Nicolas Tredell

Lionel Asbo: State of England is set largely in a London of Martin Amis’s own making, a metropolis in the extreme mode, an excessive fantasy in which places and buildings stand for states of mind and become stages on which people play out dramas of destruction and desire. We may think we have been here before, in Amis’s earlier novels, especially his ‘London trilogy’, Money (1984), London Fields (1989) and The Information (1995). But there are differences which might be interpreted as signs of creative decline but could also evince a development in Amis’s perception and representation of the metropolis that has its own validity.

The novel tells two contrasting stories, in the jerky, jump-cut, zoom-in-and-out way typical of Amis’s narrative technique. One is the tale of its title character, a violent but unsuccessful criminal from infancy, who, on his eighteenth birthday, changed his surname from Pepperdine to Asbo, the acronym for ‘Antisocial Behaviour Order’, a measure inaugurated by the Crime and Disorder Act of 1998 to restrain perceived antisocial behaviour that did not actually constitute a criminal offence.

In 2009, while serving a prison term, Lionel learns he has won almost £140,000,000 in the National Lottery and becomes a focus of media attention, particularly after his release. Another violent affray soon puts him behind bars again; but he emerges later to pursue, very publicly, a relationship with Sue Ryan, a celebrity model and poetaster who styles herself, with inverted commas, ‘Threnody’ and who is renowned for her costly breast-job. This relationship comes to an end after ‘Threnody’ loses, or possibly aborts, their baby.

The contrasting tale is that of Lionel’s mixed-race ward and nephew Desmond Pepperdine, six years Lionel’s junior, who survives the absence of his father, the early death of his mother and an incestuous affair with his grandmother when he is fifteen, to obtain a degree, a wife, a baby daughter and a job as a Daily Mirror reporter.

In contrast to Guy Clinch, the good guy in London Fields who is no match for the very bad guy Keith Talent, Des does outwit Lionel in the end; but while endowed with occasional flashes of perception, he is an insipid, strangely desexualised figure, compared, for instance, to the Oxford-bound white youth Charles Highway in Amis’s first novel, The Rachel Papers (1974).

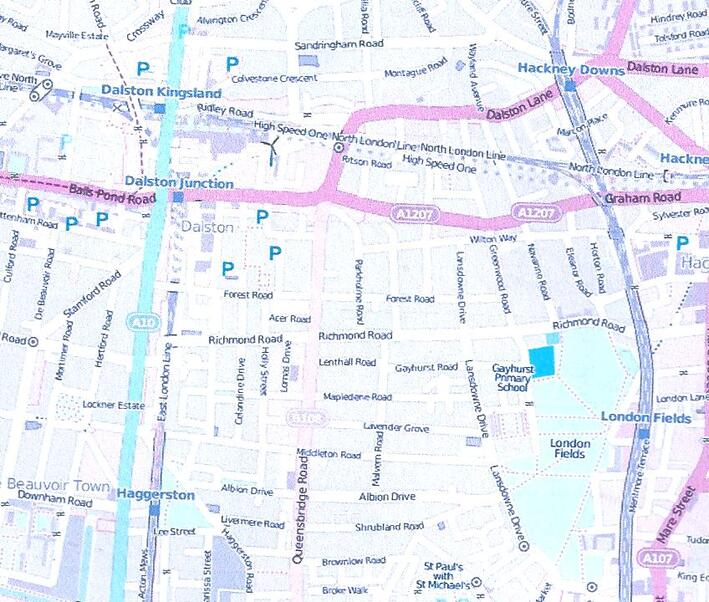

As Asbo’s subtitle suggests, the novel is a loose national allegory about the nefarious and nurturant forces in present-day England but its focus, as always with Amis’s Albion, is on the capital. There are four main London locations in the novel. One is the fictional borough of Diston, whose name is a partial echo of the real London district of Dalston. Like Dalston, Diston is adjacent to London Fields and, in an allusion that is both intertextual and topographical, the latter is named once in Asbo as the place from which the six black killers of a black teenager came: as Lionel puts it: ‘six London Fields boys come down here. They come down here to put theyselves about. And they go and top this fifteen-year-old’. We will hear more about this killing later in the novel.

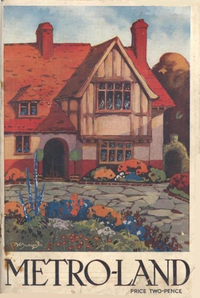

The second London location in Asbo consists of those suburbs to the northwest of London, built in the early twentieth century and accessible via the Metropolitan Railway from Baker Street, that were dubbed ‘Metroland’ by the railway’s marketing department in 1915 and later given iconic literary status by the poet John Betjeman in his verse and his 1973 TV documentary.

The third is the West End, seen as a place of hotels, clubs, pubs and brawls, while the fourth is that area of common land, the largest in London, known as Wormwood Scrubs.

Within the first and fourth of these locations, two buildings are especially important. One, in Diston, is Avalon Tower, where Lionel, his two psychopathic pitbull terriers, and Des, and later Des’s wife Dawn and their baby Cilla dwell at the top, on the thirty-third floor. The name ‘Avalon’ ironically references both Arthurian legend and New Age fantasy, but the tower is allowed a certain grandeur that does not wholly fall under the sign of irony; it is an ‘incredible edifice’, a ‘stacked immensity’, ‘the great citadel’, distantly recalling the ‘Cyclopean towers’ of 1920s New York apostrophized by the poet Hart Crane. But the vertiginous panoramas visible from high balconies that might seem one of the saving graces of tower blocks go unperceived; beyond the balcony of Lionel’s flat, there is only ‘the usual London sky. The white-van sky of London’.

The second important building is the one most people think of when they hear the name Wormwood Scrubs – not the common, but H.M. Prison Wormwood Scrubs, Lionel’s first and favourite gaol. When he buys a mansion in an Essex village, he renames it ‘Wormwood Scrubs’ and encloses it with tight security to keep the media out, thus recreating the urban prison in the rural landscape.

To further our mapping of Lionel’s London, we will explore, in turn, each of the four main London locations we have outlined.

Diston

‘To evoke the London borough of Diston’, as Amis grandly puts it, he summons an ancient source: ‘the poetry of Chaos’, in the shape of lines from near the start of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1:17-20), as rendered in English by Ted Hughes:

Each thing hostile

To every other thing: at every point

Hot fought cold, moist dry, soft hard, and the weightless

Resisted weight.

Much later in the novel, Amis reiterates, rewords and elaborates this, adding disruptive aural particularities – honking, yelling and swearing – to Ovid’s oppugnant opposites:

In Diston – in Diston, everything hated everything else, and everything else, in return, hated everything back. Everything soft hated everything hard, and vice versa, cold fought heat, heat fought cold, everything honked and yelled and swore at everything, and all was weightless, and all hated weight.

By calling this borough Diston rather than Dalston, Amis avoids locating it too firmly in the real world and is able to call on the classical, Renaissance and etymological resonances of its first syllable. Dis is a name for the ancient Roman god of the underworld, and for the lower circles of Hell in Dante’s Inferno. As a prefix expressing negation, it is also a homophone of another prefix, ‘dys’, meaning bad or difficult.

Diston is a dysfunctional dystopia, still retaining but ironizing the faint trace of the utopian aspirations of post-World War II planners and architects. It is a place of short lives and high fecundity: its inhabitants move from precocious pregnancy through decades of decay, ‘with its gravid primary-schoolers and toothless hoodies, its wheezing twenty-year-olds, arthritic thirty-year olds, crippled forty-year-olds, demented fifty-year olds, and non-existent sixty-year-olds’. Amis sets its demographic statistics in a global context:

On an international chart for life expectancy, Diston would appear between Benin and Djibouti (fifty-four for men and fifty-seven for women). And that wasn’t all. On an international chart for fertility rates, Diston would appear between Malawi and Yemen (six children per couple – or per single mother). Thus the age structure in Diston was strangely shaped. But still: Town would not be thinning out.

Despite the pro-natalism that features in the latter part of the novel, there is a touch of demographic anxiety here, a sense that Diston’s inhabitants, though their lives are nasty, brutish, poor and short, are nonetheless multiplying – and might inherit the earth. Their potential power is registered in Des’s ‘obstinate belief that Town contained hidden force of mind – nearly all of it trapped or cross-purposed. And how will it go, he often wondered, when all the brain-dead awaken? When all the Lionels decide to be intelligent? ….’

But bad dreams perturb the current sleep of the brain-dead. Diston is a place of ultra-violence; fights no longer take place with fists but with knives and guns, to the death. In this hostile environment, Des lives his life in metaphorical tunnels: one takes him from flat to school, another from school to flat, and a series of ‘warrens’ leads to his incestuous grandmother.

The borough contains only two significant public facilities. One is Squeers Free School, which has ‘the most police call-outs, the least GCSE passes’, ‘the highest truancy rates’ and the most ‘suspensions, expulsions, and PRU “offrolls”’ – transfers to a Pupil Referral Unit, which usually lead to a Youth Custody Centre and then to a ‘Yoi’ – Young Offender Institution. The other is the local Public Library, a remnant of a civic concern to make learning and literacy freely available to all. Both institutions, whatever their drawbacks, assist Des in his rise to the status of university student.

Pylons, the symbols of an ambiguous but monumental modernity for a school of 1930s poets, are now ‘low-rise’ rather than high in Diston and hotly sexualized rather than coolly statuesque (Stephen Spender’s ‘nude, giant girls that have no secret’). The local canal, once a feat of human engineering channelling natural forces, has turned into a salacious hot spring. A toxic energy issues from decaying domestic and digital detritus:

In Diston there were many thousands of pylons, and they all sizzled. The worst stretch of Cuttle Canal was as active as a geyser: it spat and splatted, blowing thick-lipped kisses to the hastening passers-by. Beyond Jupes Lanes sprawled Stung Meanchey (so christened by its inhabitants, who were Korean), a twelve-acre dump of house-high electronic waste, old computers, televisions, phones and fridges: lead, mercury, beryllium, aluminium. Diston hummed. Background radiation, background music for a half-life of fifty-five years.

Diston is an ecological catastrophe. The ‘natural surroundings’ consist of ‘[d]usty chestnuts, cloth-capped flowers, bent beer cans’, with ‘[o]nly the smell of liquid waste maintain[ing] the power to astonish – the way it maddened the gums’. The very air is abrasive, impedes vision, implies illness; it is ‘a mist of grit, the texture of gauze, with motes, blind spots, puckerings, like vaccination scars’.

If Diston’s ravaged ecosphere symbolizes the present, its street and place names summon the past since they mostly bear those of Dickens characters: Blimber Road, Carker Square, Cuttle Canal (Dombey and Son); Squeers Free School (Nicholas Nickleby); Jupes Lanes (Hard Times); Doyce Grove (Little Dorrit); Murdstone Road (David Copperfield). A phantom Dickensian topography thus hovers behind the London of Asbo, although the Dickens novels to which it is most nearly allied in terms of its unremitting focus on urban degradation are not those to which these names allude, but Bleak House and Our Mutual Friend.

The closest Asbo comes to a Dickensian good place is the flat atop the Avalon Tower when Des and Dawn and their baby, Cilla are together there – and the fragility of this is sharply shown when Cilla only escapes from being savaged by Lionel’s dogs, when she is accidentally pitched into a ‘cuboid gunmetal rubbish bin’ whose open lid then snaps shut.

As well as recalling Dickens’s darker visions of the capital, Amis’s London also echoes, though not through explicit verbal references, the more negative visions of William Blake, both in the poem ‘London’ and in those parts of the Prophetic Books that anatomize arrests of life. But in Asbo, Amis cannot summon up sufficiently strong ‘Songs of Innocence’ to counterbalance his ‘Songs of Experience’; Cilla, the embodiment of innocence, is largely an object of possessive paternal voyeurism; Amis never tries to look out of a child’s eyes.

Asbo also largely evades the issue of the ethnic composition of Diston that is inevitably raised by Amis’s choice of a mixed-race character as his main counterweight to Lionel. As a schoolboy, Des is a prime target for playground persecution but escapes it because he is known to be under the protection of Lionel. But according to Amis, he is a prime target because of his regular attendance, his attentiveness in class, his eschewal of drugs, his preference for the company of girls rather than that of boys; his misfit status that links him with other misfits, ‘swats [sic], wimps, four-eyes, sweating fatties’. One other element, however, that might make him a potential object of persecution – his mixed race – is omitted.

Lethal violence towards a black youth has struck in Diston. An account of Dawn and Des on a Sunday stroll makes this clear:

Their pace slowed as they approached the little memorial to Dashiel Young. Dashiel, the Jamaican teenager beaten to death by six grown men on Steep Slope – six years ago. A lozenge of grey stone, indented, flush with the ground, and the etched words: Always Remembered. Dashiel Young, 1991-2006. Des bowed his head. He always remembered. Grief is the price we pay for … They moved on.

The tone is uncertain here; the passage could easily come across as a parody of Des’s piety, even more so when we realize Amis’s play with the reader’s assumptions. We may at first think this was a racist murder, a white gang killing a black teenager, but it was in fact a black-on-black crime committed by the six black men from London Fields whom Lionel had mentioned 130 pages earlier in the novel. Amis does not remind us of this here, but once we make the link it reinforces the sense that the novel seeks to play down racial violence and emphasize, more broadly, violence, as an ever-present feature of urban, and perhaps human, life.

Although Dawn’s relationship with Des estranges her from her racist father until he is on his deathbed, this receives fairly perfunctory treatment. When, immediately after the birth of her daughter, Dawn broaches the question of the new arrival’s skin colour, she uses a coy metaphor – ‘She takes a little bit more milk in her coffee than you do, doesn’t she Des?’ – which she later repeats, as if for emphasis. The mixed-race issue is lightly embodied in Des but not pursued in its implications for him personally or for the novel’s representation of London.

In this respect, Amis’s portrayal of a multi-ethnic metropolis has too much milk in it, whitening out the awkward questions that his focus on a mixed-race character necessarily raises.

Metroland

On the way to the ‘Whitsun wedding’ of Lionel’s friend Marlon Welkway to Gina Drago, Des and Dawn experience a suburban epiphany

Suddenly the train unsheathed itself from the black tunnel and soared out into the light of the May noon. And the weather – the air – was so fresh and bright, so swift and busy. Dawn said,

‘Look, Des.’ She meant Metroland. The orderly villas, the innocent back gardens, all aflutter in the swerving wind. ‘I once came this way at night,’ she said. ‘And you look and you think, Every [sic] light out there stands for something. A hope. An ambition …’

As so often in the descriptions of Des and Dawn, the tone is uncertain. It might perhaps be seen as an attempt to validate Metroland as an object of aspiration, to offer a bracing suburban updating of Wordsworth, with villas and back gardens ‘all aflutter in the swerving wind’ rather than daffodils fluttering and dancing in the breeze. But elements of the style – ‘so fresh and bright, so swift and busy’ – make it sound like parody, and Dawn’s dialogue, here as elsewhere, has the ring of a form of language on which Amis once declared war: cliché.

The journey into Metroland is also a journey into literary territory, that of John Betjeman and, with conscious homage to Betjeman, of Julian Barnes in his first novel Metroland (1980), which evokes but undercuts Betjeman, presenting Metroland as the place from which clever middle-class white boys seek escape but which may finally suck them back.

The allusion to Larkin in the mention of a ‘Whitsun wedding’ may also recall the patronising element in that poem, in which the solitary traveller, on a train bound for London, looks down on (even as he partly envies) the wedding parties, of an inferior social class, who gather at each station. So the passage tends to reinforce a familiar attitude of disdain towards suburbia even if it suggests why some people might desire the kind of life it seems to represent.

West End and Wormwood Scrubs

After winning the lottery and being released from prison, Lionel’s sphere of activity briefly becomes the West End before he is rearrested. Des and Dawn follow his itinerary in the tabloid press and the Daily Telegraph. The pattern is unvaried: ‘fights, expenditures, admissions, ejections’, a kind of tightly compressed version of an eighteenth-century picaresque novel.

Thrown out of his luxury hotel, the Pantheon Grand, Lionel checks into the Castle on the Arch; gets embroiled in a brawl in the Happy Man pub in Leicester Square; spends £1,900 on a lunch for himself in La Cage d’Or restaurant, Dover Street; provisionally joins, in quick succession, the Sunset Strip Lounge in Old Compton Street, the Soho Sporting Club (where he is said to lose massively at craps and blackjack) and the Taboo in Garrick Street.

He then gets thrown out of the Castle on the Arch; checks into the Launceston in Berkeley Square; gets into a short fight in the Surprise pub in Shepherd Market; orders a Bentley Aurora, costing £377,990, at the Piers Edwards Showrooms on Park Lane; gets kicked out of the Launceston; and finally finds refuge in the South Central Hotel, ‘the asymmetric ninety-suite high-rise that loomed like a whimsical robot over the stubby bohemia of north Pimlico’ and that specializes in accommodating troublesome celebrities, boasting of ‘Zero Ejections’.

When Lionel leaves an exclusive fish restaurant after a tussle with a boiled lobster that leaves him cut, bleeding and bad-tempered, he assaults three newspaper reporters and a policeman and is jailed once more for six years – again in his alma mater, Wormwood Scrubs: ‘the desolate rain-steeped stronghold that presided over a huge stretch of common land (brush and stunted forest growth) in Hammersmith, west London’.

Between the hotels, restaurants and clubs that cater to wealth, the public houses that become boxing rings without ropes or referees, and the vast tract of scrubby common land commanded by a prison, there is little in the way of congenial public or private space in Amis’s metropolitan vision.

Conclusion

The London of Lionel Asbo is a diminished metropolis, reduced to what the novel offers as its essential components: the chaos of Diston; the clichés of Metroland; the consumerism of the West End; the confinement of Wormwood Scrubs. This may seem an impoverished picture, in contrast not only to the Londons of other novelists but also to the capital of Amis’s own earlier novels. It might seem tempting to attribute such a picture to Amis’s own growing estrangement from London, and to England in general, which was confirmed by his move to the USA in 2011.

But if distance lends disenchantment to the view for Amis, it does not necessarily decrease, may even sharpen, his perspicacity. It could be argued that, just as he caught the Zeitgeist in Money, so he does, even from afar, in Asbo – but it is a different Zeitgeist, chastened by economic crisis, by an unevenly imposed austerity, by a more deeply commodified privacy and by an increasingly vestigial public domain. In such times, a vision of London that cuts out confidence in the future, except in the fragile form of babies, may be salutary: in this novel, Amis offers us, not London Fields with its trace, however ironic, of pastoral, but London peeled, stripped bare, shorn of its skin of illusions.

Nicolas Tredell is a freelance writer whose publications include books and essays on authors from Shakespeare to Martin Amis. He is the editor of The Fiction of Martin Amis, published by Palgrave Macmillan. He formerly taught literature and film at Sussex University. He is most grateful to Susie Thomas for first indicating to him the link between Diston and Dalston.

References and Further Reading

Martin Amis, Lionel Asbo: State of England (London: Jonathan Cape, 2012)

Brian Finney, Martin Amis (London and New York: Routledge, 2008)

Sebastian Groes, The Making of London: London in Contemporary Literature (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), especially chapter 7, ‘“In a Prose so Diagonal and Mood-Warped”: Martin Amis’s Scatological London’, pp. 167-90

Nicolas Tredell (ed.), The Fiction of Martin Amis (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000)

Nicolas Tredell, Literary Encyclopedia entries on The Rachel Papers; Dead Babies; Success; Other People; Money; London Fields; The Information; Heavy Water; Yellow Dog; The Pregnant Widow; Lionel Asbo. See http://www.litencyc.com/ (subscription required)

All rights to the text remain with the author.