Dermot Kavanagh

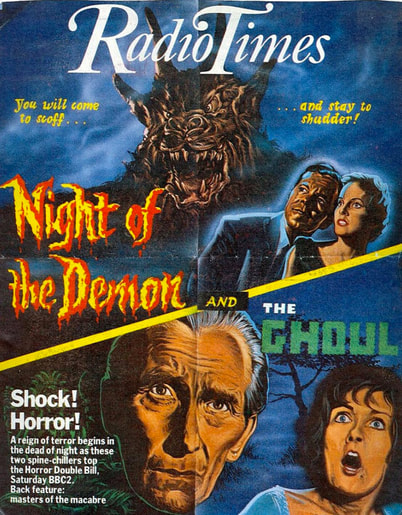

When I was twelve years old in the mid-1970s the highlight of my week-end was to stay up late with my Dad watching the Horror double-bills that were shown by BBC 2 on Saturday night. The format usually consisted of a classic Hollywood chiller from the 1930s, paired with a more modern, often British made film.

The British films were my favourite. I found them paradoxically glamorous and mundane and began to seek out anything that looked promisingly dark on television. Luckily for me ITV had a penchant for this sort of thing too, and throughout the 1970s showed a number of highly stylised domestic series, with great opening titles, such as ‘Thriller!’, ‘Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense’ and ‘Tales of the Unexpected’ which was introduced each week by the writer Roald Dahl. I can never think of the latter without being reminded of the comedian Peter Cook who memorably renamed it ‘E. L. Wisty’s Tales of the Much as We Expected’.

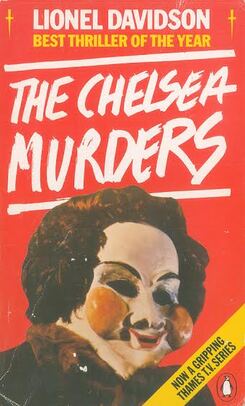

A late addition to this ITV genre was ‘Armchair Thriller’ and it was as part of this series, and ignoring the title by lying on a settee, that I first came across ‘The Chelsea Murders’. I can remember nothing about the plot, who was in it or whether it was any good, but I have never forgotten one scene.

A late addition to this ITV genre was ‘Armchair Thriller’ and it was as part of this series, and ignoring the title by lying on a settee, that I first came across ‘The Chelsea Murders’. I can remember nothing about the plot, who was in it or whether it was any good, but I have never forgotten one scene.

Shot from a video camera hidden behind a two-way mirror, the viewer is shown a room where a murder has taken place. The killer grotesquely dressed in surgical gown, rubber boots, carnival clown mask and tall curly wig is seen casually tidying up after his crime; there is no sound. Eventually satisfied, he moves to leave, but not before turning to make a slow, theatrical bow to the camera (and thus to me). I had never before felt so included and yet so threatened by the television. The simplicity of the gesture got completely under my skin.

I was unaware that ‘The Chelsea Murders’ was based on a novel by Lionel Davidson, it won the Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger Award in 1978, until many years later when I saw that familiar clown-masked figure, now dressed in an Oscar Wilde fur-collared coat, staring out at me from the front of a striking paperback. Of course I had to buy it as it is a terrific cover design; lurid, funny and a bit deranged, you can definitely judge this book by its cover. It even credits the mask’s designer, Jenny Tate, which may be a first.

The story turns on a grisly series of murders carried out by a killer with a theatrical bent who delights in taunting the police with literary quotations from dead writers, all residents of Chelsea and recipients of English Heritage blue plaques. These cryptically forecast his future victims’ identities and manner of death. The tone is blackly comic and very entertaining. Part of the fun is knowing early on in the proceedings that the killer must be one of three main characters, a louche trio of former Chelsea art students who are making a spoof Horror film together.

The story turns on a grisly series of murders carried out by a killer with a theatrical bent who delights in taunting the police with literary quotations from dead writers, all residents of Chelsea and recipients of English Heritage blue plaques. These cryptically forecast his future victims’ identities and manner of death. The tone is blackly comic and very entertaining. Part of the fun is knowing early on in the proceedings that the killer must be one of three main characters, a louche trio of former Chelsea art students who are making a spoof Horror film together.

The opening murder is related with a matter-of-fact and sadistic eye for detail worthy of late period Alfred Hitchcock. A Dutch art student is calmly despatched in her halls of residence:

Grooters remained where she was for a while, and then her murderer took off the bag. The rubber bands and pad went back in it, and everything was returned to the patch pocket, from which a small cleaver was removed. With this cleaver, the murderer proceeded to cut off Grooters head. The cleaver, of bluish steel and French made, had a small serrated portion. This dealt readily with the tough bits at the back of the neck, and the rest presented no problem. A small tug and a slice released the head, and the murderer took it and put it face-down in the hand-basin, and went and stood under the shower. This was about mid-way through the Chelsea murders.

The book is set on and around the King’s Road, which by 1978 was long past its ‘swinging London’ heyday, but still trading on its former glory as London’s trendiest street. The post hippie vibe of the area is represented by the ubiquitous jeans boutique. Bad denim, particularly in men’s fashion, was an abiding horror of the period and the King’s Road had more than its fair share of establishments selling whole outfits of the stuff to tourists intent on getting the right look. Davidson amusingly sends up the denim fetish in the character of Denny, the Chinese owner of a jeans boutique called Blue Stuff. He fussily sizes each pair of jeans with a tape measure, if the flare of the leg is under thirty inches it is rejected and sent back to the supplier, with the declaration that it may be all right for Oxford Street but not for the King’s Road. It is in Blue Stuff that two of the main characters are first introduced, Artie calls on his friend and fellow film-maker Steve who works in the shop:

The lights had come on everywhere. Going fast, not tiring, he passed rows of lighted boutiques, antique shops, restaurants, glistening in the rain. He turned in to Blue Stuff. His spirits hit bottom in Blue Stuff .The place was packed with customers, come in out of the rain, damp and reeking. Mr Blue Stuff was there himself. The Chinaman had hardly any nose and no expression at all. He was telling a young fat girl how good she looked in a cowgirl jacket. All over the shop goons were fingering denim, shuffling though hangers, looking at themselves in it in mirrors. He saw Steve fitting an elderly one in a whole stiff suit of it. The scarecrow was holding his arms up at about forty-five degrees, a whimsical smile on his face, and Steve was tugging him like a little pale gnome.

A further character on the fringe of the ex-art school crowd is local newspaper reporter Margaret Mooney, recognisable by her jeans and bicycle, she sees the murders as a career opportunity. Davidson, a former news agency man depicts the newspaper environment with fondness and wry humour. The local paper, the Chelsea Gazette, has been forced down in the world, no longer on the King’s Road, it is shunted to a far-away, back-street siding as the developers move in, pushing up rents, heralding the rise of the upwardly-mobile estate agent, who, within a few short years, would become a defining figure for this part of London.

She hated the shitty place. A regular little artisan’s cottage. They’d been kicked out of the King’s Road, together with the Chelsea News, after seventy years. The leases had fallen in. Boutiques had taken over at twelve times the rent. The same thing was happening all over Chelsea. Now they were chronicling events (to give the activity a name) from Fulham. All management had done was tart up the ground floor with plate glass and carpets and a rubber plant and put a sign over the top, Chelsea Gazette. It looked like a poofish dry-cleaner’s or a travel agency. The editorial, above, remained in its pristine squalor.

The King’s Road of the 1970s is an ideal microcosm in which to set a crime novel. A self-contained neighbourhood with a dodgy glamour and bohemian pretensions, where money and deprivation collide, from swish Belgravia apartments to shabby boarding houses hard by Lots Road power station. Book-ended by the grandeur of Sloane Square to the east, and the aptly named World’s End to the west, both areas are populated with eccentric characters who lend the book a lightness and colour that contrasts well with the gruesome nature of the killings. Suspects are tailed around its tributaries by plain clothes coppers on foot, hopping on and off buses, hailing taxis and making contact by public pay-phone. A pre-Downing Street Margaret Thatcher even gets a mention after an American called Schuster is found wrapped around a lamp-post, at the wealthy end of the road, much to the annoyance of the investigating detective Inspector Warton:

Bywater Street was a cul-de-sac lined bumper to bumper with the cars of the residents. It could only be entered from the King’s Road…Warton knew the people he had in the district – troublemakers of all kinds, judges, bankers, politicians. Mrs Margaret Thatcher, the leader of the Conservative Party, had her well-publicized abode in Flood Street, just a few yards from Schuster’s lamp-post.

Later, Mooney suspects the killer is using a room locally for storage, after scanning the classified ads in the Gazette she heads west towards the World’s End on her bicycle and enters a raw and down-at-heel bedsit land:

Mulhouse Street, when found, was such a clapped-out disaster area, she almost gave it away. But then she had another think. Disaster areas might be exactly what this customer wanted. All the right qualities on offer: anonymity, incuriosity, tolerance of all peccadilloes short of downright lunacy. She tooled slowly along it, looking for number 56. Number 56 was falling down. Four barely decipherable names adjoined bell-pushes on the rotting door frame. From her list she saw that the landlady’s was Cummings, and after much peering pressed the one most nearly approximating to it. A few minutes, and another ring later, the door opened, and a most terrible slut, dead drunk, hung on to it, in her dressing gown.

“What you want?” she said.

“You were advertising a room”, Mooney said, reeling back at the smell “in the Gazette, a couple of weeks ago. I wondered if it was still available.”

“No. Went.” the slut said, closing the door.

“Hang on. A friend of mine didn’t take it, did he?”

“What name?”

“Biffy”.

“Eh?” Same routine. Same result. The one who’d taken this one was an elderly widower from Lots Road power station; and God help him, Mooney thought. The day hadn’t begun well. And she had an idea it wasn’t the kind that just naturally got better as it went on.

For all Davidson’s naming of minor roads, bus routes and scenes set in well-known pubs of the day, such as the Chelsea Potter and the Markham Arms, there is an oddly dated feel to the books main characters. There is no mention whatsoever of the Punk scene which from 1975 coalesced around 430 King’s Road, the World’s End address of Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s clothing shop which, in different guises, survived until 1980. Admittedly by 1978 the scene had fragmented, but it was still highly visible on the King’s Road, with mohican-topped, bondage-trouser wearing punk rockers posing for photographs for years to come. Contemporary Chelsea art students would surely have been influenced by it, if only in terms of style, but the three main characters feel more like fans of Jimi Hendrix than fans of the Sex Pistols.

I wonder if Davidson spent that much time in Chelsea. With his news agency background he must have possessed a detailed knowledge of London, but he had emigrated to Israel with his family in 1966. His novel The Rose of Tibet, an adventure story published in 1962,won the approval of Graham Greene, but was written entirely from secondary sources and without him setting foot in the country.

I suspect this may be the case with The Chelsea Murders too. There is a strong sense of place, but sometimes it feels too generic, or even passe. One exception though is the best and most convincing descriptive passage in the book. Prime suspect Artie is followed by a detective named Mason into a gay club where he has gone to try and persuade the owner to let him use it for a scene in his film. The King’s Road is an important address in London’s gay history. Two pioneering clubs were located there, The Gigolo at number 328, which the writer Hunter Davies described in the late 1960s as ‘a frotter’s delight, lots of Spanish waiters and terrified Americans.’ Similarly film-maker Derek Jarman in his memoir Dancing Ledge wrote of the area in the 1970s ‘The King’s Road pioneered gay lib…bisexuality was huge’. The Gateways Club, perhaps London’s first lesbian club opened here too in the 1930s, at 239 King’s Road, and gained popularity during World War II after a huge number of women moved to London for work. In the novel a club called ‘Shaft’ is located adjacent to Cremone Wharf near to Lots Road:

The interior of Shaft was sultry red from the paper moon lanterns, but the dance floor was a swirling mass of stripes from the psychedelic slides in the reflectors. The place smelt like a barber’s and was very hot: also fairly exploding now to the thud of hard rock. Five or six hundred people were in the huge murky barn of place, a hundred or so on the dance floor, others chatting around or lounging on banquettes. A line of young male prostitutes fringed the dance floor, braceleted hands clicking, slim hips jiggling. There was a sprinkling of lesbians about. One, very dramatic in sombrero and high boots, was threading her way through the crowds, casting long looks. Another stood immediately in front of Mason, handsome in black velvet cloak and pearls; except that when she turned Mason saw it was a man, quite beautiful with green eye-liner and silvery evening purse. Mason gave him a smile, and received in return a haughty toss of the head and, presently, a backward puff of smoke from a long cigarette holder. But he had to move again. Artie was moving; up the couple of broad steps that led to the lounge and dining area.

Tables were spread here, and banquettes grouped as pews for greater intimacy. A little necking seemed to be going on, but not much, the prevailing atmosphere almost of marital propriety; partners’ hair being soothed, collars adjusted. A grave young couple, both mandarin-moustached, quietly sat and held hands as they drank in one pew. In another a raffish threesome sprawled; one of them, high safari boot cocked on a table, for all the world like a dissolute young buck just in from hunting.

In another respect the book is very much of its time. Written in the days before the concept of political correctness, some of the racial stereotyping is laughable. It can seem as if Alf Garnett has edited certain sections, especially in the portrayal of Denny the tight-fisted boutique owner, a Benny Hill Chinaman who pronounces the letter ‘R’ as an ‘L’, for (not very) comic effect, and Abo a poorly drawn, wealthy bisexual Arab. Both these unlikeable characters meet a grisly end.

With the bodies piling up and police floundering the killer is eventually caught in the act just in the nick of time. When his identity is finally revealed the motive for such a complicated and psychotic series of murders does not really convince and disappointingly feels like a mere plot device rather than anything more credible. Despite this flaw The Chelsea Murders is an enjoyable whodunnit. The ingenious plot, essentially a prolonged puzzle set over 237 pages, is written with a lightness and familiarity that is instantly engaging. It captures a Chelsea on the cusp of great change, a pre-Thatcherite neighbourhood yet to be homogenised and yuppiefied. A maverick and seedy area with the vibrant King’s Road at its heart, before it turned in to just another London thoroughfare.

Dermot Kavanagh is the assistant picture editor of the Sunday Times newspaper. He is currently researching the life of Laurie Cunningham, the first black footballer to represent England and a true maverick Londoner.

References and Further Reading

Lionel Davidson died in October 2009 aged 87 – his obituary was published in the Daily Telegraph and in the Guardian.

There is a website devoted to Lionel Davidson moderated by his son Philip: http://lioneldavidson.com/ – and there’s also a Wikipedia entry.

If you go to YouTube and search for ‘The Chelsea Murders’ you will find the Armchair Thriller version in six parts.

All rights to the text remain with the author.