Ken Worpole

This article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

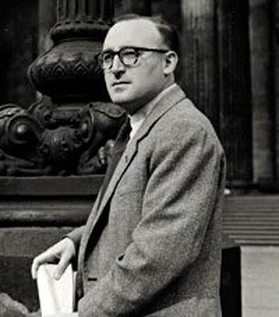

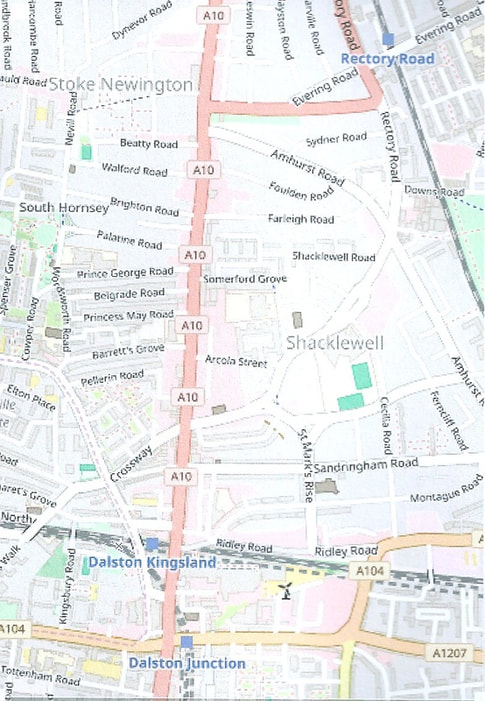

Alexander Baron was born in 1917 to Jewish parents who had separately grown up in Bethnal Green and Spitalfields prior to marriage and setting up home in Hackney. The new family started with one room in Abersham Road, then two rooms in Sandringham Road, before settling in a small terraced house in Foulden Road, Stoke Newington, the setting for what became one of his most accomplished novels, The Lowlife. His father, Barnet Bernstein, was a fur cutter, a ‘very prim and correct chap’, and his mother a former factory worker in the docks.

The young Joseph Alec Bernstein, as he was then called, attended Shacklewell Lane Primary School, which was then considered ‘rough’, though he later described his years there as ‘the happiest time of my life.’ At the age of eleven he won a Junior County Scholarship to attend Hackney Downs Grammar School (also known as The Grocers’ Company’s School), subsequently made famous as the place where the young Harold Pinter was first encouraged to write. In 1954 Pinter adopted the stage name of David Baron, the surname possibly adopted from that of his by now already famous namesake – who had anglicised his name from Bernstein to Baron soon after the war. Baron’s first novel, From the City, From the Plough, a fictionalised account of the D-Day landings, published in 1948, went on to sell over a quarter-of- a-million copies and made him famous: a fame with which he was never comfortable and went out of his way to avoid.

Prior to the war Baron had been politically active on the left, frequently in clandestine ways given the political temperature of the times. In 1983 I interviewed him for a book I was writing, Dockers and Detectives, which addressed several themes which then pre-occupied me: the literature of the East End, and the popular literature of Second World War. Baron’s fiction covered both. The interview was memorable because of the modesty and honesty with which Baron talked about his life, his politics, and his literary career. It is wonderful that a number of his best novels have now been re-issued.

Prior to the war Baron had been politically active on the left, frequently in clandestine ways given the political temperature of the times. In 1983 I interviewed him for a book I was writing, Dockers and Detectives, which addressed several themes which then pre-occupied me: the literature of the East End, and the popular literature of Second World War. Baron’s fiction covered both. The interview was memorable because of the modesty and honesty with which Baron talked about his life, his politics, and his literary career. It is wonderful that a number of his best novels have now been re-issued.

The more I read the novels, the more heartfelt and anguished I realise them to be, whether writing of the horrors of war, of anti-semitism, or of the collapse of the political ideals which led a generation, including a disproportionate number of British Jews, to attach themselves to the communist cause. Nevertheless, there was most certainly happiness in his early life, and a genuine love of the streets in which he grew up and played, and the book which best conveys Baron’s affection for this part of Stoke Newington and its wider Hackney environs is undoubtedly The Lowlife.

First published in 1963 it is a mordantly picaresque novel of contemporary local life and colour, yet a carefully interwoven back-story hints at Baron’s need to address the fate of the Jews in the Holocaust, only then being fully realised for the enormity it was. Critic Susie Thomas is surely right – acknowledging and following in the wake of the work of Holocaust historians – that post-war euphoria and national reconstruction programmes in Europe had, for several decades after the war, prevented a full realisation of the nature of the ‘Final Solution’ planned and enacted by Hitler.

It wasn’t until the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961 that the true horror of what had been a vast programme of racial genocide dawned on the world. Until the early 1960s, there had been a considerable degree of historical repression, or inability to find a way of describing, let alone analysing, what even then seemed unimaginable. The Lowlife comes at this subject tentatively, but with great – and disturbing – effect. Initially regarded as a comic novel, full of wide-boy schtick, today its bleaker themes now seem the more enduring.

When I interviewed Baron I had asked him how his own Jewish background had influenced his fiction. Initially, he said, he had declined the opportunity to put the Jewish experience, either of London’s East End or of the war, in his writings. There were two reasons for this. Firstly, he ‘always had a personal rebellion against the idea of a separate Jewish identity. My father and both my grandfathers were freethinkers and so am I. I’m an atheist. I never wanted to live within this defensive world called the Jewish community.’ Secondly, he saw his respectable, free-thinking Hackney childhood as being geographically and culturally well beyond the classic Jewish East End, even though both parents had once belonged there. After the first two volumes of what we might now regard as his war trilogy – From the City, From the Plough (1948), There’s No Home (1950) and The Human Kind (1953) – he began to change his mind on this. ‘I had to write a Jewish novel,’ he told me. ‘I had to get something off my chest.’ With Hope, Farewell (1952) is replete with Jewish themes and anxieties, though in The Lowlife these pre-occupations are integrated into a more fully realised and exemplary piece of fiction.

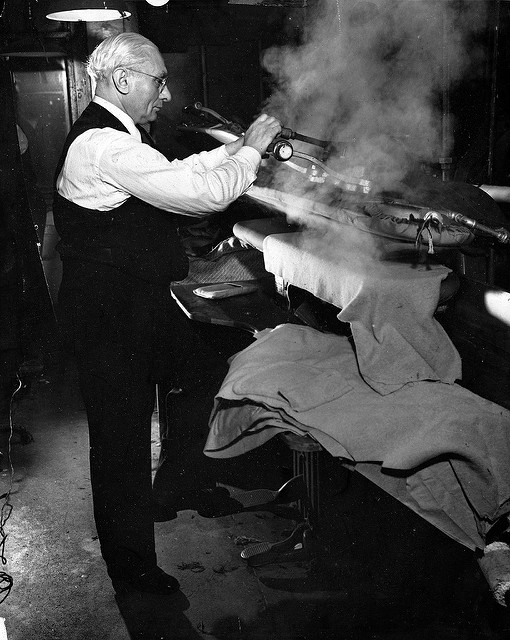

At the novel’s heart is its narrator, Harryboy Boas, a sometime Hoffman presser, gambler, reader of 19th century French novels, and one of a dying breed of luftmenschen, the elderly Jewish gamblers and street philosophers, who once filled the pavements of Whitechapel, Mare Street and Stoke Newington of a summer’s evening to put the world to rights, exchange news of casual work in the rag trade, and discuss the form of the evening’s dog-racing at Harringay, Clapton or Walthamstow. We might be encouraged to believe that these men led charmed lives, without responsibility, but Harryboy’s story cuts to the bone: he is an economic refusenik but not a moral one.

While the novel opens in celebratory style, as an evocation of a childhood home and street life that he adored, it soon reaches into the darker corners of human experience and history. It may well be that Baron, like many intuitive writers, did not know where this novel was going to take him when he started. ‘It’s actually set in Foulden Road, Stoke Newington – Foulden Road in its heyday,’ he told me. As a child he had grown up and lived with his parents at No 6, though in the novel the street is re-named Ingram’s Terrace, and is initially evoked as a multi-racial arcadia. It was in Foulden Road that Baron learned to tell stories. ‘In the street when I was a small kid, I used to tell stories. I wasn’t very good in a punch-up. Story-telling gave me status. I could sit down on the kerb, with the others all around me, and tell them a story.’

After the war, when the demobbed would-be writer returned to live at his parents’ home in Foulden Road, the street was beginning to change. ‘The black people who came were so gorgeous and respectable,’ he recounted. ‘The sight of them all going up to the Baptist chapel on a Sunday morning, the wives wearing these big Ascot hats and the dads polished, the boys in Eton suits, was marvellous. I’ve always had a great love for Foulden Road. I’ve sometimes said to my wife, “If I ever became a really successful writer, I’d buy that house in Foulden Road”, my mum and dad’s house. I would have made it my working place, to go to every morning – instead of working at home. Or I would have arranged for some nurses to live in it.’

However, soon the cracks are beginning to show. Into the three-storey house where Harryboy rents a room from his depressed and fearful Jewish landlord, Mr Siskin, arrive new tenants: Mr and Mrs Deaner and their young son Gregory. The Deaners argue all the time over money and parental responsibilities, and the young boy quickly gravitates towards Harryboy’s room where he finds a more sympathetic, avuncular interest. Harryboy’s strength is his generosity towards others. His weakness, apart from reckless gambling, is the desire to present himself to the world as a bon-viveur and wealthy boulevardier. This happy-go-lucky persona quickly results in him lending money to the Deaners – money he doesn’t have. Soon he is in trouble with his sister and her husband – as well as a group of gangsters – as he hits the racetracks and the card games, borrowing money and losing it in a series of dramatic scenes. With nowhere left to run to, he has to fight his way out of an encounter with a Buick-load of ‘heavies’ sent to punish him for failing to pay his debts. The novel concludes with what remained of his family loyalties in tatters, while his one great moral gesture – the decision to donate an eye to save the sight of the Deaners’ son badly impaired in a firework accident – is no longer required.

It is this complex overlay of story lines – humorous and tragic – which works to give the novel a lasting resonance, and it is today the work which for Baron is best known. It has been enthusiastically adopted by aficionados of the London novel as one of most successful evocations of the post-war city in a period of rapid cultural change, as one group of immigrants is displaced by another. In fictional terms it could be regarded as an update of the well-established tenement or lodging house novel, of which Richard Whiteing’s No 5 John Street (1899), Norman Collins’ London Belongs to Me (1945), Patrick Hamilton’s The Slaves of Solitude (1947) and Lynne Reid Banks’ The L-Shaped Room (1960) are amongst the most well-known and influential examples. The rooming house conveniently provides the novelist with a ready-made set of characters, each with their story to tell, and has been one of the staple genres of the London novel.

Yet though The Lowlife initially adopts this formula – and Baron always saw the novel as an exploration of social morality, best imagined and elaborated in the more confined settings of the conscript army, the political party, the lodging house or the street – it soon develops a quite distinctive plot-line of its own. This is principally achieved by having the story narrated in Harryboy’s world-weary, laconic voice, enlivened as it often is by Yiddisher borrowings. Here men are schnorrers, schmocks, meshuggahs or decent mensch. Tone of voice is vital to Baron, and he was particularly struck by the similarities between Yiddish and East End styles of speech and inflection. ‘I don’t know if you’ve noticed it in East End life,’ he told me, ‘the humour, the ironic expression which is as much East End as it is Jewish. To me… there was a symbiosis between young Jews and the young Anglo-Saxons. You couldn’t tell one from the other. They spoke the same language. East End boys, if they had dark hair, you couldn’t tell from Yiddishers. Cultures mingle. These characters radiate the will to live.’ He later said that when he joined the army he was surprised – pleasantly – to find that a lot of gentile East End recruits knew more Yiddish words than he did, which they had picked up in the street market or at the dog track.

Other story lines weave through the novel, reinforcing the overall mood of disillusionment (compared with the post-war optimism of Rosie Hogarth, for example, published in 1951, though not evident in With Hope, Farewell). We are provided with a harrowing portrait of Harryboy as a gambler and as a self-destroyer: a person who ultimately eschews all human relationships in preference to the adrenalin of chance and fortune. ‘The gambler is the one who goes with no peace, no release, till he has annihilated himself,’ Harryboy says to himself, at the end of yet another evening of losing everything. It is ‘something like death’. Baron had often come across such men, as he told me: ‘I’ve known that gambling streak in the Jews. I have come across, in the army among other places, some of these chaps. One or two of the old school Jewish gangsters as well.’ Gambling of course represents a classic form of existential despair – life is absurd, arbitrary, and meaningless, so why not live for the moment and forget tomorrow. After all, tomorrow never comes. He is also haunted by the miserable deaths of both of his parents: his mother in a flying bomb conflagration which reduced the street to a ‘crater full of garbage’, and his father of gangrene in the London Hospital, alone.

The arrival of the Deaners and the attentive devotion of young Gregory, also stirs memories within Harryboy of an affair he had once had in Paris, with a young Jewish restaurant cashier, Nicole, ending with the outbreak of war and his return to join the army in England. Some months later he received a note telling him she was pregnant. Soon after, we are led to assume that she and the child disappeared into the death camps. Even the sight of young children is enough to evoke in Harryboy’s mind the most desperate of thoughts.

The arrival of the Deaners and the attentive devotion of young Gregory, also stirs memories within Harryboy of an affair he had once had in Paris, with a young Jewish restaurant cashier, Nicole, ending with the outbreak of war and his return to join the army in England. Some months later he received a note telling him she was pregnant. Soon after, we are led to assume that she and the child disappeared into the death camps. Even the sight of young children is enough to evoke in Harryboy’s mind the most desperate of thoughts.

I only have to see a nursery school teacher leading her procession of toddlers to the park, and at once I imagine a procession of little innocents, endless, endless, being herded with every possibly cruelty to their deaths. If I walk into the Deaners’ living-room and see a pair of Gregory’s shoes in the corner, I think of the mountain of children’s shoes, the shoes of dead children, found in one of the camps, sixty feet high.

Harryboy’s never-to-be-seen child could have been, almost certainly was, one of those children. We are, by now, a long way from the playful multi-racial street portrayed in the novel’s opening scenes.

Another key mise-en-scène in the novel is the expensive and ornately furnished home of Harryboy’s sister, Debbie, and her bookmaker husband, Gus, in Finchley, where from time to time Harryboy is invited to eat (with an obligatory lecture on his need to reform his life and settle down), or to which he is compelled to visit when in desperate financial straits. Initially the reader feels that Debbie and Gus have been set up to satirise those Jews who have left behind the slums and terraced streets of Stepney and Hackney to acquire respectability in the northern suburbs. But in the course of the novel we come to appreciate that they really do care for Harryboy, even though time and time again he betrays their trust (while relieving them of considerable amounts of stake money to be gambled away).

Debbie is convincing and the exchanges between her and Harryboy contain all the pain and anxiety of troubled sibling relationships. She was once the protective older sister ‘who ran with a gang of rough boys and protected me’, which she still does, though with ever-decreasing success. The other women in the novel are less sympathetic, notably Evelyn Deaner, the nagging, ambitious and explicitly racist wife of Vic, and Marcia, a Soho call girl whom Harryboy frequents when he has the money. The money-scraping lives of Vic and Evelyn ring true. Vic earns a pittance as a trainee accountant who spends his evening studying for his exams, while Evelyn cannot wait to move to a more respectable area. Meanwhile, sharing a house with a black family is for her the ultimate humiliation. The exchanges between the couple, with endless arguments over money, childcare responsibilities, and other domestic matters, possesses genuine dramatic tension. Yet when portrayed on her own, Evelyn’s character is mostly unflattering, though Baron does provide a personal background to her demeaning sense of lost opportunities – a recurrent Baron theme – and when her son Gregory is badly injured, she rises to the occasion.

Marcia is even more of a problem. A wealthy married woman who seeks financial independence from her devoted husband, she operates as a high class prostitute with her own maid in a central London apartment, building up a financial empire through property speculation (including the use of hired thugs to harass tenants), while happily accompanying Harryboy to smart Brighton hotels and restaurants, ostensibly out of the goodness of her heart. There is a scene between Marcia and her husband when the latter arrives in a restaurant – where Harryboy is entertaining Marcia to a splendid meal – to plead with her to return to him. It is ferocious in its portrayal of public sexual humiliation. Sexual desire and its frustration is a continuing undercurrent in the novels of this period, and on such matters Baron was forthright and ahead of his time. In the various clothing factories where Harryboy works when needing the money, casual sexual encounters are an everyday affair, sometimes degrading, sometimes satisfyingly pleasurable, as they are in other Baron novels, including, unsurprisingly, the war trilogy.

Unusually for a classic ‘London novel’ there are no pub scenes. In the period of which Baron was writing, even bohemian or quasi-criminal Jewish life found its social milieu in the gambling joint, the dog track, the restaurant, the dance-hall or the night club rather than the public house. Food was especially important as a form of luxury and conviviality. Debbie’s meals for Harryboy are fully described, as are Harryboy’s expensive restaurant meals with Marcia. A common love of food as a metaphor for a love of life is made explicit when Harryboy shares a chicken cooked and served by his black fellow tenants, Milly and Joe. They ask him why Evelyn dislikes them so much, and he replies that it is because ‘We got too much life. We are not liked because we have too much life in us…the way we eat, that way we live. You and me, Joe, we mop the plate dry. We suck the last gob of marrow. We lick our fingers. From our fathers and grandfathers we know hunger, and we value food. In our blood we know an axe can fall on us at any second. So we live. We live.’ Yet those who take life as it comes are in a minority, for when Joe further asks how he and Milly can become accepted by the other residents, Harryboy simply replies, ‘You’re living in the house of the dead. I don’t know what to advise you.’

This contrast between the sensual delight in food shared by Jews and black people and the miserable evening meals eaten by the Deaners evokes the place of ritual in family life which recurs in Baron’s fiction, even though he had largely disavowed his Jewish beliefs. Living for the day, not heedlessly or irresponsibly, but because the future is uncertain, is a one of the underlying reasons for domestic ritual and the enjoyment of the pleasures of food, family, companionship and sexual fulfilment. However, because of his gambling mania, Harryboy carries this living for the moment to a dangerous and ultimately self-destructive degree. He is a man with a past, a present, but no future. What makes his predicament even more intolerable is that very much like a character in a Kafka story, he carries a burden of continuous guilt: ‘So the inside of my head, not for the first time, turned into a courtroom.’

With the advantage of hindsight, we can now appreciate The Lowlife, not just as a piece of urban comedy, which it is, but also as a season in hell, leavened by Harryboy’s gallows humour and self-deprecating wit. He is one of London fiction’s most memorable characters, and we can only wish him well.

Foulden Road today

Foulden Road today is much as it was when Alexander Baron lived there from the 1920s onwards, though many of the houses have been returned to single family homes after decades of multi-occupation.

The Foulden Arms at the eastern end of the road closed in the early 1980s and was converted into flats, like many street-corner pubs in this part of London. The road was lucky to survive several nights of bombing during the Blitz, which badly affected Stoke Newington. On 13th October 1940, a parachute-mine landed on the tenement buildings in Coronation Avenue, no more than one-hundred-and-fifty yards from Foulden Road, killing over a hundred people, many of them Jewish, in one of the worst civilian incidents of the war, and this terrible event is alluded to in Baron’s novel, With Hope, Farewell. In The Lowlife, Harryboy’s mother is obliterated in a similar disaster.

The Foulden Arms at the eastern end of the road closed in the early 1980s and was converted into flats, like many street-corner pubs in this part of London. The road was lucky to survive several nights of bombing during the Blitz, which badly affected Stoke Newington. On 13th October 1940, a parachute-mine landed on the tenement buildings in Coronation Avenue, no more than one-hundred-and-fifty yards from Foulden Road, killing over a hundred people, many of them Jewish, in one of the worst civilian incidents of the war, and this terrible event is alluded to in Baron’s novel, With Hope, Farewell. In The Lowlife, Harryboy’s mother is obliterated in a similar disaster.

At the ‘top end’ of Foulden Road, where it joins Stoke Newington Road, there were two small mews terraces, formerly stables, which would have been converted into sweat-shops in Baron’s time, and a large drinking trough for horses stood near this junction until the 1970s. Baron’s family lived almost next door to these mews, and home and work were often near to each other in the ‘rag trade’ which flourished in this area. Close by was the monumental Simpson’s clothing factory at 92-100 Stoke Newington Road, built in 1929 and at its busiest employing over 3,000 people producing 11,000 garments per day. Harryboy almost certainly would have done a few shifts there as a Hoffman Presser. The company closed the building in 1981, since when it has functioned as a storage depot, with a Turkish community centre occupying the front part of the building.

The main parade of shops at the top of Foulden Road largely consists of Turkish cafes, restaurants, wedding shops, florists and supermarkets, all serving the Turkish, Anatolian and Kurdish communities resident in this district. Within a hundred yards of No 6 Foulden Road, on Stoke Newington Road, was the Apollo Cinema (now an ornately decorated mosque).

The main parade of shops at the top of Foulden Road largely consists of Turkish cafes, restaurants, wedding shops, florists and supermarkets, all serving the Turkish, Anatolian and Kurdish communities resident in this district. Within a hundred yards of No 6 Foulden Road, on Stoke Newington Road, was the Apollo Cinema (now an ornately decorated mosque).

Opened in 1915 it contained over a thousand seats and was designed in a twin-domed Moorish style. A photograph taken of the cinema in 1928 shows it – very unusually – featuring a Yiddish film, ‘Souls in Exile’, made in 1926 by Maurice Schwartz. This film had a few showings in London and Manchester, and that it was shown in Stoke Newington attests to the large Jewish population in the area at that time.

The Apollo ended its life as The Astra in the early 1980s, specialising in Kung-Fu films. Next door to it is the Stoke Newington Baptist Church, which is where Harryboy would have observed and admired the smartly dressed West Indian population attending service on Sunday. Another hundred yards down Walford Road, by the Baptist Church, you come to the Walford Road Synagogue, still in use, its coloured glazed windows permanently protected by metal grilles, giving it something of a fortified appearance, evidence of the sporadic incidents of anti-semitism which occurred in this area for most of the twentieth-century. Such attacks on Jewish properties feature in the plot lines of many of Baron’s novels, most notably in With Hope, Farewell, which concludes with a mildly hopeful gesture of solidarity, when Mark is joined at his local synagogue by two Cockney trade unionist railway workers who have come to help him defend it against another arson attack.

The Apollo ended its life as The Astra in the early 1980s, specialising in Kung-Fu films. Next door to it is the Stoke Newington Baptist Church, which is where Harryboy would have observed and admired the smartly dressed West Indian population attending service on Sunday. Another hundred yards down Walford Road, by the Baptist Church, you come to the Walford Road Synagogue, still in use, its coloured glazed windows permanently protected by metal grilles, giving it something of a fortified appearance, evidence of the sporadic incidents of anti-semitism which occurred in this area for most of the twentieth-century. Such attacks on Jewish properties feature in the plot lines of many of Baron’s novels, most notably in With Hope, Farewell, which concludes with a mildly hopeful gesture of solidarity, when Mark is joined at his local synagogue by two Cockney trade unionist railway workers who have come to help him defend it against another arson attack.

Ken Worpole is a writer and social historian, whose work includes many books on architecture, landscape and public policy. He is married to photographer Larraine Worpole – they have lived and worked in Hackney since 1969. Ken is Emeritus Professor, Cities Institute, London Metropolitan University, and has served on the UK government’s Urban Green Spaces Task Force, on the Expert Panel of the Heritage Lottery Fund, and as an adviser to the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment. http://www.worpole.net/

Further Reading

Titles by Alexander Baron: all editions given are the most recently published

The Lowlife, with an introduction by Iain Sinclair, Black Spring Press, 2010

King Dido, with an introduction by Ken Worpole, Five Leaves, 2009

Rosie Hogarth, with an introduction by Andrew Whitehead, Five Leaves, 2010

With Hope, Farewell, Five Leaves, 2019

From the City, From the Plough, Imperial War Museum, 2019

The War Baby was published for the first time by Five Leaves in 2019

There’s No Home, with an afterword by John.L.Williams, Sort Of Books, 2011

The Human Kind, with a foreword by Sean Longden, Black Spring Press, 2011

Iain Sinclair, Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire: A Confidential Report, Hamish Hamilton, 2010

Susie Thomas, ‘Alexander Baron’s The Lowlife (1963): Remembering the Holocaust in Hackney’, Literary London Journal online, September 2011

Gil Toffell, ‘Cinema-going from Below: The Jewish film audience in interwar Britain’, in Participations, November 2011

Ken Worpole, Dockers and Detectives, Five Leaves, 2008

More details about the image of the man using a Hoffman steam presser are available here

And here’s a 2019 guide to a ‘walk round Baron’s manor’ of Stoke Newington and Dalston.

All rights to the text remain with the author.