Dermot Kavanagh

Daniel Defoe

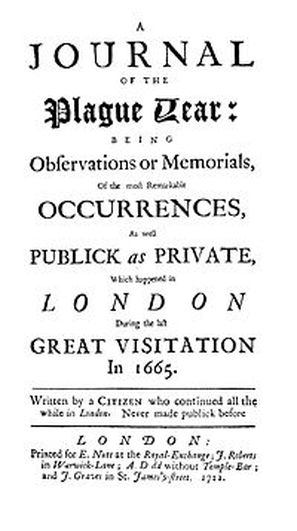

A Journal of the Plague Year is Daniel Defoe’s novel of the Great Plague of London in 1665, published fifty-seven years after the event in 1722. Defoe intended the book as a warning. At the time of publication there was alarm that plague in Marseilles could cross into England. It is a kind of practical handbook of what to do, and more importantly, what to avoid during a deadly outbreak. It is also a haunting, atmospheric portrait of London in the seventeenth century. Rich in detail, naming streets, alleys, churchyards and pubs, it chronicles the chaos of daily life during a dreadful onslaught. No definitive figure exists for the total number of deaths from the Plague but it is estimated that twenty percent of the populace died as a result. The spirit of the book calls to mind the Blitz era, with its dark East End setting and themes of human distress and fortitude.

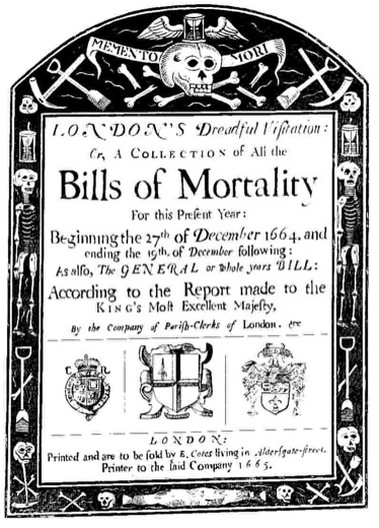

The journal style is simple and immediate and reads like an audit for the Lord Mayor’s office at times. The recurring use of weekly mortality bills to chart the spread and speed of the disease in each parish, adds to the administrative feel and gives the book an underlying authority. Defoe collected these bills, and other plague ephemera, which must account for the great amount of detail he brings to the text. But the book reads best as an historical novel that mingles fact and fiction, as Defoe was barely five years old at the time of the events. After the mortality bills, his primary sources were the many contemporaneous accounts produced in the fifty years, or so, afterwards. His genius is to construct a gripping novel filled with detail, statistics, gossip, hearsay and half-remembered stories that is totally convincing.

The journal style is simple and immediate and reads like an audit for the Lord Mayor’s office at times. The recurring use of weekly mortality bills to chart the spread and speed of the disease in each parish, adds to the administrative feel and gives the book an underlying authority. Defoe collected these bills, and other plague ephemera, which must account for the great amount of detail he brings to the text. But the book reads best as an historical novel that mingles fact and fiction, as Defoe was barely five years old at the time of the events. After the mortality bills, his primary sources were the many contemporaneous accounts produced in the fifty years, or so, afterwards. His genius is to construct a gripping novel filled with detail, statistics, gossip, hearsay and half-remembered stories that is totally convincing.

A good journalist, he resists the temptation to sensationalise events realising that the story is itself sensational enough. The author, signed only as ‘H.F.’, is the main character with few other names given. He is the ever-present narrator, right in the middle of things, gathering stories in the pubs and on the street, and we see everything through his eyes, if occasionally, somewhat voyeuristically.

London had been transformed in the decade before the Plague hit. The austerity of the Interregnum was replaced by the energy and frivolity of the Court of Charles II. People were attracted to the capital as a place of opportunity, fashion was back in favour and entertainment was no longer frowned upon. London was a liberal, dynamic destination.

the wars being over, the armies disbanded, and the royal family and the monarchy being restored…the town was computed to have in it above a hundred thousand people more than it ever held before…All the old soldiers set up trade here…All people were grown gay and luxurious, and the joy of the Restoration had brought a vast many families to London.

The net effect was more people living in crowded and insanitary conditions than ever before, alongside a thriving population of rats, whose fleas carried the plague.

The net effect was more people living in crowded and insanitary conditions than ever before, alongside a thriving population of rats, whose fleas carried the plague.

The outbreak was believed to have started in December 1664 after goods imported from Holland were carried to a house in Long Acre. Initially deaths were few and restricted to the St. Giles and Long Acre areas. By June however, there were signs it had spread to the City and after sixty-eight deaths in St. Giles, the hope it would be short-lived and parochial was shattered: ‘Now there died four within the city, one in Wood Street, one in Fenchurch Street and two in Crooked Lane’.

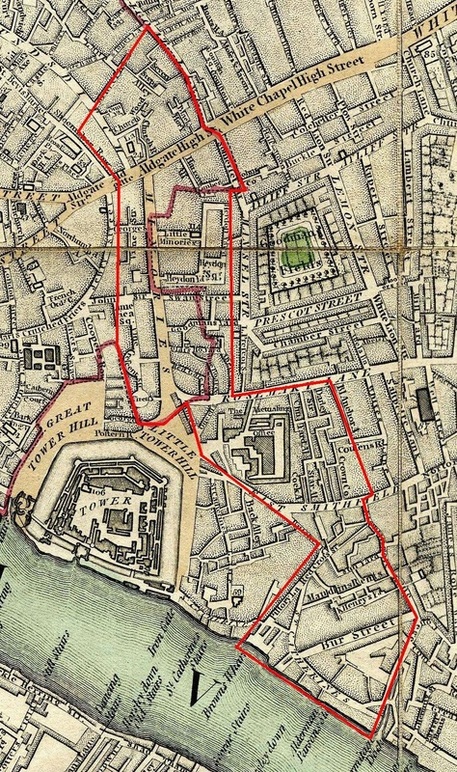

The author, a well-connected city merchant, locates his address with characteristic exactitude: ‘I lived without Aldgate, about midway between Aldgate church and Whitechapel Bars, on the left hand or north side of the street’. (Whitechapel Bars marked the eastern boundary of the City’s liberties at the junction of Aldgate High Street, Whitechapel High Street and Petticoat Lane).

The six months it took for the disease to establish itself are portrayed as a time of ignorance and denial as a kind of ‘phoney war’ mentality held sway:

people had for a long time a strong belief that the plague would not come to the city, nor into Southwark, nor into Wapping or Ratcliff at all…many removed from the suburbs…into those eastern and south sides as for safety, and, as I verily believe, carried the plague amongst them there.

Low-level fear was exploited and as unease grew, so did the number of street astrologers, wizards and quack doctors. Chancers and opportunists spotted a gap in the market and the streets filled ‘with a wicked generation of pretenders…if but a grave fellow in a velvet jacket, a band and a black cloak…was but seen in the streets the people would follow them in crowds’.

That London archetype, the quick-witted, fast talking con-man is represented by a ‘quacking sort of fellow’ who advertises himself as a self-styled expert, diagnosing plague symptoms with the slogan ‘he gives his advice to the poor for nothing’ in capital letters. After examination he recommends his exclusive ‘remedies’ to the patient for the fee of half a crown, responding to any complaints with the rejoinder ‘I give my advice for nothing, but not my physic’. Inevitably, he is nowhere to be seen when the disease manifests itself.

Following the example of the Court,which removed to Oxford in May, the wealthiest households fled to their houses in the country, as they did so their servants fearful of being left behind, if taken ill, sought out preventative cures and remedies. Defoe likens the clamour to a type of mass hysteria: ‘mad upon their running after quacks and mountebanks…it is incredible how the posts of houses and corners of streets were plastered over with doctor’s bills and papers of ignorant fellows’.

As the pace of the infection picked up during the summer months, the physical and psychological toll is graphically imagined. Defoe switches styles between a straightforward re-telling of events and first hand, eye-witness accounts. He vividly describes the suffering the symptoms caused:

those spots they called the tokens were really gangrenous spots, or mortified flesh in small knobs as broad as a little silver penny, and as hard as a piece of callous or horn..no instrument could cut them, so that many died roaring mad with the torment.

The mental effect upon the author is feverish too. He writes in a heightened, emotional state about the suffering of his neighbours. The intensity and violence of their deaths is described in the manner a Gothic horror story:

mothers murdering their own children in their lunacy, some dying of mere grief as a passion…others frightened into idiotism…

I wish I could repeat the very sound of those groans and of those exclamations that I heard from some poor dying creatures when in the height of their agonies…and that I could make them that read this hear, as I imagine I now hear them, for the sound seems still to ring in my ears.

The most controversial containment measure ordered by the Lord Mayor’s Office was the policy of shutting up houses. If illness was evident or suspected, the City had the power to sequester a property and shut it up, along with it’s inhabitants, for a period of one month, or until the plague had passed. Armed watchmen were posted at front doors so families were, in effect, put under house arrest. By this method whole households were condemned to a slow and dreadful death. Defoe spends a large part of the novel decrying the practice for its inhumanity and general ineffectiveness. He cites one example: ‘one citizen who having thus broken out of his house in Aldersgate Street, went along the road to Islington; he attempted to have gone in at the Angel Inn, and after that the White Horse, but was refused, after which he came to the Pied Bull’. Next morning he is found dead. ‘His clothes were pulled off, his jaw fallen, his eyes open in a most frightful posture, the rug of the bed being grasped hard in one of his hands’. Defoe adds pointedly: ‘whereas there died but two in Islington of the plague the week before, there died seventeen the week after’

With the disease tightening its grip and the death toll soaring, the author is forced to stay close to home. He observes what happens in his immediate locality, the triangle between Aldgate, Petticoat Lane and Houndsditch. A powerful sense of place is created in a claustrophobic, twilight world of rookeries and alleyways. The churchyard at Aldgate (now St Botolph’s without Aldgate) becomes a mass grave as a large pit is dug ‘about forty feet in length, …and about fifteen or sixteen feet broad…and about nine feet deep…lying in length parallel with the passage which goes to the west wall…out of Houndsditch, and thus east again into Whitechapel’.

Again as an eye-witness he reports what he sees one night in the churchyard: ‘I saw the links come over from the end of the Minories, and heard the bellman, and then appeared a dead cart’, a becloaked, muffled figure comes in to view, ‘oppressed with a dreadful weight of grief indeed, having his wife and several children all in the cart…no sooner was the cart turned round and the bodies shot into the pit promiscuously…but he cried out aloud,…the buriers ran to him and they led him away to the Pie Tavern, over against the end of Houndsditch, where it seems the man was known’.

Coleman Street, which runs off Moorgate is singled out as remarkable for the great number of alleys and thoroughfares it contains,most so tight that the dead cart cannot gain entry to them. The under-sexton or gravedigger, of St Stephen’s Church is forced to improvise by using a hand-barrow, perhaps taken from one of the nearby markets, to collect corpses through, ‘Whites Alley, Cross Key Court, Swan Alley, Bell Alley, White Horse Alley, and many more’.

In late August, during the worst phase of the outbreak, the author shuts himself indoors for a fortnight. The area known locally as the Butchers Row is particularly badly hit and as he watches:

out of my own windows…from Harrow Alley, a place full of poor people, most of them belonging to the butchers, or to employment depending on the butchery…Almost all the dead part of the night the dead-cart stood at the end of that alley…and as the churchyard was but a little way off, if it went away full it would soon be back again.

He finally ventures out again on a hunch that the river might offer better protection. He walks out along by Bow to Blackwall Stairs where he meets a solitary lighter-man. In one of the only direct conversations in the novel the author asks him how things are: “Alas sir!…all dead or sick. Here are very few families in this part, or that village (pointing at Poplar), where half of them are not dead already, and the rest sick”. When asked how he can make a living at such a time he replies,

“Do you see these five ships lie at anchor (pointing down the river a good way below the town), and do you see eight or ten ships lie at chain there? (pointing above the town)…All these ships have families on board… I tend on them and fetch things for them…I row up to Greenwich and buy fresh meat there, and sometimes I row down the river to Woolwich and buy there; then I go to single farm-houses on the Kentish side, where I am known…and buy fowls, eggs and butter, and bring them to the ships”.

He accompanies the waterman on his errand to Greenwich: ‘I walked up to the top of the hill. But it was a surprising sight to see the number of ships which lay in rows, two and two, …not only quite to the town, between the houses which we call Radcliff and Redriff, which they name the Pool, but even down the whole river, as far as the head of Long Reach…I could not but applaud the contrivance…for ten thousand people…were certainly sheltered here from the violence of the contagion’.

The total number of deaths according to the bills was 68,590, but Defoe disputes this and estimates that over 100,000 were killed by the plague. At its peak in late August, early September he believes 8,000 people died per week, and relates the anecdotal claim that 3,000 died in one night alone.

Defoe captures the pragmatic fatalism of Londoners but never condemns their behaviour, even in the most abject of circumstances. Unlike say Dickens, he never sentimentalises or moralises about the East End poor who bore the brunt of the ordeal. Instead he seems to admire their fortitude remarking upon a ‘brutal courage.

It is this empathy for his characters and a humane, non–judgmental tone that makes the novel so engaging. A blighted city emerges from the pages, spectral and depleted, but resilient too.

Dermot Kavanagh is the assistant picture editor at the Sunday Times.

‘Merry Islington’

The Pied Bull has the distinction of being the first house in England where tobacco was smoked. Before it became a tavern it was the home of Sir Walter Raleigh (1554-1618) who introduced tobacco to fashionable Elizabethan London.

Later, in the nineteenth century, the Inn served as a Coroner’s Court for the county of Middlesex. The Times newspaper reported in November 1827 of ‘an inquisition taken at the Pied Bull, Islington..of a remarkably fine woman, about 18 years of age, who was found drowned in the New River’. In 1849 a more sinister session was convened to investigate the death of ‘Willian Henry Crook, who was found with his throat cut in the fields near the Model Prison, Pentonville’.

Two of the pubs mentioned in the above text were within a short walk of each other. Both the Angel Inn and the Pied Bull were in the part of London that came to be known as “Merry Islington”. The Angel, Islington had gained a reputation for entertainment with it’s many pubs, theatres, open spaces and spas, albeit with a rough or violent edge. To this day it is packed with carousers looking for a lively night out.

There had been a coaching inn at the junction of Islington High Street and what is now Pentonville Road, since 1603.The Angel Inn was built in 1639 and gives the area it’s name, a reference the original pub sign, which depicted the angel Gabriel appearing to Mary at the Annunciation.

The building was replaced in 1819 and again in 1899, and remained a pub until 1921, when it became a Lyons Corner House. It was alternatively known as the Angel Café Restaurant. After the war the gradual decline in popularity of Lyons teahouses led to it’s closure in 1960.Today it’s a branch of the Cooperative Bank – next door, at 1 Islington High Street, stands a Wetherspoon’s pub named ‘The Angel’.

In the twentieth century, from the 1960s to the early 1990s, the pub was an important live music venue. A diary entry posted on the website of the band Madness dated 1979 reads: ‘July 31st: The Pied Bull Islington … altercation in crowd … Chas get kicked in the jollies by skin with steel dm’s on who straight away apologises … Made 190 pounds. Most so far!’ For a short time in the early 1990’s the pub was renamed the Powerhaus, continuing as a music venue, before converting to a wine bar and then into its current incarnation as a branch of the Halifax building society.

The address is 1 Liverpool Road. – D.K.

References and Further Reading

Thomas Vincent, God’s Terrible Voice in the City, 1661

Dr. Nathaniel Hodges, Loimologia, 1720

W.G. Bell, The Great Plague in London in 1665, 1951

Links

https://www.londonlives.org/static/StBotolphAldgate.jsp

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Defoe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Plague_of_London

All rights to the text remain with the author.