Fran Pickering

Arnold Bennett was one of the best known writers of the early twentieth century. He wrote sympathetically and realistically about the working classes and their struggles with poverty, with a special focus on the shopkeepers and labourers of the Staffordshire Potteries where he was born.

His best known works, such as The Old Wives Tale and Anna of the Five Towns, are set in the ‘five towns’ (in reality there are six but Bennett thought five sounded better) in the Potteries where for centuries English ceramics were produced, so we tend not to think of him as a London writer. In fact he left Staffordshire when he was twenty-one and spent most of his adult life in London, apart from an eight year period living abroad.

His subject matter and writing style place him clearly in a tradition tracing back to Dickens and Maupassant, whom he greatly admired. He was despised by the aesthetic, intellectual Bloomsbury Group; Virginia Woolf went so far as to give a lecture at Cambridge in 1924 mocking the prosaic nature of Bennett’s writing and his failure, as she saw it, to imagine and recreate the inner life of his characters. Perhaps as a result he was neglected for much of the second half of the twentieth century until in 1992 the critic John Carey led a reappraisal of his work, praising his realism and focus on the lives of ordinary people, and rating him as one of the twentieth century’s most enjoyable writers.

His subject matter and writing style place him clearly in a tradition tracing back to Dickens and Maupassant, whom he greatly admired. He was despised by the aesthetic, intellectual Bloomsbury Group; Virginia Woolf went so far as to give a lecture at Cambridge in 1924 mocking the prosaic nature of Bennett’s writing and his failure, as she saw it, to imagine and recreate the inner life of his characters. Perhaps as a result he was neglected for much of the second half of the twentieth century until in 1992 the critic John Carey led a reappraisal of his work, praising his realism and focus on the lives of ordinary people, and rating him as one of the twentieth century’s most enjoyable writers.

Riceyman Steps is one of his best works – it won him the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1923. It’s the story of a Clerkenwell shopkeeper, Henry Earlforward, his successful wooing of the widow, Mrs Arb, who owns the shop next door to his secondhand bookshop, and how their mutual obsession with saving money turns to tragedy. It takes you inside the mind of a miser and makes him sympathetic and almost understandable.

Riceyman Steps is one of his best works – it won him the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1923. It’s the story of a Clerkenwell shopkeeper, Henry Earlforward, his successful wooing of the widow, Mrs Arb, who owns the shop next door to his secondhand bookshop, and how their mutual obsession with saving money turns to tragedy. It takes you inside the mind of a miser and makes him sympathetic and almost understandable.

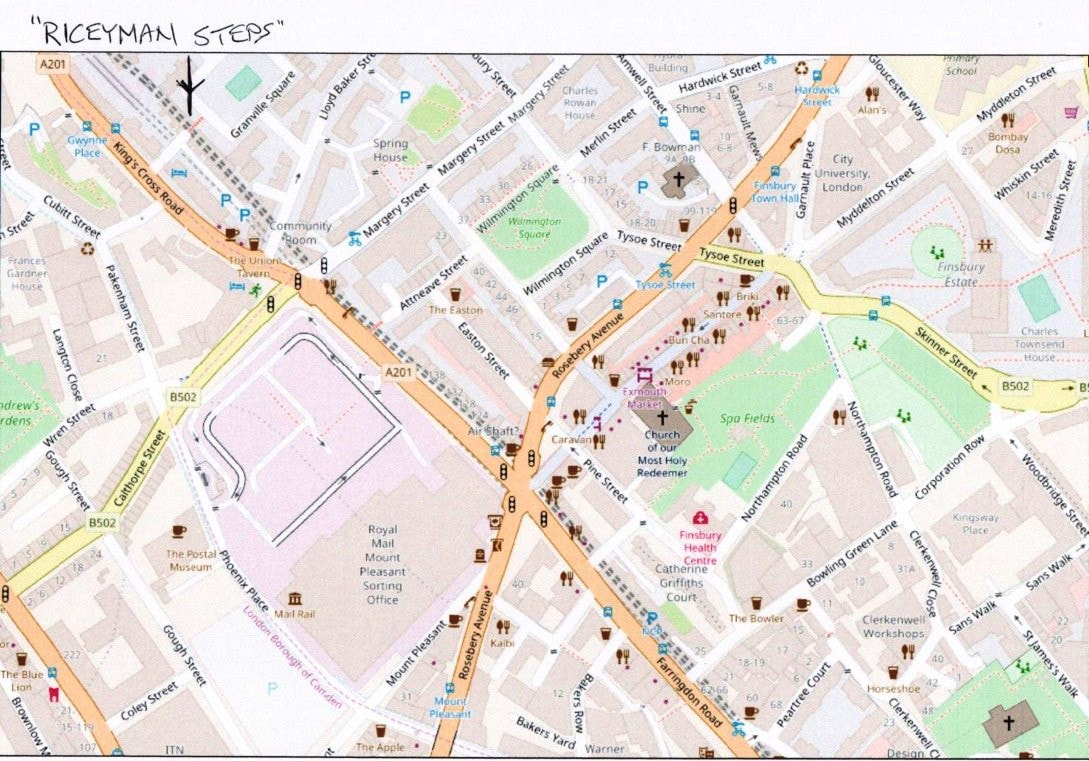

The novel is set in a specific part of Clerkenwell – the action takes place almost entirely in and around the Lloyd Baker estate, built in the early nineteenth century between King’s Cross and the Angel Islington, south of Pentonville Road. Henry’s bookshop at the foot of Riceyman Steps, the squalid room where his servant Elsie lives in Riceyman Square and the more salubrious house of Dr Raste in Myddleton Square at the upmarket Islington end of the estate, are described in detail. Though there’s no record of Bennett having a connection to Clerkenwell he must have known it intimately, as the streets and houses he describes are real ones, some of which survive unchanged to this day.

There isn‘t space here to look at more than a fraction of the places in the book, so I’ve concentrated on the detailed description of Riceyman Steps in the opening paragraphs, and the places Henry and Mrs Arb visit on their Sunday morning walk.

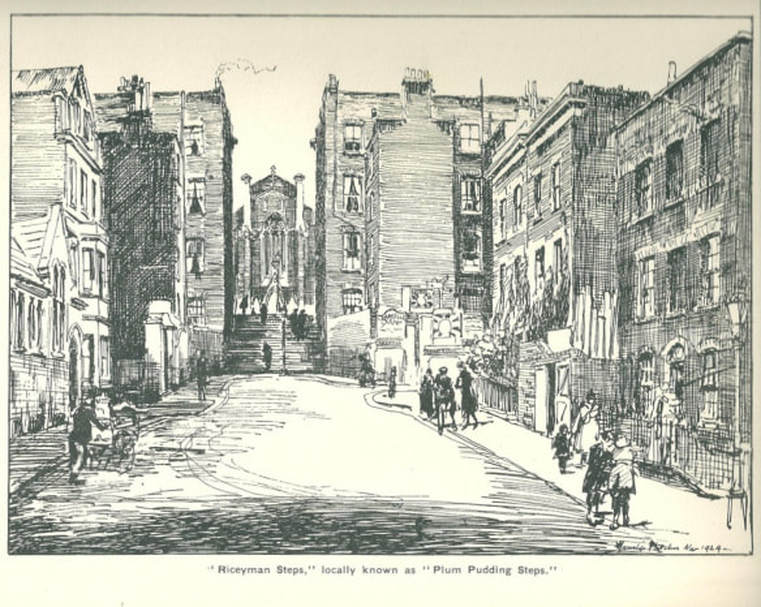

On an autumn afternoon of 1919 a hatless man with a slight limp might have been observed ascending the gentle, broad acclivity of Riceyman Steps, which lead from King’s Cross Road to Riceyman Square in the great metropolitan industrial district of Clerkenwell.

The real Riceyman Steps is now called Gwynne Place and leads up from King’s Cross Road to Granville Square (Riceyman Square in the book). The buildings at the top, the backs of numbers 33 and 34 Granville Square are just the same as in Bennett’s day.

The real Riceyman Steps is now called Gwynne Place and leads up from King’s Cross Road to Granville Square (Riceyman Square in the book). The buildings at the top, the backs of numbers 33 and 34 Granville Square are just the same as in Bennett’s day.

Riceyman Steps, twenty in number, are divided by a half-landing into two series of ten.

Actually there are fifteen steps below the half landing and eleven above, but let’s not quibble. Bennett got it nearly right, and must surely have stood on that half landing himself at some time.

The man stopped on the half-landing… Below him and straight in front he saw a cobbled section of King’s Cross Road.

Sadly, what you now see looking down is the back view of the Travelodge Hotel.

On the far side of the road were, conspicuous to the right, the huge, red Nell Gwynn Tavern, set on the site of Nell’s still huger palace.

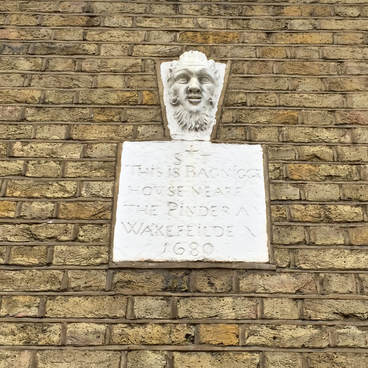

All that’s left of the Nell Gwynne Tavern is this plaque marking the site of Bagnigge House, Nell Gwynne’s summer residence. The carving on it says: “This is Bagnigge House, neare The Pindar Wakefeilde 1680”. It’s set into the wall of 3 King’s Cross Road and is obscured by the bus shelter that’s been sited in front of it.

Conspicuous to the left, red Rowton House, surpassing in immensity even Nell’s vanished palace, divided into hundreds and hundreds of clean cubicles for the accommodation of the defeated and the futile at a few coppers a night.

Rowton Houses were hostels founded by the philanthropist Lord Rowton where down and out or low paid men could stay cheaply. The first one was opened in Vauxhall in 1892. The King’s Cross one opened in 1896 and provided 678 beds. It was converted to a hotel in 1961 and the old building has now been replaced by a new Holiday Inn, which at least provides the same looming red presence, though you’ll be paying more than a few coppers a night for its rather more salubrious cubicles.

Nearer to the man…lay the tiny open space (not open to vehicular traffic) which was officially included in the title “Riceyman Steps”. At the south corner of this was a second-hand bookseller’s shop and at the north an abandoned and decaying mission hall; both of these abutted on King’s Cross Road.

None of that has survived, which is a shame as the secondhand bookshop was Henry Earlforward’s shop, where much of the story takes place. I did have hopes that the odd red brick building on the north side, mysteriously left standing when the Travelodge was built, would turn out to be the mission hall, but it was actually built in 1924 when fire destroyed the previous buildings on the site.

Riceyman Square had been built round St Andrew’s in the hungry forties. It had been built all at once, according to plan; it had form. The three-storey houses (with areas and basements) were all alike, and were grouped together in sections by triangular pediments with ornamentations thereon in a degenerate Regency style.

I think I’ve caught Arnold out here. Those pediments are typical of houses on the Lloyd Baker Estate, built between 1820 and 1840. They line neighbouring Lloyd Baker Street and Lloyd Square, now gentrified almost beyond recognition. But the houses in Granville Square aren’t in the typical Lloyd Baker style. They were the last to be built, in 1839 and standards had slipped. The pediments which Bennett describes were never there.

While the rest of the Lloyd Baker Estate has now become gentrified and fashionable, Granville Square was bought by Islington Council in the late 1970s and the houses converted into flats.

St Andrew’s Church had architecturally nothing to recommend it. The churchyard was a garden flanked by iron rails and by plane trees.

St Andrew’s (actually St Phillip’s) stood in the centre of Granville Square until 1936 when it was demolished, probably to nobody’s great regret. The churchyard garden hasn’t changed.

I was hoping to find some interesting remnants of the Clerkenwell Henry and Mrs Arb saw on their Sunday walk but there’s not a lot left.

In a few minutes they were at the corner of a vast square – you could have put four Riceymans into it – of lofty reddish houses, sombre and shabby, with a great railed garden and great trees in the middle and a wide roadway round.

“Look at that,” said Mr Earlforward eagerly, pointing to the sign. “Wilmington Square. Ever heard of it before?”

I’m not sure why we should be so impressed with Wilmington Square, but anyway, here it is.

Coldbath Square easily surpassed even Riceyman Square in squalor and foulness; and it was far more picturesque and deeper sunk in antiquity, save for the huge awful block of tenements in the middle.

I was looking forward to the squalor and antiquity of Coldbath Square, but it’s all been swept away or tidied up.

They were passing through a narrow, very short alley of small houses which closed the vista of one of the towering congeries of modern tenement-blocks abounding in the region. The alley, christened a hundred years earlier, “Model Cottages”, was silent and deserted in strange contrast to the gigantic though half-hidden swarming of the granite tenements. The front doors abutted on the alley without even the transition of a raised step.

Another disappointment, as Model Cottages is now full of contemporary houses. I did find a doorway which might be the one where Mrs Arb borrowed a copy of the News of the World to check her advertisement, though.

St James’s on Clerkenwell Green is almost unchanged.

They got to the quarter of the great churches.

“Would you care to go in?” he asked her in front of St James’s. For he desired beyond almost anything to sit down.

“I think it’s really too late now,” she replied.

But St John’s Priory Church was not so fortunate.

There were no seats round about St John’s. Mr. Earlforward stood on one leg while Mrs. Arb deciphered the tablet on the west front.

‘“The Priory Church of the Order of St John of Jerusalem, consecrated by Heraclius, Patriarch of Jerusalem, 10th March 1185.” Fancy that, now! It doesn’t look quite that old. Fancy them knowing the day of the month, too.’

I found the tablet, but now it also records the destruction of the church in 1941.

He was too preoccupied and tortured to instruct her. He would have led her home then; but she saw in the distance at the other side of St John’s Square, a view of St John’s Gate, the majestic relic of the Priory. Quite properly she said that she must see it close.

St. John’s Gate was built in 1504 as the entrance to Clerkenwell Priory. It was heavily restored in the nineteenth century so little of the stone facade is original but it is still an impressive sight and was chosen to represent Islington for the 2012 London Olympics.

Riceyman Steps, with its mundane setting for an extraordinary romance between two very unusual people, still speaks to us today. And as for Clerkenwell, nowadays it has regained the fashionable position it once held before it fell into the grinding poverty that Bennett portrays. London is a city of ups and downs, success and failure, riches and poverty, and no one knew that better than Arnold Bennett.

Fran Pickering is the author of the Josie Clark in Japan murder mystery series. She also blogs about London and this entry is an expanded version of her blog about Riceyman Steps.

All rights to the text remain with the author. All photographs taken by Fran Pickering and posted with her permission.