Susie Thomas

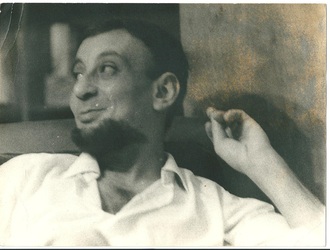

[What did Waguih Ghali look like? There can be few modern authors whose likeness is so little known. No photograph of Waguih Ghali is published in the recent editions of Beer in the Snooker Club, and the only image which comes up on a web search is not of him. So it’s quite remarkable to be able to include with this article the photograph above. It’s from Diana Athill – the only photo she has of Ghali. It was taken by a professional photographer in Paris – Diana Athill believes it dates from before she knew Ghali, probably the early 1960s. The photograph is posted here with Diana Athill’s permission, for which London Fictions is very grateful. It cannot be used elsewhere without her consent. Then … shortly after this article was first posted, two other images of Ghali, one with Diana Athill, appeared on the internet, here’s the link.]

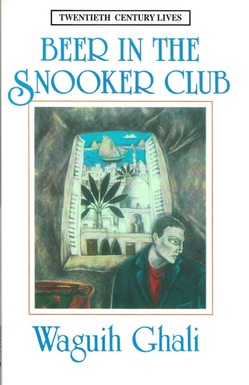

Waguih Ghali’s only published novel, Beer in the Snooker Club, is wonderfully funny as well as tragic. It is a love letter to two cities: Cairo, where he spent much of his youth in the 1940s; and London, where he committed suicide in 1969. For the central character of the novel, Ram, as for his creator, London’s literary and political culture acted as a powerful magnet and yet he also feels that ‘the mental sophistication’ of Europe has ‘killed’ his natural self. The novel moves back and forwards between Cairo and London as Ram finds himself adrift between countries and cultures, radicalised by the 1956 British invasion of his native land, but demoralised by the intolerance of Nasser’s brand of Arab nationalism.

Not much is known about Ghali’s life. I once queued at a book-signing to ask Edward Said about him: ‘Ah, Beer in the Snooker Club,’ he said immediately: ‘A wonderful novel! Sadly that’s all I know.’ Diana Athill, who was Ghali’s editor and lover, provides the main source of biographical information in her memoir, After a Funeral (1986). Ghali’s family were Coptic Christians and part of Egypt’s landowning, cosmopolitan elite. They were members of the exclusive Gezira Sporting Club, which is mocked in the novel as a place where ‘middle-aged people play croquet’: today its website boasts that it has the ‘oldest golf club in Africa’.

Athill believes that the former UN Secretary General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali was a cousin. Ghali himself was the poor relation, with the insight that so often goes with not being a fully paid up member of the club. His father died soon after he was born and his mother remarried when he was eight. His childhood was one of emotional humiliation and neglect as he was passed around the wealthy relatives. Although he remained loyal to his extended family, he became estranged from them politically, hating the way they squeezed the peasant farmers (fellaheen) for rent, which they spent on shopping sprees in Paris and Rome. Ghali grew up speaking fluent French but his Arabic was ‘deplorable’; English was his literary tongue.

‘The only important thing which happened to us was the Egyptian revolution’

Ghali viewed his life as raw material for literature and he gave Ram, the narrator of Beer in the Snooker Club, a similar upbringing to his own. In the novel Ram takes part in the student demonstrations against the British occupation of Egypt. Later, he and his friend, Font, are taken to London by an older Jewish-Egyptian woman called Edna with whom Ram is in love. When the 1956 Suez War occurs Ram is shocked: ‘In spite of all the books we had read demonstrating the slyness and cruelty of England’s foreign policy, it took the Suez war to make us believe it.’ Ram joins the Communist Party and is deported from England after hitting a policeman during a demonstration in Trafalgar Square.

He returns to Egypt hoping that Nasser will have significantly changed Egypt’s feudal society in the four years Ram has been in London. Ram and Font supported the 1952 revolution ‘wholeheartedly and naturally, without any fanaticism’ but they are bitterly disillusioned on their return to Egypt to find that injustice and corruption are still rife: the fellaheen are little better off, despite Nasser’s attempted land reforms, and Jews and communists are persecuted. The beautiful Edna has been whipped by a soldier (because she is Jewish) and her face is badly scarred. Ram and Font seem to drift, disillusioned idealists, drinking homemade “Bass” — an interesting-sounding cocktail of Egyptian Stella, vodka and whisky. As a superfluous intellectual, Font has been found a job ‘brushing the snooker tables with the Literary Supplement.’ In order to engage in meaningful political activity, Ram secretly gathers evidence of torture in Egyptian prisons for a human rights organisation at considerable personal risk. But his activism backfires: Ram has ‘the terrible feeling that some of the pictures wouldn’t be so gory if we didn’t pay for them’ and none of the newspapers dares to publish them anyway. Overcome with a sense of futility, the novel ends with a cynical Ram heading off for a night of gambling and getting drunk in Groppi’s, Cairo’s most elegant café.

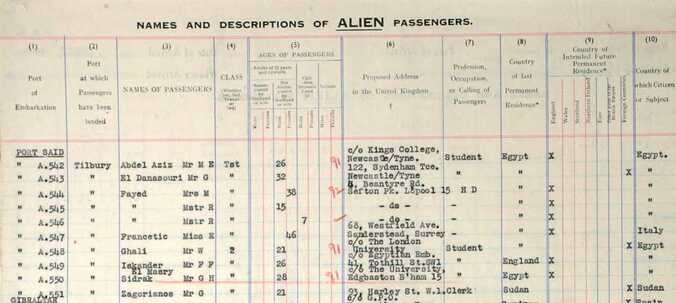

In real life, Ghali was forced to leave Egypt in 1958 under threat of arrest for being a member of the Communist Party. He was living in London when his passport expired: unable to either return to Egypt or stay in England, he was exiled to Germany where he worked in a factory and wrote Beer in the Snooker Club. Tragically, Ghali was unable to complete his second novel, based on his miserable experience as a gastarbeiter, and he died of an overdose in 1969 in Diana Athill’s flat. In every way, Ghali’s social position placed him betwixt and between: an anti-colonialist who was also an Anglophile; a communist with aristocratic tastes; an Arab nationalist who could not write in Arabic; a member of the elite who was also an outsider.

There are three Londons in Beer in the Snooker Club: the London of Ram’s dreams; the city he lives in for four years, which changes him irrevocably; and the memory of London, which haunts him on his return to Cairo.

‘“Life” was in Europe’

The London Ram dreams about as he lies on his bed in the sweltering hot afternoons is a place of literary fantasy: ‘a whole imaginary world … where pubs were confused with zinc bars and where Piccadilly led to the Champs-Elysees’ :

I wanted to live. I read and read and Edna spoke and I wanted to live. I wanted to have affairs with countesses and to fall in love with a barmaid and to be a gigolo and to be a political leader and to win at Monte Carlo and to be down-and-out in London and to be an artist and to be elegant and also to be in rags.

Having devoured all the London fiction they can get their hands on, Ram and Font set sail from Port Said to Tilbury.

‘Jesus, Font; here we are, London and everything’

Unlike the majority of writers from the colonies who came to London in the 1950s and 1960s, Ghali was not disappointed by the city of his dreams. Partly, this must have been because as an Egyptian he was not subjected to the kind of racial prejudice that Africans and West Indians routinely suffered at this time. In Sam Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners, ‘the boys’ are turned down for jobs and housing when they show their faces but no one spits at Ram or points at him in public. One potential landlady asks Ram if he is ‘coloured’. He isn’t sure himself so he goes to the library and discovers that he is officially ‘white’. For the most part he seems amused by the prejudice he encounters. Like the morning when Ram, Font and Edna are talking in Ram’s hotel room in Hyde Park Corner:

The maid suddenly came in and said: ‘Oo, ’xcuse me.’

‘Not at all, luv,’ I said. ‘Come in, we’re one short.’

She went out saying, ‘goings on’, and then said ‘wogs’ which angered Font and Edna but made me burst out laughing.

The friends make literary pilgrimages to the places they have read about: ‘We took the underground to Aldgate and walked in Commercial Road, looking for W. W. Jacobs’ people.’ Jacobs (1863-1943) was the once popular author of comic maritime tales and ghost stories. It seems a dark irony that Ram should track down the setting for ‘The Brown Man’s Servant’, about an avaricious Jewish pawn broker who is destroyed by a sinister Burmese who practices black magic. The story is a thesaurus of racist stereotypes, written by the son of a London docker, who was probably of Jewish descent.

Edna mockingly tells Ram that an Egyptian who loves W.W. Jacobs cannot possibly be refused permission to stay in England. A series of ‘nasty and humiliating’ interviews at the Aliens department is enough to ‘dissipate all our illusions’ and eventually he is deported.

But in the beginning of his stay in London, Ram is delighted simply to walk in the streets. First, he discovers the area around the Edgware Road:

A gang of teddy boys, Irish labourers and other odds and ends used to play dice on the pavement. We Egyptians are gamblers. It’s not that we want to make money or anything, we just like to gamble. Font and I won a lot of money on that pavement once, and went to a silversmith on Edgware Road and bought the two silver beer mugs we now keep behind the snooker club bar.

Today the Edgware Road, lined with shisha cafes and Lebanese restaurants, is known colloquially as Little Arabia. Although Egyptians began to settle in this area when Ghali was writing Beer in the Snooker Club, Ram is not interested in finding other Arabs. On the contrary, he is on a quest for authentic, or at least, literary Englishness.

Today the Edgware Road, lined with shisha cafes and Lebanese restaurants, is known colloquially as Little Arabia. Although Egyptians began to settle in this area when Ghali was writing Beer in the Snooker Club, Ram is not interested in finding other Arabs. On the contrary, he is on a quest for authentic, or at least, literary Englishness.

Carrying a letter of introduction from his headmaster in Cairo, Ram and Font visit the Dungates in Hampstead: ‘We walked and watched and felt the little hustle of people at Hampstead station penetrate to us.’ They feel obscurely that ‘Hampstead was more England than Knightsbridge.’ As they walk up the narrow, sloping street to the house, Ram fantasises that a butler will ‘usher’ them in and offer them Ouzo ‘or whatever we Arabs are supposed to drink.’ Although Jeeves fails to materialise, the Dungates and their adult children take Ram and Font to the pub where they discuss left wing politics and anti-colonialism before going home to eat a traditional Sunday roast.

Ram is delighted that reality conforms so closely to his fantasy, and impressed that the English can criticise their own foreign policy. But he is appalled to discover that he is developing a split self : ‘the one participating and the other watching and judging.’ Ram develops a bad case of colonial schizophrenia exacerbated by an awareness of class.

When Ram learns that one of the Dungate’s young female cousins was raped and murdered by a gang of Egyptians in Suez, he retreats to his hotel room to console himself with the fantasy of being an anti-Imperialist hero. He imagines giving a magnificent diatribe to a huge audience in a pub:

When an Englishman wants a thing, he never tells himself he wants it. He waits until there come to his mind a burning conviction that it is his moral and religious duty to conquer the people who possess the thing he wants, and then he grabs it. When he wants a new market for his adulterated goods, he sends a missionary to teach the natives the gospel of peace. The natives kill the missionary, the Englishman flies to arms in defence of Christianity, fights for it, conquers for it, and takes the market as a reward from heaven.

This is a fair critique of the rapacity which lay behind the rhetoric of the white man’s burden, but the reader is also aware that Ram needs to justify the death of the Dungate girl and to maintain the simplistic paradigm of Imperial oppressors and victimised natives.

Typically, although Ram is sarcastic about the English, he is also self-mocking:

This speech wasn’t Bernard Shaw, but my own spontaneous composition. And at the end there was a colossal silence and then a phenomenal ovation with tears in some eyes and all the women begging me to be their lover.

Ram starts to see the Dungates, and gradually all the English people he meets, as types rather than human beings. He is particularly appalled to realise that his judgment of others is based on class.

When Ram and Font and Edna visit the Kilburn flat of Mrs Ward, a conductress they meet on the bus, he notices that they do not buy her flowers although they took a bouquet for Mrs Dungate. Mrs Ward is nice, Ram thinks, but she is boring. Worse, when they go to the pub in Kilburn (where, Edna informs him, the Irish live), Mrs Ward’s son Steve starts to talk about his time as a soldier stationed in Suez. Steve spouts the typical English prejudices of the time: ‘you know what the wogs are like’ — without realising that Ram and Font will be offended. Ram encourages Steve to make a fool of himself, but Ram is the one who ends up feeling guilty because he knows that Steve is not malicious; he is just uneducated and not very bright. The scene is typical of Ghali in its humanism and in the way that class invariably trumps race in his social critique.

Ram forgives the working class Steve for his bigotry, just as he laughs at the chambermaid who calls them ‘wogs’. But when he goes to South Kensington and encounters Captain Treford’s snobbish wife, who is letting a room ‘purely out of a sense of social duty’, Ram becomes angry. Mrs Treford, who is impressed by Ram’s elegant suit and linen handkerchief, tells him that she and her husband met ‘a surprising number of very intelligent Egyptians at the Gezira Sporting Club’ while they were stationed in Cairo. Ram pretends to arrange for his chauffer to bring over his bags and asks if they have a garage for his Bentley before storming out: ‘but somehow I didn’t feel as victorious as I might have been.’

Ram learns to navigate London’s class system as he searches for a neighbourhood where he feels at home. Fearing that he is becoming a ‘phoney’, he first decides to move to a cheap room in the East End. The fantasy of “finding himself” falters when Edna asks him gently: ‘are you sure that a room in the East End is not a part of the books you have read?’ The temptation to sentimentalise poverty is crushed by a brief taste of the reality: ‘After walking in the East End for a whole day, I decided I wouldn’t like to live there after all’.

In terms of class, if not geographically, Ram finds a halfway house between South Kensington and Bethnal Green by moving to Battersea. He takes a room with a mechanic’s family and ‘strangely enough I began to live’.

When all Ram’s savings have run out, and he is unable to work or renew his visa, he finds that his only friend is Vincent, a working-class free thinker, whom he met through the Ward family. As the Dungates and his other ‘New Statesmen friends’ drop him, he finds refuge in White City with Vincent and his drunken Irish stepfather Paddy: a man so lazy that his friends say that he has ‘two large callus on the seat of his trousers’.

‘We left that day and we shall never return, although we are back here again’

On his return to Cairo, Ram is a changed man: disillusioned by England’s foreign policy, the failure of the Egyptian revolution, and crippled by class consciousness. He no longer believes in the Communist Party and gone is the breathless excitement about ‘civilization’, ‘freedom of speech’, ‘culture’. These values are contained in quotation marks, as if they are tainted.

Ram’s feelings about London on his return to Cairo are characteristically ambivalent: it is the centre of the campaign for international pacifism (Donald Soper), the anti-apartheid movement (Father Huddleston) and the home of radical writers such as Lessing, Orwell and Wells. At the same time it is the HQ of Hypocrisy, epitomised here by the reference to Churchill, who backed the White Russians against the “Bolshevik Jews” but also supported the Zionists in Palestine. It is impossible for Ram to reconcile London as the ‘centre of civilization’ with its role as the centre of the Empire.

Ram’s remembered London does not refer to a physical locality but to a state of political awareness: from the French bombing of Damascus in 1925, to the murder of the German revolutionary Rosa Luxembourg and the torture in Algerian prisons described by Henri Alleg in La Question (1958). London is the place where Ram gains an understanding of history and injustice, of class and racial politics. He laments his lost innocence:

‘Oh, blissful ignorance. Wasn’t it nice to go to the Catholic church with my mother before I ever heard of Salazar or of the blessed troops to Ethiopia?’

Since London and all that, I always seem to move towards the tragic things, as if I had no free will of my own. It is funny how people – millions and millions of people – go about watching the telly and singing and humming in spite of the fact that they lost brother or father or lover in a war; and what is stranger still, they contemplate with equanimity seeing their other brothers or lovers off to yet another war. They don’t see the tragedy of it all. Now and then one of them reads a book, or starts thinking, or something shakes him, and then he see tragedy all over the place. He finds it tragic that other people don’t see this tragedy around them. Then he joins some party or other, or marches behind barriers until his own life, seen detachedly, becomes a little tragic. I hate tragedy.

Further Reading

Athill, D (1986) After a Funeral (New York: Ticknor and Fields); re-issued by Granta (2000).

El-Enany, R. (2006) Arab Representations of the Occident: East-West Encounters in Arabic Fiction (London: Routledge, 2006).

Gindi, N. (1991) “The Gift of Our Birth: an image of Egypt in the work of Waguih Ghali”, in N. Gindi (ed.), Images of Egypt in Twentieth Century Literature (Cairo: Cairo University English Department, 1991), pp. 423-43.

Hibbard, A. (1994) “Cultural Upheaval and Fictional Form: three novelistic responses to Nasser’s Egypt”, in: T. D’haen & H. Bertens (eds), Liminal Postmodernisms: the postmodern, the (post-)colonial, and the (post-)feminist, Postmodern Studies 8 (Amsterdam, Atlanta: Rodopi), pp. 317-329.

Soueif, A. (1986) “Goat Face”, London Review of Books, 3 July, pp. 11-12.

Starr, D.A. (2006) “Drinking, gambling, and making merry: Waguih Ghali’s search for cosmopolitan agency”, in Middle Eastern Literatures, 9:3, 271-285.

Thomas, Susie. “Waguih Ghali”, The Literary Encyclopedia (first published 12 September 2008)

[http://www.litencyc.com/php/speople.php?rec=true&UID=12226]

A Ghali online archive was posted in 2013, here’s the link: http://ghali.library.cornell.edu/