Gregory Woods

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

In the first half of Neil Bartlett’s novel about gay men Ready to Catch Him Should He Fall, London is not named. Nor are any of its streets, squares, parks and other locations. But, come to think of it, the people are not named either. For the purposes of this narrative, anonymity is a condition of existence. Each character is given a designation that is both individually distinctive and archetypally representative: O, Boy, Madame, Father… Nameless they may be—and this, of course, locks in with the history of the closet — but each is no less recognisable for that. For gay people, as for many others, the anonymity of city life may be its main attraction rather than a cause of alienation or loneliness.

Bartlett’s London is a gay London (but not the only gay London), mainly experienced nocturnally. Anonymity and marginality give these gay men a spectral presence behind the scenes of the city. London itself, although eventually recognisable in a few of its details, seems to be more a state of mind than a city of brick and stone. As if uncannily conjured up as the setting for an allegorical masque, it is shimmering and insubstantial, a city shaped by a specifically gay act of the imagination. There are no heterosexuals here, except as looming stereotypes of otherness.

As is already suggested by its title, Ready to Catch Him Should He Fall adopts a heightened rhetoric that sensitizes every detail, to the extent that the whole urban environment — topographical, architectural, social — seems to participate in the novel’s central emotional events. Bartlett has derived this technique more, I think, from Dickens than from his great hero, Oscar Wilde. But, for better or worse, his emotional palette is more limited than Dickens’. Even mundane events are raised — if that is the right word — to operatic levels of intensity from which the narrative never rests. Everything is extraordinary, everything beautiful, everything tragic. This is a rich diet — too rich for some — but not gratuitously so. It suits the book’s strong sense of a life made meaningful by the ceremonials of everyday life. For me, it also carries more recent echoes of Maureen Duffy’s remarkable novel The Microcosm (1966), mainly set in a lesbian bar in London, with parallel narrative strands that put gender-bending into a context going back to the eighteenth century.

Like its main characters, Ready to Catch Him’s main location is given a generic name, The Bar. This establishment, run by Madame (perhaps based on Mme Lysiane in Jean Genet’s novel Querelle de Brest), sits in its street anonymously, with no sign at its door, no lights, not even a street number. For special occasions it is sometimes temporarily renamed — The Lily Pond, The Jewel Box, The Gigolo, The Hustler, The Tea Room, The Oasis, The Hole, Grave Charges, The You Know You Like It — but its door is never marked and, by the time of narration, it has either closed or moved elsewhere. Although it has a regular clientele, deeply involved in each other’s nocturnal lives and unfailingly loyal to Madame, whom they all treat as a ruling matriarch (and who subsequently asks to be called Mother), The Bar’s permanence is ephemeral. There is a shared understanding that, by some obscure rule of collective consciousness governing such places, any gay bar may close down without notice, or a trend or rumour may suddenly lose it its clientele as they move on to some other establishment. Like Duffy’s lesbian bar, it hosts a microcosm of gay life.

There are times when The Bar is dressed up, for a special occasion, as ‘Amsterdam or Paris or something like somebody’s idea of America for the evening’, or at other times as a past era in the life of ‘our own dear city’. Not until more than half-way through the book do we start to get named locations that finally identify this as London. A storm takes place. (This is, apparently, the notorious night of 15th-16th October 1987, when, after the BBC weather forecaster Michael Fish reassured his viewers that there was not going to be ‘a hurricane’ overnight, a massive storm did devastate the south of England.) The novel’s account of this night brings out a sudden flurry of names: the Strand, Trafalgar Square, Ludgate, Aldwych, Park Lane … In particular, various monuments and statues are invoked, and the city itself is named at last: ‘on churches, tombstones, banks and derelict theatres, all the angels of London wept’. In a subsequent account of people and objects injured in the storm, the Charing Cross Road and the National Gallery are named. But then we lose sight of the West End again and go back to the real city in which people actually live.

The hostility of the city, which Bartlett is constantly emphasising, is somewhat neutralised by the effects of sub-cultural solidarity. The Bar provides not only a refuge from the outside world but a small social world in its own right, as well as an extended family for those who have left their biological families behind in the provinces and those whose families have rejected them. This is what had come to be known as the ‘gay community’, built not so much on a shared minority sexual interest as on the social politics of marginality. What The Bar’s clientele have in common is their shared oppression. Although the novel’s events take place at the height of the AIDS epidemic, Bartlett hardly dwells on that at all. It is enough to know that Mother keeps a stock of free condoms on the bar.

The novel outlines the development of a love affair between an older and a younger man, O and Boy, a story foretold and hoped for by the gossips in The Bar before its two protagonists are even aware of each other’s existence. When they do come together, the aptness of their existence as a couple is viewed by the others with a sense of fated inevitability. Mother formally announces their engagement and gives them financial help in setting up their first home together. In due course, she performs the rites of their marriage. For a while, they live as a nuclear family, looking after the child-like Father, who may or may not be Boy’s actual father, until his death.

Much of this narrative takes place indoors, in either The Bar or one of a couple of council flats. At the beginning of the novel, Boy lives in a flat ‘on the twentieth floor of a council block right close by the river on the east side of the city’. By day, he has a wonderful view of ‘the great and glittering river’, and by night ‘the great towers of the financial district to the west’. With a guide book open in front of him, he identifies the various landmarks he has visited on foot (he is living a hand-to-mouth existence on Social Security) and he has learned the names of ‘all the streets where the distant, anonymous towers of the banks and finance companies’ stand. These are unspecified references to the Square Mile, that great rats’-nest of state-sponsored embezzlers, rather than to the later One Canada Square (Canary Wharf), which was still being erected at the time the novel was being written. Not until his third novel, Skin Lane (2007), would Bartlett look at the Square Mile in full, realist detail, conjuring up an atmosphere both spooky and sinister.

Despite the virtual fog of its deliberate vagueness about urban detail, Bartlett’s novel subscribes to a theme that is also crucial to much of his other work, both literary and theatrical (he is better known as a director and performer than as a novelist), that gayness as we live it today has a cultural history that links us closely with our sub-cultural past. Bartlett has a particular interest in the late nineteenth century, but when he was writing Ready to Catch Him others had been researching London’s ‘gay’ past with very revealing effects. In his pioneering work on London’s eighteenth-century ‘molly houses’, Rictor Norton had reported that ‘there were actually more gay clubs and pubs in the heart of London in the early 1720s than there were in the 1950s’.

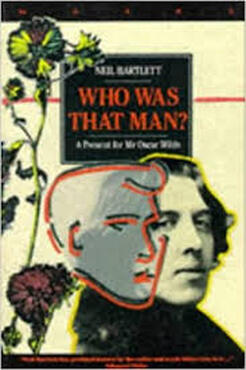

Bartlett begins his wonderful book on Oscar Wilde, Who Was That Man? (his first book, 1988), with a monologue by a modern gay Londoner, himself. He speaks of having moved to the city in his early twenties (‘I don’t think anybody’s life changes as fast as a gay man’s when he moves to a big city’) and of a tendency to connect his own life there with those of previous generations of man-loving men:

Bartlett begins his wonderful book on Oscar Wilde, Who Was That Man? (his first book, 1988), with a monologue by a modern gay Londoner, himself. He speaks of having moved to the city in his early twenties (‘I don’t think anybody’s life changes as fast as a gay man’s when he moves to a big city’) and of a tendency to connect his own life there with those of previous generations of man-loving men:

I’d be walking up the Strand, dressed to kill, and then I’d find myself looking up from the street to all the nineteenth-century façades above me, and fantasize that all the buildings of the West End had seen other men before me living a life after dark, that somehow the streets had a memory. What if I rounded the corner of Villiers Street at midnight, and suddenly found myself walking by gaslight, and the man looking over his shoulder at me as he passed had the same moustache, but different clothes, the well-cut black and white evening dress of the summer of 1891—would we recognise each other? Would I smile at him too, knowing that we were going to the same place, looking for the same thing? (Italics as in original.)

I assume Bartlett’s midnight walk down Villiers Street towards the Embankment is going to lead him not all the way down to the river but to Heaven, the famous gay nightclub under the railway arches behind Charing Cross Station. That he should imagine a man of Oscar Wilde’s time ‘going to the same place’ is characteristic of Bartlett’s disregard for literal accuracy when making a large number of radically revealing comparisons between the two periods. Regardless of their differences, Bartlett’s London is Wilde’s London.

In Wilde’s only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), Dorian has to step outside the glamour of his life as a wealthy, upper-class aesthete to indulge in his most unrespectable vices. Although he takes some of his wealth and all of his personal glamour with him when he crosses the city from West to East, it is among the outlaws and immigrants of the docklands that he purchases his nocturnal pleasures, both sexual and narcotic. In the classless brothels and opium dens of the East End, his beautiful body pays him its meagre dividends while his portrait ages and decays up in the attic of his exquisite house in the West. Aesthetes though they are, and unemployed, the characters in Ready to Catch Him are not the idle rich of Wilde’s novel. Yet their lives are no less cultured, elegant and glamorous than those of Lord Henry Wotton, Basil Hallward and Dorian Gray. In Bartlett’s fiction, as in his theatrical work, glamour is not the fixed essence so many people make it out to be. It is a construction, a performance, a state of mind. All it requires is not money but imagination—and, of course, a dressing-up box. And glamour knows no gender.

Concentrating on the nocturnal sub-culture and on the kind of men who identify themselves as belonging to it, Bartlett’s novel notably ignores various key urban locations that feature in other important gay novels. Prominent among these are public lavatories, where men-who-have-sex-with-other-men (as opposed to men who identify as gay) are wont to access the sheer convenience of sex-without-conversation with men-without-sexual-identity. These are spaces of the deepest ambiguity, dedicated to the lowliest of physical functions yet conducive to thoughtfulness; places of enrapturement and entrapment; coldly functional yet romantic; designed for solitary shame yet apt to enable the most unexpected connections; boring and exciting, disgusting and delightful … (I could go on doing this indefinitely.) For some, they are places of regrettable necessity; for others, as exotic as any palace of Harun al-Raschid’s, promising all manner of sensual pleasures. Angus Wilson took a radically different approach when he located the central moral event of his first novel, Hemlock and After (1953), at the entrance to the gents’ public lavatories in Leicester Square. It is here that the conscience of the book’s central character, Bernard Sands, is tested and found wanting. An exemplar of and standard bearer for liberal humanism, Bernard, himself homosexual, witnesses the arrest of another man for importuning. In contrast with another witness, Bernard feels no impulse to try and save this youth. Instead, seeing the terror in the arrested man’s eyes, he feels a surge of ‘violent excitement’. This, as Wilson’s unrestrained narrator puts it, leaves Bernard Sands on the side of ‘the wielders of the knout and the rubber truncheon’.

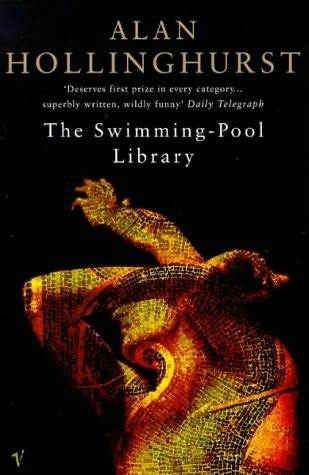

The London of Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming-Pool Library (1988) is divided into distinct sectors of activity, interconnected by the tube network, travelling on which the novel’s narrator and central character Will Beckwith experiences as having a consistent erotic charge. Blessed with as many excuses for complacency as Dorian Gray — beautiful, clever, rich, privileged — Will smugly shuttles between his flat in Holland Park and a gentleman’s club on Great Russell Street in Bloomsbury, the swimming pool and changing rooms of the latter being his principal source of young men to have sex with; but he is shocked out of his self-indulgent routines by two key events, one in a public lavatory in Kensington Gardens, the other in a generic council estate of tower blocks in the East End. In the former, he rescues a peer of the realm, Lord Nantwich, by giving him the kiss of life when the old man suffers a heart attack; and in the waste land of the latter he is queer-bashed by a bunch of skinheads.

The London of Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming-Pool Library (1988) is divided into distinct sectors of activity, interconnected by the tube network, travelling on which the novel’s narrator and central character Will Beckwith experiences as having a consistent erotic charge. Blessed with as many excuses for complacency as Dorian Gray — beautiful, clever, rich, privileged — Will smugly shuttles between his flat in Holland Park and a gentleman’s club on Great Russell Street in Bloomsbury, the swimming pool and changing rooms of the latter being his principal source of young men to have sex with; but he is shocked out of his self-indulgent routines by two key events, one in a public lavatory in Kensington Gardens, the other in a generic council estate of tower blocks in the East End. In the former, he rescues a peer of the realm, Lord Nantwich, by giving him the kiss of life when the old man suffers a heart attack; and in the waste land of the latter he is queer-bashed by a bunch of skinheads.

For all its social attractions, the whole of Bartlett’s London is a potentially dangerous place for gay men. Throughout the narrative, they are being subjected to homophobic attacks. There are at least six knife attacks, one arson attack on a gay couple’s home, one attack by fists alone, one hard smack intensified by spittle and laughter, metal bars applied to the legs, and innumerable verbal assaults. (In some respects, the portrayal of this gay London under constant threat of random but predictable attack reminds me of Sarah Waters’ portrayal of the Blitz-torn city in her 2006 novel about lesbian lives in 1940s London, The Night Watch.) Finally, inevitably, in a year when two gay men have already been killed, O and Boy are themselves attacked while making their way on foot towards The Bar, O walking in a protective attitude to Boy, ‘ready to catch him should he fall’. Five men surround them and start to ridicule them; but when one reaches out as if to touch Boy’s hair, O scares them off by shouting at them, giving a good impression of not being afraid. Although not physically injured, it is clear that O and Boy are hurt nonetheless. The trauma arises from the mere threat of violence in a context of frequent attacks on others. Context is all.

Ready to Catch Him emerged from a repellent period in British social history, when the vindictive instincts of Tory back-benchers and tabloid journalists had combined forces with the contingent tragedy of the AIDS epidemic to try to reverse the limited gains gay men and lesbians had achieved in the 1970s. Much of the society seemed unreconciled even to the Sexual Offences Act 1967, which had partially decriminalised male homosexual acts in England and Wales, let alone to the more visible freedoms demanded by gay liberationists in the subsequent decades. As Bartlett’s narrator says, ‘you have to remember how strange the times were. Dangerous, looking back … You have to remember that we lived in a city in which, according to the latest figures’ (whereupon he cites what appears to be a genuine survey from then), 63% of Londoners ‘did not think that people like us should exist’, 72% ‘did not think that we should be allowed to express affection in public’, 82% ‘did not think that the names of men like us […] should be read out at school assemblies’, and so forth. He adds, ‘You, of course, living in a rather different time or in different countries, will find all this hard to credit now’.

Bartlett portrays this as a city waiting to be handed back to its people. Those who have misappropriated it are not named, but at the time the novel was published Margaret Thatcher was still in power after more than a decade, and Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 was inhibiting public discussion of homosexuality despite a desperate need for such discussion in the face of the AIDS epidemic and the hostility it had aroused. Section 28 stipulated that a local authority might not ‘intentionally promote homosexuality’ or ‘promote the teaching in any maintained school the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship’. Hence the topicality of Bartlett’s representations of constructed and performed family rituals. Although not blood relatives, the characters in his book nominate each other as family members and, even without literally delving into the dressing-up box, do a better job of looking after each other’s interests than the ‘real’ families they came from.

In the closing pages of the book, Bartlett imagines a future night of celebration and liberation: ‘I wish that Boy could look out from their fifth floor balcony and see something like that’. He thinks of other cities: ‘let it be the night Franco died … let it be Riga, let it be Budapest, let it be Berlin … let it be the night they changed the law and we danced all night’. The gay men of 1990 were still waiting for their 1989. Until then, their London would remain a twilight world, always out of focus and always out of sync. Reading this book now, we do indeed live in ‘a rather different time’. The gay male age of consent was reduced in 1994 and equalised with the straight one in 2001; Section 28 was repealed in 2003; and the offences of ‘buggery’ and ‘gross indecency’ (of which Oscar Wilde had been convicted in 1895) were abolished at last in 2004.

Gregory Woods is Emeritus Professor of Gay & Lesbian Studies at Nottingham Trent University, UK. He is the author of Homintern: How Gay Culture Liberated the Modern World (Yale University Press, 2016). His poetry is published by Carcanet Press.

The Bar

The last place in which you could find a bar like The Bar is Old Compton Street in Soho, the main drag of central London’s ‘gay village’. Although it has a long history as a place of resort for sexual dissidents, and therefore as a neighbourhood to be reviled by resentful homophobes (the gay pub the Admiral Duncan was nail-bombed by one such on 30th April 1999), Old Compton Street has become a kind of showplace for liberal tolerance, much frequented by sightseers and visitors to the city, both provincial and foreign. It is to the ordinary gay population of London as Oxford Street is to ordinary shoppers in Streatham or Hackney.

Of these clubs and pubs, some would be known for a leather crowd, others for drag, others for rent boys; and as fashions come and go, so would different crowds, drugs and music. Men would be led to them by hearsay, but also by the London guide pages of newspapers like Gay News (1972-1983) and the freebie Capital Gay (1981-1995). Some of the above and many comparable places still exist, dotted around London’s towns and villages, still varied in style, still apt to change at short notice, and still subject to the whims of collective taste. They are now more likely to have a mixed clientele (gay and straight) than in the 1980s; and, instead of searching for them in the gay press, one finds them now via online guides and general social networks like Facebook or specifically gay ones like Grindr. Bars as protective and enclosed as The Bar have, I think, vanished into history.

Neil Bartlett, Skin Lane, Serpent’s Tail, 2007

Neil Bartlett, Who Was That Man? A Present for Mr Oscar Wilde, Penguin, 1993

Maureen Duffy, The Microcosm, Virago, 1989

Alan Hollinghurst, The Swimming-Pool Library, Vintage, 1998

Matt Houlbrook, Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957 , University of Chicago Press, 2005

Rictor Norton, Mother Clap’s Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England, 1700-1830, GMP, 1992

Sarah Waters, The Night Watch, Virago, 2006

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, OUP, 2006

Angus Wilson, Hemlock and After, Faber, 2008

Gregory Woods, ‘Queer London in Literature’, Changing English, December 2007