Jane McChrystal

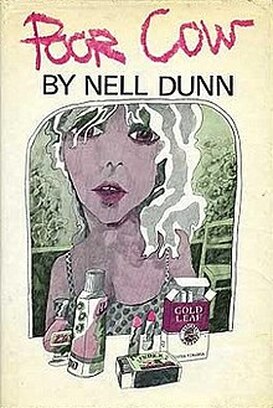

Poor Cow caused a scandal when it first appeared in 1967, and Nell Dunn’s astonishing frankness about female desire and entirely unsentimental portrayal of Joy, the poor cow of the title, still make it well worth a read today.

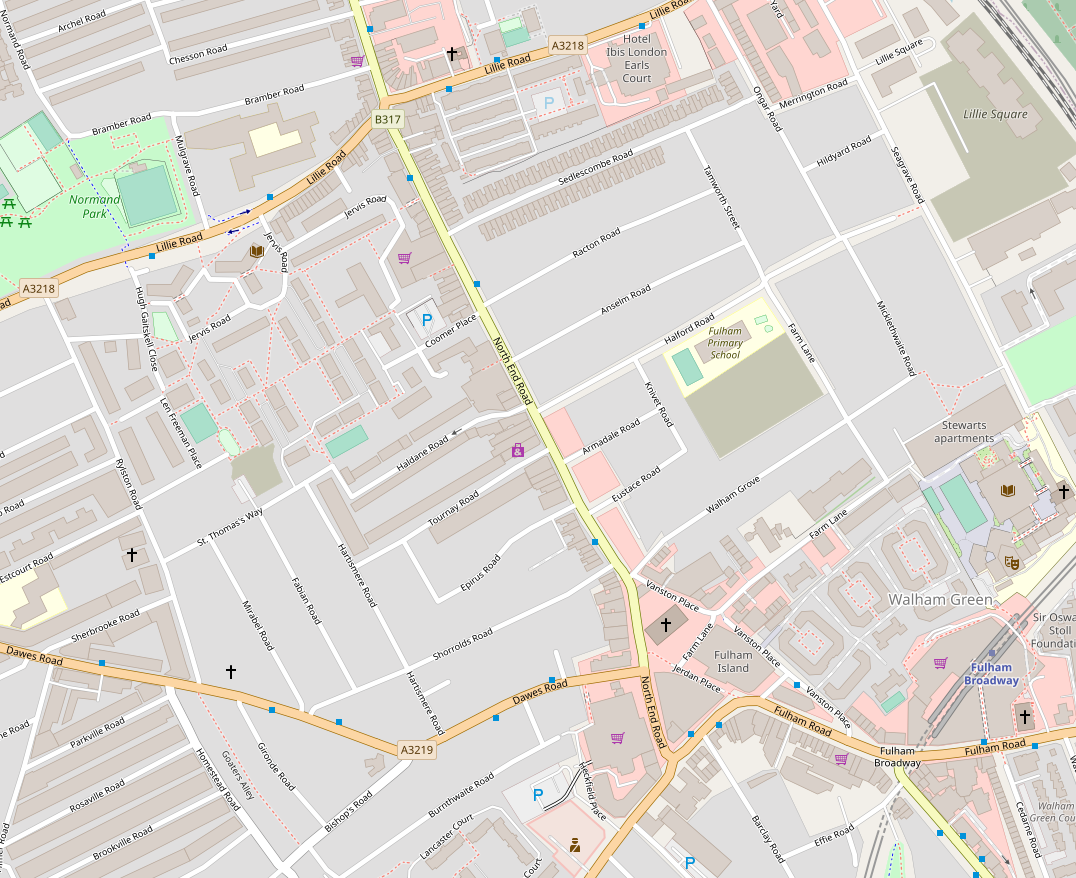

The novel is set in Fulham when its yellow brick terraces were home to a solidly working-class population of renters. Today, these houses belong to many of West London’s wealthier residents, who cleaned up their sooty facades and renovated the interiors in a wave of gentrification generated by a boom in the London property market during the 1980s.

The novel is set in Fulham when its yellow brick terraces were home to a solidly working-class population of renters. Today, these houses belong to many of West London’s wealthier residents, who cleaned up their sooty facades and renovated the interiors in a wave of gentrification generated by a boom in the London property market during the 1980s.

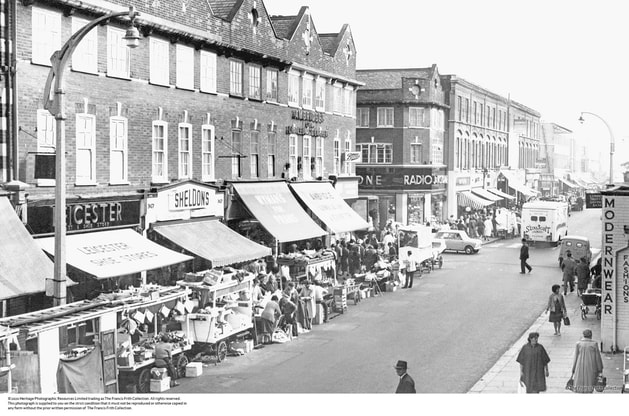

Some parts of Fulham, though, have proved resistant to change. North End Road, to name one, is lined with cab offices, cut-price hardware shops, bargain furniture stores and the market stalls, which would still be familiar to Joy who bought clothes there for her son, Jonny.

We first encounter Joy with her new-born son on her way to a café.

She walked down Fulham Broadway past a shop hung about with cheap underwear, the week-old baby clutched in her arms, his face brick red against his new white bonnet

Fulham Broadway is four minutes’ walk from Britannia Road, the boundary between Chelsea and Fulham, but the contrast between Joy’s home territory and the “Swinging London” of SW10 couldn’t be greater. Chelsea in the early sixties might conjure images of the beautiful people shopping for Quant and Courreges in boutiques on the King’s Road. Joy has to make do with cheap dolly dresses and plastic knee boots from the market.

Snatches of “What a Day for a Daydream” and “California Dreamin”, broadcast on Joy’s transistor radio, are a reminder of a cultural revolution which is passing her by. By the age of 22, she is married to a thief, Tom, and has her first child. An interlude in suburban Ruislip, funded by a particularly successful crime spree, comes to an end when Tom is picked up by the police, tried and put in prison.

Joy takes Jonny back to Fulham, where she moves into her Auntie Emm’s one room dwelling. Tom’s ex-partner in crime, Davey, turns up, they start a relationship and she moves into a council flat with him on the fictional Chancellor’s Estate. Davey is kind and warm, unlike Tom who was controlling and abusive, and life is good. Then, a burglary goes wrong and Davey is sentenced to twelve years in gaol for robbery with violence. The happiest days of Joy’s life are over.

Back at Emm’s building, Joy quickly tires of her aunt’s reminiscences about all the terrible men she has known, and takes a job as a barmaid at the White Horse pub. There, she makes friends with Beryl, another barmaid, and soon attracts a following of customers keen to get to know her better.

Her yearning for Davey is no obstacle to a string of sexual encounters with a baker, a butcher, a sailor, a hairdresser, a professor and a watchmaker, while a stint as a glamour model in a studio on the North End Road, instigated by Beryl, makes her feel sexy and alive in his absence. The days of freedom end when Tom gets out of prison and takes her and Jonny off to live in Catford. She becomes pregnant again and Tom starts to knock her around. She decides she has no choice but to stay in the marriage for Jonny’s sake and the novel finishes there.

Joy’s voice dominates the narrative and she tells us about her experiences, thoughts on men and sexual adventures in a free-flowing, ungrammatical stream. Letters sent to Davey in Brixton prison are filled with longing and bad spelling. Some might detect an air of patronage in the way Dunn, daughter of the businessman and land-owner Sir Phillip Dunn, rendered Joy’s speech and writing, but we need to remember that the upper classes didn’t regard education of their daughters as a priority in the 1950s. Dunn left her convent school aged 14 and has claimed that her own spelling is not much more accurate than Joy’s.

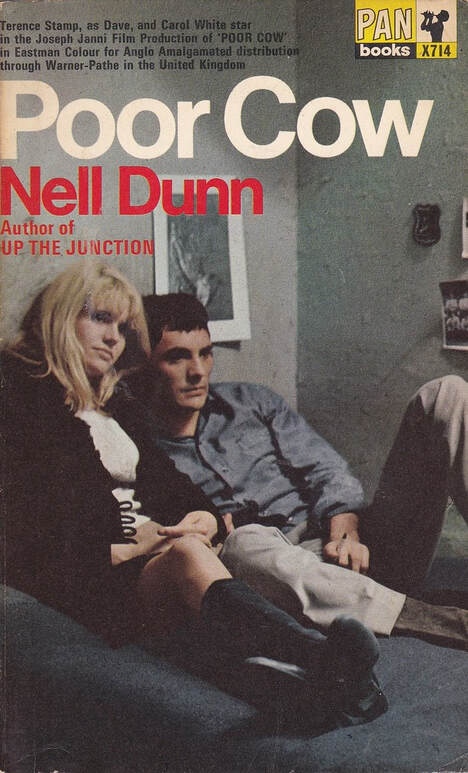

Dunn was brought up in Chelsea and married the Eton-educated script-writer Jeremy Sandford. The couple moved to Battersea where they raised three sons. Their new locale provided material for Sandford’s ground-breaking TV play “Cathy Come Home” and Dunn’s best-known work Up the Junction. Ken Loach was a frequent visitor to their home which resulted in their collaboration on the script for Loach’s film of “Poor Cow”.

Dunn was brought up in Chelsea and married the Eton-educated script-writer Jeremy Sandford. The couple moved to Battersea where they raised three sons. Their new locale provided material for Sandford’s ground-breaking TV play “Cathy Come Home” and Dunn’s best-known work Up the Junction. Ken Loach was a frequent visitor to their home which resulted in their collaboration on the script for Loach’s film of “Poor Cow”.

Dunn also took a job at a chocolate liqueur factory, where she revelled in the salty language of the workers and their openness with one another. Around the same time, she met Josie, the chief inspiration for Joy’s character, and – drawn instantly to her candour and spontaneity – began a close friendship with her.

It would be easy to dismiss Dunn as a poverty tourist harvesting material from her neighbours, but it’s clear from interviews that she found something in the people of Battersea lacking in those who shared her aristocratic background, the ability to talk directly about thoughts and feelings. She found a sense of liberation in relationships with her neighbours and the workers at the chocolate factory.

It’s undeniable that she has drawn on her experiences there to create her fiction, but she remains fast friends with Josie – they speak on the phone every day – and has documented their relationship in a recently published memoir, The Muse.

It’s undeniable that she has drawn on her experiences there to create her fiction, but she remains fast friends with Josie – they speak on the phone every day – and has documented their relationship in a recently published memoir, The Muse.

Dunn has no message to impart or axe to grind. Joy is presented to us without judgement, as she journeys onwards with little thought for the future or any real sense that she could have a say in how things turns out. She tries to seduce an examiner to get a driving licence and consults a solicitor about divorce, with the intention of taking some control of her life, but she doesn’t have what it to takes to pull it off. She just wants to enjoy whatever feels good in the moment and is simply resigned to the misfortunes that befall her.

Joy’s quite happy to live on stolen money. She enjoys the rewards of the crimes committed by Tom and Davey. She has no real desire to work, except to relieve boredom while Davey is in gaol. She’s open about the delight she takes in sex with Davey, and equally honest about seeking sexual experiences compulsively rather than in pursuit of pleasure. Joy isn’t loyal or reliable and she takes her auntie Emm’s willingness to house her and babysit Jonny for granted when she’s down on her luck. She might not even be all that nice to know.

Her visceral attachment to Jonny reveals a more sympathetic aspect of her nature, though there’s nothing saccharine about it. At first, she regarded him as a barrier between her and Tom, until the threat of losing him to illness at the age of nine weeks binds her tightly to him. She describes her intense delight in every aspect of his care, choosing his clothes, washing and dressing him and taking him into her bed in the mornings,

Even when she wasn’t with him, she could feel his weight in her arms and his mouth, after drinking, wet against her cheek – she thought of him as he raced in front of her down the road, feet splaying out like a runaway horse.

In the climax to the novel Joy searches for Jonny on the streets of Catford, after Tom has allowed him to wander off under his careless watch. In her panic she imagines his abduction, torture and pictures his cold body in a drawer in the morgue, and then, she hears his voice from an empty house, where she finds him playing with a cat and she realises:

…all that really mattered was that the child should be all right and that they should be together.

Nell Dunn has left us with a precise evocation of working-class life in London of the early 1960s, a world which has all but disappeared. She depicts a city emerging from the gloom and austerity of the 1950s. Jobs in factories and offices are plentiful and young women, like Joy, have money to spend on mass-produced fashion and having fun. Rationing and utility furniture are a fairly distant memory, so Joy can kit out her new homes in Ruislip andon the Chancellor Estate with all the household equipment and fittings she needs.

Over the six decades since Poor Cow appeared, ordinary Londoners have absorbed the language of people from the Caribbean, Africa, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. This is how language stays alive. These days, few people speak the same way as Joy, Auntie Emm and Beryl, with the exception of some of London’s more elderly inhabitants. So, we should be grateful to Dunn for making a record these voices before they disappear completely.

Dunn went to Battersea in search of a sense of freedom. She found it, together with the voices which she would record in Up the Junction and Poor Cow. There is no doubt that there was genuine empathy between her and her neighbours, attested by the enduring friendship with Josie. Unlike them, she could have left whenever she wanted. In the end, she crossed Battersea Bridge and went to Fulham where she lives to this day.

Jane McChrystal is an independent researcher and writer based on the Isle of Dogs. She writes about a wide variety of cultural and historical subjects, with a particular interest in the history of the East End of London. Her book The Splendid Mrs. McCheyne and the East London Federation of Suffragettes was published by The Choir Press in 2020.

All rights to the text remain with the author.