Jane McChrystal

Stella Gibbons’s Westwood portrays life and manners in Highgate and Hampstead during the Second World War. As a local resident, Gibbons was well-placed to satirise the posturing and pretensions of the artistic types she draws her bead on in the novel. When Westwood was published, Gibbons had already been writing fiction full-time since 1932. The popular and financial success of Cold Comfort Farm, published that year, had allowed her to give up her first career in journalism. However, like her other twenty-five novels, Westwood was completely eclipsed by this early success and remained out of print for many years. Thanks to the efforts of writer Lynne Truss, Westwood enjoyed a revival in the form of a radio adaptation and was subsequently reissued by Vintage Classics in 2011.

Westwood introduces the reader to the world of Gerard Challis, high ranking civil servant and experimental playwright, viewed through the adoring gaze of young teacher Margaret Steggles. Margaret has recently arrived in Highgate to take up a teaching post, believing that only in London can she attain the higher aesthetic plane she longs to inhabit. Already an admirer of Challis’s plays, the chance find of a lost ration book on Hampstead Heath brings her within his orbit, which is peopled by his rather unpleasant family and a retinue of domestic staff. She becomes a kind of unpaid assistant to them, a position she’s happy to occupy in exchange for the privilege of being in his presence.

‘London was beautiful that summer.’ The opening words of Westwood set the scene for a tableau of London devastated by the Blitz, where nature seems to be reclaiming the City, as weeds grow wild between the paving stones and a hawk can be seen hovering over the ruins of the Temple. We first encounter Margaret on Hampstead Heath, walking along the path below Kenwood towards Highgate, musing on the landscape before her:

There were allotments here with giant cabbages of a rich blue-green colour: the mist, and the dim blue of the sky, and the green of the grass caught up the colour again and again, almost as far as she could see, and the leaves were huge and beaded with water, for rain had fallen that afternoon …

This lyrical description, with its palette of subtly varied colours, reflects Margaret’s taste for the picturesque and, at the same, time demonstrates Gibbons’s love of her home territory. In 1936 Stella and her husband, Allan Webb, moved from Belsize Park to Oakeshott Avenue on Highgate’s gated Tudorbethan Holly Lodge Estate, built in the Garden City style. Here, she would remain for the next forty-six years of her life. The house, today, is marked with a pink plaque thanks to the Remarkable Women of Highgate project coordinated by the Highgate Literary and Scientific Society in collaboration with the Highgate Neighbourhood Forum.

19 Oakeshott Avenue became the venue for Gibbons’s weekly Saturday afternoon gatherings held for some of London’s best-known writers. She was by all accounts a charming host, who particularly welcomed young people into her circle and they, in turn, were drawn to her open, sympathetic nature. Her need to cultivate harmonious relationships with people in all areas of life was the legacy of a difficult upbringing with a harsh, philandering father and a much put-upon mother.

The Westwood of the title, the Challis’s fine Highgate house, provides a marked and ironic contrast to Gibbons’s home in Oakeshott Avenue. It is a suitable home for its owner who basks in his brilliance as a dramatist ‘admired by the cultured few’. It comprises a tall building with smaller wings on either side, with its façade punctuated by eight long windows and a front door sheltered by a porch supported on four Ionic columns. Gibbons modelled the house on South Wood, which stood on South Wood Lane until its demolition in the 1950s.

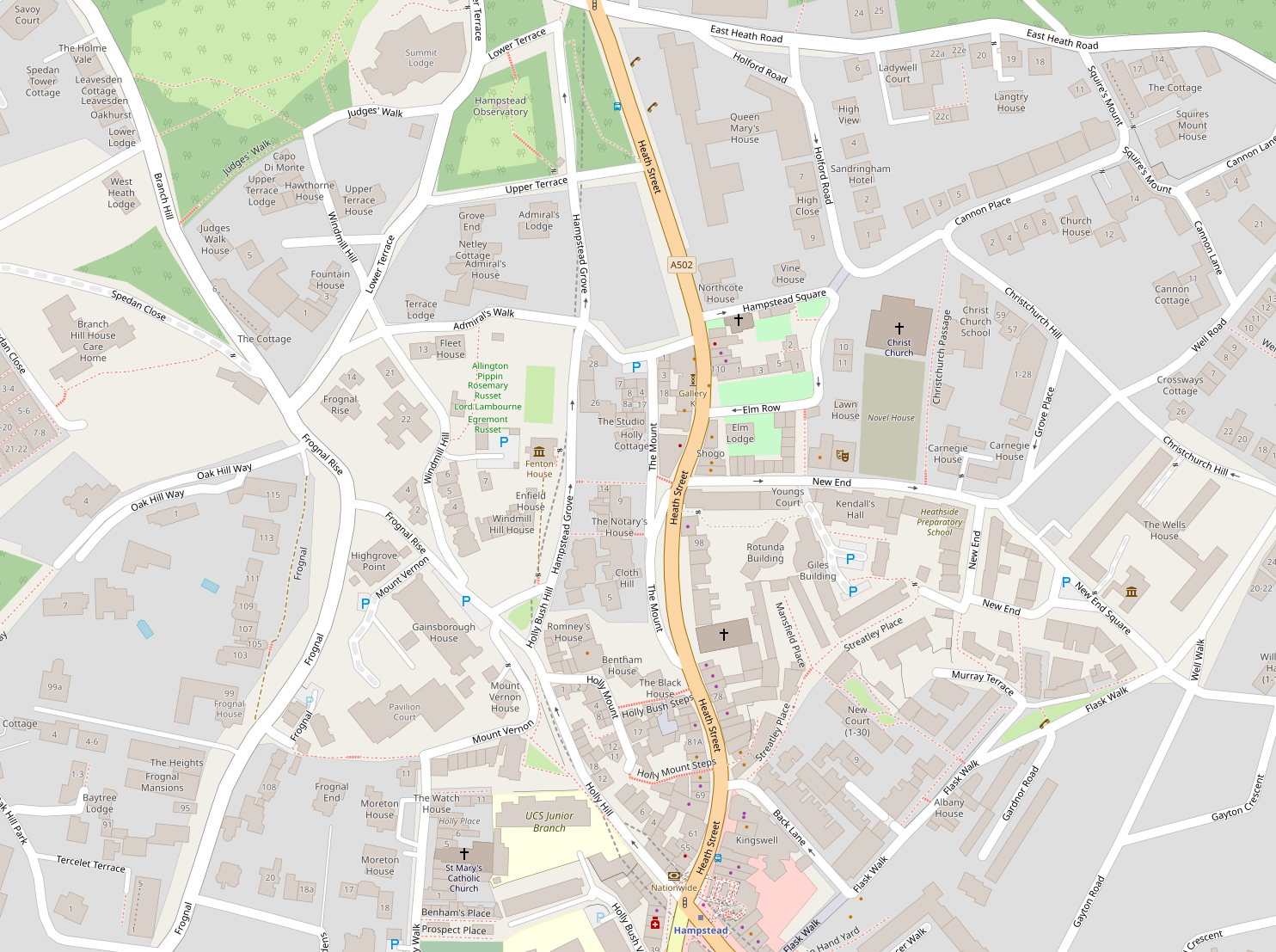

Gibbons’s descriptions of the streets and buildings of Highgate and Hampstead, with their narrow streets and pretty, historical houses, are written with such attention to detail that it is easy for any reader familiar with the villages to identify them today, even where she has renamed them. For instance, there is Margaret’s walk from the Hampstead end of Spaniards Road to Romney House, which takes her along Heath Street, down to the crossroads at the bottom, where she turns left at the clock tower, up Holly Bush Hill and on to Romney Square.

She is making her way to return the lost ration book to Challis’s daughter, Hebe Niland, at Romney House, once the home and studio of the eighteenth-century society portrait painter George Reynolds, recast here as ‘Lamb Cottage’. Gibbons creates an instantly recognisable image of the location of Lamb Cottage:

Romney Square was not a square; it was a number of old houses and their gardens, grouped irregularly about a triangle of grass, and standing (of course) on the slope of a hill. Beyond one of the houses, a charming one made of white weatherboarding, which prolonged itself into long galleries and little towers …

Gibbons’s depiction of Highgate and Hampstead functions on two levels in Westwood. First, there is the realistic portrayal of their locales. Then, there are the landscapes as she filters them through the preoccupations and propensities of her characters. As the omniscient narrator, Gibbons presented herself with the difficult feat of clearly delineating each one by means of the words and modes of expression she assigns to them. Margaret’s reflections on the landscapes she moves through demonstrate how effectively she pulls it off.

On one of her frequent walks along Simpson’s Lane to visit Westwood, Margaret sees that ‘[t]he vast city lying in the valley was blue; amethyst, sapphire, turquoise and a strange grey blue, that between the terraces making them spectral’. Gibbons’s choice of precious stones to pick out the different shades of blue and the way she evokes a kind of magical atmosphere with the words ‘strange’ and ‘spectral’ convey Margaret’s fantastical ideas about London and reveal one facet of her romantic nature, also reflected in her earlier observations about Hampstead Heath.

There is, though, another side to Margaret’s perceptions of landscape: a tendency to become rather high-flown when uneasy in her surroundings. For example, coming home from school on the bus, she looks through the window, as it passes through Canonbury, and dwells gloomily on the dangers out there on the streets, the murderers and mysterious threatening figures lurking in the dark, and

Those words of Winston Churchill, ‘a darkness made more sinister by the lights of a perverted science’ returned to her again and again as she watched the search lights sweeping and probing the dull night skies …

It’s not hard to imagine how one might feel and think, sitting on a bus during the blackout in war-time London – frightened and worried, perhaps, about ever getting home safely. By contrast, Margaret draws on Churchill’s ‘Their Finest Hour’ speech and, more specifically, his reference to the alliance between modern technology and utilitarianism, designed to subsume humanity to the exigencies of state, ‘the perverted science’.

On one of the rare occasions that Margaret ventures out from central London to the outer reaches of the Northern Line on a visit the fictional Brockdale, her reaction is similarly overwrought. Where some might see an ordinary suburban street, Margaret beholds ‘a nightmare fairy tale location like the lolly pop house in the opera of Hansel and Gretel’.

Margaret can’t come to much harm weaving dreams about London landscapes, but her delusions about Gerald Challis blind her to some very obvious faults. Here he is considering the quality of his work:

he did work hard at his plays. Sustained by a sense of their excellence and importance and of his own unusual gifts, he laboured over their plots and their characters and their dialogue (which was full of references to Saint Augustine and mathematics) …

Challis’s words expose the full extent of his pomposity and self-regard, while Gibbons’s, in brackets, hint at a far less flattering evaluation.

Challis was based, in fact, on the writer Charles Morgan. Now almost entirely forgotten, Morgan’s plays were critically acclaimed by audiences in London and Paris in the mid twentieth century. Gibbons couldn’t stand him; his inability to create believable characters, his lack of any sense of humour and intolerance of criticism. She was vocal about her opinions of Morgan and a number of other prominent members of the literary establishment, and some argue that her obvious contempt for such figures accounts for how quickly most of her books went out of print and why Cold Comfort Farm was the only one to gain classic status.

Margaret continues to revere Challis, until she comes across him one day in a bluebell glade in Kew Gardens, where he is declaring his love to her friend, Hilda. It can be no accident that Gibbons staged the final scattering of Margaret’s schwarm on the other side of London, far from all the enchantments of Highgate and Hampstead. Once the dust has settled, a while after the encounter, Margaret reflects on the experience:

In that moment the disillusionment which (she now realised) had been gradually approaching, was completed.

[…] now she saw with her own eyes that he was as other men; a disloyal husband, a weak admirer of pretty faces.

With the spell broken, Margaret’s thoughts are expressed in plain, direct words.

Stella Gibbons never moved further than a couple of miles from her birthplace, Kentish Town. As an adult she had homes in the Vale of Health on Hampstead Heath, Belsize Park, and Highgate, where she died aged 87 in 1989. In Westwood she was able to use her intimate knowledge of the area to create an authentic backdrop for a cast of characters we can easily imagine living in their north-western corner of London’s High Bohemia. In a parallel process, Highgate and Hampstead become a sort of projection screen for their aspirations and longings, a device employed to especially good effect in Gibbons’s exploration of Margaret Steggles’s transition from naïve fantasist to a mature adult, who develops the capacity to see the world as it really is and learns to bear the inevitable disillusionment it entails.

Gibbons’s nephew, Reggie Oliver, became close to her in the final years of her life. He wrote Out of the Woodshed: The Life of Stella Gibbons, published in 1998, the source of the biographical material included in this review.