form of weapon strikes home: the V-1, the flying bomb that needed no plane or pilot. Greene’s The Ministry of Fear (1943) had vividly evoked London during the Blitz; The End of the Affair mentions the Blitz occasionally but its powerful account of aerial attack focuses on a later phase of World War Two.

The novel unfolds largely in the capital just before, during and just after the war and its metropolitan topography moves mainly between the north side of Clapham Common, where Henry Miles, a senior civil servant, lives with his wife Sarah in a ‘desireless’ marriage, and the south side (socially, at that time, ‘the wrong side’) of the Common where Sarah’s sometime lover Maurice Bendrix, an unmarried novelist, lodges.

The novel unfolds largely in the capital just before, during and just after the war and its metropolitan topography moves mainly between the north side of Clapham Common, where Henry Miles, a senior civil servant, lives with his wife Sarah in a ‘desireless’ marriage, and the south side (socially, at that time, ‘the wrong side’) of the Common where Sarah’s sometime lover Maurice Bendrix, an unmarried novelist, lodges.

In the Clapham area, the novel also takes in the Pontefract Arms, based on the actual and still open Windmill (now a Youngs pub) and St Mary’s Catholic Church in Clapham Park Road. Greene himself lived at 14 Clapham Common North Side from 1935 until bomb damage made him leave in 1940. The house now bears a blue plaque commemorating his residence there.

The itinerary of the novel extends beyond Clapham to include Rules Restaurant and the Roman Catholic Church of Corpus Christi, both in Maiden Lane, which joins Bedford Street to Southampton Row between the Strand and Covent Garden; Vigo Street, which runs between Regent Street and the junction of Burlington Gardens and Savile Row, where Bendrix consults a private detective agency; and Eastbourne Terrace by Paddington Station, where, at that time, small hotels with grand names offered rooms for hire by the hour as well as the night where couples might assuage their carnal desires.

Unusually for a Greene novel, The End of the Affair does not proceed chronologically, as if to model in its form the disorientation of its main narrator: ‘If this book of mine fails to take a straight course, it is because I am lost in a strange region: I have no map’. The imagery here echoes the title of Greene’s 1936 travel book, Journey Without Maps, but now it is London rather than Liberia, and its territory of desire and torment, in which Bendrix is a stranger in a strange land.

The End of the Affair is also unusual for a Greene novel in being a first-person rather than third-person narrative (his previous book, The Third Man (1950) was told in the first person, but this was a novella worked up from his script of the famous 1949 film directed by Carol Reed). Bendrix does most of the storytelling, in Parts One, Two, Four and Five of the novel, but Book Three, crucial to the whole narrative, consists almost wholly of extracts from Sarah’s diary. A major part of the power of the novel comes from the edged energy of its first-person narrations: as Sarah observes in her diary, ‘Maurice’s pain goes into his writing: you can hear the nerves twitch through his sentences. Well, if pain can make a writer, I’m learning, Maurice, too’.

Bendrix – ‘a man known by his surname’ who ‘might never have been christened’ with a forename – first meets Sarah, through her husband Henry, in 1939. In Book One, chapter 3, he recalls ‘the traffic grinding towards Battersea, the gulls coming up from the Thames looking for bread, and the early summer of 1939 glinting on the park where the children sailed their boats – one of those bright condemned pre-war summers’. He goes to a party at Henry’s, whom he has met only the week before, in the course of research for a novel he had begun, but would never finish, in which a senior civil servant was to be the main character. He slips out of the party for a time to walk with Henry on a Clapham Common which is lyrically evoked, a calm oasis before the storm of modern war, recalling childhood and the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries:

The sun was falling flat across the Common and the grass was pale with it. In the distance the houses were the houses in a Victorian print, small and precisely drawn and quiet: only one child cried a long way off. The eighteenth-century church stood like a toy in an island of grass – the toy could be left outside in the dark, in the dry unbreakable weather.

But there is intrigue in this idyll; returning with Henry to his house, Bendrix glimpses, in a mirror, ‘two people separating as though from a kiss’. One of them is Sarah and Bendrix wonders whether Henry knows about it. The kiss signals her promiscuity, which will make Bendrix intensely jealous once he becomes her lover, though he has been promiscuous himself prior to his affair with her.

When Bendrix first takes Sarah out they go to Rules in Maiden Lane – London’s oldest restaurant, founded in 1798, which is still there today. But in The End of the Affair the names of both restaurant and road take on an ironic significance: Rules becomes the place which will catalyse their breaking of the rules, and Sarah is the reverse of an innocent maiden. Moreover, ‘Maiden Lane’ may derive its name from ‘Midden Lane’, a place where dung is deposited, which would symbolize the corruption beneath the illicit passion of the adulterous lovers.

On their way back to the tube afterwards, standing over a grating (it, or its likeness, is still there) by a doorway in Maiden Lane, Bendrix kisses her ‘rather fumblingly’, uncertain at this stage of their relationship why he does so, since he has taken her to lunch only to question her about Henry’s habits for the purposes of his novel, and thinks her too beautiful to be accessible to him. The grating suggests the uncertain ground, fissured with apertures, on which their relationship will uneasily stand and also alludes to the theatrical trapdoor of the Elizabethan stage through which people drop to hell – as both of them will, in an emotional sense.

When Bendrix sees Sarah again a week later, they go to the Warner cinema to see a film adaptation of one of Bendrix’s novels (Henry is averse to the cinema). Bendrix finds the adaptation bad, apart from one scene set in a cheap restaurant where a girl is momentarily reluctant to eat the onions her lover has ordered with her steak because her husband dislikes the smell – an avowal that makes the lover realize, with pain and anger, that she will return that evening to her husband’s arms and lips.

Bendrix and Sarah then go to an expensive restaurant – Rules again – and Sarah, in their conversation, is about to identify the ‘onions’ scene in the film as the one she knows Bendrix has written when the waiter puts a dish of onions on their table; she tells him that Henry can’t bear onions but Bendrix and Sarah both like them. This apparently anti-romantic, unerotic vegetable awakens their mutual passion.

Greene may be alluding humorously here to the image of the ‘vegetable love’ in Andrew Marvell’s seventeenth-century poem ‘To His Coy Mistress’ (1681) – and a further dimension of the joke is that Sarah, who will soon become Bendrix’s mistress, is far from coy and, at this stage, is as eager as her lovers to (in Marvell’s words) ‘tear [her] pleasures with rough strife / Thorough the iron gates of life’:

Is it possible to fall in love over a dish of onions? It seems improbable and yet I could swear it was just then that I fell in love. It wasn’t, of course, simply the onions – it was that sudden sense of an individual woman, of a frankness that was so often later to make me happy and miserable. I put my hand under the cloth and laid it on her knee, and her hand came down and held mine in place. I said, ‘It’s a good steak,’ and heard like poetry her reply, ‘It’s the best I’ve ever eaten.’

‘Onions’ will later become the ‘code word’ in their letters ‘to represent discreetly our passion. Love became “onions”, even the act itself “onions”’. It is a vegetable equivalent of Swann and Odette’s floral image, ‘do a cattleya’, in Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (1913-27).

On this second encounter, Bendrix and Sarah quickly leave Rules – and the rules that forbid adultery – behind, prioritizing consummation over consumption:

There was no pursuit and no seduction. We left half the good steak on our plates and a third of the bottle of claret and came out into Maiden Lane with the same intention in both our minds. At exactly the same spot as before, by the doorway and the grill, we kissed. I said, ‘I’m in love.’

‘Me too.’

Unable to go home, they get a taxi by Charing Cross Station:

I told the driver to take us to Arbuckle Avenue – that was the name they [presumably the cabbies] had given among themselves to Eastbourne Terrace, the row of hotels that used to stand along the side of Paddington Station with luxury names, Ritz, Carlton, and the like. The doors of these hotels were always open and you could get a room any time of day for an hour or two.

The nickname ‘Arbuckle Avenue’ to indicate a street of sexual licence probably refers to the film star ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle who was enmeshed in an early Hollywood scandal, standing trial three times in 1921 and 1922 for rape and murder. Though eventually acquitted, the bad publicity wrecked his career.

Greene also uses the nickname in his earlier novel Stamboul Train (1932) where Amy Peters calls Coral Musker a ‘“tart”’ and asserts: ‘“I know where you belong […] Arbuckle Avenue. Catch ’em straight off the train at Paddington”’. The nickname contrasts ironically with the ultra-respectable connotations of the terrace’s postal name of ‘Eastbourne’. (In the first edition of the novel in 1951, Greene had used the name ‘Leinster Terrace’, which does exist but is about half a mile into Bayswater from Paddington; by the time of the 1975 Collected Edition, however, he had changed it back to its factually accurate name.)

The time-shifts of the novel allow Bendrix to look back on Eastbourne Terrace from a later date: immediately after the passage quoted above, he observes: ‘A week ago I revisited the terrace. Half of it was gone – the half where the hotels used to stand had been blasted to bits, and the place where we made love that night was a patch of air’. Here wartime destruction reinforces the fact that Bendrix’s affair has ended, pulverizing the physical memento of the first consummation of their passion and conveying an almost Shakespearean sense of human transience and insubstantiality in the image of ‘a patch of air’, which recalls Prospero’s words in The Tempest: ‘These our actors, as I foretold you, were all spirits, and are melted into air, into thin air’.

Bendrix pursues his relationship with Sarah for most of the war. A childhood accident has left him with one leg slightly shorter than the other so he is disqualified from joining the Army but takes part in Civil Defence, volunteering for night duty (and gaining ‘a quite false reputation for keenness’) so that he can write – and see Sarah – in the mornings, the only time when she is easily available. The relationship is a tortured one: as in Catullus’s famous poem 85, ‘Odi et amo’, Bendrix hates and loves, but knows one reason for his conflicting passions: his intense jealousy.

The end of the affair occurs in the house where Bendrix lodges on ‘the first night of what were later called the V1s in June 1944’ (historically, this was 13 June). Bendrix points out that, by then, people had grown unused to bombing – the Blitz had ended in 1941 and there had been only a brief recrudescence in February 1944 – so they could not at first grasp what was happening:

When the sirens went and the first robots came over, we assumed that a few planes had broken through our night defence. One felt a sense of grievance when the All Clear had still not sounded after an hour. I remember saying to Sarah, ‘They must have got slack. Too little to do,’ and at that moment, lying in the dark on my bed, we saw our first robot. It passed low across the Common and we took it for a plane on fire and its odd deep bumble for the sound of an engine out of control. A second came and then a third. We changed our minds then about our defences. ‘They are shooting them like pigeons,’ I said, ‘they must be crazy to go on.’ But go on they did, hour after hour, even after the dawn had begun to break, until even we realized that this was something new.

Here Greene uses the term ‘robot’, a word that was only thirty-one years old at the time of the novel’s publication; Karel Čapek had coined the term in his play R.U.R. [standing for ‘Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti’, or, in English, ‘Rossum’s Universal Robots’] (1920), deriving it from the Czech word ‘robota’, meaning ‘forced labour’. It is an unusual word for Greene to use and was associated at the time primarily with the genre of science fiction.

The term ‘robot’ emphasizes the change the V-1s inaugurated in aerial warfare: during the Blitz, George Orwell had begun his essay ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’ (1941) with the sentence ‘As I write, highly civilized human beings are flying overhead, trying to kill me’ and his sentence acknowledged the humanity of his attackers even in their inhumanity, in a way that linked them back to soldiers operating siege engines on ancient battlefields; but now, while ‘highly civilized human beings’ have built and launched the flying bombs, they no longer pilot them: warfare has entered a new and more alienated era.

In the peace after making love, ‘one of the robots crashed down on to the Common and we could hear the glass breaking further down the south side’. Bendrix suggests they should move to the basement but Sarah is reluctant to do so in case his landlady is there; he goes down to check and experiences what would be the distinctive trait of the early V-1s, although not initially recognized as such – they were most dangerous when they went quiet:

As I ran down the stairs I heard the next robot coming over, and then the sudden waiting silence when the engine cut out. We hadn’t yet had time to learn that that was the moment of risk, to get out of the line of glass, to lie flat. I never heard the explosion, and I woke after five seconds or five minutes in a changed world. I thought I was still on my feet and I was puzzled by the darkness: somebody seemed to be pressing a cold fist into my cheek and my mouth was salty with blood.

Bendrix extricates himself from under a door and returns upstairs to Sarah, saying, with Biggles-like sangfroid ‘“That was a close one”’. But Sarah’s response is not quite what he expects:

She turned quickly and stared at me with fear. I hadn’t realized that my dressing gown was torn and dusted all over with plaster; my hair was white with it, and there was blood on my mouth and cheeks. ‘Oh God,’ she said, ‘you’re alive.’

‘You sound disappointed.’

Bendrix only learns the full reason for Sarah’s response eighteen months later, when he reads her diary: she had feared that Bendrix was dead and, despite her apparent lack of any previous religious commitment, prayed to God to let him live, digging her nails into the palms of her hands in an almost saint-like act of self-flagellation. The long last sentence of her diary entry for that day, running to 86 words, drives home the intensity of her feelings:

I said very slowly, I’ll give him up for ever, only let him be alive with a chance, and I pressed and pressed and I could feel the skin break, and I said, People can love without seeing each other, can’t they, they love You all their lives without seeing You, and then he came in at the door, and he was alive, and I thought now the agony of being without him starts, and I wished he was safely back dead again under the door.

Sarah remains true to her vow – and Bendrix finds himself jealous of a God in whom he does not believe.

Eighteen months later, in January 1946, Bendrix encounters Henry on a ‘black wet’ night on Clapham Common and takes him into the public bar of the Pontefract Arms, a new experience for Henry, a transgression of class barriers at a time when the interior divisions of a pub reinforced them; as Bendrix observes, ‘I got the impression that the nearest he had ever before been to a public bar was the chophouse off Northumberland Avenue where he ate lunch with his colleagues from the Ministry’.

Henry, who still has no idea that Bendrix has been Sarah’s lover, confides his concern about his wife and later, when they return to Henry’s house, admits he has considered hiring a private detective agency to check if she is being unfaithful. Then Sarah comes in the front door – Bendrix is quicker than Henry to recognize that it is her step rather than the maid’s – and she reawakens the ‘old disturbance’ in her former lover.

Bendrix decides he himself will consult the private detective agency that has been recommended to Henry – Savage’s at 159 Vigo Street – because he wants to find out whether Sarah has a lover and who he might be. But the inside of the agency surprises him:

It was curiously unlike what you would expect in Vigo Street – it had something of the musty air in the outer office of a solicitor’s, combined with a voguish choice of reading matter in the waiting-room which was more like a dentist’s – there were Harper’s Bazaar and Life and a number of French fashion periodicals […].

There is a Greenian joke here, especially with the reference to ‘reading matter’, in locating the agency in a street associated with two of Greene’s publishers: the Bodley Head, whose founders, John Lane and Elkin Mathews, had published the notorious Yellow Book (1894-7) from an office there, and Penguin Books, which John Lane’s nephew Allen had founded in 1935 at 8 Vigo Street.

A private detective agency also featured in Greene’s earlier novel set in wartime London, The Ministry of Fear, but there the detective assigned to the case was a remote figure, a watcher from a distance who eventually disappears. Mr Parkis, the detective assigned to the case in The End of the Affair, is one of Greene’s most memorable secondary characters, threatening at times to steal the show, with his dignity, his conscientiousness, his errors that mix comedy and pathos, and his love for and pride in his only son, just over twelve years old, whom he has misnamed Lancelot rather than Galahad (not realizing the former’s adulterous reputation until Bendrix cruelly corrects him), whose mother is dead, and whom he is training for the profession (while shielding him from the worst aspects of the cases he pursues).

Parkis’s first error is his report to Bendrix on Sarah’s meeting with a man without realizing (a trick of the half-light) that the man was Bendrix himself who, following their encounter after eighteen months in Henry’s hallway, had asked her out again. Bendrix and Sarah had met in the Café Royal in Regent Street but quickly adjourned to Rules. When they left Rules, Bendrix had again stood on the grating where they first kissed back in 1939, but an ominous cough had seized Sarah and balked any prospect of physical contact.

Parkis does, however, reveal a key item information of which Bendrix was unaware: after Sarah parted from him, she entered a ‘Roman church’ (as Parkis puts it) in Maiden Lane, though to sit rather than to pray (Parkis had followed her inside). This is the Roman Catholic Church of Corpus Christi, which, like Rules, is still there.

Later, it is Parkis who secures Sarah’s diaries for Bendrix to read (from which Bendrix learns of her vow when she thought the flying bomb had killed him), and who thinks he has identified Sarah’s lover – a Richard Smythe who lives at 16 Cedar Road in Clapham.

Smythe, however, turns out to be, not a lover, but an anti-religious rationalist preacher with a handsome but disfigured face whom Sarah has been consulting in the hope that he will help her unbelief by reinforcing it and thus free her from her vow to renounce Bendrix. But Smythe, the providential atheist, has the reverse effect of confirming her faith and, in the process, he falls in love with her.

Sarah’s cough in Maiden Lane is a harbinger of doom. After reading as much as he can bear of her diary, Bendrix phones to say he is coming over to her house to see her – Henry is absent, though he now knows that Bendrix and Sarah were lovers. To avoid Bendrix, Sarah goes out on a sleet-slashed night that will exacerbate her condition to an extent that will soon prove lethal. On that night, Bendrix tracks her down to the Roman Catholic church at the corner of Park Road and tries to persuade her to elope with him; she resists and he finally desists and departs. His hope that they may flee together persists; but eight days later Henry phones to say she is dead.

In the aftermath of her death, Parkis’s son Lance recovers from a potentially fatal appendicitis attack, telling the doctor ‘it was Mrs Miles who came and took away the pain’, and Mr Smythe is cured of his facial disfigurement.

Bendrix stiffens Henry’s resolve that Sarah should be cremated at Golders Green rather than buried, despite pressure from a Catholic priest, Father Crompton; but before the funeral Smythe, now himself advocating Sarah’s interment, says that she had told him in a letter that she had started taking instruction in Catholicism and after the cremation Sarah’s mother reveals that Sarah had been secretly baptized as a Catholic at the age of two even though she was not brought up in the faith.

These two miracle cures mark a distinct shift in genre towards the end of the novel. It is possible to argue that Lance’s recovery is a natural one which he, a motherless boy on the edge of adolescence, understandably attributes to Sarah whom, with his father, he has watched, observed and admired; but in the original edition of the novel, Mr Smythe’s facial disfigurement is a ‘strawberry mark on one cheek’, a vascular birthmark known medically as a haemangioma that may disappear in children but that cannot, in an adult, vanish spontaneously: in other words, its disappearance must count, metaphorically or actually, as a miracle.

Greene toned this down in later editions of the novel, converting the ‘strawberry mark’ to ‘the spots which covered one cheek’ so that their disappearance need not be seen as miraculous: but the sense of a genre shift remains; the reader has entered a world in which miracles may be possible; we are no longer fully in the realm of realistic fiction.

Evelyn Waugh, Greene’s fellow Catholic convert and novelist, approved the miracles, praising what he called the ‘active beneficent supernatural interference’ in the novel and affirming that ‘this defiant assertion of the supernatural is entirely admirable’. But for other readers they may prove a problem as they turn a novel that is in many respects intensely realistic into something else: today it might fall under the rubric of magic realism.

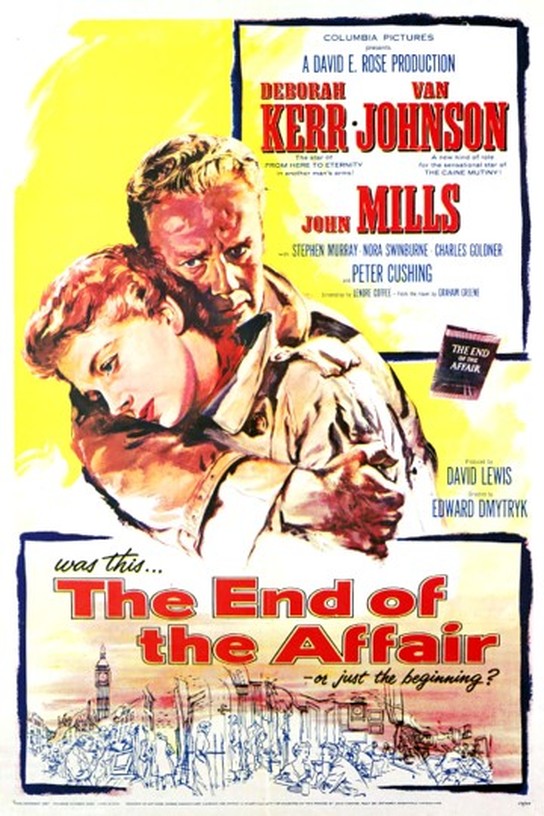

The End of the Affair generated two very good films: the first, in 1955, directed by Edward Dmytryk, with Van Johnson as Bendrix and Deborah Kerr as Sarah, and a peerless performance from John Mills as Parkis, made good use of location settings in London, particularly around the neo-classical Chester Terrace in Regent’s Park.

The End of the Affair generated two very good films: the first, in 1955, directed by Edward Dmytryk, with Van Johnson as Bendrix and Deborah Kerr as Sarah, and a peerless performance from John Mills as Parkis, made good use of location settings in London, particularly around the neo-classical Chester Terrace in Regent’s Park.

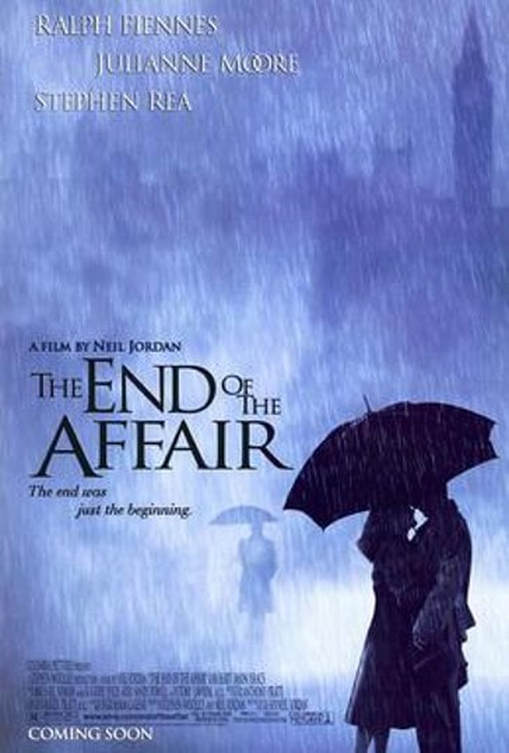

The second, in 1999, directed by Neil Jordan and featuring Ralph Fiennes as Bendrix and Julianne Moore as Sarah, included London locations such as Battersea Park (doing duty for Clapham Common), the Prince Albert in Formosa Road, Maida Vale, Maida Vale tube station, the Priory Church of St Bartholomew the Great in Smithfield, St Mary Magdalene Church in Woodchester Square, W2, Kew Green and Kensal Green Cemetery. Although these locations differ from those in the novel, they emphasize how important London is to its story and atmosphere.

The End of the Affair, however, would be Greene’s last substantial novel set in the capital. In the perspective of his later writing career, it marked the end of his affair, as an author, with London. (His own ill-fated affair with Lady Catherine Walston, which fed into the novel, may have played its part in this.)

The End of the Affair, however, would be Greene’s last substantial novel set in the capital. In the perspective of his later writing career, it marked the end of his affair, as an author, with London. (His own ill-fated affair with Lady Catherine Walston, which fed into the novel, may have played its part in this.)

His postwar reputation was primarily that of a writer who set his major novels in international trouble spots: Vietnam in The Quiet American (1955), the Belgian Congo in A Burnt-Out Case (1960), Haiti in The Comedians (1966), Argentina in The Honorary Consul (1973). But in a global perspective, wartime London was itself an international trouble spot; and The End of the Affair anchors its metaphysical and supernatural elements in a credibly realized city where, through the alchemy of the imagination, the spiritual and secular, the miraculous and the mundane, intersect and interfuse.

References and Further Reading

Greene, Graham, Stamboul Train (London: William Heinemann, 1932)

– – -, The End of the Affair (Melbourne; London; Toronto: William Heinemann, 1951)

– – -, The End of the Affair (London: Penguin, 1975)

Orwell, George, ‘The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius’ (1941) in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell: Volume II: My Country Right or Left 1940-1943, ed. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (Harmondsworth: Penguin in association with Martin Secker & Warburg, 1980), pp. 74-134.

Web Sources

Corpus Christi Catholic Church, History

http://www.corpuschristimaidenlane.org.uk/history/

Croft, Michael A., ‘Arbuckle Avenue, Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene’ (13 August 2008), Stuff I Done Wrote

https://orangeraisin.wordpress.com/archive/arbuckle-avenue/

[I am grateful to John Lynham whose response (18 September 2012) to Michael A. Croft’s posting alerted me to Greene’s use of ‘Arbuckle Avenue’ in Stamboul Train.]

English Heritage, Graham Greene blue plaque in Clapham

http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/GrahamGreene