Carla Scura

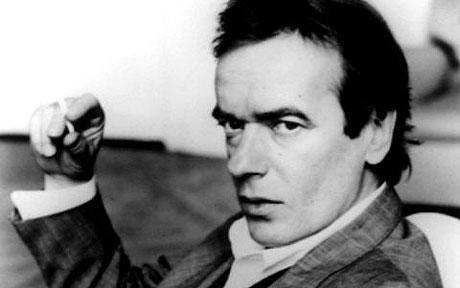

London Fields, often regarded as the strongest of Martin Amis’s novels, is commonly considered as the middle part of his London trilogy, along with Money (1984) and The Information (1995). It’s been an enduring success, and there have been several attempts to adapt the novel for film. It is innovative, a state-of-the-art literary work, which reflects Amis’s clairvoyant vision of London.

Scenario

The year 1989 came at the end of an awful decade for the environment. We witnessed rising ecological awareness along with a succession of environmental disasters. A pervasive fear of the atomic bomb remained palpable with the Cold War still in the background.

At the same time, 1989 became instantly charged with global symbolism. It was the year of the collapse of the Berlin Wall, which paved the way for a new, unexpected world order, so much so that there was talk of the ‘end of history’. The dissolution of the binary opposition (Washington/Moscow) in geopolitics was in some measure reproduced more widely, with a sense of merry catastrophe into the next decade – already seen as particularly crucial because of the numerical, temporal coincidences that beat the time of human existence.

This was the ideal setting for the creation of a novel such as London Fields, published in 1989 and set in 1999, and so embracing those numerical and temporal coincidences. The novel had an unusually lengthy gestation period. Martin Amis began working on it in 1983 and initially had in mind a long short story of perhaps a hundred pages. He saw the work in progress expanding, taking different shapes over six years that were formative for the author, in the personal as well as the professional sphere. So it really is the painful outcome of the 1980s, soaked with then dominant concerns but very much projected onto the future – and onto a symbolical date that lends itself to one of the dimensions of his novel, the apocalyptic.

The Plot in Outline

Samson Young, an unsuccessful American writer, swaps houses with Mark Asprey, a fashionable British writer who lives in Notting Hill. We are in 1999, and Samson Young sets foot in Europe after having been away for ten years. He’s looking for some inspiration for his last novel – he’s seriously ill after radiation exposure – so he manages to make friends with three people he meets by chance in a pub in Portobello Road. He also manages to develop the relations between them, who didn’t know each other well. He parasitizes the complex plot hatched by beautiful Nicola Six against rich Guy Clinch, from whom – by way of her erotic and intellectual appeal – she’s able to steal a huge quantity of money after inventing two characters in distress in Cambodia. To help with her plot the hooligan Keith Talent comes in handy, not least because he can be easily manipulated. All three characters seem to have motive for killing the dark lady, who has always known that she would die on the day of the 35th birthday – November 5th, 1999. Meanwhile, both the weather and the political situation in London are on the verge of catastrophe …

Precedents

There were earlier examples of ‘visionary’ London fictions, of course. Among the more recent precedents, Mother London by Michael Moorcock and The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie were both published in 1988 (it was in 1989 that a fatwa was issued against Rushdie). Moorcock’s novel describes a fantastic London that is turned towards the past, absorbed in listening to the voices of its own ghosts. Nonetheless, with its jabs into four different periods of the twentieth century city – including a London destroyed by German bombs in World War Two – Mother London displays an almost cinematic view of the city, in a manner reminiscent of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Rushdie’s Satanic Verses foreshadows a post-metropolis, since London, centre of the former Empire, ‘Airstrip One, Mahagonny, Alphaville’, is the fulcrum of the magical world of the novel and of History.

The other 1980s visionary account of the city was Alan Moore’s revolutionary graphic novel V for Vendetta. This has recently enjoyed much attention and was made into a very popular film in 2005. Moore set his dystopian London in the 1990s, following a nuclear war in the infamous 1980s. It was published in instalments from 1982 through to … 1989.

The title

So, London 1989. Or rather London Fields, 1999. London Fields is the name of a railway station on the Cambridge line (and which, in one of those bizarre coincidences of life and art, serves the area where another key London writer and visionary, Iain Sinclair, lives). It’s a district of Hackney redolent with history and old-time pleasures: sixteenth century botanists explored it, the diarist Samuel Pepys practiced archery there, and cricket has been played on its fields ever since 1789. Its residents played up this heritage when their neighbourhood was seen in a less-than-positive light thanks to Amis’s novel – though he was not the first to resort to such an evocative, oxymoron-like name: there was a 1983 precedent, a London Fields written by John Milne.

Yet Amis only borrowed the place name. His novel is set entirely in Notting Hill several miles away on the other side of central London, in the districts of W10 and W11. The area is sketched out with topographical precision by the movements of the main characters: Golborne Road’s skyscraper, Portobello Road, Lansdowne Crescent. Setting the novel in Notting Hill not only added to the author’s ‘folklore’ (he lived there for many years), but in a very limited space basically offers a setting that characterizes the city, an extraordinary compression and contiguity of extremes ranging from the luxurious Victorian town houses of Notting Hill proper to the village atmosphere of Portobello Road and the low-cost, down-at-heel buildings near the canal. As far as the plot goes, this allows the otherwise unlikely meeting in a local pub of such disparate characters as The Foil, The Murderee, The Murderer, and the American writer.

‘[T]here are two kinds … two orders of title … The first kind of title decides on a name for something that is already there. The second kind of title is present all along: it lives and breathes, or it tries, on every page’. It becomes evident as you read the novel that Amis went for the latter option, reinforcing this by way of an almost poetic reiteration of the title in the closing words of the introduction: ‘So let’s call it London Fields’. This introductory note contains the coordinates of the novel: London/end of century, each the epitome of the other.

Time, Space, Point of View

After the time coordinates have been provided, we are presented with the space coordinates. London is mentioned in the second page, after New York, thus fuelling the reader’s expectation. ‘Not a whodunit. More a whydoit. I am … a queasy cleric … an accessory before the fact’.

From the beginning, the narrator addresses his own status as writer and artist, the nature of literary fiction, and the product he’s allegedly writing in real time. This speculative aspect is a constant companion to the unfolding events: and as far as the plot is concerned, the final comment in this chapter – ‘If London is a spider’s web, then where do I fit in? Maybe I’m the fly’ – offers a sense of foreboding.

The novel has a neat structure. Chapters are divided into two sections: the first is plot based and told by an invisible, omniscient, and third person narrator – conventional storytelling, with a few passages of interior monologue and direct speech. The narrator, Samson Young, takes the floor in the second section, which has a more meditative aspect. Entire sequences are retold, sometimes more than once, taking on the points of view of the different parties, or revisiting one thread of the story from varying viewpoints. This well organized structure mirrors a complex, web-like plot, a real stratification playing with time and points of view.

The effect of this constant adjustment of focus is heightened by frequent flash-forwards and pauses, introduced courtesy of the narrator. Most of these are false trails, as the reader will find out. The surprise, and role reversal, at the end brings you back to the prologue: ‘not a whodunit, more a whydoit’ – or rather it disavows this statement, and by doing so revives the murder story at the core of the book which had apparently been diminished, ridiculed and disregarded.

So London Fields, with totally disintegrated unity of time, elects end-of-century London – and more exactly Notting Hill – as a consistent unity of place.

London and its counterpart

The location of the novel is proclaimed in the prologue, as if a programme:

Then the city itself, London, as taut and meticulous as a cobweb. … It reeked of sleep. Somnopolis. It reeked of it, and of insomniac worry and disquiet, and thwarted escape.

London’s pub aura, that’s certainly intensified: the smoke and the builders’ sand and dust, the toilet tang, the streets like a terrible carpet. … I always felt I knew where England was heading. America was the one you wanted to watch…

The newly-arrived American writer represents the city with words that point to the senses – sight, smell, touch. It couldn’t be an inch more negative. London’s inadequacy is highlighted by comparison with its antagonist across the ocean, New York. The two worlds – the north European and the north American, the most advanced hubs of civilization – are contrasted dialectically, while no other geographical realities are considered save for vacations in Spain and in Venice (which play out as expensive and unhappy experiences for the characters).

The city of London, illumined by a strange light owing to an abnormal inclination of the Earth’s axis, menaced by mysterious ‘dead clouds’, and subject to mass evacuation measures, interacts in several ways with the plot and the characters. The storyline unfolds from a very precise spot, The Black Cross pub on Portobello Road, ‘on a day of thunder’ when, still unknown to each other, the male characters are drinking there:

If London’s a pub and you want the whole story, then where do you go? You go to a London pub. And that single instant in the Black Cross set the whole story in motion.

With her entrance, the female character and Murderee works quite literally as a catalyser, attracting in her orbit, and more precisely in the web she will patiently weave over the following months, the other main characters. Well into the novel, the narrator discloses he was there too, and relates how he was gradually welcomed into the pub’s small community. Of course, Keith Talent (‘The Murderer’) will play the role of a bizarre Virgil for the narrator – still unnamed, by the way.

The primary plot – the murder story proper – runs alongside at least three parallel sub-plots, which all have consequences for the three male characters. Such a web-like plot fits well with the urban setting. The female protagonist, however, has no secondary storylines – the numerous flash-backs apart – as this character is totally absorbed by the main storyline, which is literally her destiny. Indeed, she moulds her destiny: ‘We’re not all puppetmasters like you’, the narrator comments. As soon as Nicola Six – who is always aware what will befall her – enters the fatal pub, she knows she has finally met her murderer (‘I’ve found him. On the Portobello Road, in a place called the Black Cross, I found him’). She only has to induce him to do it, because ‘[t]he murderer was not yet a murderer’.

The author’s ability lies in having the reader believe that the victim knows who will be her murderer, without her ever coming clean about his identity. Indeed, the narrator orients the whole story to spread false trails and wrong assumptions. The real narrator, then, is Nicola.

Breaking all narrational codes and contradicting his own role as witness, the narrator seeks vengeance on the ‘Murderer’ and the ‘Foil’ and finish off his leading character, who has cooked the books once the book was written. The scene that has appeared throughout the novel is thus resolved:

The black cab will move away, unrecallably and for ever, its driver paid, and handsomely tipped, by the murderee. She will walk down the dead-end street. The heavy car will be waiting; its lights will come on as it lumbers towards her. It will stop, and idle, as the passenger door swings open.

His face will be barred in darkness, but she will see shattered glass on the passenger seat and the car-tool ready on his lap.

‘Get in.’

She will lean forward. ‘You,’ she will say, in intense recognition: ‘Always you.’

‘Get in.’

And in she’ll climb…

This passage, a flash-forward (note the future tense) rich in potentially misleading details, recurs in at least four other places in the novel, highlighting the sense of impending destiny. The scene is visually striking, bearing the traits of a noir film. Expectation is fuelled, because ‘his face will be barred in darkness’ until the actual ending, when the Murderer will have understood he’s the one at last, and the scene will be told, for the last time, in the first person and the past tense: ‘My face was barred in darkness’.

City, Love, Catastrophe

This intriguing plot is deeply rooted in the city, a dejected London set in the semi-future. An on-going global crisis is repeatedly mentioned, but no explanation or context is provided so its nature remains irritatingly obscure. We can only infer that it’s something to do with both politics and the weather. This emphasizes a sense of disintegration in the texture of the metropolis.

Changes in weather and time have led to local phenomena such as ‘people growing up and getting old in the space of a single week. Like the planet in the twentieth century, with its fantastic coup de vieux. Here, in the Black Cross, time was a tube train with the driver slumped heavy over the lever, flashing through station after station’, or ‘the recent convulsions … Particularly the winds. They tear through the city‘.

Amis offers another, distinctively British, example of decay:

There was no one in the telephone box. But there was no telephone in it either. There was no trace of a telephone in it. And there was no hint or vestige of a telephone in the next half-dozen he tried. These little glass ruins seemed only to serve as urinals … Vandalism had moved on to the human form. People now treated themselves like telephone boxes.

There’s mention of emergency measures: ‘Shepherds Bush cordoned off again…’; ‘Contingency plans. Partial evacuation of Central London’. These warnings come unannounced to the reader, as if a state of emergency were customary.

Besides these snapshots of the city, the sense of an impending catastrophe is conveyed by two principal images, rain and the so-called ‘dead clouds’. The former, ‘the unwholesome rain’, recurs constantly, as it will in many other works by different authors over the next two decades: ‘Ten o’clock, and it was dark outside. … Even the rain was dark’; ‘The rain made toadstools of the people on the street. … as the wet souls converged at the entrance to the underground, faceless stalks’ (an inevitable reference to T.S. Eliot); ‘The rain is terrible. It wouldn’t look so bad in a jungle or somewhere, coming like this, but in a northern city, suspended from soiled clouds. … These gusts of rain’; ‘diagonal arrow showers of reeking rain’; until –

[o]utside, the rain stopped falling. Over the gardens and the mansion-block rooftops, over the window boxes and TV aerials, over Nicola’s skylight and Keith’s dark tower (looming like a calipered leg dropped from heaven), the air gave an exhausted and chastened sigh. For a few seconds every protuberance of sill and eave steadily shed water like drooling teeth. There followed a chemical murmur from both street and soil as the ground added up the final millimetres of what it was being asked to absorb. Then a sodden hum of silence.

This beautiful view of the wet city offers a classic urban image, combined with a tense, foreboding vision.

Dead clouds, allegedly a by-product of the reckless exploitation of the Earth’s environment, loom over already worn-out cities. In London Fields, the narrator ‘saw a dead cloud not long ago. I mean right close … The dead cloud came and oozed and slurped itself against the window. God’s foul window rag. Its heart looked multicellular. I thought of fishing-nets under incomprehensible volumes of water, or the motes of a dead TV’. The objective gaze of a virtual camera watching London describes them as follows: ‘a dead cloud collapsing into the fog of dark rain’; ‘The weather has a new number, or better say a new angle. And I don’t mean the dead clouds. … The weather really shouldn’t be doing this’;

Shaped like a top-heavy and lopsided stingray … a dead cloud dropped out of the haze and made its way, with every appearance of effort, into the dark stadium of the west. … Dead clouds made you hate your father. Dead clouds made love hard.

From one image to the next, the author’s theory becomes clearer: in London Fields, objects and phenomena are always symbolic, and a crucial connection is established with the theme of the death of love.

There is one more symbolic form of the planet’s implosion, a less obvious but very loud one: the Nicola Six character. Not only does she significantly live in a dead-end street, but her sex preferences are expounded in a chapter where syllogisms and literary parallels are also drawn: ‘With her, light went the other way… The black hole weighed in at ten solar masses, but was no wider than London. … That’s what I am, she used to whisper to herself after sex. A black hole. Nothing can escape from me’.

If love in 1999 is no more – one of the novel’s alternate titles was to be The Death of Love – then sex turns into a black hole, an entropic, deadly process.

(Re)presentation of a city

By way of a set of literary devices and a wide-ranging vision including extensive use of the fourth dimension, the London of London Fields is far from a conventional representation of the city. Martin Amis shaped a London less virtual than you would have imagined in the 1980s.

With this novel, we see an apocalyptic city, possibly the best representation of the feelings and states of mind at the turn of the millennium. It is a city with a stratified, multi-directional texture that the reader can only access through a forever partial and ultimately treacherous perspective. In this ‘not a whodunit, more a whydoit’, the oppressive apocalyptic imagery is relieved by the comic quality of the social satire, which draws on Amis’s talent as observer and humorist. His city is deeply rooted in the existing topography but can be transfigured into a visionary metropolis – all through a very small but highly symbolic shift in time, from the 1980s to 1999. His powerfully sharp vision of London manages to pull the capital out of its narrow geo-political borders and creates a universal, post-contemporary metropolis.

Carla Scura, PhD, wrote the book Dove comincia il tempo. La Londra di fine millennio nel cinema e nella letteratura (‘”Where time begins”: London in film and literature at the end of the millennium’) NEU, Rome 2007 – it includes a longer version of this article.She is a media professional, translator, content curator, and producer.

References and Further Reading

Victoria N. Alexander, ‘Martin Amis: Between the Influences of Bellow and Nabokov’, The Antioch Review, Fall 1994

Martin Amis, The Moronic Inferno and Other Visits to America (New York: Viking Press, 1986)

James Diedrick, Understanding Martin Amis (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1995)

Brian Finney, ‘Narrative and Narrated Homicide in Martin Amis’s Other People and London Fields’, Critique, 37, 1995

Anne Friedberg, Window Shopping (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993)

Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993)

Dmitrij S. Lichacev, ‘Le proprietà dinamiche dell’ambiente nelle opere letterarie’, in J. Lotman and B. Uspenskij (eds), Ricerche semiotiche (Turin: Einaudi, 1973)

Elisabeth Mahoney, ‘The People in Parentheses’ in D. B. Clarke (ed.), The Cinematic City (London: Routledge, 1997)

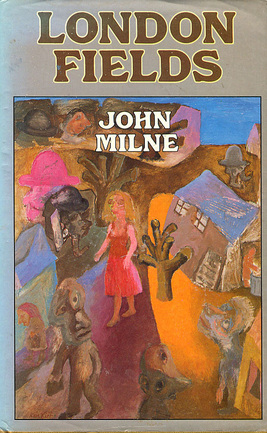

John Milne, London Fields (London: Heinemann, 1983)

Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses (London: Viking, 1988)

The ‘other’ London Fields

Ken Worpole writes about the original London Fields

When in 1988 Martin Amis and his publisher announced that his forthcoming novel was to be called London Fields, there were a few gasps of surprise and dismay, especially amongst aficionados of the London novel genre: a perfectly good novel of the same name was already in print. More than that, it was an intriguing novel of small-time criminals and families on the edge of things – and their mirrored counterparts in a corrupt police force – which had very distinctive things to say in its own right.

When in 1988 Martin Amis and his publisher announced that his forthcoming novel was to be called London Fields, there were a few gasps of surprise and dismay, especially amongst aficionados of the London novel genre: a perfectly good novel of the same name was already in print. More than that, it was an intriguing novel of small-time criminals and families on the edge of things – and their mirrored counterparts in a corrupt police force – which had very distinctive things to say in its own right.

Neverthless, Amis, his agent and his publisher apparently felt no problem in over-riding other people’s literary achievements for the sake of a good title.

John Milne’s London Fields was published in 1983, and is an accurate period piece portraying a young, likeable but disorganised chancer called Alfred Hicks – Elfie Icks as he terms himself – who unwittingly gets caught up in a territorial drugs war between rival white and black gangs, with the police throwing petrol on to the fire just to keep things moving along. Milne obviously knew a lot about police life and culture in the city, going on to write scripts for the TV series, The Bill. The slang, the patois, and the detail of pub life, club life and life down the station – and eventually inside prison – ring true.

What makes the novel more than just another programmatic lowlife fiction is the character of Elfie who, like Bill Naughton’s Alfie, or Alan Sillitoe’s angrily nonconformst ‘long distance runner’, dominates the narrative pace and style of the book. The novel is book-ended by opening and closing chapters which describe a prison psychiatrist trying to understand how Elfie got caught up in such a tangled mess which only ended with Elfie beating a villain to death in an underground station. The bizarre conversations between the trick cyclist – yes it’s that period of slang – and Elfie are funny, and strangely profound.

Milne’s book is actually a good examination of how slightly aimless, disorganised young men, who dream of better things, can drift by degrees from the street market to the hardcore underworld of gangland drug dealing, with the terrible results which eventually occur.

All rights to the text remain with the authors.