Rachel Lichtenstein

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

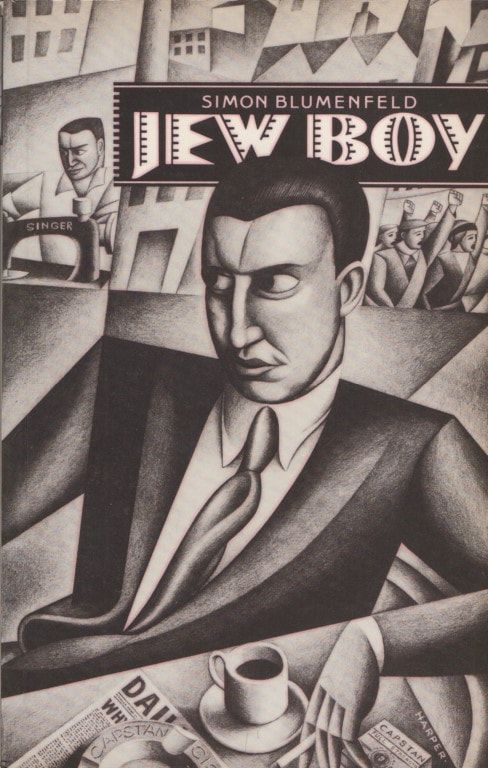

When Jew Boy was first published in 1935 it caused a sensation. There was an enormous amount of controversy about and interest in the book, partly because of its deliberately provocative title and forceful political message but predominantly for its gritty depiction of working-class Jewish life in Whitechapel.

Back then the majority of the population knew little about the religious practises and daily lives of the poverty stricken Jewish community who occupied much of the area. The Jewish East End was an entirely closed world to outsiders, and one which had not been written about in British fiction since Israel Zangwill published his bestselling novel back in 1892, Children of the Ghetto.

It was a revelation to people to learn about the place and its inhabitants through reading Jew Boy. They were intrigued by the detailed descriptions of the Jewish festivals and celebrations. Amazed to learn about the complex network of self-supporting interconnected Jewish societies, clubs, theatres and institutions. Shocked to hear of the terrible working conditions in the tailoring sweatshops where thousands toiled up to eighteen hours a day.

It was a revelation to people to learn about the place and its inhabitants through reading Jew Boy. They were intrigued by the detailed descriptions of the Jewish festivals and celebrations. Amazed to learn about the complex network of self-supporting interconnected Jewish societies, clubs, theatres and institutions. Shocked to hear of the terrible working conditions in the tailoring sweatshops where thousands toiled up to eighteen hours a day.

Jew Boy became an instant bestseller, which was widely reviewed and highly praised. For most readers it provided a window into an unfamiliar and exotic milieu.

For Simon Blumenfeld there was nothing mysterious or strange about the pre-war Jewish East End. It was a place he knew intimately and many elements of Jew Boy are undoubtedly autobiographical. Much like Alec, the protagonist of his novel, Blumenfeld was a second-generation immigrant Jew who had been born and raised in Whitechapel. He was a bright student, who dreamt of becoming a writer but like most young Jewish men living there during this period, his career choices were severely restricted by the depressed economic environment around him. After winning a coveted scholarship to the local grammar school, Blumenfeld had to leave before completing his studies to help provide for the family. His first job was as a cap-maker, (like his father) then later he became a presser, in the sweatshops he portrays so vividly in Jew Boy.

The east London of the 1930s was not the same place described by Zangwill half a century before. The younger generation were a completely different breed to their Yiddish speaking orthodox parents. They had an entirely different set of concerns. Many were dissatisfied by the confines of the Jewish ghetto. They didn’t want to become tailors, furriers, cap makers, pressers, cabinet-makers or taxi drivers. They dreamt, like Blumenfeld, of other more satisfying careers. I imagine Blumenfeld felt resentful towards his parents about having to leave school early and abandon his dream. There is a great deal of anger expressed in Jew Boy about the limited opportunities available for poor Jewish and gentile working-class young people during that period. There is also a realistic portrayal in the novel of the integration of different communities that was taking place in the area during that time, predominately between young Jews, gentiles and Irish migrants. My own father is typical of this generation. He was born in Whitechapel, to first generation immigrant parents, married a gentile woman, anglicised his surname and moved away from the area.

Another central feature of the novel, radical left-wing politics, was part of the landscape of Blumenfeld’s early life. In Harry Blacker’s 1993 film Eastendings, Blumenfeld reminisces about the furious debates he regularly witnessed on the pavements of Whitechapel as a child: ‘there were more Communists and anarchists outside the synagogue arguing about the state of the world than there were inside praying. The activity was all out there, with these people milling around talking politics.’ This energetic street-life has been perfectly captured in Jew Boy in a number of engaging and lively chapters that focus on Alec’s fervent attachment to Communism.

I have recently discovered members of my own family were heavily involved in socialist politics during the same period. My grandfather’s uncle, Yisroel Lichtenstein, was a prominent member of The General Jewish Labour Bund (in Lodz, Poland), a secular Jewish socialist party, which sort to unite all Jewish workers in the Russian Empire. Yisroel came to visit my grandparents in their Whitechapel home in Brick Lane in 1931, whilst on a fundraising tour for the party. My grandfather asked him if he would like to go and see the sights of London; Big Ben, the Tower of London. “Take me down to the docks,” he replied, “I want to see how the workers of England live.”

This response could have been lifted directly from the pages of Jew Boy – which is a truly proletarian novel and the first literary work to depict in detail the radical, turbulent, politicized and divided Jewish East End of the 1930s.

Many of the scenes described in Jew Boy would have been familiar to my paternal grandparents, who met, married and settled in Brick Lane, after arriving from Poland as refugees in 1925. Much like Alec in the novel, they were poor Jews, who weren’t particularly observant but had rich cultural and social lives. My grandfather (who was also called Alec) was one of the founding members of the Literarishe Shabbes Nokhmitogs, The Friends of Yiddish literary group, which had been established in 1936 by the Yiddish poet Avram Stencl. My grandparents attended the Yiddish theatres, frequented the dance halls, cafes, libraries and societies which are so personally described in Jew Boy and mingled with the poets, radicals, artists, boxers, musicians, politicians and workers who lived in the area at the time.

After the war, like many others from that community, they moved from the bombed out streets of east London to Westcliff, or Whitechapel-on-sea as many called it. Their new home in Essex became a refuge and meeting place for the characters they had met in the former Jewish East End. Half remembered details about meeting these lively people when I was a child, along with hearing my grandparent’s stories about the artistic and vibrant atmosphere of Jewish Whitechapel, fuelled my fantasies about the place.

I moved there aged nineteen, filled with romantic notions about the past. I spent years living and working in the area, tracing and recording the stories of the rapidly diminishing Yiddish speaking community who still lived there. I met extraordinary characters, like the great east London historian, Professor Bill Fishman, and the tailor and Yiddish singer, Majer Bogdanski, who both looked back at a disappearing world with some nostalgia and longing. I devoured the literature that described the former Jewish quarter; the novels of Israel Zangwill, Wolf Mankowitz, Alexander Baron and Emanuel Litvinoff along with the plays of Bernard Kops and Arnold Wesker. Although these works do not shy away from talking about the tough living and working conditions that existed in the area before the war, they all have nostalgic or romanticised elements, which are almost completely missing from Simon Blumenfeld’s hard hitting debut novel Jew Boy.

The tone of the book is set within the opening page, where we find Alec, a twenty-three year old tailor, being roughly awakened by his mother, who is screaming at him to get out of his ‘stinking bed’ and into the workshop. She is not the stereotypical dotting Yiddishe momma of East End folklore but a furious, disappointed woman, who ‘shouts violently all the time.’

After dressing hurriedly, Alec gulps down some tea and leaves the rundown flat for a windowless basement five minutes walk away, where he is confronted with the familiar and depressing scene of ‘a dozen automata bent over the garments, sewing, machining, pressing, at top speed.’ The relentless physical working day is described in minute detail, as are the cramped and unhygienic conditions ‘with the steam and the sweat and the boss shouting like a madman.’ After years spent hunched over the benches, Alec feels his mind has been ruined by the ‘unrelenting drudgery’ and physically he has become ‘almost like a cripple, a limp, screwed-out rag’. Returning early from work he catches his mother fooling around with a heavy set middle-aged man and after a violent argument Alec abruptly leaves the family home and finds new lodgings nearby.

Although Jew Boy is often described as the definitive east London Jewish novel of the period, much of the action takes place in other parts of the metropolis and some of the central characters are not Jewish. The strongest and most rounded character is a working-class gentile woman called Olive, who is introduced to readers whilst on a date with Alec’s womanising former school friend, Dave, in one of a number of scenes in the book set in Hyde Park. After canoodling with Dave in dark corners, Olive starts to panic when she realises the late hour and rushes back to her lodgings in Edgware Road. After knocking repeatedly on the door of the ‘dirty little dwelling’ where she lives, a ‘savage toothless bitch’ eventually opens the window and throws the contents of a chamber pot over Olive, whilst calling her a slut and telling her to come and collect ‘her filthy rags in the morning.’ ‘Feeling terribly alone’ the dejected Olive takes the night bus with Dave back to Whitechapel. They turn up at Alec’s bedsit and persuade him to let Olive stay the night.

The next chapter opens in Stepney Green where thousands of Jewish protestors are massing for a demonstration to Hyde Park remonstrating against the persecution of Jews in Germany. During the 1930s there were numerous anti-Nazi demonstrations in London. The largest took place on 20th July 1933, when 50,000 Jews marched from the East End to Hyde Park. Blumenfield dedicates a whole chapter to this event, which is portrayed from Alec’s perspective at the back with ‘the reds’. As the Jewish demonstrators pass through the city, anti-Semitic and anti-communist abuse is hurled at them from bystanders: “Damn’ Jews! They’re all Communists, reds – revolutionaries!”

When the march eventually reaches Hyde Park ‘another thirty thousand Jews’ are waiting for them. Exhausted, Alec retires to a Lyons teashop nearby where he bumps into another old friend, Sam. As the two men walk back towards the park, ‘the dark masses of people thinning out behind them’, they swap stories, discovering they now share the same political orientation along with a great passion for high culture. Alec is delighted to have found someone with whom to attend lectures, concerts and meetings.

The plot of the novel weakens slightly from this point onwards, as a series of highly unlikely meetings on West End streets occur. On his way home from the march, Alec bumps into Dave, who tells him Olive is now working as a live-in daily at his family home. Despite the low wages of most east London Jewish families at the time, having a gentile live in maid was a common occurrence, particularly for observant Jews who needed a Shabbas goy to light the fire for them and perform other menial task they were not permitted to complete because of religious restrictions.

On the morning of the ‘Black Fast’, Olive rises early to help Mrs Bercovitch (Dave’s mother) prepare the feast to be consumed after the Kol Nidre service. ‘When the sun was down low at the end of the day, she had to put the soup on the stove, the roast in the oven. On the table, the decanter of spirit and kummel, one Dutch and one pickled herring, green olives, bread and the horseradish sauce.’

Mr and Mrs Bercovitch leave for synagogue, dressed in their finest clothes but Dave stays behind, claiming to be unwell. Worried about her son, Mrs Bercovitch returns early to find Olive ‘crying bitterly in the corner.’ Her clothes have been torn and there are ‘red marks like scratches across her chest.’ After being the victim of an attack, possibly a rape, Mrs Bercovitch calls Olive ‘a whore’ and throws her out of the house.

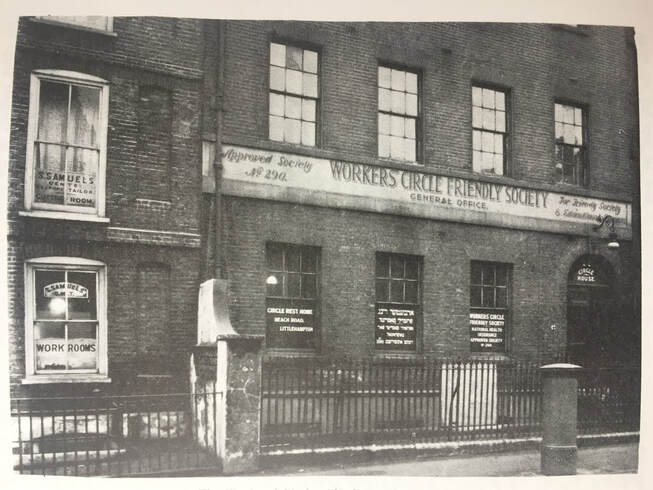

In the meantime Alec and Sam walk to the Workers’ Circle (Arbeiter Ring), which was the central meeting place for working-class left wing activism in east London during the 1920s and ‘30s. The Circle had originally been formed as a socialist friendly society in 1909 by Russian immigrant cabinet makers, to protect those in the community who were sick or unemployed. Over the years it developed into a cultural and social club as well, with an emphasis on self-improvement and socialist politics. In 1924 the society took over two buildings in Great Alie Street (just off Commercial Road), which became known as Circle House. It consisted of a large clubroom, meeting rooms and a concert hall. Blumenfield paints a wonderful portrait of the political make-up and great range of activities available there in the 1930s. When Alec enters the crowded clubroom ‘the air was thick with steam from the urn and a bluey-grey fog of tobacco smoke.’ A few old men were playing chess and dominoes in the corner and at the back of the room sat a man with a beard reading the Jewish anarchist paper Freiheit. Alec ordered some supper at the canteen; herring, black bread, lemon tea, and sat amongst the other Marxists, poets, Communists, writers, Labour Party members, anarchists, Bundists and Zionists gathered there.

Later in the evening Alec attends a classical concert in the building where a ‘beautiful blonde’ in the audience distracts him. During the interval he buys her a cup of tea, which she snottily accepts from the ‘penniless, skinny little Jew tailor.’ Alec fantasises about her during the second half but she leaves before the end. Sexually frustrated and consumed by desire he wanders alone around the West End, tempted by prostitutes, angry and dejected.

Dave (who has moved into Alec’s bedsit by this time) continues to date numerous women, with semi-disastrous consequences, before being forced into an arranged marriage with a wealthy older Jewish woman. The wedding scene takes place in a typical, overcrowded Whitechapel synagogue. Blumenfeld intimately describes the different characters of the community, from the ‘jabbering’ women sat in the balcony, to the ‘greybeards’ arguing about ‘what rabbi Akiba said’ to the youngsters discussing boxing, dogs and horse racing. Throughout the service ‘the throbbing dynamo of conversation rose above the organ.’

Alec’s luck temporarily changes when he meets a nice sensible Jewish girl called Sarah on a Sunday ramble in the countryside. The most affectionate description of the former Jewish East End occurs when he visits her Whitechapel home for Sunday lunch. Inside the small flat he listens to Sarah sing Hebrew melodies around the piano, eats a wonderful home cooked kosher meal and plays chess in the parlour with her brothers. By the end of the evening he has decided Sarah is ‘just the girl for him.’

Soon after Alec accompanies Sarah to visit her sister in the suburbs of Barnes, where she lives in a ‘clean semi-detached villa’ with a ‘tall and fair’ gentile college professor. A comical scene follows as Alec becomes determined to ‘out’ Sarah’s sister in front of her posh gentile lunch guest and ‘let the whole neighbourhood know she is Jewish.’ Although Alec is more than aware of the limitations of Jewish East London, with all ‘its faults, its turbulent excitable people and habits,’ he cannot understand how ‘any intelligent person could exchange that for the anaemic narrow-minded dreariness of suburbia.’

As the relationship between Sarah and Alec progresses he pushes her into coming away with him for the weekend but she fails to turn up. After sobbing into his pillow, Alec argues with a poet and his cronies at the Workers’ Circle then wanders around the West End again like a lost soul. On the street he bumps into Dave and Olive. Then in a very hard to believe double coincidence, Dave’s new brother-in-law also appears on the same street corner and Dave quickly dumps Olive on Alec. By now Olive is earning a living as a West End prostitute, which is told to the reader in a very matter of fact way. Olive invites Alec back to her flat, where he loses his virginity and after that he continues to see Olive ‘pretty frequently.’

Alec regards Olive as ‘another who had never had a decent break from life’ like him. Soon they move in together, finding a bed-sit ‘on the top floor of a dirty three-storeyed house in North-east London.’ Olive starts waitressing in a café and Alec continues to work as a tailor in Whitechapel.

After saving for months, the couple treat themselves to a day trip to Southend-on-Sea. Disembarking from the train they breathe ‘in the keen salty air’ and take a stroll along the pier. Alec tells Olive he hasn’t felt so fit and well for years. After hiring some deck chairs, Olive happily exclaims, “If there were a heaven, it must be some place like this, where you could just lounge about…. and do nothing for hours, and hours and hours.” They spend the last of their savings on fish and chips, a ride on a trolley bus and a cruise on the Mary Ann: ‘Out to the ocean-going liners, and back for sixpence.’

I expect my own grandparents took a very similar day trip from Whitechapel to Southend in the 1930s. I remember my grandfather saying to me that he still felt like he was on permanent holiday, even after living there for over forty years.

Back in Whitechapel life is worse than ever for Alec after the controversial Bedaux system is introduced to his workshop, forcing the workers to ‘work twice as hard for the same money.’ Alec instigates a strike, making his boss determined to lay him off as soon as an opportunity arises.

Life continues in an unchanging pattern. Although they can barely afford the rent, Alec is desperate for culture and encouraged by Olive, he attends a symphony concert in the West End. Standing happily amongst the chattering crowd, ‘drunk’ with the ‘wealth of unaccustomed beauty’ he relishes every moment. In the bar he bumps into the blonde from the Workers’ Circle and although he feels terribly guiltily, he leaves with her. She takes him to Perelli’s – a cellar bar filled with ‘bohemians, tobacco smoke and the clattering of plates.’ Alec is nauseated by the place with its ‘fake intellectuals, fake Communists and fake artists.’

The girl invites him back to her beautifully furnished flat nearby. Alec cannot believe the size of the place and soon becomes filled with jealousy and a repressed hatred for the girl and her privileged lifestyle. They start to argue and she accuses Alec and ‘his people of only being guests here.’ Fuming he tells her about his father, ‘an emigrant running away from the Czar’s hell’ who came to London a pauper, slaved for twenty years in the workshops, ruined his health and died before he was fifty. The girl only laughed at him. Feeling murderous towards ‘the beautiful bitch’ he ‘kissed her fiercely, biting her lips wildly, trying to dominate her, to make her feel him and accept him; and she submitted, yet he felt that aloofness all the while.’

He returns home, smelling of perfume and poor Olive sobs herself to sleep, begging him not to leave her. Soon after she falls pregnant. Determined not to drag ‘another soul into this filthy world’ she tries to get rid of the baby by taking boiling hot baths and lifting heavy weights but ‘the seed still flourished in her womb.’ Eventually she has an illegal abortion. Much like the sex scenes in the book and the probable rape scene, all details are left to the reader’s imagination. Olive stays in bed for three days, ‘her face drained of blood’ before returning to work. She doesn’t mention the baby or the abortion to Alec.

In November, Alec is given notice to quit the workshop and fails to find another job. ‘He had no head for books now, the problem of living took up all his time, worrying about the future; the terrible, uncertain, ever darkening future.’ Grim scenes follow as Alec joins the ‘long grey line’ of men at the Labour Exchange, with ‘tired pale faces, stooping shoulders and threadbare coats.’

As the weeks of Alec’s unemployment drag on Olive tries to get him interested in working the markets. He visits an old friend who has a stall in Petticoat Lane but after spending a day helping out: ‘rolling and unrolling fabrics, arranging and re-arranging, all for a lousy few pence’ Alec returns home tired and dejected with ‘all his hunches pricked flat.’

The next day he returns to Whitechapel, for the first time since he moved in with Olive. After a trip to the reference library he wanders aimlessly towards Aldgate, passing the Odessa Yiddish restaurant, where he is drawn inside by an ‘overpowering gust of appetizing smells.’ Inside a matronly woman serves him a Russian Jewish feast. Feeling nostalgic he makes his way towards his mother’s house but finding her to be out he returns to Whitechapel High Street, ‘the broadest pavement in the world’ where he reminisces about promenading there in his smartest clothes, ‘chasing girls, snatching kisses.’ He stops outside Gardiners Corner and talks to a group of taxi drivers about potential work, only to find the taxi business is ‘all played out’ as well.

Driven nearly to the point of despair, Alec wanders aimlessly around the city, eventually making his way to Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park, where he listens to a black activist called Jo-Jo speak about the problems affecting workers all over the world. Jo-Jo helps Alec see that his miserable situation is part of a wider global problem, he talks about the persecution of blacks in Africa, the murder of the Chinese, the abuse of women in the South of America. With his ‘eyes lit up, as if a flame had suddenly crackled into life,’ Jo-Jo tells Alec about his recent visit to Russia, where he was treated as an equal, ‘like a comrade.’

In the most romanticized domestic scene in the whole novel Alec visits Jo-Jo’s flat, in ‘a tall, dark-grey block of tenements.’ Inside the welcoming front room he sees ‘a broad negress’ with a face that radiated ‘warmth and life’ sat beside a fire, with a chubby baby on her knee and a small boy playing on the floor nearby. Alec plays with the children and for the first time contemplates how nice it would be to have one of his own.

Walking home, inspired by Jo-Jo, Alec decides to emigrate to Russia. The ever patient Olive reluctantly agrees to accompany him there but the dream, like so many others, is ‘pricked flat’ when the Russian consulate rejects his application.

The final scene in the book takes place back in Hyde Park, during another anti-fascist demonstration. During the march Jo-Jo is arrested and Alec is ‘violently brushed into the gutter by the powerful impact of a horse.’ At this moment Alec decides it is ‘criminal to stay out [of the Party] any longer.’ The book ends with the rallying cries, “freedom for the oppressed” and “No Peace until the disinherited regain the Earth!” Alec seems to finally find salvation in revolutionary politics.

This ending seemed most unsatisfactory to me as a modern reader until I was reminded by the writer Ken Worpole (who has written a brilliant introduction to the new edition of Jew Boy) of the dangers of having a condescending attitude to the past in the present. He pointed out that ‘we really do not know what it feels like now to have lived in that time, to feel the very real threat and danger of fascism. There was a great pressure both close to home and on a global scale. People really did feel that passionate about Russia and Communism.’ This sentiment is backed up by Rabbi Lionel Blue, who also appears in the film Eastendings, where he talks about how idealistic the majority of young Jews were about communism before the war, describing the depths of their passion as being akin to ‘a religious movement’.

In my opinion Jew Boy is not as strong a novel as Blumenfeld’s next book Phineas Kahn: Portrait of an Immigrant (published in 1937), which is a marvellously written fictionalised account of his wife’s family’s story of migration from Russia to East London.

There are weaknesses in the plot of Jew Boy, but despite this the novel is extraordinarily rich and there is still nothing else quite like it. The Jewish Whitechapel of the 1930s Blumenfeld describes, with its communists and anarchists, sweatshops and theatres, cafes and libraries, slaughterhouses and concert halls, has completely disappeared. I for one feel immensely grateful that Blumenfeld took the time and care to write about the place, which for all its problems, ‘had life and colour and throbbed with vitality.’

Her website is at https://rachellichtenstein.com/

References and Further Reading

Harry Blacker, Just Like It Was: Memoirs of the Mittel East, Vallentine Mitchell, 1974

William J.Fishman, East End Jewish Radicals 1875 – 1914, Duckworth, 1975

East End 1888, Duckworth, 1988

Willy Goldman, East End My Cradle, Faber and Faber, 1940

Joe Jacobs, Out of the Ghetto – My Youth in the East End: Communism and Fascism 1913 – 1939, Janet Simon, 1978, republished by Phoenix Press, 1991

Tony Kushner and Nadia Valman (eds), Remembering Cable Street: Fascism and Anti-Fascism in British Society, Vallentine Mitchell, 2000

Rachel Lichtenstein and Iain Sinclair, Rodinsky’s Room, Granta, 1999

Emanuel Litvinoff, Journey Through a Small Planet, Michael Joseph, 1972

Phil Piratin, Our Flag Stays Red, Thames Publications, 1948, republished by Lawrence and Wishart, 1978

Raphael Samuel, East End Underworld: Chapters in the Life of Arthur Harding, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981

H. Srebrnik, London Jews and British Communism 1935-45, Vallentine Mitchell, 1995

Arnold Wesker, Chicken Soup With Barley, (play first performed Coventry, 1958)

Jerry White, Rothschild Buildings: Life in an East End Tenement Block 1887 –1920, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980

Ken Worpole, Dockers & Detectives, Verso, 1983, republished by Five Leaves, 2008

Ken Worpole’s introduction to new edition of Jew Boy published by London Books in 2011