Lisa Robertson

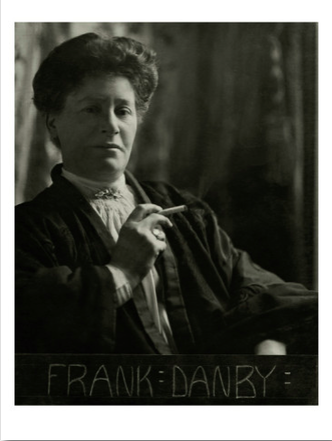

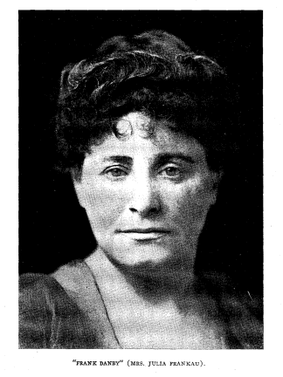

Given the impact with which Julia Frankau entered late nineteenth-century literary society, it is curious that she is mostly unknown today. After her first novel Dr Phillips: A Maida Vale Idyll (1887) caused a scandal due to its bitter criticism of the West End Jewish community in which she was raised, Frankau’s reputation as an enfant terrible was confirmed. It was not the ironic tone, the discourse of realism, or the unpleasant subject that was most shocking – but rather that the novel, printed as it was under the pseudonym Frank Danby, was revealed soon after to have been penned by a woman, and one who thought the whole event rather amusing.

Born into a wealthy Anglo-Jewish family in Dublin, Julia Davis lived the first two years of her life in Ireland before moving with her family to London after her father changed occupations from dentistry to portrait photography. Although her formal schooling was limited to an elementary education, she was later tutored by Karl Marx’s eldest daughter Laura Lafargue until the age of twelve. Frankau’s most formative education, however, seems to have been the influence of her brother James ‘Jimmy’ Davis who was a general bon vivant and notorious theatre critic who wrote under the pen name ‘Owen Hall’ (the pseudonym is said to play on his gambling bets as he was forever “owing all”). Frankau’s brother introduced her to a literary and bohemian society that included Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw, and George Moore who would become a mentor for her first two novels: Dr. Phillips and A Babe in Bohemia.

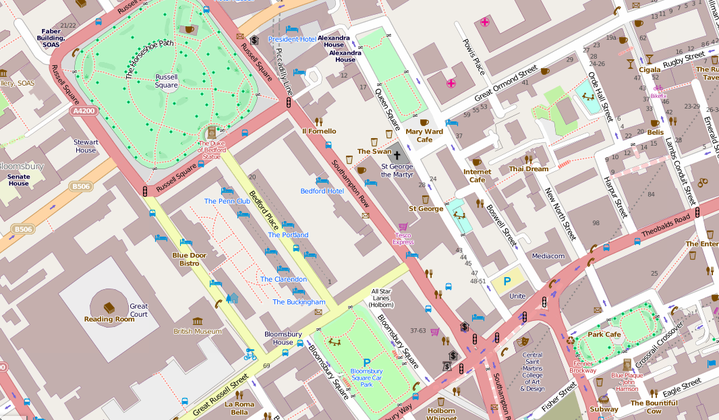

A Babe in Bohemia (1889), Frankau’s second novel, was blacklisted by the circulating libraries upon its publication. Unlike Dr Phillips, the novel had not been published by the infamous Vizetelly (who had been prosecuted the previous year for issuing Émile Zola’s work in English and sentenced to a prison term) but the press knew enough to expect ‘a further excursion into the drains and dustbins of humanity.’ This is not metaphor alone. A Babe in Bohemia satirises contemporary slum fiction and does so by taking the cause of sanitary reform and its implications of immorality out of London’s East End and placing them in a neighbourhood better known to the press and other literary types: Bloomsbury.

The eighties saw a surge in social investigative literature – both fiction and non-fiction – tackling the poverty of London’s East End, and by the end of the decade while still sensational the subject was no longer unconventional. A Babe in Bohemia satirises a number of these conventions made familiar during the period by writers like George Sims and especially Andrew Mearns, whose dramatic reportage in the pamphlet The Bitter Cry of Outcast London (1883) generated public outcry about sanitary conditions and their implied relationship to immorality. Using powerful (and often uncomfortable) Juvenalien satire, Frankau rewrites a number of conventions to make plain that the moral degradation represented in social journalism and slum novels that so fascinated the middle classes was present not only in their own back yards, but was fuelled by their own behaviour.

Sanitary Reform

The publication of Edwin Chadwick’s Report on the Sanitary Conditions of Labouring Classes of Great Britain (1842) gave momentum to the Sanitary Reform Movement, which would continue to colour public debate for remaining years of the nineteenth century. The sensationalist Report detailed the conditions of poverty across England and Wales, and in doing so laid the foundations for an urban narrative that pivots on revealing the abject condition of the poor to a middle-class readership that often resided in the same city. This discourse in both fiction and non-fiction contributed to debate that would see a number of sanitation reforms made by the century’s end. Yet as scholars like Mary Douglas have identified, the preoccupation with purification extended beyond literal pollution to concerns about moral and social pollution.

This relationship was made most explicitly by Mearns’ The Bitter Cry, which uses the discourse of sanitation reform to discuss concerns about prostitution and incest. It’s likely that Frankau thought it rich that such a pamphlet could be a best-seller, and yet novels on subjects hardly more scandalous or sensational were condemned out of hand. In A Babe in Bohemia Frankau uses the hyperbolic language of investigative journalism and sanitary reform literature to represent a terraced house in Bloomsbury as the nadir of neighbourly contagion:

It is a low house leading straight on to the street its windows are dulled with the smoke from Tottenham Court Road, and dreary with mists from Russell Square. The railings are begrimed, the stone area green and word with neglect and decay. The bell hangs loosely in its socket, and the knocker is wrenched off its bidding-place. Respectability frowns at it from over the way, whitens its steps perennially, brightens its bellhandles, and hangs up its white window-curtains”.

The interior of 200 Southampton Row interior is equally murky, but rather from owing to local industry it is the result of nightly orgies that lend the house a ‘smoke-laden atmosphere’. Just as Mearns speaks of the ‘courts reeking with poisonous and malodorous gasses arising from accumulations of sewage and refuse’, it is in this ‘hot and noxious atmosphere’, swimming in ‘general murkiness’ that Lucilla Lewisham, and her epileptic twin brother Marius (the name no doubt a jocular jab at affected aesthetes) reside.

If, as Nadia Valman suggests (in her study The Jewess in Nineteenth-Century British Literature), Dr Phillips makes use of gothic conventions, in this text they are dramatised in order to draw parallels between sensationalist non-fiction like slum literature and the theatrical narratives of gothic literature. Not only does Lucilla have an epileptic twin brother – her monstrous double – but the two have been stowed away in the house’s attic where the window is grated and the bed is surrounded by twine netting.

The narrative takes the environmental and biological determinism ubiquitous in slum fiction to reductive extremes. Like the protagonist of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts (1881), Marius has inherited syphilis from his philandering father. The representation of his epilepsy, a consequence of syphilis, allows the narrative to comment on the dehumanising characterisations of the poor in slum fiction. The text is replete with references to Marius’ animality: he is described as ‘octopus-like’, as having an ‘idiot’s animal-like desire for contact’, and writhing like ‘some dumb animal in mortal pain’ whose ‘inarticulate sphere of cries, tears, expressions of pain’ express only ‘spontaneous and animal life’. While Marius dies a dramatic death not long after he is introduced, Lucilla, the seventeen year old babe of the title, is rescued from the attic only because she becomes fresh erotic currency for the circle of morally abhorrent bohemians who populate the novel. It is the first of a series of rescue missions the young heroine has to endure, all of which place her in greater danger than they ever do save her.

The Salvation Army

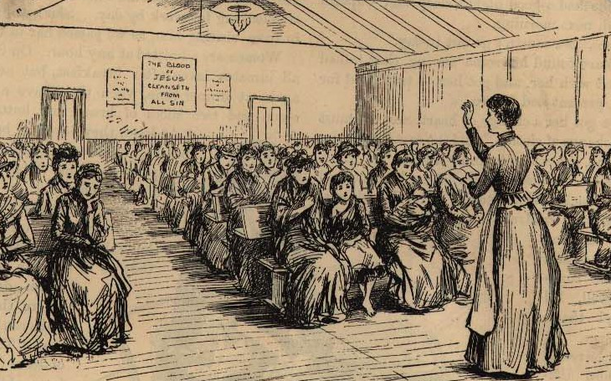

After resisting seduction by a variety of depraved bohemians, Lucilla eventually absconds after resisting the sexual advances of her father’s friend and theatre critic Mordaunt Rivers. While wandering the city’s streets at night Lucilla, attired in a white-flannel river-dress and sailor’s hat, is stopped by two ‘incongruous’ looking women in blue cloaks and poke bonnets who inquire whether she is lost. Lucilla, who understands the question to be literal, answers affirmatively and is promptly taken to the Salvation Army depot at Drury Lane in order to be ‘saved’. Just as George Bernard Shaw would later identify in Major Barbara (1907), despite its noble intentions the efforts of the Salvation Army were useless while operating in a power system oppositional to its ethos.

A Babe in Bohemia is intent on identifying the hypocrisy of the Salvation Army rescue missions. When Lucilla is asked in veiled language ‘how long [she’s] lived his horrible life’ she answers, again interpreting the question literally, ‘always’. If her imagination was free of vice and depravity before entering the walls of the depot, as the narrator points out, the lassies certainly left no stone unturned in this regard by the time the night was over. Rather than a charitable organisation the Army is characterised as a group of ‘young, hysterical, religious-mad young women…[that] instead of a religious assembly, an outsider might well imagine [to be]…some new and strangely managed institute for neurotics’.

The narrator implies that the women’s interest in the unchaste lives of others is not motivated by a desire to rescue their fallen sisters, but rather from their own repressive desires where matters of sexuality are concerned. These young women, the narrator comments ‘ranging perhaps from sixteen to thirty, drawn mostly from the ranks of middle-class life, daughters of professional men, lawyers, architects and clergymen’ are only there for want of a better vocation and instead their ‘dull provincial [lives] had lead them to religion as past-time’.

Although Lucilla does not experience the religious conversion her comrades speak of, she joins the army out of obligation to the women who have offered her food and shelter. She also does so, as the novel makes clear, because she has no other home to go to and no method of earning a living. Just as Shaw’s obverse moralist Andrew Undershaft comments that ‘[i]t is cheap work converting starving men with a Bible in one hand and a slice of bread in the other’, A Babe in Bohemia makes clear the women who are subjects of conversion are given a choice that is equally undecidable. Once Lucilla is ‘saved’ she is ‘left with and classed with…[the] refuse of the London streets’. The Rescue Home has not succeeded in its mission but has instead placed Lucilla in a more perilous position, and one which the narrative suggests – not without irony – that she can only be saved from by way of a resolution through marriage.

The Suburbs

Once Lucilla is rescued from the Salvation Army and reunited with the morally dubious character the novel has established as its hero, Mordaunt Rivers, the narrative proceeds towards an ending of domestic felicity by removing the couple from the noxious streets of London to its suburbs. The convention is one that would have been familiar to readers due to its frequent use in popular novels like Charles Dickens’ Bleak House (1852-3), itself preoccupied with the sanitary reform movement: the urban novel can only be resolved when the characters are extricated from the very environment that has impelled the narrative. However A Babe in Bohemia challenges the supposition that middle-class suburbs are any less compromising for women – especially in view of their autonomy. The novel indulges the reader’s predisposition for the marriage plot’s conventional ending:

Then she knew happiness. He took two rooms for them at Twickenham…this was the first home Lucilla had ever known. Mordaunt would sit and write, and she would watch him; she never liked to be far off him. She would sit in a chair so close beside him that she could touch his coat-sleeve now and then to assure herself she was not dreaming, but awake with him, never more to be parted.

This happy ending is somewhat compromised by the fact that Mordaunt, as it turns out, is already married. So too is Lucilla’s cloying happiness soon compromised by the isolation and utter dependence of suburban life in Twickenham:

They led a life isolated from the world, living solely for each other. Mordaunt would write in the mornings, Lucilla beside him; in the afternoons, hand in hand like two children, they would wander about the country, or, strolling down to the river, would idly float to Richmond, all the green around them framing peace and happy love. So long as she could touch him, hold his hand, know he was near, Lucilla was happy. She neither read, wrote, worked nor though; her entire being was absorbed by him. This lasted a month.

Lucilla’s experience suggests that suburbs are differently but equally threatening to women’s independence and autonomy as any urban environment; the city’s suburbs are no better – indeed probably worse – than the city’s slums. In fact, the working-class women who are patronised pitied in slum literature, like the woman who Mearns writes ‘eats her crust and drinks a little tea as she works, making in very truth, with her needle and thread, not her living only, but her shroud’ demonstrates a greater deal of self-determination than does the middle-class suburban wife interred in her own home.

Lucilla was rescued from the prison-like attic at Southampton Row only to be installed in domestic isolation where ‘[s]he had no occupation’. It is a concern Frankau would revisit in her later novel Pigs in Clover (1903), compellingly enough in a fictionalised portrait of Olive Schreiner who remains cloistered in suburbia out of devotion to a wanton lover and her resultant pregnancy.

Writers of Slum Fiction

If the novel’s happy ending is disrupted by the impossibility of marriage and the psychological suffering of suburban isolation, it is fully defeated by Lucilla’s graphic suicide which takes place on her own living room rug. This conclusion is – significantly – occasioned by a character who is a satirical portrait of the writer of slum fiction: the realist. Sinclair Furley is as unsavoury, prurient and debased as the subjects of his work. Earlier in the text when Lucilla enquires about the definition of realism she is given the following explanation:

‘A realist,’ answered Rivers gravely, ‘as De Gazet writes and Sinclair Furley exemplifies, is a gentleman who sings, writes, and paints on subjects which more decent – I beg your pardon, my definition is wandering – of which less artistic people scarcely acknowledge that they think. A realist, according to the modern acceptation of the term, is a scavenger who finds the subjects of his labours in details which modesty leaves covered and police regulations banish from public place.’

Sinclair Furley pursues Lucilla throughout the course of the narrative for the sake of enriching his experience and in order to make use of her a as the subject of his work. By attempting to seduce her he ‘scavenges’ details for a realist story by enacting its events personally, and it is an attempt that drives her to suicide when he turns up at her house in Twickenham having pursued her beyond the city.

The novel casts blame on the authors of slum literature who, while claiming to write in order to ameliorate the suffering they document, are in fact producing it. By concluding the narrative in the living room of a middle-class suburban home – the same environment where a reader might be engulfed in finishing the story – the novel implicates the audience into the tragic ending. The consumers of this literature, the novel suggests, are as much to blame as the author for the moral horrors that appear on the page in front of them.

While a nineteenth-century fallen woman might fling herself from Waterloo Bridge, or a child of the gutter might slowly close her eyes and whither away like some violated flower, A Babe in Bohemia paints no romance around the heroine’s death: ‘One effort, one – O God, help her now! And then the bright red blood gushes forth on the floor, and gushes, and gushes, from red to black’. After Lucilla’s dramatic death the narrator asks: ‘The one flower that bloomed and faded in this foul soil, died out seedless. But the soil remains. And it will bear bitter fruit. Who will purify the soil?’.

In rhetoric, the ending is much like Mearns’ pamphlet which quotes the biblical phrase ‘Whom shall we send and whom shall go for us?’ and seems a familiar call to arms for moral improvement by way of cleaning the city’s streets. The sentence, however, points less to individual morality or charity as a mechanism for improvement than it does for more meaningful change. And the novel makes clear this is impossible while appeals for change are being written by authors whose minds are more immoral, and for an audience whose practices are more unethical, than the purported horrors they claim to represent.

The “Gay, Rollicking, Careless City of Bohemia” Today

Bloomsbury’s reputation as London’s heart of literary bohemianism, for most readers, is the consequence of its association with the Bloomsbury Group. However A Babe in Bohemia offers a compelling portrait of the neighbourhood’s nineteenth-century bohemian character and allows us to trace the legacy of cultural rebellion from the late nineteenth into the twentieth century – something no doubt the Bloomsbury Group would have resisted.

Although the house at 200 Southampton Row no longer exists, the road itself remains populated with traffic and noise not all that different than the ‘midnight cabs and the midnight music, the racket and din of wine-parties and supper-parties’ of the novel. The Georgian terraced housing of neighbouring streets give us an idea of the sort of building represented in the novel, likely built on what a contemporary author, F. Mabel Robinson, refers to as ‘the ordinary London plan’ although manipulated so that the reception-rooms resembled ‘a set of Japanese boxes’.

The thespians and their coterie have been replaced by swathes of students, a group one might argue that equally takes ‘Bacchus as their god’. And until very recently (and only when local authorities began to lock its gates at night), Russell Square very much retained the spirit of erotic carousing represented in the novel.

As Todd Endelman has documented, Frankau’s descendants became her literary successors: her son Gilbert Frankau was a popular novelist and war poet, and her granddaughter Pamela Frankau was a prolific and celebrated author who wrote the novel Jezebel (1937) which was eventually scripted into a film starring another wilful woman: Bette Davis. And while Julia Frankau’s books are well-nigh impossible to find (only Dr Phillips having been reprinted in recent history), Pamela Frankau’s work appears with some frequency in Bloomsbury’s good second-hand and specialist bookstores.

Lisa Robertson is a doctoral student at the University of Warwick where she is researching the relationship between domestic architecture and literature in London in the decades around the turn of the twentieth century.

References and Further Reading

Select Primary Sources (ordered chronically)

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. Dr Phillips: A Maida Vale Idyll (London: Vizetelly, 1887).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. A Babe in Bohemia (London: Spencer Blackett, 1889).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. The Copper Crash: Founded on Fact (London: Trischler, 1889).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. Pigs in Clover (London: William Heinemann, 1903).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. Baccarat (London: William Heinemann, 1904).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. The Sphinx’s Lawyer (London: William Heinemann, 1906).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. A Coquette in Crepe (London: Chatto & Windus, 1907).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. The Heart of a Child (London: Hutchinson, 1908).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. An Incomplete Etonian (London : William Heinemann, 1908).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. Let the Roof Fall In (London : Hutchinson, 1910).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. Joseph in Jeopardy (London: Methuen, 1912).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. Concert Pitch (London: Hutchinson, 1913).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. Full Swing (London: Cassell, 1914).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. The Story Behind the Verdict (London: Cassell, 1915).

Danby, Frank [Julia Frankau]. Twilight (London: Hutchinson, 1916).

Select Secondary Sources

Aria, Eliza. My Sentimental Self (London: Chapman & Hall, 1922). An autobiography with considerable information on Frankau written by her sister, Eliza Aria, who was a society journalist.

Devine, Luke. “Reading Jewish Identity, Spiritual Alienation and Reform Judaism through the Veil of Abstract Self-Hatred, Racial Degeneration, and Anti-Semitism in Julia Frankau’s Dr Phillips: A Maida Vale Idyll”. Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary Journal 8:1 (2011). An article that focuses exclusively on Dr Phillips, but one that also makes an important case for a reconsideration of Frankau’s work.

Eccleshare, Elizabeth. “Frankau [née Davis], Julia [pseud. Frank Danby]” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press Online Edition, 2004).

Endelman, Todd M. “The Frankaus of London: A Study in Radical Assimilation, 1837 – 1967”, Jewish History 8:1-2 (1994), 117 – 154 (133). A richly detailed historical study of three generations of Frankau’s family. Later included in the book-length study listed below with minor changes.

Endelman, Todd M. Broadening Jewish History: Towards a Social History of Ordinary Jews (Oxford: Littman, 2011).

Galchinsky, Michael. “ ‘Permanently Blacked’: Julia Frankau’s Jewish Race”, Victorian Literature and Culture 27:1 (1999), 171-83. An early scholarly articles on Frankau’s writing that concentrates on its themes of racial degeneration.

Gracombe, Sarah. “Imperial Englishness in Julia Frankau’s ‘Book of the Jew'”, Prooftext 30:2 (2010), 147 -179. An excellent and adept article that concentrates on Pigs in Clover but situates this work in a comprehensive understanding of Frankau’s other fiction. Together with Nadia Valman’s work this is the best scholarship produced on Frankau’s writing to date.

Valman, Nadia. The Jewess in Nineteenth-Century British Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007). This book is path-breaking in terms of Frankau’s writing. The chapter “The Shadow of the Harem: Fin de Siècle Racial Romance” includes an expert reading of Dr Philllips that sheds light the novel’s treatment of gender, as well as cogent analyses of A Babe in Bohemia and Pigs in Clover. In this chapter Frankau’s work is helpfully situated in relation to that of Amy Levy.

Valman, Nadia. “Little Jew Boys Made Good”. ‘The Jew’ in Late Victorian and Edwardian Culture Between the East End and East Africa (London: Palgrave, 2009), pp. 45 – 64. A chapter that concentrates on Pigs in Clover, but that is helpful in terms of understanding the narrative methods by which Frankau negotiates cultural representation more broadly.

All rights to the text remain with the author.