Séamas Duffy

Strange, isn’t it, how much of London still lies south of the river’

– Norman Collins –

The above quotation ends ‘… just as it did in Shakespeare’s day and in Chaucer’s day’. Perhaps it isn’t strange after all; this article came to be written in the month that the remains of Roman baths were discovered at Borough Market, so perhaps the author could have added, ‘and in Caesar’s day before that’.

Norman Collins is probably better known for his pioneering role in independent television than as a fiction writer, therefore one supposes it less likely that he would appear at the top of anyone’s list of London’s misremembered authors (‘re-forgotten’ according to Iain Sinclair) than, say, Alexander Baron or Patrick Hamilton with whom he was largely contemporaneous. However, in addition to London Belongs To Me, Collins produced a fair number of other works of fiction, some of which are still in print. London Belongs To Me tells the story of the lives of the residents of Mrs Vizzard’s lodging house set amidst what Conan Doyle described as the ‘howling desert of south London’, from the period following Munich through to the height of the Blitz in Christmas 1940.

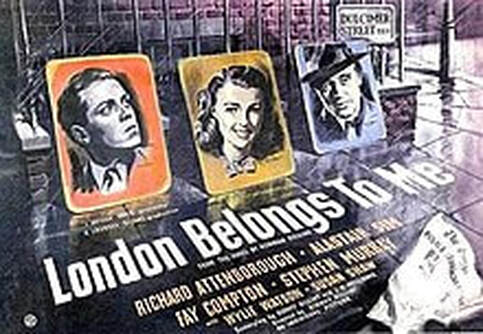

In some ways to London Belongs To Me is a difficult novel to place. It’s not highbrow literature and doesn’t even pretend to be middlebrow; and whilst Ed Glinert describes it in a recent introduction as ‘London’s great vernacular novel, a generation before Sillitoe’, one can scarcely agree with him that ‘it would not be disrespectful to call (Collins) a … pulp novelist’; it’s most definitely not a ‘war novel’ – the war, insofar as it impinges on the lives of the characters, happens largely off stage, although some of the casualties spill onto the page. Collins’s versatile palate paints a variety of moods: mild irony, savage satire and knockabout humour; pathos, misfortune, tragedy and domestic melodrama; but it fits neither into the Ealing comedy category nor could it be called a kitchen sink drama (the 1948 film of the same name is a different matter).

In some ways to London Belongs To Me is a difficult novel to place. It’s not highbrow literature and doesn’t even pretend to be middlebrow; and whilst Ed Glinert describes it in a recent introduction as ‘London’s great vernacular novel, a generation before Sillitoe’, one can scarcely agree with him that ‘it would not be disrespectful to call (Collins) a … pulp novelist’; it’s most definitely not a ‘war novel’ – the war, insofar as it impinges on the lives of the characters, happens largely off stage, although some of the casualties spill onto the page. Collins’s versatile palate paints a variety of moods: mild irony, savage satire and knockabout humour; pathos, misfortune, tragedy and domestic melodrama; but it fits neither into the Ealing comedy category nor could it be called a kitchen sink drama (the 1948 film of the same name is a different matter).

The novel rarely dwells on the bleakness or hopelessness of any situation – whether the personal tragedies of the characters, or the ravages of the Luftwaffe – for even as the bombs start falling and people either join up or get called up, life goes on with the attention focussed on the everyday, but never ever dull, life of the inhabitants of 10 Dulcimer Street Kennington: the weddings (and the almost-weddings), the conmen and petty criminals, the boxing matches, the séances, the night club raids, with the odd Nazi spy and a spot of manslaughter into the bargain.

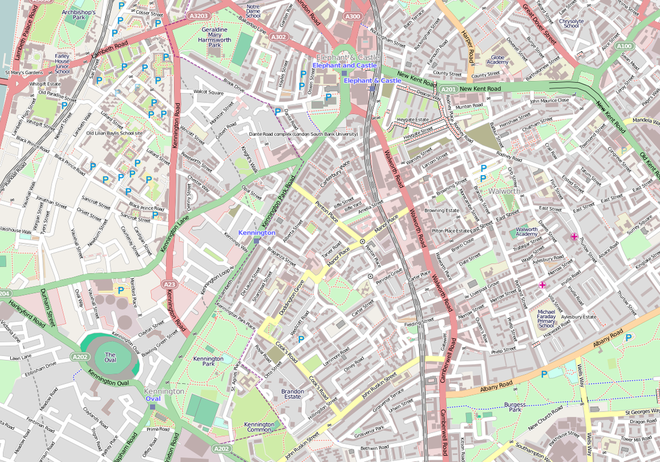

Spatially the novel is enclosed largely by the boundaries of SE5 – ‘Number 10 … in cross section, opened like a doll’s house, you’d have seen how narrowly separated the family existences (are)’ – almost all of the action takes place in an area delimited by a broad ellipse drawn between the Underground stations of Chalk Farm and The Oval with occasional forays into the City (to work as typists or clerks), to Wimbledon Common (for a spot of unpremeditated murder), or to Brighton and its satellites (holidays, and an escape from the war). Dulcimer Street remains as the fulcrum of the social and the spatial throughout – but, where, then is Dulcimer Street?

You will not find it on a map, but there would be no prizes for working out that Collins intended it to be located in the quadrant of streets bounded by Kennington Park Road, Camberwell New Road, and Walworth Road, an area which, despite its refined obscurity, holds a unique literary pedigree for it was right across the road (in the ‘Holland Grove beat’) that Conan Doyle set the scene of Sherlock Holmes’s first appearance (the murder of Enoch J Drebber in A Study In Scarlet). From the available clues it is clear that both Grosvenor Terrace and John Ruskin Street might fit the bill. Certainly only the former has the discernible curve which the novel describes, but walk down the latter from the railway bridge towards the park and even now it is possible to detect a contrast between the commercial and residential ends of the fictionalised street; a contrast that, seventy years ago, would have engendered the narcissism of infinitesimal social distinction that he wanted to satirise.

On reading reviews of London Belongs To Me, one finds that the most common descriptor is ‘Dickensian’, and in this novel Collins certainly demonstrates the ability to typify many of his characters in an onomatopaeic name coupled occasionally with a single defining characteristic – like the obese, junk-guzzling Mr Puddy (pudding, pudgy) complete with an inability to pronounce the nasal consonants; Mrs Vizzard (buzzard, lizard) a dessicated widow, picking a living from her lodgers’ rents and characterised by ‘a pale waxiness, her hair … in a hard circular knot riveted to the nape of her neck’. Upright and unsagging, formal and frigid, austerely dressed all in black with the lace cuffs which went out with Edward the Seventh, ‘she was the only person in London still wearing (them)’.

The temporarily retired and permanently bemused Mr Josser (joss stick, old josser) ‘with a wisp of white hair … like egret’s feathers’ muddles though each successive domestic disaster, haunted by his wife’s anxieties one moment and demented by his brother-in-law’s fabulous eccentricities the next; the homicidal lackwit Percy Boon (boor, loon), prey to trashy violent American culture, particularly gangster films; there is the fifth-rate spiritualist medium, slippery Henry Squales (squalid, eels) down at heel and faking his way hilariously though the séances; and the ageing, former ‘actress’ Connie Coke (conniving, croak), derelict and desperate, health ruined by the fags and booze who even now leads ‘the sort of life that parsons preach against’.

The story begins with the Pooterish Mr Josser in his office at exactly four thirty p.m. on Friday the 23rd of December 1938 – the very moment of his retirement. Amidst the valedictions of his colleagues, the author delivers the first of many subtle ironies in the novel as Josser receives his marble retirement clock to be then told by the proprietor of Battlebury & Sons “the rest of your time’s your own”. The novel touches on the lives of all the residents of 10 Dulcimer Street, with a number of sub-plots intertwined throughout, but there is no central character or single continuous plot.

The narrative is held together however by the activities of young Percy Boon, who begins his nefarious career respraying stolen cars, then turning his hand to stealing the cars himself, and finally, through a concatenation of misadventures with a peroxide blonde, to the capital offence of murder. Percy, with knuckledusters and his cosh, is incapable of making it as the smallest of small time criminals; he can’t even touch up a stolen car in a back street lockup without leaving a trail of incontrovertible and incriminating evidence behind him like a treasure hunt. The grasping, spectacularly ineffective solicitor (a classic Dickensian touch) who interviews Percy in prison leaves the cell shaking his head in disbelief at the true state of Percy’s ignorance:

The narrative is held together however by the activities of young Percy Boon, who begins his nefarious career respraying stolen cars, then turning his hand to stealing the cars himself, and finally, through a concatenation of misadventures with a peroxide blonde, to the capital offence of murder. Percy, with knuckledusters and his cosh, is incapable of making it as the smallest of small time criminals; he can’t even touch up a stolen car in a back street lockup without leaving a trail of incontrovertible and incriminating evidence behind him like a treasure hunt. The grasping, spectacularly ineffective solicitor (a classic Dickensian touch) who interviews Percy in prison leaves the cell shaking his head in disbelief at the true state of Percy’s ignorance:

‘Elementary education. What does the taxpayer get for it? What does anyone get for it? What do teachers do?’

Even when inside on a murder charge, Percy is still dreaming of pulling off the big job that will allow him ‘one day (to) have my own racing team – Boon Specials’. He and Doris (Mr Josser’s daughter upon whom he has designs) would live in their own house with a garden out in the suburbs and join a posh tennis club. In fact, Doris has made it clear that she wouldn’t touch him with a bargepole, and anyway people of their class would be as welcome in a suburban tennis club as a masseur with leprosy. In one his reveries of wish fulfilment he writes about his career as a criminal and his experience ‘inside’ in the world of True Crime – ‘Fleet Street Discovers New Crimewriter’. He can hardly spell his name.

Mr Puddy, the curve of whose decline in employment status intersects with the upward trajectory of Percy Boon’s meagre ambitions in the criminal underworld, has a cluster of gastronomic habits which shock us into a realisation that junk food – like the futility of elementary education – is not an entirely modern phenomenon. Mr Puddy when not eating (and he ‘was almost always at it’), dreams about eating:

‘(he) … liked his chop or steak, his boiled suet roll or treacle pudding … a whole cold pie followed by bread and jam, bread and syrup, or bread and fish paste … the recurrent sadness of his single life was that boiled puddings no longer appeared on the table’.

He plans his repasts the way a general prepares for military engagement, surveying the terrain and marshalling his forces in strict battle order according to their operational, tactical, and strategic significance: ‘shovelling rashers of bacon into a pan … he had broken two eggs into a cup … on one end of the table bread butter and marmalade set out … and the milk bottle standing. He had taken down the biggest teapot so that there should be no danger of a shortage and he was about to settle down … for the next two hours’. For him the thought of starving to death is worse than that of being bombed by the Lutwaffe, and so as war is declared he conjures up a heady putative hoard of foodstuffs for the duration:

6 tins condensed milk.

8 lbs sugar

3 packets Quaker oats

2 marmalade

2 Jam

2 Bovril

6 Tins salmon

2 Pineapple (tins)

2 peaches (ditto)

3 lbs rice

1 tongue (Lazenby)

As Glinert observes, it would scarcely last him a week and, regrettably, the wall-mounted vessel encompassing this gallery of delights slips her moorings, thus precipitating one of the novels’ finest comic moments. When the medium Mr Squales trips over a stray tin of salmon on the stairs, the adenoidally challenged Puddy explains apologetically:

“You drod od a sabbod”

“On a what?” Mr Squales exclaimed.

“Od a tid ob sabbod. A Sailor Slice.”

Life goes on: Mr Josser retires from his city office and wants to remove to the country; Doris Josser, the daughter of the house, leaves home to live with her posh (well, posher) friend Doreen; Connie’s Mayfair night club is raided (fourteen days without option); pursued by the threadbare Squales, the landlady Mrs Vizzard consoles herself with the thought that ‘it wasn’t as though he were a failure … he just hadn’t succeeded yet’ and succumbs to his manifestly romantic, but latent materially conniving, advances – at least until he abandons her (almost on the eve of their wedding) for the wealthier Mrs Jan Byl, one of his clients whom he meets at a séance.

Mr Puddy just puddies along from one low status job to the next, never abandoning his briefcase, a relic of his better days as a dairy manager and a badge of his former respectability (in which he now bears his array of, mostly tinned, delicacies to and from work). Ted, Mr Josser’s married son, personifies mediocre respectability: on becoming manager of the Co-op hardware department – one of Orwell’s ‘five-to-ten-pound-a-weekers’ – he thinks his six pound five a week at thirty-four is as good as it gets (Doris gets four as a typist and Josser Senior two for his pension). Through the charlatan Squales, we are introduced to a minor constellation of astralists: the South London Spiritualist Movement and the South London Psychical Society as well their transpontine rivals, the Finsbury Park based North London Spiritualist Club and North Kensington Spiritualist Union.

We meet the harmless and rather ineffectual German spy Dr Otto Hapfel (based on the real life espionage agent, Hans Wilhelm Thost) who is astonished to find English women wearing their hair short, smoking in public, and even arranging their own marriages; in an ingenious reversal of Shaw’s Pygmalion plot he arranges to take not English but ‘High Cockney’ lessons from an ageing actress in order to pass himself off as a Britisher. It could almost be Connie Coke herself, forlornly attempting to impart the rudiments of cockney patois:

‘ “Don’t move your lips, or your tongue or your jaws, just say it. Try this one: “Wozzatime”

“What is the time” Dr Hapfel repeated carefully.

‘Again: “wozzatime”’

“Whatistthetime” Dr Hapfel intoned slightly faster than before.

The old actress sighed.’

There are deliciously wry observations on London’s petty snobberies of place: ‘Mayfair … poky little mansions all squeezed up side by side … (but) the address W1 excuses (it)’; for Doris ‘it was bad enough living anywhere south of the river. She knew the solution of course’ – and so is enticed into moving with Doreen Smyth into a flat in Hampstead – perhaps not quite Hampstead, actually as it turns out, rather a kind of wilderness at the back end of Chalk Farm reached by a crowded tube journey and a dreary bus ride; and not quite a flat either, more a converted attic space, approached by a steep ascent on a towering ‘zigzagged cast iron fire escape’. To Doris, Camden Town is a disappointment and ‘appears exactly the same as the Elephant and Castle on her side of the river’. In another of the novel’s pointed ironies of reversal the disorientation of the Southsider marooned on the north bank is revealed: the view from her flat in Adelaide Road overlooking Primrose Hill (‘the tops of the houses were sharp and regular, it looked as though a child had cut them out of creased cardboard’) makes her homesick.

The novel’s sense of period and place is acute on London particular: the bustle and cosiness of the crowded City pubs at five o’clock on a winter’s day; the dreary boneshaking tram ride home to Kennington, via the Embankment and Lambeth; the invisible fault line of social status between the pretentious Smyths and the down-to-earth Jossers. A number of scenes are drawn to perfection: the still untamed wildness of Wimbledon Common; the peculiar charm, and relative extravagance, of The Medusa Private Boarding Establishment on Brighton seafront ‘where the food was famous’ (milk pudding on Fridays!); Collins paints an exquisite lyrical cameo of the young couple (Doris and her not-quite-fiancé-yet Bill) in a flaming, sparkling sunset at Waterloo Bridge, thirty years before the idea occurred to Ray Davies.

The theme of food recurs, and there is an almost Zolaesque relish in the depiction of detail: the ‘soapy yellow’ texture of Mr Puddy’s over-processed cheese; Grosvenor pie with ‘… a hard-boiled egg, like a yellow eye … in the middle of it’; the ‘long sticky kiss’ of two slices of bread and butter being prised apart; herrings ‘… small oily mermaids (reduced to) only tiny white fragments left clinging to the ingenious spring framework of fine bones’. Writing in 1836 Dickens had the irrepressible Sam Weller sum up Whitechapel as ‘Poverty And Oysters’; almost exactly a century later, Collins did the same for Kennington – ‘Gentility And Fish Paste’; prior to the séance beginning, as the plates are handed round at tea amongst the petit-bourgeois Kenningtonians of the South London Psychical society, the eternal question is posed: “fish paste or sandwich spread?” To our astonishment even Mrs Jan Byl, the plummy Knightsbridge widow, tucks in.

London Belongs To Me marks roughly the midpoint chronologically, as well as quantitatively of Collins’s output and is his best known novel. Running to seven hundred pages there is no sense that this is a saga, nor does it feel padded out. On the contrary, another author would have made this into a trilogy, and one could easily have made an entire book out of either Mr Puddy’s culinary and occupational disasters, or of Percy Boon’s pipe dreams and depredations in the underworld, or the antics of Mr Enrico Qualito (aka, the slinking Squales) philandering amongst the (occasionally affluent) lonely spinsters and derelict widows of the spiritualist unions.

Collins sees London undergoing constant renewal: ‘the Huguenots, the Jews … the French and Italians in Soho, Chinese in Limehouse, Scotsmen in Muswell Hill, the Irish round the Docks’. London is not just the delimited space where social transactions take place, London is also the people who live and work there; but mainly live there for those suburbanites, the ‘demi londoners’ who merely work there emerge each morning to simply to ‘play at being Londoners again’.

Christmas 1940, and ‘the war hasn’t so much as touched Dulcimer Street yet. Perhaps never will.’ But with the shortage of manpower, Mr Josser is now back at Battlebury and Son. Sheltered and contented amongst the shelves of silent ledgers (‘E to Egg-’) at Creek Lane EC2; it is if he’d never been away. ‘This is where I belong’ he told himself, an almost aboriginal instinct for the inseparability of people and place surging within him: ‘I belong to London. And London belongs to me’.

Bibliography

Titles by Norman Collins

- The Facts of Fiction – 1932

- Penang Appointment – 1934

- The Three Friends – 1935

- Trinity Town – 1936

- Flames Coming Out of the Top – 1937

- Love in Our Time – 1938

- I Shall Not Want – 1940

- Anna Collins – 1942

- London Belongs to Me – 1945

- Black Ivory – 1948

- Children of the Archbishop – 1951

- The Bat that Flits – 1952

- Bond Street Story – 1958

- The Governor’s Lady – 1968

- The Husband’s Story – 1978

- Little Nelson – 1981

Charles Dickens, The Pickwick Papers (1836)

Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet (1887)

– , The Sign Of Four (1890)

George Orwell, Keep The Aspidistra Flying (1936)

George Orwell, Coming Up For Air (1939)

All rights to the text remain with the author.