Courttia Newland

This article appears in the book London Fiction, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White – and published by Five Leaves. You can order it direct from the publishers by clicking here.

It is often said that London is a many-faceted jewel, ever changing, no two sides the same. The city explored in Iain Banks’s Dead Air is one of unmistakable debauchery, a world of media moguls and PR women, gangsters and their wives, drug takers and DJs, the seething depiction of night owls and their sins. Banks’s not entirely pleasant journey is a whistle-stop tour around bright lights and inevitable dark spots. It’s a London most would have seen through a bus, car, or black cab window, yet very few would have experienced first-hand.

The city as a manifestation of its inhabitants’ more negative aspects, most importantly Banks’s protagonist, shock jock Ken Nott, often means that London is awarded a bit-player’s role in Bank’s narrative, a fleetingly viewed cast member. There is very little rest or respite for Banks’s people. They are career driven, destined to work and play hard for as long as they are able, which echoes many contemporary Londoners’ view of themselves and the place they live. Characters are busy answering phones, taking meetings, socialising with work mates and friends, are constantly on the move. They largely represent the drones of the media hive, both brighter and higher in the hierarchy than worker bees, knowing distinctly that there is no possibility of ever becoming royalty. It’s difficult to tell if they are satisfied with this existence or whether they yearn for more. Nott seems content to amble through life as a largely self-serving personality, and is certainly not in search of any epiphany when we first meet him, high above London’s streets. Following this lengthy prelude, the only chapter of relative tranquillity, we hopscotch from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, action to reaction, each location providing a fast paced, bird’s eye view of the capital and its hedonistic citizens. In Nott’s own words, the rapid pace of his story resembles:

One of those record-breaking domino-falling displays…. A whole toppling, fanning, branching cascade of tiny events, which happen so fast and so together they become one big event.

From the opening chapter, which takes place at a wedding reception for an Asian friend of Nott’s and his English wife, contemporary multicultural London is placed centre stage. Yet quickly, we see this is the domain of the haves, rather than have-nots. The reception is set on the roof of a New York-style loft apartment in the East End: ‘One big space, full of minimalism, but very expensive and artfully arranged minimalism’. After a conversation with his girlfriend, record label PR, Jo, Nott tells us breakfast was ‘orange juice and a couple of lines of coke each’. A gleaming yellow Porsche is parked below, a far cry from the London of the under-privileged. Banks allows the reader a brief critique of his characters and their environment when Nott decides to supplement his liquid breakfast: ‘I hoisted the apple from the glass and took a bite. It looked shiny and great but tasted of nothing much.’

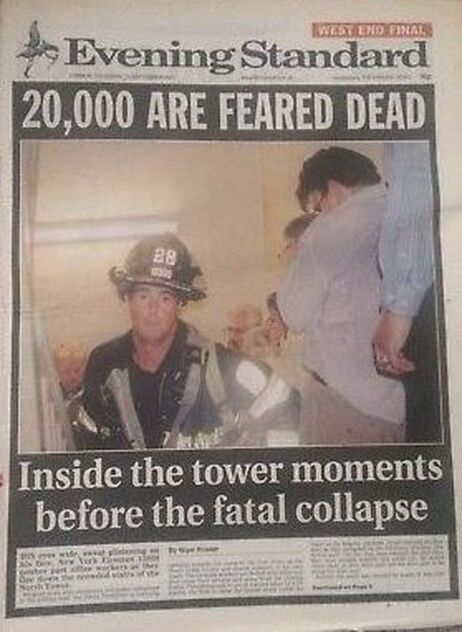

The chapter ends with the admittedly drunken wedding party, led by Ken and his amorous friend Amy, throwing items from the roof; first small fruits, but later old hi-fi systems, radios, bottles and a broken TV. It takes a teenage girl to tell them that throwing away perfectly good food and household items might be wrong, but that doesn’t stop them pitching over a few more bottles of Cava. When the phones begin to ring, the party begins to lose its vigour, and people begin to realise something is wrong. The date is September 11th, 2001. It is a momentous point of change, even if the true repercussions are not immediately apparent.

It’s interesting to note that Banks was once famed for writing novels that explore the ‘80s zeitgeist. Complicity, published in 1993, concerned the city under Thatcherism and was told through the eyes of a morally righteous serial killer. In Dead Air, first published in 2002, the conflicted narrator who lives wrongly while extolling a rigid moral code has returned, and there is an almost morbid attempt to capture London’s frivolity: when the city is still bathed in the notion that the Tories had been kept at bay, if not banished; when commerce flowed and economic downturn was nothing more than a sombre cloud on the horizon. This is an unsympathetic London, full of cruel people who live the high life and cast bold judgement on the world, none more so than Ken Nott, who has no qualms about spouting righteous indignation on his radio show, (via topics ranging from 9/11, religious radicalism, the ridiculous names of pop artists) and then spending the night in a Soho bar, taking copious drugs, and sleeping with many women, including his best friend’s ex-wife. In turning this mostly underground, unseen depiction of London to face the light, a city of excessive spending, drinking, eating, drug-taking and copulating, one has the feeling that Banks may be trying to articulate the nature of the times, and his frustration with those times, as much as a latent frustration with himself (much has been made in reviews of the similarity between Banks and Nott).

What I’m suggesting is not that the author has made an attempt to give voice to London and its environs through verisimilitude – there is very little evocation of place in the novel; areas are name-checked, but not described in any great detail. Scenes take place in these well-known areas, and rapidly move on. Rather, the city becomes a distorted carnival mirror, emotionlessly reflecting the lives of a lead character who lives for the moment, and whose intellectual arguments speak of a man in heated debate with himself, and his own principles.

The first person narrative stays close on Nott’s shoulder, and we remain by his side for the entire novel. This makes a compelling – if claustrophobic – read, especially when he is the subject of so much outside disdain. It sometimes feels as though one is walking a crowded London street at fast pace, constantly shoved by people. The river is traversed back and forth by taxi, Land Rover, bike and white van; but if the vehicles and places are diverse, the mood and people generally remain of a similar type. Nott lives on a houseboat, but it’s moored in Chelsea Wharf. He drinks in a ‘basic Central London pub’, but the Soho clientele are advertising creatives, theatre types, music people, film people, who feel better about themselves because they mix with a smattering of workmen, off-duty drug dealers and the homeless. There are mid-summer river cruises and glittering Limehouse penthouses, raves in disused Beckenham cinemas, drunken camaraderie in elegant three-storey Highgate abodes. Yet through it all, Nott seems dedicated to embedding himself in the underworld of London nights. Even when the novel begins, he is already having a dangerous affair with the wife of a prominent crime boss. One of his two best friends is a club DJ with underworld connections. Nott’s world is one of secret liaisons, meetings with dangerous men to acquire dangerous objects, a high life with inevitable consequences.

It’s this push and pull motion between Nott’s ideas and how he lives that can be taken as an indicator of how Banks himself feels about modern life, exemplified via the city of London. In concentrating his attention on an unsympathetic protagonist, who behaves unspeakably through most of the book, while continually drawing attention to the more negative traits in humankind, Banks immerses us in the mind of someone whose rants, on-air and off, are so all-consuming he rarely questions his own life. There is the blind rush from one locale to the next, the lack of any real friendships, the lack of pride in his chosen career, flagged up at the beginning of the book, in the chapter that follows the food-dropping incident. Nott is casually aware that there is something wrong in his life. There is a weariness of resignation that comes across as flippant, but turns out to be more desperate, more strident, than originally guessed. Read that way, Dead Air presents a cynical, one-sided view of the capital, but a London that exists, in part, all the same.

Midway through the novel, Nott has a rare heart-to-heart with Jo as they stroll along Bond Street. Jo begins by questioning Nott’s work (she is not the only one to do so), and this quickly leads to her summarising his life. She reminds him that he hates most of what he does and what he’s involved in, citing that he doesn’t listen to Capital Live!, and doesn’t like the commercial music he plays, his fellow DJs, or the ads. When she provides a list of Nott’s pet hates, he’s made to realise that in fact, he doesn’t like much of what the world has to offer. When she asks him if there’s anything he does respect he provides a long, mostly insubstantial list, before finally saying: ‘This city’. His reasoning is as random as his constant rants (a shop window of antique fish slices), which Jo easily counters by detailing Nott’s own conflicting views, but again, there is a feeling of nostalgia, an attempt to journey beyond the frivolous. London is turned slowly before the reader’s eyes, bright side to dull, each glimpsed for another, flimsy moment before we move on.

Banks famously said that Dead Air took six weeks to write, and it may be this frenetic energy, the constant feel of movement even though we’re unsure to what end, that fuels the book and gives it a constant ‘nervous’ tinge. Nott, true to his occupation, talks non-stop, babbling about anything and everything to anyone, debating the most mundane but pervasive subjects of modern living – CCTV, Black London slang – to the most compelling. In one particular episode, after a nasty on-air attack on Islam which leads to numerous complaints, Nott is forced by his station manager to conduct a TV interview with a Holocaust denier. Unbeknown to anyone, he concocts a plan to wait until the cameras are rolling, jump out of his chair and punch the interviewee square in the face. Afterwards, when Nott has followed through on his plan and he’s asked why he resorted to violence, he denies the whole thing. The point is somewhat irrelevant, but this basic action speaks volumes about Nott’s moral compass, which tends to swing wildly throughout the novel, a man with the right ideas but the wrong methods, a man most people seem to like despite themselves, even while balanced on the verge of loathing, even when they are offering him their grudging respect.

The cast of friends, co-workers and lovers that orbit Nott seem locked into hapless trajectories. Phil, his long suffering Capitol Live! producer, is dazzled enough by Nott’s rock star lifestyle just to tag along and trade on-air witticisms, but for the most part, steers clear of his rag-tag social life. He tolerates his presenter’s more extreme characteristics with the weary air of a man who has seen his type before, and is comfortable in his role as the ever-faithful sidekick. Jo, Nott’s PR girlfriend, flits in and out of his life and barely seems to register most of the time, even though he’s momentarily devastated when she eventually leaves him for one of her more debauched rock star clients. Her character serves to characterise the fickle nature of London’s media tribe; fashionable, ambitious, sexy and independent, a free-spirit. When they break up, a fairly one-sided exchange that takes place in the bowels of the London Aquarium, a ‘bluey-green wash of underwater luminescence’, Jo is embarrassed, yet casual. She expects she wasn’t the only one cheating, which causes Nott to storm off in a rage, even though it’s true. Craig, his only Scottish friend, whom Nott has been close to since adolescence, meets for drink and smoking sessions borne of a tenuously kept tradition, more for the purposes of ritual than solidarity. As things progress, Craig subtly probes Nott’s choice of career, his attitude to women, eventually his loyalty to him and their friendship. Nott’s illicit affair with Craig’s wife is finally revealed when Craig and Emma decide to resume their relationship. His actions and lifestyle is called into question for the first time, by someone who not only views Nott’s behaviour as distasteful, but actually means something to him. His world is rocked. When their friendship ends, Nott is devastated, and the rapid domino culmination of events begins to roar to an ear-splitting conclusion, as Nott responds the only way he knows how, submerged in alcohol and self-pity.

Only club DJ Ed, and Nott’s beautiful mistress Ceel, are equally single-minded in their admiration, despite everything he does to betray their trust, and all they do in return. Ed is a quite obvious attempt at representing the normalcy of contemporary multicultural London, compared to past fictions, where the presence of people of colour is almost taboo. For the most part Banks does a good job at dramatizing the type of conversations that could take place between a Scot and a man of Caribbean heritage, if the artistic licence of complete honesty was in play. There are times when the dialogue grates, but this is more to do with Banks’s unfamiliarity with London language than any race issues. As his closest London friend and in lots of ways Nott’s foil, unlike Craig, Ed’s moral compass shifts in much the same way: he operates by underworld ethics yet abhors the reputation of Celia’s husband, John Merrial; he loves his mother and sister, yet has no qualms sleeping with Jo behind Nott’s back. Interestingly enough, when Nott learns of his indiscretion, Ed is routinely forgiven.

As the most intriguing of Banks’s cast of characters, Celia Merrial, is an almost mythical figure, sexually liberated and spiritually aware. When they first meet, Celia tells a fantastical story of her own death, recounting when she was struck by lightning on her island of heritage, Martinique, while watching a storm on a high cliff. She believes that the world went in two directions from that point onwards – that one half of her lived, and the other was killed, either by the bolt itself, or by plunging down onto the rocks below. On one side, from shoulder to hip, she has markings on her skin, as if a henna tattoo:

“That is from when I half-died,” she said matter-of-factly.

‘What?”

“From the lightning, Kenneth.”

“Lightning?”

“Yes, lightning.”

“Lightning as in thunder and – ?”

“Yes.”

This is an interesting use of character, which perhaps speaks of chance and Banks’s belief in alternate possibilities, both for the characters and the capital. While again, Celia represents in part the diverse peopling of the city, and after a long, continuing battle, how ordinary that has become, she is very much Ed’s polar opposite, both rich and cultured, married to the mob but entirely divorced from its actions, an ex-model who travelled the world and was moneyed long before she met her gangster husband. She offers Nott a fairy-tale ride, leading him first to the lofty climes of the Dorchester and the Connaught; then, at the novel’s end, down into the rotten underbelly of an underground car park when her husband suspects an affair; before finally, in the last moments of the book, providing Nott with the chance of a new life, the possibility of remaking himself anew. But before that, in those grim moments of the underground car park, when Nott has been tied up and punched and has soiled himself in fear, he suddenly believes Celia’s story, and soon afterwards, embraces a major epiphany;

Maybe I deserve what might happen here. I know I’m not a particularly good person; I’ve lied and cheated and it’s no consolation that little of it was illegal… So maybe I’d have no real cause to complain if I’m made to suffer

In the end, Nott’s is reprieved due to luck more than design and Merrial’s suspicion is cast elsewhere, towards an entirely fictional lover. He is released into the world with a renewed sense of himself, and slowly, carefully over time, Nott and Celia begin to enjoy the normal, everyday relationship they have always dreamed of. Although this is an uncharacteristically optimistic tone for Banks, and indeed for the novel, there is a clear attempt at trying to flood his shadowed tale with light, in trying to allow some escape for us, his readers, and for London, the city loved by protagonist and author alike. When, in the penultimate chapter, Nott admits to Celia that he loves her, she is characteristically wise and profound. ‘”Where love is concerned,” she told me, “you must be a behaviourist.”’ This, more than anything, seems to encapsulate Banks’s meditation on London, Londoners and our relation to each other, and in turn the world. It’s an admirable stance, definitely one worth reading; but perhaps more importantly, one worth fighting for.

Courttia Newland‘s novels include The Gospel According to Cane and The Scholar. His website is at https://courttianewland.com/

Tally Ho!

An area of grazing farmland until 1536, when it was claimed as a royal park for the palace of Whitehall by Henry VIII, the name Soho is believed to have come from a hunting cry. It was later used as a rallying call by the Duke of Monmouth at the battle of Sedgemoor, half a century after the name was first used for this region of London. The Crown leased the area to a succession of Earls who planned to develop the land to imitate Bloomsbury, Mayfair and Marylebone. But Soho never became as fashionable, mainly due to the French immigrants who flooded the area for work.

For a while, Soho was known as ‘le petit France.’ By the mid-18th century, the aristocrats of Soho Square and Gerrard Street had moved away. By the mid-19th century, prostitutes, theatres and music halls had moved in, and by the early 20th century, the area was popular among writers, artists and intellectuals. J.K. Rowling’s French great-grandfather worked in the area as a waiter in the period before the pubs of Soho became filled with drunken poets and artists. Soho’s reputation as a place of debauchery and hedonism was cemented in their prose, poetry and song.

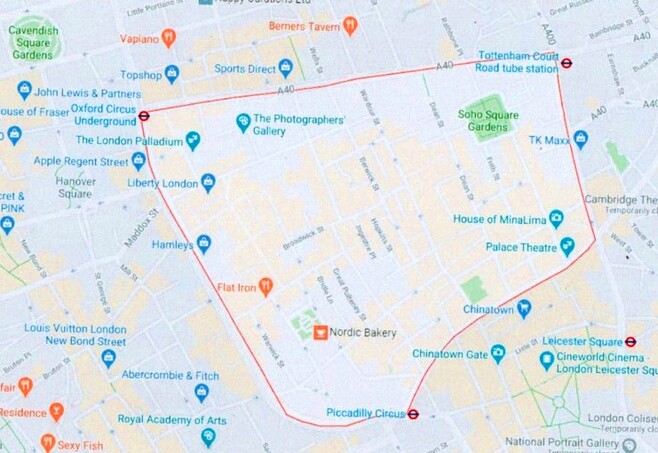

Today, Soho has retained that slightly grubby image, even though the area has changed a great deal. Due mainly to its fame as a place of entertainment, it’s a magnet for the rich and poor, boasting nightclubs, public houses, a few scattered sex shops, late night coffee shops, and chain restaurants side by side with more expensive eateries. There are record shops, London’s main gay village, churches and even a Hare Krishna temple. Gerrard Street is now Chinatown. Soho has become home to the media industry. The British Board of Film Classification has its home in Soho Square – the setting in Dead Air of Nott’s radio station Capital Live! – and the media and post-production community has moved into the area, connecting the heart of London with Pinewood and Shepperton studios. It’s this rich and vibrant industry that Iain Banks has brought to life in his novel, the unseen characters and inner workings of a world we take a passive part in, yet know little of, hear but rarely understand. This one square mile has become a world unto itself, so much so that the neighbouring area, on the opposite side of Oxford Street, is ‘affectionately’ called Noho. There is a deep love for the village and what it represents, past and present, artistic and commercial. Soho epitomises London’s diversity, and continues to fascinate both visitors and residents alike.

References and Further Reading

Iain Banks – Walking on Glass, 1985

Complicity, 1993

All rights to the text remain with the author.